20th Century & Contemporary Art Evening Sale in Association with Poly Auction

Hong Kong Auction 8 June 2021

1

Salman Toor

Girl with Driver

Estimate HK$1,200,000 - 2,200,000

Sold for HK$6,905,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

2

Emily Mae Smith

Broom Life

Estimate HK$400,000 - 600,000

Sold for HK$12,350,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

3

Loie Hollowell

First Contact

Estimate HK$1,200,000 - 1,800,000

Sold for HK$10,898,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

4

Tschabalala Self

KLK

Estimate HK$1,500,000 - 2,500,000

Sold for HK$3,150,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

5

Amoako Boafo

Gaze I

Estimate HK$600,000 - 800,000

Sold for HK$2,772,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

6

Joel Mesler

Untitled (Tony Chang Goes to Hollywood)

Estimate HK$400,000 - 600,000

Sold for HK$1,638,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

7

Jadé Fadojutimi

Concealment: An essential generated by the lack of shade

Estimate HK$600,000 - 800,000

Sold for HK$5,670,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

8

Kudzanai-Violet Hwami

The Egg

Estimate HK$800,000 - 1,200,000

Sold for HK$1,764,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

9

This lot is no longer available.

10

Matthew Wong

Figure in a Night Landscape

Estimate HK$6,000,000 - 8,000,000

Sold for HK$36,550,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

11

Bernard Frize

Toky

Estimate HK$1,000,000 - 1,500,000

Sold for HK$2,646,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

12

Lucas Arruda

Untitled from the series Deserto-Modelo

Estimate HK$1,000,000 - 1,500,000

Sold for HK$3,213,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

13

Gerhard Richter

Abstraktes Bild (940-7)

Estimate HK$75,000,000 - 95,000,000

Sold for HK$95,100,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

14

Park Seo-Bo

Ecriture No. 15

Estimate HK$4,000,000 - 6,000,000

Sold for HK$8,115,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

15

Zhou Chunya

Peach Blossom

Estimate HK$3,800,000 - 5,800,000

Sold for HK$7,268,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

16

Zhang Xiaogang

Family Portrait No. 13

Estimate HK$8,000,000 - 12,000,000

Sold for HK$10,535,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

17

Yoshitomo Nara

Missing in Action

Estimate On Request

Sold for HK$123,725,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

18

Yoshitomo Nara

Missing in Action 2

Estimate HK$2,500,000 - 3,500,000

Sold for HK$7,026,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

19

Yoshitomo Nara

Shallow Puddles Part 2

Estimate HK$4,800,000 - 6,500,000

Sold for HK$9,325,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

20

Martin Wong

Son of Sam Sleeps

Estimate HK$2,000,000 - 3,000,000

Sold for HK$2,772,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

21

Theaster Gates

Dirty Red

Estimate HK$4,600,000 - 6,200,000

Sold for HK$5,922,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

22

Banksy

Laugh Now Panel A

Estimate HK$22,000,000 - 32,000,000

Sold for HK$24,450,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

23

Andy Warhol

Dollar Sign

Estimate HK$3,500,000 - 5,500,000

Sold for HK$6,542,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

24

Ed Ruscha

1981 - Future

Estimate HK$4,000,000 - 6,000,000

Sold for HK$4,410,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

25

Yayoi Kusama

Nets Obsession

Estimate HK$10,000,000 - 15,000,000

Sold for HK$25,660,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

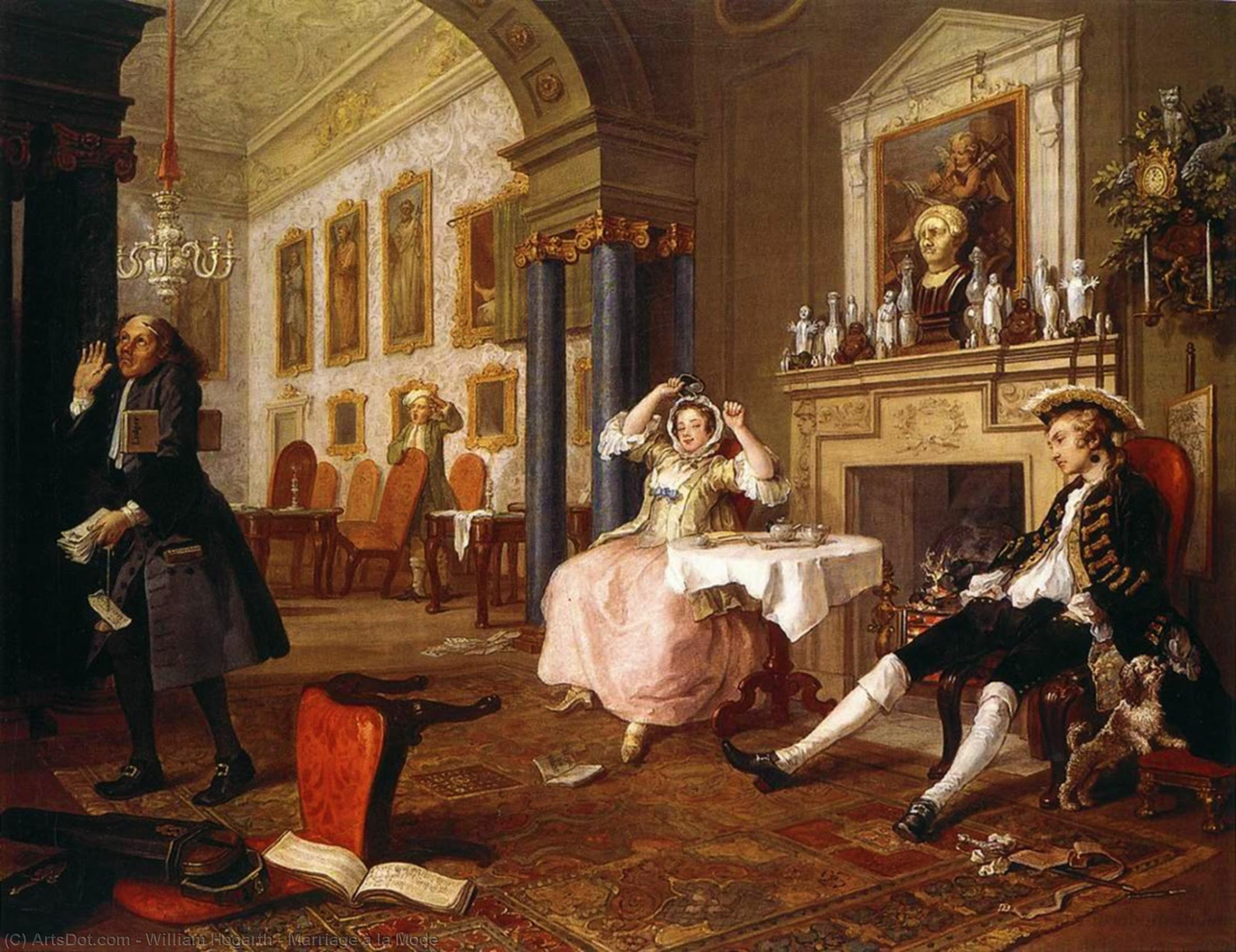

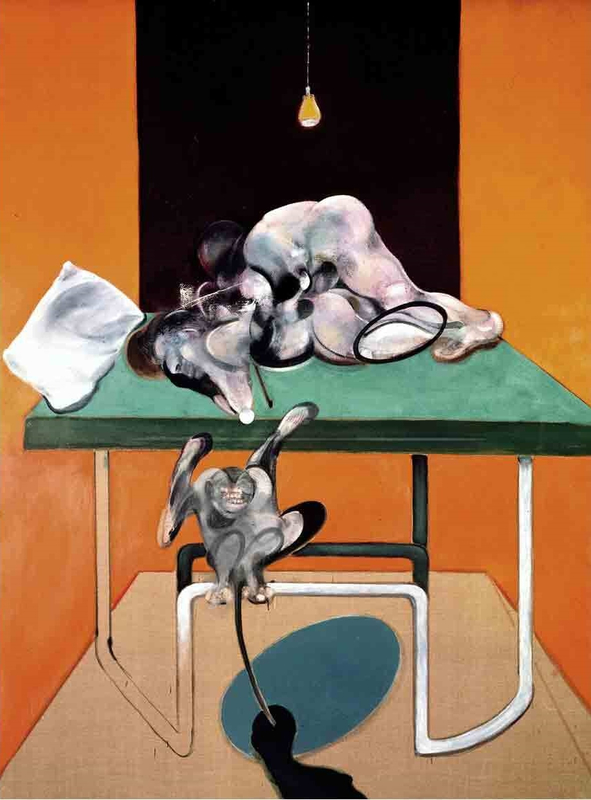

26

Cecily Brown

The End

Estimate HK$4,500,000 - 6,000,000

Sold for HK$8,599,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

27

Eddie Martinez

Christmas in July

Estimate HK$3,500,000 - 4,500,000

Sold for HK$5,922,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

28

George Condo

Sketches of Jean Louis

Estimate HK$10,000,000 - 15,000,000

Sold for HK$13,560,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

29

Pablo Picasso

Nu couché et musicien

Estimate HK$9,000,000 - 14,000,000

Sold for HK$11,745,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

30

This lot is no longer available.

31

Chu Teh-Chun

Nuances de l'aube

Estimate HK$2,800,000 - 3,800,000

Sold for HK$5,670,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

32

Hans Hartung

T1989-U40

Estimate HK$2,000,000 - 3,000,000

Sold for HK$4,284,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

33

Liu Wei

Purple Air 5

Estimate HK$1,200,000 - 2,200,000

Sold for HK$1,764,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

34

KAWS

TOGETHER

Estimate HK$7,000,000 - 9,000,000

Sold for HK$10,656,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

35

Andy Warhol

Lifesavers

Estimate HK$3,000,000 - 4,000,000

Sold for HK$6,174,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

36

Jordan Wolfson

Untitled

Estimate HK$800,000 - 1,200,000

Sold for HK$2,016,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

37

Kohei Nawa

PixCell-Deer #40

Estimate HK$1,400,000 - 2,800,000

Sold for HK$3,024,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.