Nature has found a spectacular number of ways to make things explode, and we call the most powerful of those explosions the supernovae.

Astronomers Walter Baade and Fritz Zwicky invented the name, itself, to describe the remnants of neutron stars in 1933. Prior to that, astronomers called any old exploding thing in the sky a “nova,” which is Latin for “new.” But once we began to understand that there were different kinds of explosions, flashes, and flares, we had to create an entirely new category to label the brightest one.

Waking Giants

There are two main categories of supernovae explosions, with completely different setups and mechanisms driving each. The first kind are known as “Type-II” or “core-collapse” supernovae, and they happen when giant stars finally reach the ends of their lives.

Every single star in the universe fuses elements in its core during its lifetime. This holds true from the smallest stars, which are barely larger than one-tenth the mass of the sun, to the giants that outweigh 100 suns. And every single star spends the majority of its life fusing hydrogen into helium.

✅ Why Stars Fuse Hydrogen Into Helium

–Hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe, and so there’s plenty to go around

–Fusing hydrogen releases the most amount of energy, so it’s the easiest fuel to burn

✅ Why Fusion Releases Energy

When hydrogen fuses into helium, the resulting helium atoms have a little bit less mass than the total mass of all the hydrogen atoms that formed them. Through Einstein’s famous E = mc2 equation—energy equals mass times the square of the speed of light—that difference in mass results in a release of energy.

Due to their small masses, these stars will sip away at their hydrogen reserves for trillions of years; stars like our sun, meanwhile, can last around 10 billion years before entering their final cycles, expanding into red giants. But the biggest ones—with their immense gravitational weight crushing their cores to extraordinary pressures—will rip through their hydrogen in only a few million years.

Once a giant star uses up its hydrogen, it begins fusing helium. And after that, it will fuse helium into carbon and oxygen. And after that, silicon and magnesium. Eventually, it will start to build up a solid ball of nickel and iron in its core.

And that’s when things start to get out of control.

Furious Endings

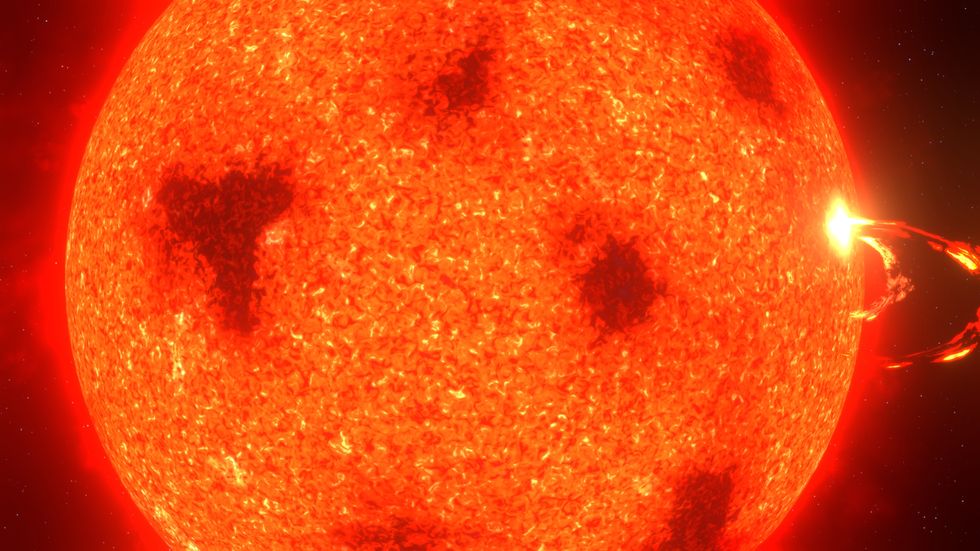

Right before the moment of its death, a giant star is an inflated, grotesque creature. Usually the outermost layers of its atmosphere will have detached from the star completely. The inside of the star is like a furious onion, with the iron core surrounded by layers of progressively lighter elements.

Each stage in a giant star’s life is shorter than the last. As the star ages, it fuses heavier and heavier elements in its core. And as the elements increase in mass, the energy released from fusion gets smaller. However, the star’s own weight never stops crushing inward, and so the fusion rates ramp up at an increasingly frenetic pace. A giant star will spend millions of years quietly burning through its hydrogen, and less than a million fusing helium. It can sustain carbon fusion for a mere 1,000 years. The production of iron in its core, the very last step before it goes supernova, lasts all of 15 minutes. All giant stars—from about eight solar masses to 200 solar masses, go through this same process.

The problem with iron is that fusing it doesn’t produce any energy. Instead, it takes energy to fuse iron into heavier elements, because atoms heavier than iron just aren’t bound together very tightly, so it’s extremely difficult to smush them together. The rest of the star continues to crush in on its core, but there’s no release of energy from the fusion to balance it out. The crushing just keeps happening.

The entire weight of the star bears down on the core, triggering a radical transformation. The core becomes so intensely squeezed that the iron atoms rearrange themselves; the electrons shove inside of protons, turning all of the iron into a giant ball of neutrons.

That giant ball of neutrons is—briefly—able to resist the collapse of the star around it through an exotic quantum process known as “degeneracy pressure.” Essentially, the neutron ball can’t be compressed any further without an overwhelming amount of force. And so all of the surrounding star stuff slams into the neutron ball and bounces back, triggering the beginning of a supernova explosion.

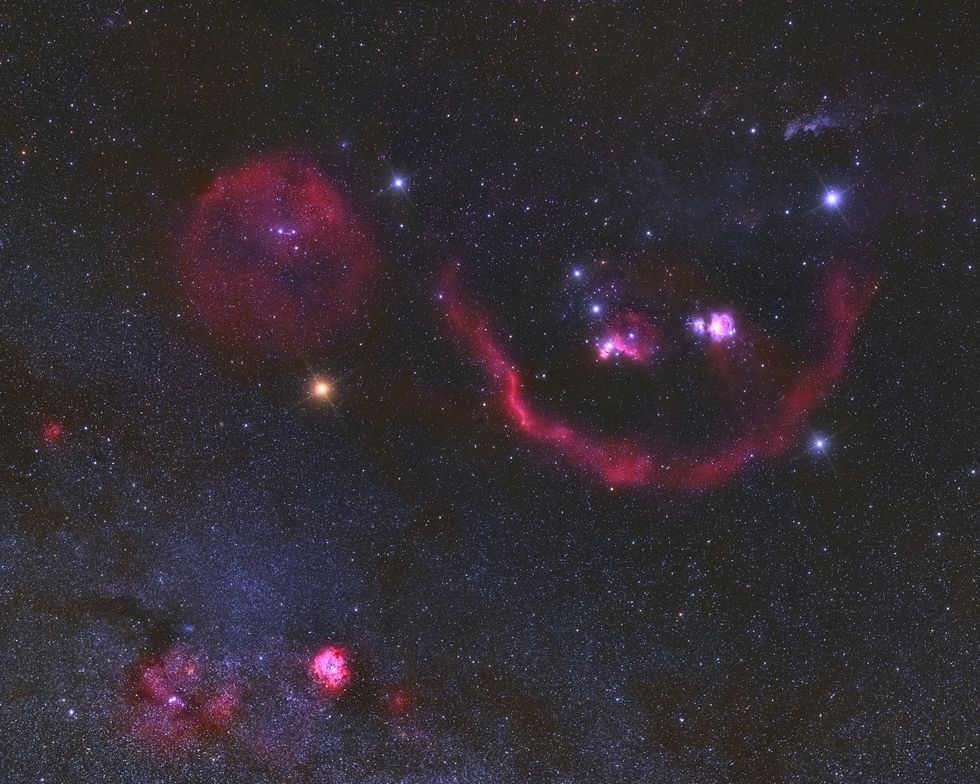

In less than a second, the entire star turns itself inside out, sending out a shockwave of its own material, racing away at nearly the speed of light. The burst of radiation that accompanies the explosion carries away an absurd amount of energy. To give you a sense of scale, the star Betelgeuse sits almost 650 light years away; it will go supernova sometime in the next million years. When it does, it will be bright enough to be seen during the day, outshining the full moon, and its light will be so intense that it will cast shadows at night.

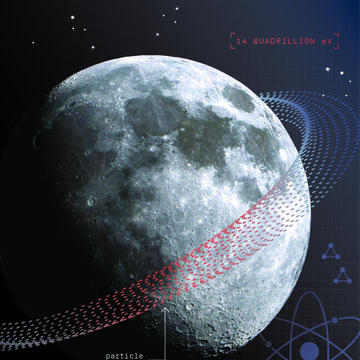

It’s fortunate Earth isn’t near a giant star with a heaving, unstable outer atmosphere, because there’s no way we’d be able to escape. The radiation and particles emitted from a core-collapse supernova will simply, and easily, rip you to shreds if you’re within 100 light years away.

Evil Twins

The other kind of supernova, known as Type-1a, is just as deadly.

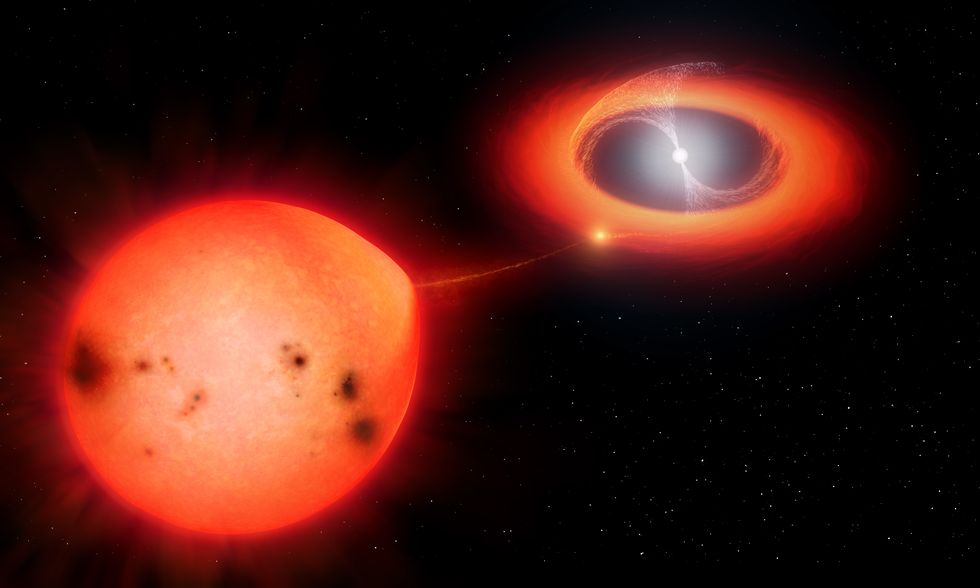

The Type-1a supernovae don’t come from solitary stars sitting around waiting to die, but from a case of pure stellar fratricide. Most stars in the universe are members of a pair; when giant gas clouds collapse to form stars, they tend to form a lot of them. And members of a binary system will never have the exact same mass; in fact, they often have wildly different masses.

With their different masses, they will go through their lives at different rates, with the heavier of the twins dying first. If that star is around the mass of the sun, then it will leave behind a white dwarf, a dense core of unfused carbon and oxygen.

Sometime later, its twin will reach the stage of its own lifecycle where it swells to become a red giant. When that happens, some of its own atmosphere will spill onto the surface of its now-dead white-dwarf sibling.

When the densities of that atmosphere reach a critical threshold, they can flash in a burst of hydrogen fusion, releasing a type of flare called a (regular) nova.

Annihilation

But when the conditions are just right, the red-giant companion can keep pouring and pouring its own atmosphere onto the surface of the white dwarf without interruption, the pressures and temperatures slowly ratcheting up.

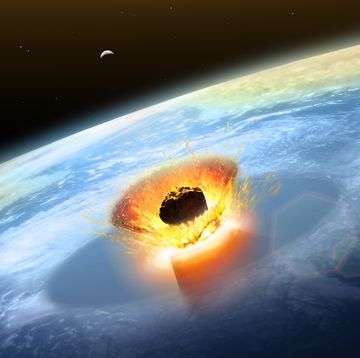

Eventually, it’s too much. The thick hydrogen atmosphere ignites in a single flash of fusion, releasing its pent-up energies at once. The explosion rocks the white dwarf, forcing the carbon and oxygen itself to undergo catastrophic, uncontrolled nuclear fusion.

It’s the largest atomic bomb in the universe—a single object, the size of Earth, but with enough mass to outweigh the sun, converting its entire mass in a nuclear fireball.

When these supernovae go off, they can outshine an entire galaxy. Keep in mind that galaxies typically host a few hundred billion stars. The show doesn’t last forever, though. Within a few weeks, the fury fades and the intensity subsides, leaving nothing but scattered remnants of the system drifting off into interstellar space.

Every galaxy like our own Milky Way produces a handful of supernovae every century, with about one-third of them being the Type 1a variety. The last visible one occurred in 1604, which generally freaked out astronomers around the world. If one were to happen too close to us, the resulting radiation blast and shockwave would obliterate our atmosphere.

Thankfully, no known stars in our nearby patch of the galaxy pose a hazard to us; even if any of them were to go supernova tomorrow, they would merely put on a pretty light show.

Paul M. Sutter is a science educator and a theoretical cosmologist at the Institute for Advanced Computational Science at Stony Brook University and the author of How to Die in Space: A Journey Through Dangerous Astrophysical Phenomena and Your Place in the Universe: Understanding Our Big, Messy Existence. Sutter is also the host of various science programs, and he’s on social media. Check out his Ask a Spaceman podcast and his YouTube page.