What Was Hygiene Like For Factory Workers During The Industrial Revolution?

One Writer Likened The Air Quality To Swallowing A Pound Of Cayenne Pepper

Photo: Quadell / Wikimedia Commons / Public DomainGerman writer Georg Weerth describes a terrifying scene for Englanders in 1846:

In Manchester the air lies like lead upon you; in Birmingham it is just as if you were sitting with your nose in a stove pipe; in Leeds you have to cough with the dust and the stink as if you had swallowed a pound of Cayenne pepper in one go - but you can put up with all that. In Bradford, however, you think you have been lodged with the devil incarnate. If anyone wants to feel how a poor sinner is tormented in Purgatory, let him travel to Bradford.

Weerth lived in Bradford, a major factory town during the Industrial Revolution, for three years. He shared his feelings of disgust over the living conditions for local workers with fellow revolutionary thinkers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. At the time, the average lifespan in Bradford was only 25 to 30 years because of the smoke.

While factory owners and residents of higher classes could flee the pollution in the city, laborers did not have the financial resources for such mobility.

Many Laborers Succumbed To Disease In Their Mid-20s

Today, the average life expectancy of a UK resident is 79 years for men and almost 83 years for women. During the Industrial Revolution, English factory workers were lucky to make it to 30.

While their middle-class counterparts usually lived to 45, laborers were exposed to disease and toxins at higher rates. Disease spread from person to person and from water sources to people. Rates of infection were worst in overpopulated cities and slums.

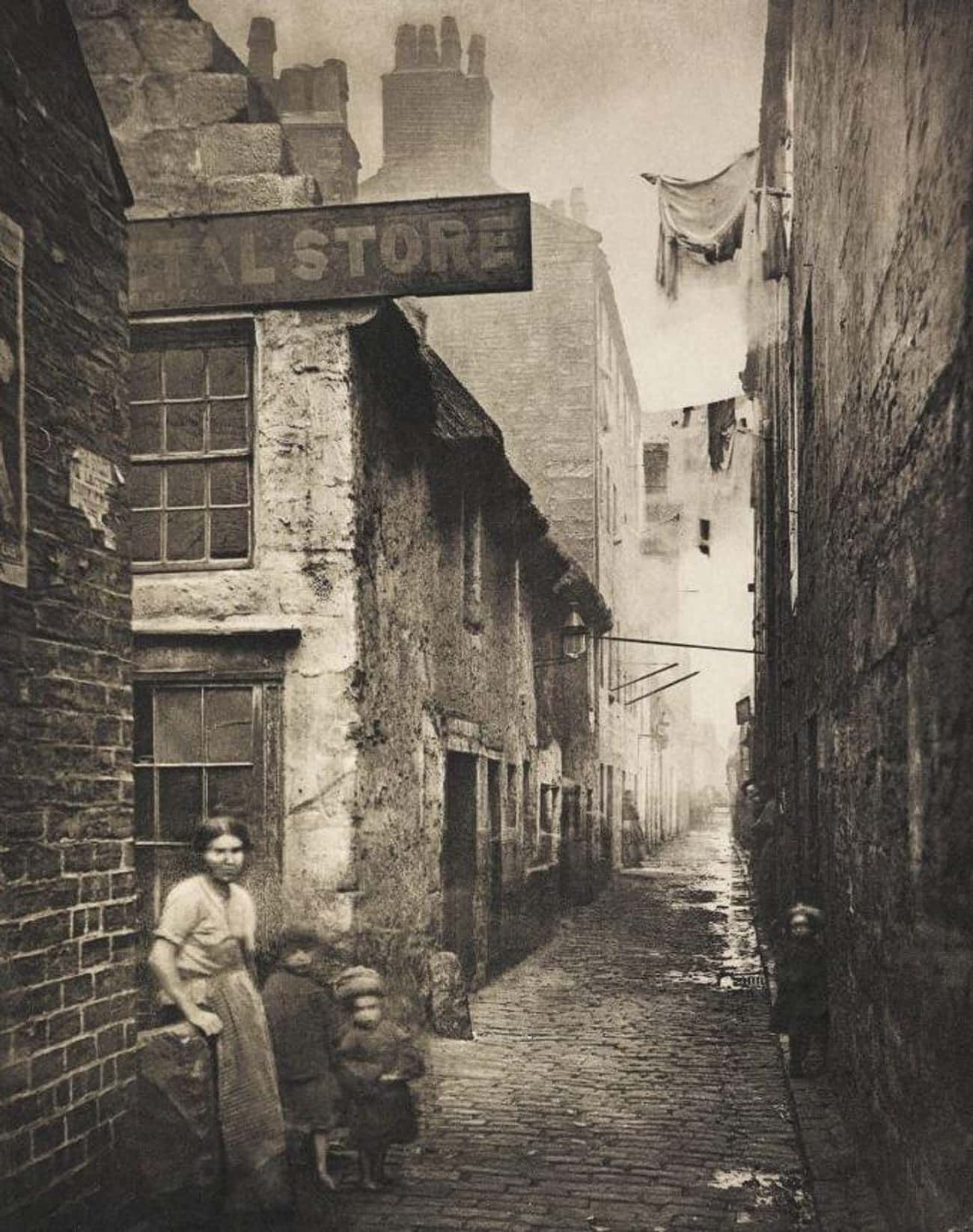

One Sanitary Report Described The Appearance Of The Impoverished As ‘Wretched And Neglected’

Photo: Thomas Annan / Wikimedia Commons / Public DomainReformer Edwin Chadwick, a British sanitation advocate, released a report in 1842 entitled Report on the Sanitary Conditions of the Labouring Population of Great Britain. In it, Chadwick lays out the squalor, filth, and foul circumstances most working class people were exposed to at the time. As he writes about what he sees in one town:

The cottages in the neighbourhood were of the most wretched kind, mere hovels, built of rough stones and covered with ragged thatch. The wife’s face was dirty, and her tangled hair hung over her eyes. Her cap was ill washed and slovenly put on. Her whole dress was very untidy, and looked dirty and slatternly; everything about her seemed wretched and neglected and she seemed very discontented.

Chadwick also showed the relationship between these living conditions and the spread of infectious diseases within these communities. Unfortunately, these places continued to be breeding grounds for diseases and their transmission.

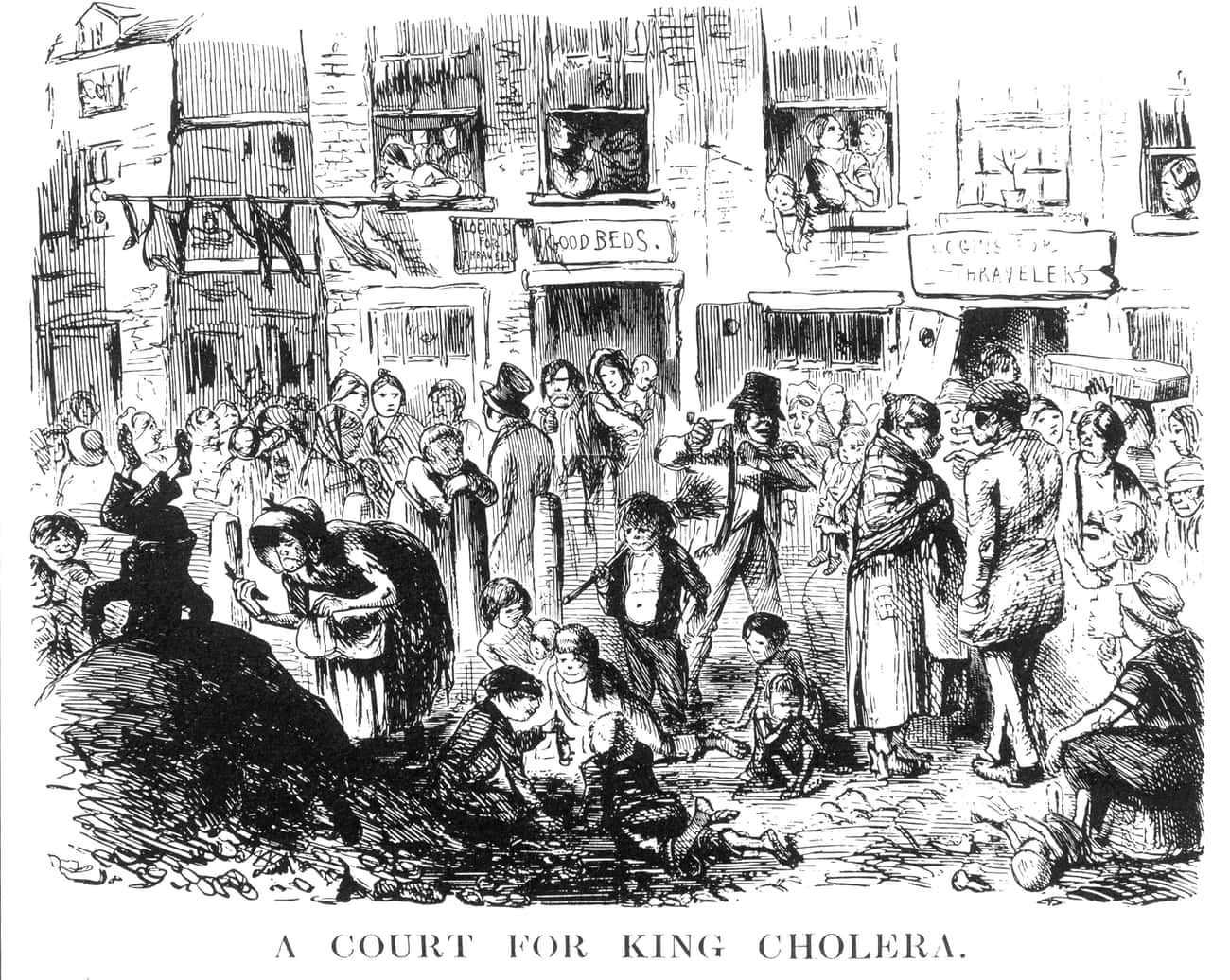

Cholera, Typhoid, And Typhus Were Rampant Due To Lack Of Public Sanitation

Photo: Punch Magazine / Wikimedia Commons / Public DomainThere were well-documented epidemics of cholera, typhoid, and typhus that affected the most vulnerable populations in industrial Britain.

During the 19th century, there were four cholera outbreaks in England. A bacterial infection, cholera causes severe gastrointestinal issues and dehydration that often takes lives. The disease originally came to Europe from the Indian subcontinent. It spread easily due to the lack of infrastructure to separate sewage water from drinking water. It developed the nickname "King Cholera" because of how many people it infected. In the 1848-1849 outbreak, roughly 15,000 people perished in London.

Typhoid and typhus were another pair of detrimental diseases that plagued industrial England. At the time, typhoid thrived in water sources, particularly wells, and caused flu-like symptoms. Typhus was found in lice, which were prevalent in crowded tenements and shared living spaces.

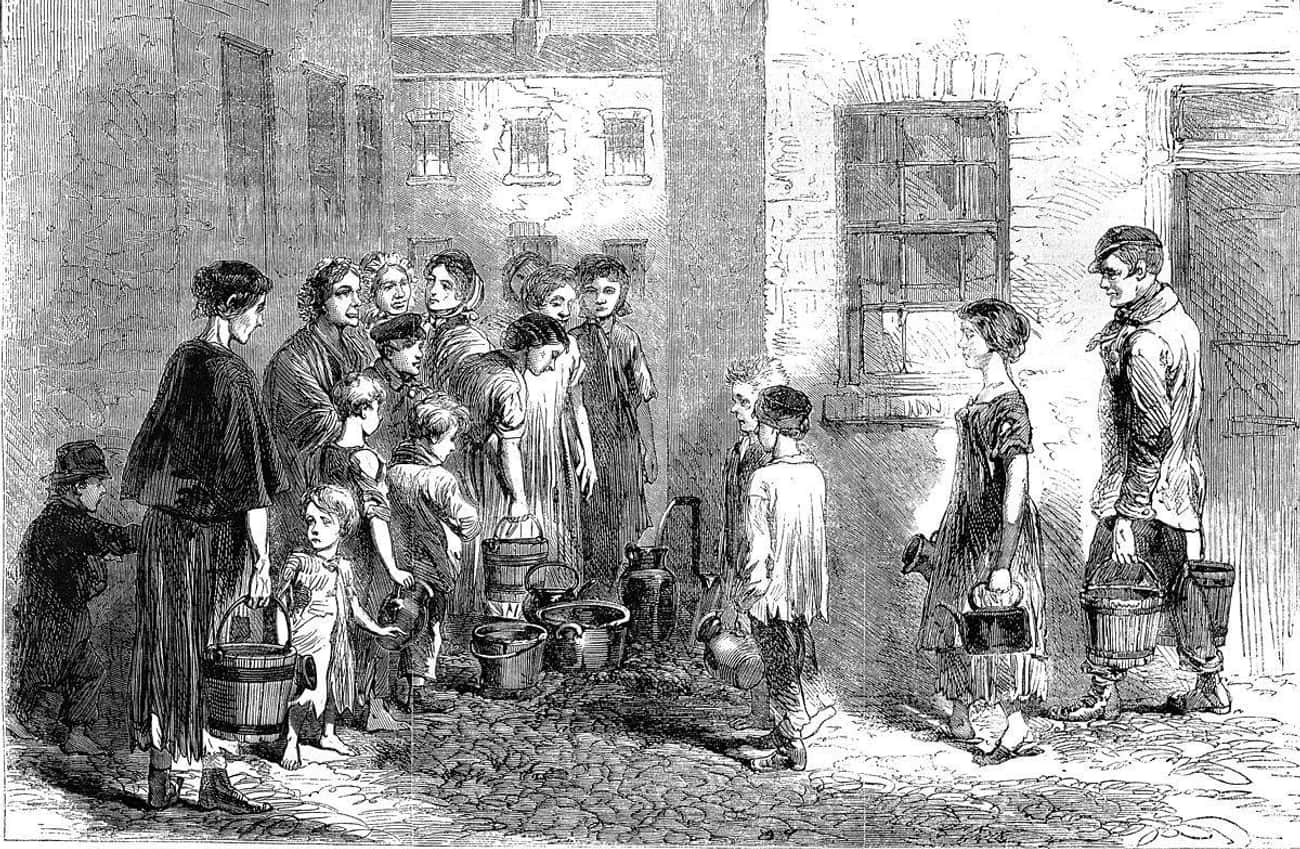

The Only Available Water Sources Were Heavily Contaminated

Photo: Unknown / Wellcome Collection / CC BY 4.0During and after the Industrial Revolution, most drinking water in England came from rivers. Since sewage and trash were often dumped into rivers, they became cesspools for disease. Residents drew their daily water from pumps connected to these polluted rivers.

In 1854, Dr. John Snow tracked down a pump in London responsible for a particularly devastating outbreak of cholera. Five-hundred people perished in just 10 days. In a letter, Dr. Snow explains how he isolated the pump as the source:

On proceeding to the spot, I found that nearly all the [mortalities] had taken place within a short distance of the [Broad Street] pump. There were only ten... in houses situated decidedly nearer to another street-pump. In five of these cases the families of the deceased persons informed me that they always sent to the pump in Broad Street, as they preferred the water to that of the pumps which were nearer.

Human Waste Was Discarded In The Streets

Photo: William Hogarth / British Library / Public DomainEnglish cities were built around factories, and space was limited. Housing complexes were built on top of each other and lacked many present-day amenities that now come standard with any housing situation. Without modern plumbing or latrines, workers in these cities dumped their waste into the city streets.

Alternatively, many buildings contained underground cesspools where waste would collect. Their contents often overflowed and found their way onto the streets as well. Since it had not been scientifically proven that harmful bacteria exist in excrement, these practices were normal throughout the Industrial Revolution.

The First British Public Health Act Was Not Passed Until 1848

Photo: Unknown / Wikimedia Commons / Public DomainThe first Public Health Act was passed in 1848, six years after Edwin Chadwick published his report on the unsanitary living conditions of the working class. Chadwick had proposed this piece of legislation because he hoped to save the British government money by diminishing the poor's reliance on government funds and services. Many families needed government assistance due to losing members to infectious diseases like cholera.

The government sat on Chadwick's suggestions for a long time. It wasn't until another cholera outbreak in 1848 that the government finally passed the act, which generated a framework for towns to have medical doctors, proper sewage, means to dispose of trash, and clean drinking water.

However, there was little money and no oversight to ensure these frameworks were actually used.

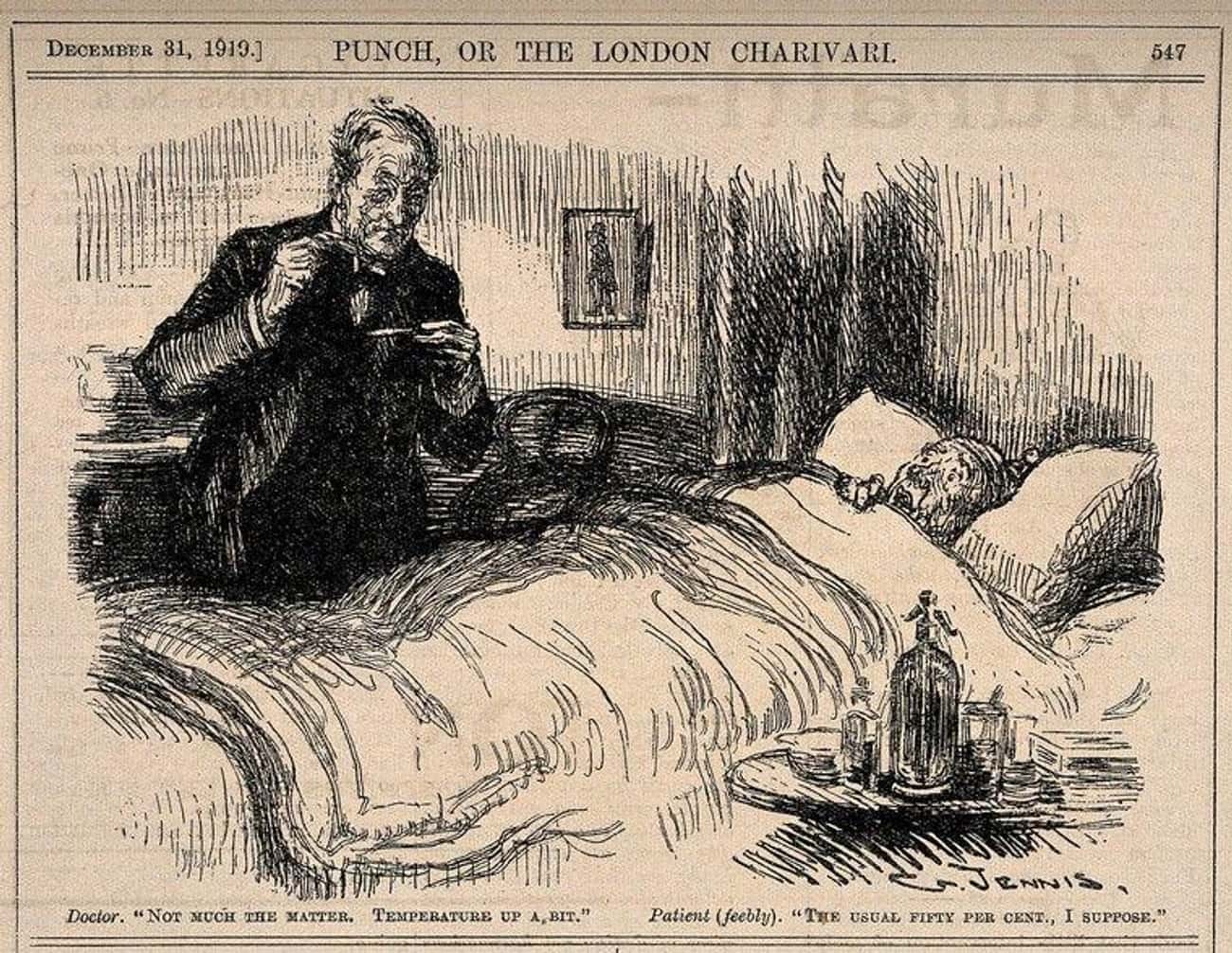

Doctors Of The Era Concluded That Disease Spread Through Bad Smells

Photo: G. Jennis / Wellcome Collection / CC BY 4.0Known as the miasma theory, the belief that disease spread via bad smells originated in the Middle Ages. By the 19th century, the belief was widely held throughout England.

Instead of focusing on bad sanitary practices, doctors focused on the foul-smelling air itself. Edwin Chadwick, who authored some of the most important reports and legislation related to sanitation, also subscribed to this theory. Under his supervision, refuse was discarded into the Thames River to curb the odors contaminating the streets of London.

If the plan was to curb bad odors, it backfired spectacularly. After centuries of dumping waste into the river, a particularly hot summer led to the Great Stink of 1858. The smell of the pollution was so foul that it eventually forced the government to enact major public works projects, including the creation of a proper sewage system.

Overcrowded Tenements Were Breeding Grounds For Smallpox

Photo: Thomas Annan / British Library / Public DomainHighly contagious, the smallpox virus causes rashes and scabs that can be fatal without the proper treatment. Though Dr. Edward Jenner created an effective vaccine for the virus in 1796, laborers in large cities were unaware, and the medical community did little to reach out to factory workers and their families.

The cramped tenement life was the perfect place for smallpox to transfer from person to person. Without the knowledge or resources to fight the virus, it spread like wildfire in the packed industrial apartment complexes.

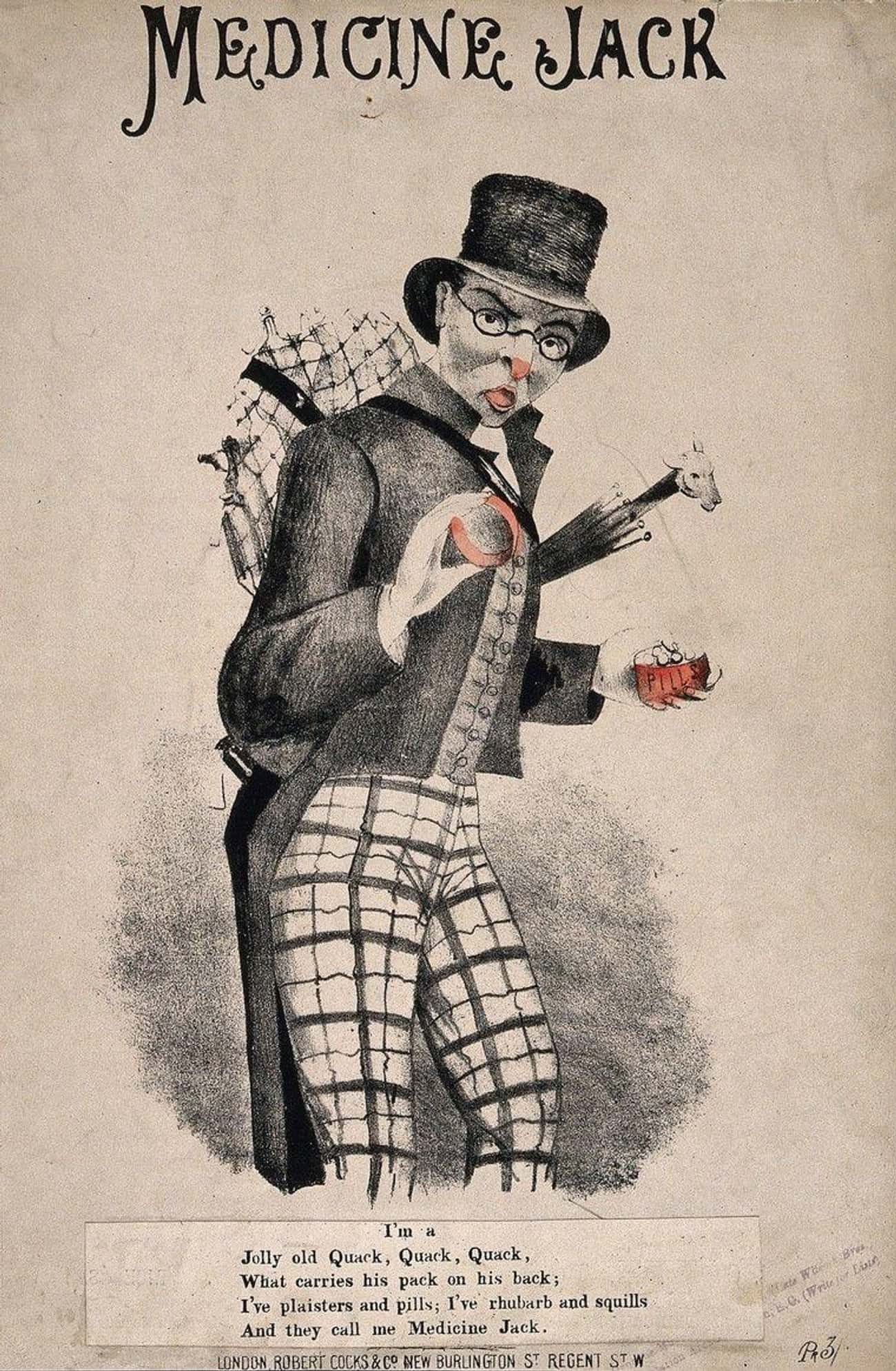

Street Vendors Sold Medication To The Impoverished On A ‘No Cure, No Pay’ Basis

Photo: Unknown / Wellcome Collection / CC BY 4.0The rise in urban development created a large working class in industrial England. When they were sick or close to passing, there was no basic medical aid available to them, meaning they were left to figure out how to take care of each other.

This created the perfect opportunity for profit-seeking street vendors to take advantage of those in need. Selling a plethora of patent medication without any liabilities, these "quack" doctors were often parodied in comics and advertisements during the 19th century.

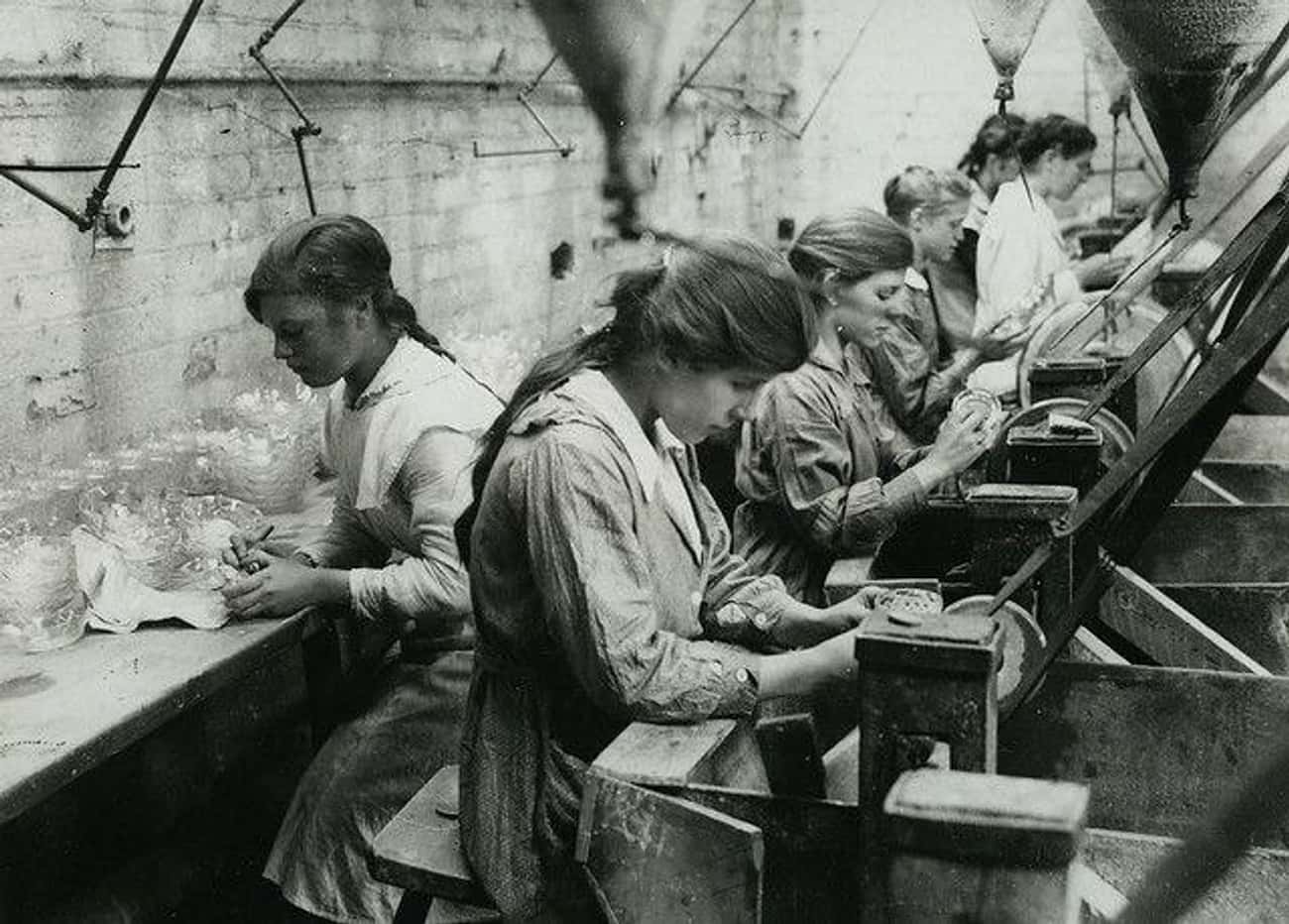

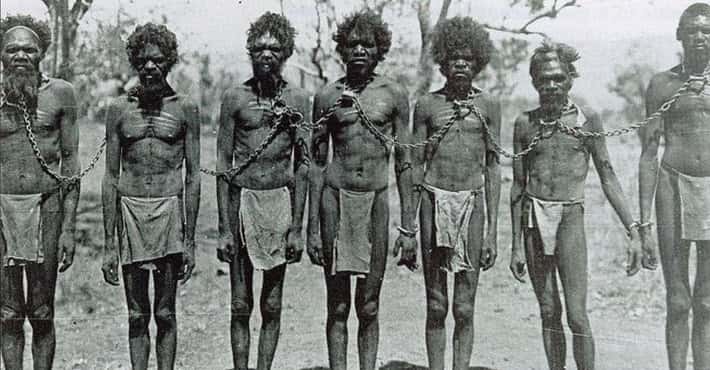

Child Workers Were Exposed To Hazardous Materials And Equipment

Photo: Unknown / Wellcome Collection / CC BY 4.0Child labor was the norm in the England of the Industrial Revolution. Children were forced to do the work adults could not, and they normally worked 10 to 14 hours a day. This led to an excess of health and physical developmental issues.

Without hygienic or medical standards, children were considered disposable by factory managers and accidents were commonplace due to unsafe working conditions. One letter on behalf of a 13-year-old girl involved in an accident attests to this. Robert Baker, the inspector of factories, wrote to the owners of the factory after the girl's hand was mangled. His letter, dated August 1859, reads in part:

I tell you fairly that I am not sure whether I have the power to recommend an action. If I had, I had much rather recommend this poor child to your favourable consideration. But since the wheels can be boxed off without detriment to the working of the machine, they ought to have been.... [I]f they had, even though the child was faint, the accident could not have happened: and therefore you are morally bound to do something for her by way of compensation.

It was not until 1901 that it was illegal for any child under 12 to work in British factories.

Disease Spread Further Due To The Stigmatization Of Ladies Of The Night

Photo: William Hogarth / British Library / Public DomainDuring the Industrial Revolution, becoming a lady of the night was a common way for working class women to make money. With a booming population, rising living costs, and few options for steady income, getting paid for intercourse became widespread. Without access to healthcare or contraception, these women became infected with diseases like syphilis. They spread these diseases to their clients, who then spread them to their wives or other partners.

Women of the streets were judged and subjugated by those in higher classes who believed their mere existence represented a disease that needed to be purged from British life. The stigmatization of this industry made it difficult to address the causes of venereal diseases, and the women paid for intercourse were blamed.

The Contagious Diseases Act of 1864 allowed police officers to target women they believed to be street workers, forcing them to undergo medical tests. If these women tested positive for diseases, they were confined for months at a time in order to "heal." Men were not required to participate in the same compulsory examinations.

This unequal treatment of women sparked an outcry among the public. Led by Josephine Butler, the founder of the Ladies' National Association, a grassroots campaign successfully overturned the act.

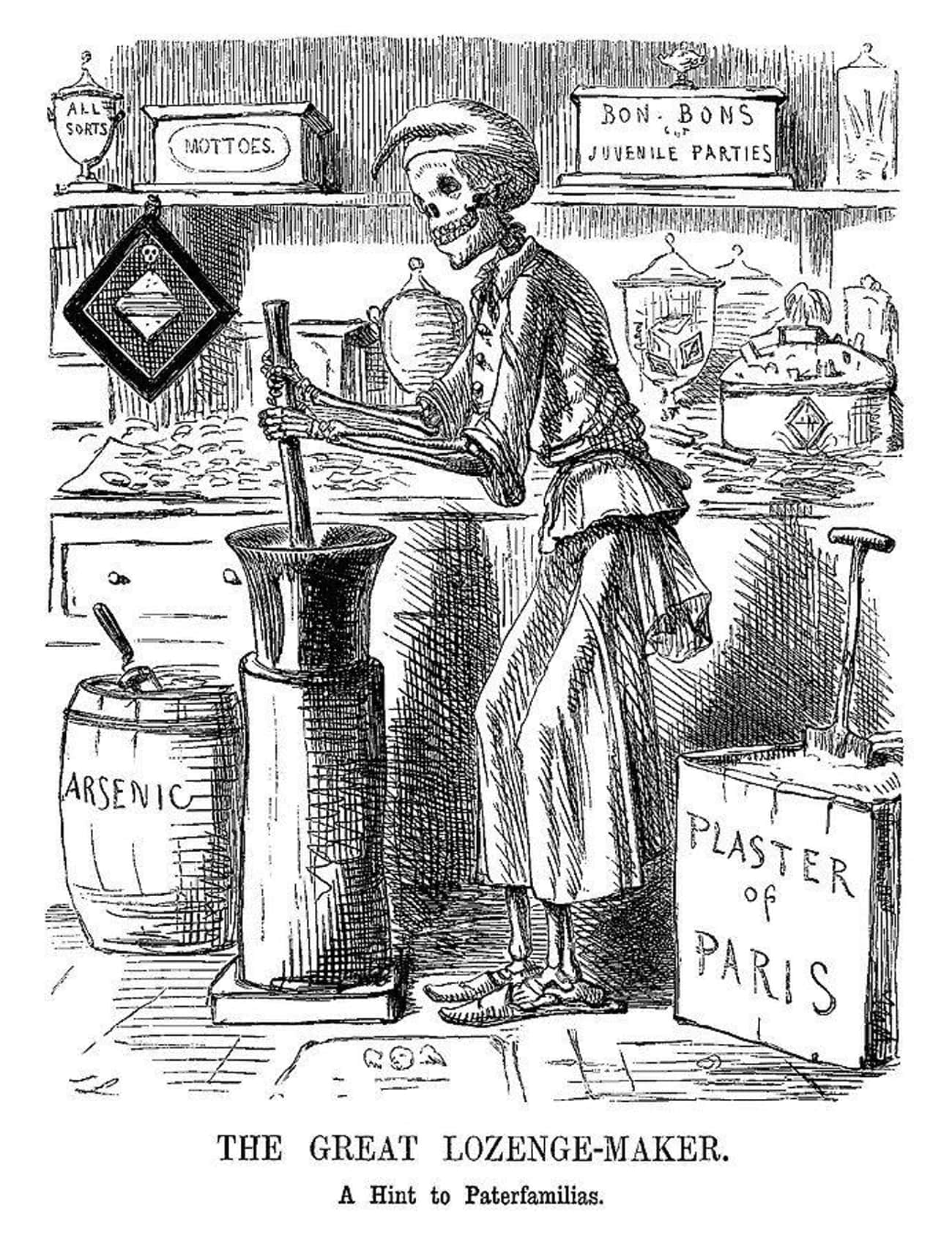

Exposure To Arsenic Led To Many Illnesses And Lost Lives

Photo: John Leech / Wikimedia Commons / Public DomainDuring the Victorian Era, arsenic was in just about everything, from food to drink to wallpaper to clothing. Doctors even prescribed arsenic to their patients. How is it that a substance now known to cause severe health issues and mortalities was so commonplace in industrial British life? A lack of advanced toxicology practices matched with the cost-saving benefits of using arsenic in household products (it was a common byproduct of burning mineral ores and coal) made it a popular ingredient for manufactured materials.

Factory workers were doubly exposed to this toxic substance. Without proper protection, ventilation, or standardized procedures, it was impossible for laborers to avoid direct contact with arsenic. Historian Lucinda Hawksley provides more insight into exposure for those with factory jobs:

The workers would dye these tiny, tiny pieces of wool or cotton in green, and while doing so would inhale them and the particles would stick to their lungs. The manufacturing process created a lot of dust from the dye - the dust had arsenic in it - and this created major problems for the factory workers as the dust would stick to their eyes and skin. If there were abrasions on their skin, the arsenic could get directly into their blood stream and [infect] them that way as well.

Contraceptives Were Only Available ‘Under The Counter’

Photo: Louis Lang / Wikimedia Commons / Public DomainIntercourse was a taboo subject in 18th- and 19th-century England, and there was no accessible birth control for the majority of sexually active people. Condoms did exist but were only available to those able to track them down and pay for them. This means that the option to avoid pregnancy was abstinence. The population skyrocketed during this time.

Without public health measures designed to educate and prevent pregnancy, working-class families grew beyond their means. Childbirth was also a risky affair for women. Maternal mortality rate estimates were 7.5 per 1,000 women from 1750 to 1800, and five per 1,000 women from 1800 to 1850.

More people meant less space, which led to cramped conditions, more slums, and less sanitary living standards. Without contraceptives, venereal diseases spread rapidly.