Davis was most important person out of pads NFL ever had

It was at a Hall of Champions function some 25 years ago that Alex Spanos first introduced me to Al Davis. Al knew who I was, all right.

Terribly inquisitive and a great listener _ he’d ask question after question in matters of players, people or things of interest _ he knew as much as he could discover about everyone who might affect him. I could see it in his eyes, so I didn’t know what to expect.

“You’ve been kind to us,” he said in that Brooklyn/Dixiespeak of his. “God bless you.”

By “us,” he was speaking not of his Oakland Raiders, because I certainly hadn’t (or haven’t) always been kind to the Silver and Black, but of Al Davis, because I had been a strong advocate for his induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame, which was terribly important to him, a validation.

Induction finally came in 1992, many years too late, but it probably was to be expected, because most media members were not fond of Al, or he of them, because he didn’t give a damn about most of us.

After the announcement from the Hall that Saturday afternoon in Minneapolis, veteran NFL writer Vito Stellino, himself a winner of the Hall’s McCann award in 1989, was interviewed on TV and said: “Al Davis going into the Pro Football Hall of Fame is like John Dillinger going into the banking hall of fame.”

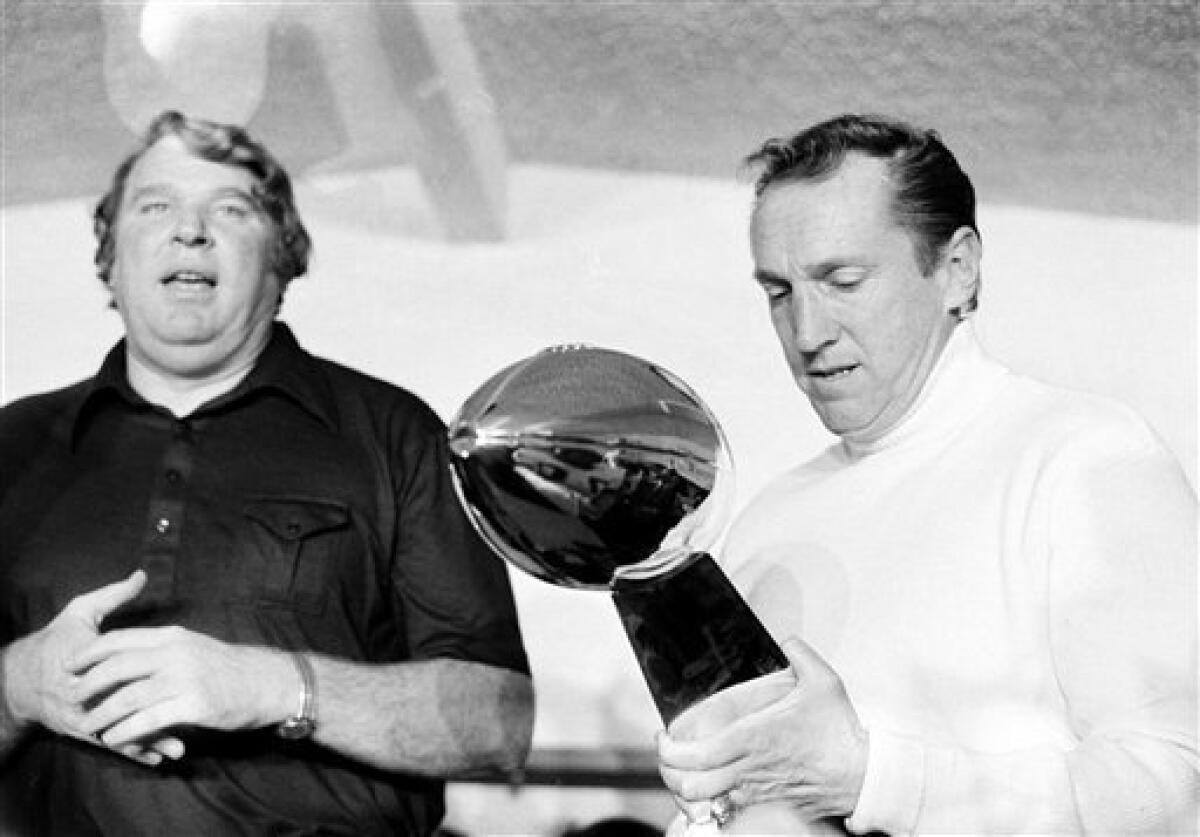

Classic Vito, but he was wrong. I make Al Davis, who Saturday passed away at 82, the single most important non-player in the history of professional football. More important than Rozelle, Halas, Brown, Bell, Lombardi, Rooney(s), all of them.

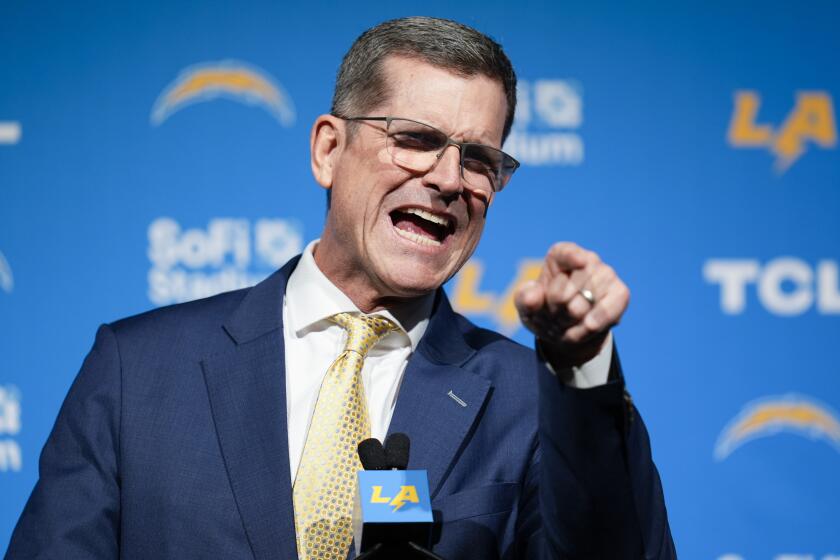

He went from scout to Chargers assistant under Sid Gillman, to head coach of Oakland, to general manager, to AFL commissioner, to Oakland owner. As AFL commissioner, he went after the NFL’s jugular, its quarterbacks. He was going to steal them. In the process, he strong-armed a merger that he really didn’t want.

Al wanted to win, as usual, but he preferred to bury the NFL, which had pooh-poohed his league. He probably saw the merger as a defeat. But it changed football forever. To even think of the game being what it has become without Davis is, well, unthinkable.

Plus, he called me Nicky, which is what my nieces and nephews call me. I remember standing next to him at the restroom urinals in Qualcomm Stadium at halftime of a Chargers-Raiders game not going in his favor.

“How’s it going, Al?”

“I’m all right, Nicky. My team’s not so good.”

Al was a corsair. A rebel. Bohemian. Some considered him devil reincarnate, and he probably relished it. Anything for an edge. He was a football man. He was litigious. He sued the NFL and won. He had the spine of a Sequoia. He moved his team from Oakland to L.A. and back to Oakland, unabashedly plundering millions along the way.

Al Davis was our day’s P.T. Barnum, fully realizing suckers were out there, and he had no problem outsmarting even the smartest of them. One of the great sports characters, and I love characters. Sorry, I liked Al Davis. I liked him plenty. He was a giant, at times vindictive (see Marcus Allen), but a man of great loyalty and compassion, the other side of his dark side we rarely saw.

Few people know that, when San Diego Union sports editor and columnist Jack Murphy was dying of cancer, Davis offered to send in specialists. He kept close ties with many important San Diegans after he left here in the early 1960s, and that probably spawned the feud between Davis and then-Chargers owner Gene Klein, a Rozelle sympathizer who hated Davis and vice versa. In fact, it was during the 1981 Raiders v. NFL antitrust trial here that Klein had a heart attack on the witness stand.

True story: At Murphy’s funeral, which Davis and Klein attended, Gene, a man I also respected, demanded to speak before Al, presumably so he could promote the idea of naming the stadium after Murphy before Davis got his chance.

But football was Al’s thing; the game, winning games, which hadn’t happened often in recent years. Chargers General Manager A.J. Smith made it a point to sit down with Davis prior to every draft to pick his brain – and allow Al to pick his.

“I never met a man who looked and acted with more confidence than Al Davis,” Smith says. “The presence he had. I will miss those talks.”

Not everyone will miss Al Davis, especially the goody-goody media hypocrites who now mourn his loss. This was An American Man. A robber baron, of sorts, a pirate, a throwback. This is a country founded by Al Davises, not choirboys.

When the Union and The Tribune merged in 1992, I wanted my first column to be on Al’s election to the Hall, and he consented.

“As a young guy, I had my dreams,” he said. “First to be a player. When I wasn’t successful at that, I wanted to build the finest organization in professional sports. I love this game; yes I do. There’s still a sense of urgency that burns within. The will to win. And I hope our organization will continue to win.

“The will to win is more important than any event.”

The only thing Al Davis feared was death itself. It obsessed him. That it finally caught up with him was inevitable. But it came after a tough, thrilling, unpredictable long run.