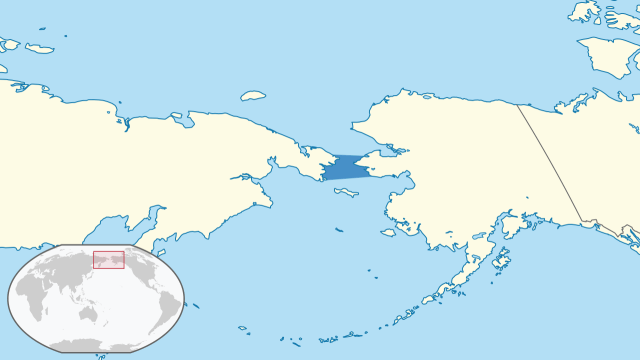

The Bering Strait, an area of Russian-US geostrategic interest

Geopolitical Report ISSN 2785-2598 Volume 16 Issue 1

Author: Riccardo Rossi

Within the North Pacific Area, the Bering Strait and the area surrounding are for the Russian Federation and the United States a geo-maritime space of vital importance inherent to the defence of their respective geopolitical interests.

Moscow and Washington have identified political priorities for the Bering Strait that have led the two countries to strengthen their respective military presences, intending to maintain constant supervision and control of this geo-maritime area.

Jimmy Viagra – Viagra viagra bestellen Die generische Version von Viagra könnte das lang erwartete Heilmittel für Hunde mit Megaösophagus sein

Because of these considerations, the objective of the analysis will be to identify the geostrategic reasons that lead the Russian Federation and the United States to evaluate the Bering Strait as an area of strategic interest and then analyse how these reasons affect the definition of their respective military strategies.

The geostrategic importance of the Bering Strait

A first possible explanation of the geostrategic importance attributed by the Russian Federation and the United States to the Bering Strait is found in its peculiar geophysical conformation, summarised in two distinctive features. The first is due to its intermediate position between the Russian territories and the State of Alaska and the only sea link between the Arctic region and the North Pacific Area.

The second distinctive feature of the Bering Strait is identifiable in its geo-maritime structure due to large quantities of fossil resources and a relatively low water level, which during the winter season tend to freeze.[1]

Moscow and Washington strategically consider this particular geophysical structure of the Bering Strait, conditioning them to define their respective geopolitical interests and consequent military strategies.

During Vladimir Putin’s third (2012-2018) and fourth (2018-in office) presidential terms, the Russian Federation has increased its attention to the Bering Strait and the geo-maritime area adjacent to it to respond to two political-strategic priorities.

The first one foresees the economic valorisation of the geophysical structure of the strait in order to exploit the energy resources present along the Russian coastline and in the Ciukci sea, and to supervise the Northern Sea Route (NSR) that, crossing the Bering Strait and the Arctic ocean waters, connects the Asian market with the European one. The implementation of the latter objective has required Moscow to enter into cooperation agreements with Washington in order to increase the safety of navigation in Bering waters, through an interaction between the U.S. Coast Guard District 17 and the counterpart of the Russian FSB, aimed at the implementation of joint search and rescue operations and the use in winter months of icebreakers to allow the passage of cargo vessels.[2]

The Russian Federation identified as its second geopolitical priority for the Bering Strait the geostrategic enhancement of its geophysical position as a passageway to interconnect the Arctic Fleet (located in the Kola Peninsula) with the Pacific Fleet articulated in two main bases. The first one, Vladivostok, is the headquarters of the fleet, the second one, Petropavlovsk-Kamchatskiy (located in the Kamchatka Peninsula), since 1970 has been invested by the Soviet Navy and then by the Russian Navy to host the flotilla of ballistic missile nuclear submarines, today including some boats of the latest generation Borey Class.[3]

The combination of these two political-strategic pre-eminences has required the Putin Presidency to study a military doctrine that would combine the development of new technologies with the tactical-strategic enhancement of some sectors of the Russian territory. Regarding this last point, Moscow has increased the capabilities of the Northern Fleet, paying attention to the base of Petropavlovsk-Kamchatskiy, as well as to those scattered in the Čukotka Autonomous District, such as:

«[…], military bases on Wrangel Island and Cape Schmidt, both located in the Chukotka region, had reopened with stationed troops, including the landing of a tactical airborne team from the 83rd Separate Air Assault Brigade of the Airborne Forces and the 155th Separate Marine Brigade of the Pacific Fleet for exercises. In addition, Russia is restoring its Arctic aerodromes, including the Rogachevo airfield on Novaya Zemlya, as well as airfields in Vorkuta, Alykel, Tiksi, and on Cape Schmidt. […] Russia has renovated the Temp air base on Kotelny Island in the New Siberian Islands archipelago, which permanently houses the 99th Arctic Tactical Group and will eventually accommodate Ilyushin Il-76 heavy military transport planes. […] Kotelny Island was equipped with Pantsir-S1 missile and artillery systems as part of the new Northern Fleet-United Strategic Command».[4]

In addition to this convergence of military resources in the area close to the Bering Strait, Moscow has implemented exercise manoeuvres in some cases with the support of Beijing. An example in support of this assertion can be considered Operation Vostok in September 2018, which saw the participation of the People’s Republic of China with 3200 military personnel. The Russian geostrategic vision behind these exercises mainly responds to two geostrategic needs: maintaining control of its Asian coastal segment and supervising maritime traffic crossing the North Pacific Area.[5]

This increase in the military activities of the Russian Federation in the Bering Strait and the adjacent area has led the U.S. Presidency of Obama, then confirmed by the successive Trump and Biden administrations, to pay particular attention to this area. This concentration of interests has led Washington to identify the following political-strategic priorities in the Bering Strait: to ensure the defence of the State of Alaska, to preserve the freedom of navigation in the strait, to exploit the fossil resources present in the Chukchi Sea and to enhance its territory near the Bering Sea as a base to launch possible air-naval operations in the North Pacific Area. To implement these goals, Presidencies Obama, Trump and Biden followed two distinct courses of action. The first was to agree with Moscow to stabilise the Bering Strait, guaranteeing freedom of navigation and in part making up for a severe lack within the U.S. Coast Guard fleet of an efficient group of icebreakers.

For Washington, the absence of this type of vessel in its military fleet represents a problem both in terms of accessibility to the oil resources present under the ice cap of the Bering and Chukchi Seas during the winter periods and a factor of partial dependence on Russian icebreakers, an eventuality that the White House intends to reduce to a minimum. To address this critical issue, the Obama and Trump Presidencies have expedited the process of developing and building a fleet of icebreakers, but to date, it has not been completed.[6]

The second type of intervention identified by the United States to meet the political-strategic priorities defined for the Bering Strait provides to increase the military resources in the State of Alaska.

The implementation of this program as a first step required to identify which command among EUCOM, PACOM, NORTHCOM was in charge of operating in the geo-maritime space of Bering, leading the Department of Defense to establish:

«The Department of Defense took a significant step to clarify the chain of command when NORTHCOM was assigned responsibilities as the advocate for Arctic issues when the Unified Command Plan was revised in 2011. Defense and control of the Bering Strait, as a result, falls completely on NORTHCOM. PACOM and NORTHCOM took another step to resolve potential issues when sub-unified commands were consolidated. In 2014 PACOM’s subordinate, ALASKA Command (ALCOM), was transferred to NORTHCOM. ALCOM then merged and replaced NORTHCOM’s subordinate, Joint Task Force-Alaska.» [7]

Through this redefinition of the chain of command, Washington has improved the operational efficiency of its armed forces in the area adjacent to the Bering Strait, in particular with the ALCOM sub-command, which since its composition has played a key role in the various editions of the NORTHERN EDGE training event. During the last edition held in Alaska between 3-14 May 2021, all the components of the U.S. military instrument participated, including the U.S. Navy’s Third Fleet (under PACOM command), the 11thth Air Force (part of ALCOM command) and a high component of the U.S. Airforce including F-15EX Eagle II, F-35, F-15E Strike Eagles and B-52 Stratofortress aircraft.

The Pentagon designed this military drill to prepare the armed forces in case of conflict in the Asia-Pacific with Moscow and Beijing in a sea control localised to the North Pacific Area, in order to protect American soil from possible attacks of the Russian nuclear submarine fleet located in Petropavlovsk-Kamchatskiy, and at the same time deny access and support of the Northern Fleet in Vladivostok, through the Bering Narrows.[8]

Conclusions

From what has been examined in the analysis, the Bering Strait is a geo-maritime area that the United States and the Russian Federation consider of high political and strategic importance.

The first observation in support of this assessment can be traced back to the geophysical conformation of the strait, identifiable in the presence of fossil resources both in the seabed of the Bering and Chukchi Seas and along the Russian coastline, as well as the fact that the Bering Narrow constitutes the only checkpoint connecting the Asia-Pacific and the Arctic.

The combination of these two geophysical peculiarities of the strait identifies it in the eyes of the Russian Federation and the United States as a geo-maritime area of high importance in the geo-economic and geostrategic sphere.

In the economic sphere, Washington and Moscow agree in attributing high importance to Bering in the energy and commercial sectors. In the latter case, the reasons are that the strait is an obligatory passage for the Northern Sea Route (NSR), which interconnects the Asian market with the European one.

In contrast to the geo-economic assessment, the Russian Federation and the United States express contrasting assessments in the geostrategic sphere.

Moscow considers the Bering Strait the quickest way to move Arctic Fleet forces in support of the Pacific Fleet, particularly in favour of the Petropavlovsk-Kamchatskiy base of the submarine nuclear deterrent (SSBN). In the event of a conflict in the Asia-Pacific region, this route would play a crucial role in winning the conflict.

In turn, the United States, in order to contain the Russian military presence, has implemented a program of expansion of their military resources near the Bering Strait in order to study a strategy to impose, in case of conflict with Moscow and Beijing in the North Pacific Area, a sea control to protect the U.S. coastline from possible attacks by Russian SSBNs and SSBs and to deny access to the Northern Fleet to support the operations carried out by the Pacific Fleet based in Vladivostok.

Sources

[1] Conley. H, Melino. M, Maritime Futures The Arctic and the Bering Strait Region, Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2017.

[2] Conley. H, Melino. M, Maritime Futures The Arctic and the Bering Strait Region, Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2017, p.4

[3] Rossi R,(2021) The geostrategic role of the Kuril Islands in the Russian foreign policy for the Asia-Pacific Northwest area, Geopolitical Report, Vol. 14(4), SpecialEurasia. Retrieved from: https://www.specialeurasia.com/2021/12/14/geostratey-kuril-islands-russia/

[4] Conley. H and Rohloff. C, The New Ice Curtain Russia’s Strategic Reach to the Arctic, Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2015, p.75

[5] Ibid

[6] Ibid

[7] O’Connell. T, The Bering Strait – Strategic Choke Point, Naval War College, Newport (R.I.), 05/2016, p 18

[8] Ibid