Error, Jordan: John Stockton deserved better from ‘The Last Dance’

Michael Jordan cussed out Isiah Thomas, challenged Magic Johnson, brushed off Clyde Drexler, laughed at Gary Payton, and cast Charles Barkley and Karl Malone as motivational devices.

Indeed, some of the best moments of “The Last Dance,” ESPN’s 10-part documentary about the 1990s Chicago Bulls that wrapped on Sunday, came when the basketball legend trained his sights on his former foils. Jordan hasn’t forgiven Thomas for refusing to shake hands. He wrestled control of the Dream Team away from Johnson during a heated practice. He appeared disgusted that media members ever wanted to compare him to Drexler, or that Payton thought his defense bothered Jordan. He hasn’t forgotten that Barkley and Malone beat him out for MVP honors in 1993 and 1997, respectively.

The 10-hour documentary moved too quickly through key on-court moments at multiple times. That was inevitable, given the scope of the project and the richness of Jordan’s career. But the project would have benefited greatly from a more thorough treatment of John Stockton, a Hall of Famer who embodied Jordan’s signature drive as well as any player from that era.

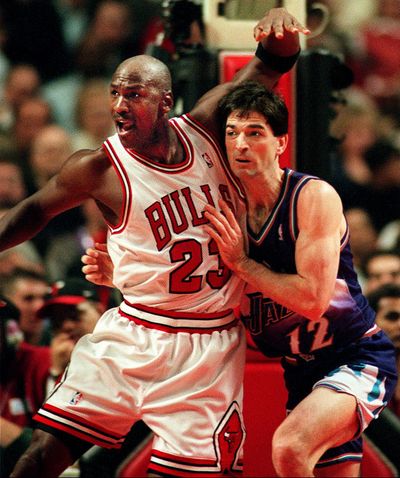

Jordan and Stockton seem to have little in common at first glance. Start with their shorts: Jordan wore his loose and longer, while Stockton’s were as short and tight as possible. Jordan meticulously shaved his head; Stockton got the Supercuts special. Jordan rocked the most popular sneakers in the game; Stockton wore dad shoes.

Jordan hit an NCAA title-winning shot as a freshman at North Carolina; Stockton never made the tournament at Gonzaga. Jordan was NBA rookie of the year at age 21; Stockton wasn’t a full-time starter until his fourth season. Jordan rose to global prominence with the big-city Chicago Bulls; Stockton plied his trade with the small-market Utah Jazz.

The 6-foot-6 Jordan was wired to attack and score. The 6-1 Stockton wanted to dish and defer. Jordan averaged 37.1 points for a season; Stockton never once scored 35 points in an NBA game. Jordan lived to talk trash; Stockton was mute. Jordan broke the sport with creative drives and acrobatic finishes; Stockton was all about fundamental bounce passes and sharp cuts. “Air” Jordan won dunk contests and posterized rivals; searching “John Stockton dunk” on YouTube doesn’t yield much at all.

And then there’s the difference that everyone remembers: Jordan won six championships, including two against the Jazz, casting Stockton into the pile of ringless stars alongside Malone and Barkley. At their cores, though, Jordan and Stockton were two sides of the same coin: intelligent, consistent, controlled two-way players who were utterly obsessed with winning. Fearless too.

“I never said ‘Oh my goodness, this is the Bulls,’ ” Stockton said in the documentary. “I sure didn’t feel an aura about Michael Jordan or the Bulls. I don’t know how you would play against somebody with that.”

Stockton never had any time for narratives or mythmaking, not even when he entered the Hall of Fame alongside Jordan in 2009.

“Jordan makes one big shot and everybody thinks he’s kind of cool. I don’t get it,” Stockton quipped nervously, racing through a self-deprecating speech so that he could cede the stage to Jordan. “I had to be the only draftee who was still living at home with his parents.”

A shy personality and intentional lack of charisma guaranteed that Stockton wouldn’t captivate ESPN’s audience such as Thomas, Johnson or Payton. But his resume was breathtaking, and it must be understood to properly set the stakes for the Bulls’ fifth and sixth title. After all, Stockton hit a series-clinching 3-pointer against the Houston Rockets to send the Jazz to the 1997 Finals. He also nailed a huge 3-pointer moments before Jordan’s famous “Last Shot” over Bryon Russell in the 1998 Finals.

Stockton never missed the playoffs during his 19-year career. He led 11 50-win teams and three 60-win teams. He made 10 straight all-NBA teams, earned nine straight All-Star nods and led the league in assists nine straight times. He didn’t miss a single game due to injury or rest in 17 different seasons. His 15,806 career assist tally is perhaps the sport’s most unbreakable record – no other player has reached 12,100. His 3,265 steals are also a record, topping any active player by more than 1,000.

His peers took notice. Barkley called him “one of the five best players I’ve ever played against” and “the perfect point guard.” Jason Kidd said Stockton and Johnson were the two best point guards of all time. Chris Webber once told the Dan Patrick Show that Stockton “would come to the game literally in a minivan, pop his kids out, and bust us up.”

Thomas said that Stockton “made Malone,” hailing the point guard’s “toughness physically and mentally.” On multiple occasions, Payton has argued that Stockton, not Jordan, was the most difficult player he guarded due to his constant movement.

Yet younger viewers of “The Last Dance” would be forgiven if they came away believing that Jordan’s biggest challenges in 1997 and 1998 were food poisoning and Russell. The relentless force of Stockton-to-Malone, a combination that sparkled for more than a decade, was undersold for two reasons: Malone was apparently not interviewed, and Jordan didn’t address Stockton.

Like Jordan, Stockton worked and worked at every step of his career. Like Jordan, he never settled or cut corners. Like Jordan, he mastered a potent offense and memorized opponent tendencies on defense. Like Jordan, his unforgiving approach chafed opponents. Like Jordan, he won at a high level for more than a decade. If not for Jordan, he almost certainly would have at least one ring.

In the documentary’s signature scene, Jordan was moved to tears by the notion that competition was the only thing that mattered to him.

“I wanted to win, but I wanted my teammates to win and be a part of that as well,” he said. “I’m only doing it because it is who I am. That’s how I played the game. That was my mentality. If you don’t want to play that way, don’t play that way.”

If any of Jordan’s contemporaries played that way, it was Stockton.