- Information

- AI Chat

AJ Van der Walt & NL Sono The law regarding inaedificatio A constitutional analysis (2016 )

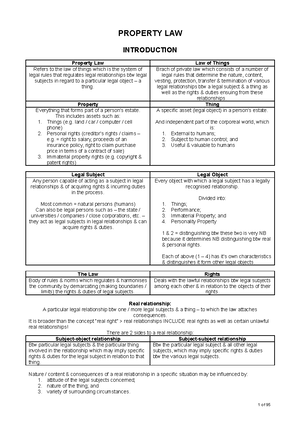

Property Law

Recommended for you

Students also viewed

- Shoprite Checkers (Pty) Limited v Member of the Executive Council for Economic Development, Environmental Affairs And Tourism, Eastern Cape and Others 2015 (6) SA 125 (CC)

- Chapters 15 - 17 - termination of possession, intro to other types of limited real rights, and servitudes and restrictive covenants

- Ownership in property law and case summary

- March notes prop law - land restitution

- Topic 15 REAL Security - Lecture notes 15

- Ngcukaitobi Bishop Article ( Final) for the expropriation

Preview text

195

The law regarding inaedificatio :

A constitutional analysis

∗

AJ van der Walt B Iur et Art LLB LLD LLM Distinguished Professor and South African Research Chair in Property Law, Stellenbosch University

NL Sono LLB LLM Doctoral Candidate and Research Intern, South African Research Chair in Property Law, Stellenbosch University

OPSOMMING Die reg insake inaedificati o: ’n Grondwetlike beskouing Die vraag of (en wanneer) roerende sake onroerend raak deur bebouing is lank reeds omstrede kwessie. In vroeë regspraak is aangedui dat die howe die aard van die roerende saak, die wyse en graad van aanhegting en die bedoeling van die aanhegter sal oorweeg, maar sedertdien is die toets nie altyd konsekwent toegepas nie. In die literatuur word soms aangevoer dat die howe stelselmatig wegbeweeg vanaf sogenaamd klassieke benade- ring, waarvolgens objektiewe faktore soos die aard van die roerende saak en die wyse van aanhegting die deurslag gee, na sogenaamde nuwe benadering, waarvolgens die subjek- tiewe bedoeling van die aanhegter 3 en soms die eienaar van die roerende saak 3 deur- slaggewend is. In hierdie artikel redeneer die outeurs dat daar selfs in die ouer regspraak soms tekens van meer subjektiewe benadering is en dat die sogenaamde verskuiwing na nuwe benadering nie noodwendig deur die regspraak gesteun word nie. Daar is bowen- dien heelwat oortuigende kritiek in die akademiese literatuur teen sodanige verskuiwing. Van meer belang, volgens die outeurs, is tekens in die regspraak dat die howe skynbaar in bepaalde gevalle, spesifiek waar eiendomsreg op die roerende saak ingevolge krediet- ooreenkoms as sekerheid voorbehou is, gewillig is om sterker op die subjektiewe bedoeling te fokus en te beslis dat aanhegting nie plaasgevind het nie, mits sodanige bevinding nie lynreg met die objektiewe realiteite bots nie. Die vraag is of sodanige tendens in die regspraak, wat waarskynlik op beleidsoorwegings ten aansien van krediet- sekerheid berus, grondwetlik geldig sou wees. Die outeurs argumenteer dat beslissing waarvolgens aanhegting wel plaasgevind het, en as gevolg waarvan die eienaar van die roerende saak van sy of haar eiendom ontneem word, waarskynlik nie op arbitrêre ont- neming vir doeleindes van artikel 25(1) van die Grondwet neerkom nie, mits die beslis- sing op grond van die gemeenregtelike beginsels van aanhegting berus. Indien die howe op grond van beleidsoorwegings in bepaalde gevalle sou beslis dat aanhegting nie plaas- gevind het nie, en weer eens mits die beslissing met die gemeenregtelike beginsels ver- soenbaar is, sou die eienaar van die onroerende saak (wat op grond van die beslissing

∗ This article is largely based on sections from the LLM dissertation of Sono Developing the law regarding inaedificatio : A constitutional analysis (US 2014).

Electronic copy available at: ssrn/abstract=

196 2016 (79) THRHR

nie deur die aanhegting vergroot is nie) geen grondwetlike eisoorsaak ingevolge artikel 25(1) hê nie omdat hy of sy in geen stadium reg in eiendom gehad het waarvan hy of sy deur die beslissing ontneem is nie.

1 INTRODUCTION

The test for determining whether or not a movable structure has attached to land to the extent that it has become part of the land through inaedificatio is complex and controversial. In Olivier v Haarhof & Co the court stated that <the question whether a structure is movable or immovable is one which depends on the cir- cumstances of each case=. 1 According to that decision, the factors that need to be considered are the nature of the structure; the manner in which the movable is fixed to the land; and the intention of the person who erected the movable. 2 The first two factors have become known as the objective and the third as the sub- jective factor. It is said that the application of these factors, in particular the sub- jective factor, has resulted in courts adopting different approaches to determine whether inaedificatio has taken place, namely, the traditional approach, the new approach and the so-called omnibus approach. 3 The existence of these approaches is confirmed by case law. 4

Generally, early case law is associated with the traditional approach, which considers the objective factors as the most important to determine accession; while case law after 1978 is said to indicate a shift from the traditional towards the new approach, which emphasises the subjective factor. This alleged shift from the traditional towards the new approach has been the subject of debate and criticism in academic literature. 5 The major issue in the debate is the priority that the more recent case law, associated with the new approach, gives to the third factor (the intention of the owner of the movable). In a certain line of cases asso- ciated with the new approach, the owner9s declared intention to retain ownership of the movable is of paramount importance, particularly in cases where the mov- able is subject to an instalment or credit transaction. 6 In these cases, the courts seem to protect the interests of the owner of the movable who has sold his prop- erty but retained ownership in terms of the instalment or credit transaction.

1 Olivier v Haarhof & Co 1906 TS 497 499. 2 In Olivier 500, Innes CJ put it as follows: <The points chiefly to be considered are the na- ture and objects of the structure, the way in which it is fixed, and the intention of the per- son who erected it.= 3 Van der Merwe <Things= 27 LAWSA (1st reissue 2002) para 337. See Knobel <Accession of movables to movables and inaedificatio 3 South Africa and some common law coun- tries= 2011 THRHR 299; Knobel <Intention as a determining factor in instances of acces- sion of movables to land 3 Subjective or objective?= 2008 De Jure 1563157; Badenhorst, Pienaar and Mostert Silberberg and Schoeman’s The law of property (2006) 1483149 (hereafter Badenhorst et al ); Maripe <Intention and the original acquisition of ownership: Whither inaedificatio ?= 1998 SALJ 5463548. The omnibus approach featured in just one decision, therefore we disregard it for purposes of this article. 4 Unimark Distributors (Pty) Ltd v Erf 94 Silvertondale (Pty) Ltd 1999 2 SA 986 (T) 9983 999; Konstanz Properties (Pty) Ltd v Wm Spilhaus en Kie (WP) Bpk 1996 3 SA 273 (A) 281. See also De Beers Consolidated Mines Ltd v Ataqua Mining (Pty) Ltd [2007] ZAFSHC 74 (13 December 2007) para 25; Chevron South Africa (Pty) Ltd v Awaiz at 110 Drakensburg CC [2008] 1 All SA 557 (T) 5683569. 5 See para 3 below. 6 See, eg, Melcorp SA (Pty) Ltd v Joint Municipal Pension Fund (TvI) 1980 2 SA 214 (W).

Electronic copy available at: ssrn/abstract=

198 2016 (79) THRHR

attached to it permanently. Grotius argues that fixtures are understood to be sold with the house. 12 Therefore, Roman-Dutch law also considered this principle to mean that everything permanently built onto or attached to land became the property of the landowner.

The principle of inaedificatio 13 was applied and developed in South African case law, albeit nowadays with a different understanding of the legal process that occurs when movables are permanently attached to land. Inaedificatio occurs, for instance, when building materials, pumps, equipment or other objects and struc- tures (being movable in nature) are permanently attached to land or other im- movable property. 14 In terms of the principle omne quod inaedificatio solo cedit , more commonly formulated as superficies solo cedit , it is said that everything that is permanently built on or attached to land becomes the property of the land- owner. 15 Acquiring ownership of movable property by inaedificatio is classified as an original mode of acquiring ownership 16 because ownership is not trans- ferred from one person to another and consent is not required for ownership of the movable to vest in the acquirer. 17 In fact, however, it is now widely recog- nised that ownership of the movable is not acquired by the landowner, because the movable ceases to exist as an independent legal object when it becomes per- manently attached to land. When inaedificatio takes place, the owner of the mov- able loses ownership of that object by operation of law because the movable ceases to exist independently once it becomes permanently attached to land. Consequently, the former owner of the movable cannot reclaim ownership on the basis that he did not intend to transfer it to the landowner. Similarly, the land- owner owns the same property as before accession took place (the land), but that land now includes a permanently-attached structure that did not exist before.

South African courts have found it difficult to determine whether a movable structure has become permanently attached to land, resulting in different ap- proaches to the application of the factors set out earlier. The traditional and the new approaches are discussed briefly below.

2 2 Case law associated with the traditional approach

The traditional approach was developed in MacDonald Ltd v Radin and The Potchefstroom Dairies & Industries Co Ltd , 18 where the court per Innes CJ ap- proved the three factors that were identified in Olivier v Haarhof & Co , 19 namely,

12 Grotius 3 8 1. 13 Also referred to as <building=. For purposes of this article, we disregard other forms of accession. 14 Badenhorst et al 147. 15 Van der Merwe <Things= para 337. See also Cowen New patterns of landownership: The transformation of the concept of ownership as plena in re postestas (1984) 58; Hall Maasdorp’s institutes of South African law Vol 2 The law of property (1976) 47348. 16 Unimark Distributors 9973998. 17 Badenhorst et al 72. See also Breitenbach <Reflections on inaedificatio = 1985 THRHR 4633464. 18 1915 AD 454. See Unimark Distributors 998; Konstanz Properties 281. See also Pope < Inaedificatio revisited: Looking backwards in search of clarity= 2011 SALJ 128; Baden- horst et al 149. 19 1906 TS 497 500.

INAEDIFICATIO : A CONSTITUTIONAL ANALYSIS 199

the nature and object of the movable; the manner in which the movable is fixed to the land; and the intention of the person who erected the movable. It is gen- erally assumed that case law associated with the traditional approach emphasised the first two (objective) factors and only considered the third (subjective inten- tion) if the first two did not indicate conclusively that inaedificatio had occurred. 20 According to Badenhorst et al , 21 this approach is best illustrated by the following dictum in MacDonald :

<The importance of the first two factors is self-evident from the very nature of the inquiry. But the importance of intention is for practical purposes greater still; for in many instances it is the determining element. Yet it is sometimes settled by the mere nature of the annexation. The article may be actually incorporated in the realty, or the attachment may be so secure that separation would involve substantial injury either to the immovable or its accessory. In such cases the intention as to permanency would be beyond dispute.= 22

In this explanation, the intention of the owner of the movable seems to be im- portant, but it plays a role only if the objective factors are inconclusive.

The traditional approach goes even further. The method for ascertaining the intention of the owner of the movable is outlined in Standard-Vacuum Refining Co v Durban City Council , 23 where Van Winsen AJA confirmed that intention is the most important factor, 24 but added that to determine whether the intention was to attach the movable permanently, regard had to be given to the nature of the movable, the method and degree of attachment to the land, and whether the movable could readily be removed without injury to itself or to the land to which it was attached (the objective factors). In other words, although intention is con- sidered the most important factor, it is inferred from the objective factors. This means that the objective factors are <not regarded as totally independent from the intention with which the attachment took place=. 25 The objective factors are con- sidered with the object of arriving at what may best be described as an objective or inferred intention. If a movable is attached to land to the extent that separation would cause damage to the land or the movable itself, this would give rise to an inference that the movable was attached to the land with the intention that it be- comes permanent.

20 MacDonald Ltd v Radin and The Potchefstroom Dairies & Industries Co Ltd 1915 AD 454; Newcastle Collieries Co Ltd v Borough of Newcastle 1916 AD 561; Van Wezel v Van Wezel’s Trustee 1924 AD 409; Land and Agricultural Bank of SWA v Howaldt and Vollmer 1925 SWA 34; R v Mabula 1927 AD 159; Gault v Behrman 1936 TPD 37; Petter- sen v Sorvaag 1955 3 SA 624 (A); Edwards v Barberton Mines Ltd 1961 1 SA 187 (T); Caltex (Africa) Ltd v Director of Valuations 1961 1 SA 525 (C) 528. See Pope 2011 SALJ 128; Badenhorst et al 149; Van der Merwe <Things= paras 3373338. 21 Badenhorst et al 148. 22 MacDonald 467. 23 1961 2 SA 669 (A). 24 Cases that describe intention of the owner of the movable as the most important factor in- clude MacDonald 468, where Innes CJ regarded intention as important and stated that con- sidering the intention of the owner is what is expected in view of the fundamental principle that a non-owner cannot transfer the property of another, although this is subject to a few exceptions. See also Land and Agricultural Bank of SWA 37338; Champions Ltd v Van Staden Bros and 1929 CPD 330 3333334; Johnson & Co Ltd v Grand Hotel and Theatre Co Ltd in Liquidation 1907 ORC 42. 25 Badenhorst et al 148.

INAEDIFICATIO : A CONSTITUTIONAL ANALYSIS 201

plant, a projection room, and a dimmer-board with ancillary fittings and attach- ments. To determine whether these items were permanently attached to the building the court held that the test is whether the annexor, at the time of attach- ment, intended that these items should remain permanently attached. 32 The court stated that evidence as to the annexor9s intention regarding the permanency of the attachment can be determined from numerous factors, including the annexor9s own evidence as to his intention ( ipse dixit ); the nature of the movables and of the immovable; the manner of annexation; as well as the cause for and circum- stances that gave rise to the annexation. To establish whether the movables were annexed with the intention to remain there permanently, the court took into con- sideration the intended duration of the original contract of lease; the possibility of renewing the lease; the fact that the building had been built to operate as a theatre; and the fact that the seats, emergency lighting and dimmer-board were essential equipment of the theatre. 33 Accordingly, the court held that the mov- ables in this case were intended to remain permanently attached to the building. 34

In Melcorp the question was whether certain lifts had become immovable as a result of their installation in a building. The court stated that the question whether the components of the lifts had acceded to the building is a question of fact that needs to be decided on the circumstances of the case. 35 To establish whether the lifts were permanently attached to the building, the court analysed evidence re- garding the degree and manner of attachment, 36 concluding that there was no in- dication that the lifts were attached in such a manner that their removal would cause substantial injury to the building, and that the lifts could be separated from the building without any difficulty. Consequently, the degree and manner of the annexation of the lifts did not result in an unavoidable conclusion that they had been attached permanently. However, the defendant argued that the lifts were an integral part of the building, which could not be used for its intended purpose without the lifts. Furthermore, although the lifts could be removed from the building <without causing any damage, the intention behind its installation [could] only [have] be[en] that it should remain in the building with a degree of perma- nence=. 37 The court upheld the defendant9s contention that the lifts were an in- tegral part of the building, but came to the conclusion that the lifts nevertheless remained movable. 38 Only <[i]f those facts [regarding the lifts being an integral part of the building] stood alone it would be a proper and necessary inference that the person who installed the lifts intended them to form a permanent part of the structure and consequently that they acceded to it=. 39

One can argue that Melcorp was primarily concerned with the intention of the plaintiff as expressed in the contract of sale, which stated that the lifts would re- main movable until they were paid for in full. 40 Against the background of the fact that the court conceded that the nature of the lifts as well as their function as

32 Theatre Investments 688. 33 691. 34 Ibid. 35 Melcorp SA 216. 36 217. 37 220. 38 Badenhorst et al 150. 39 Melcorp SA 222. 40 224. See Badenhorst et al 150.

202 2016 (79) THRHR

an integral part of the building suggested that they were intended to be attached to the building for permanent use, this could create the impression that the inten- tion of the owner of the movables as stated in the contract of sale could override the objective indications of accession. The question is whether the expressed intention of the owner should override the intention to attach permanently that can be inferred from the nature and function of the lifts. 41 In what seems to be a response to this question, the court stated that <the value of the so-called ipse dixit of the annexor... [will] vary from case to case=. 42 According to the court, it will be important in certain cases to ascertain the so-called real intention as in- ferred from physical factors and not the professed intention as stated in the con- tract. This means that in certain cases the objective factors may be conclusive of the intention of the annexor of the movable property. 43 For instance, the owner of cement who uses it or allows it to be used to build an immovable structure can- not rely on a reservation-of-ownership clause to contest the inference that his intention was for the cement to become part of the immovable structure. 44 There- fore, if the lifts in Melcorp were attached to the building in such a way that they could not be removed, the real intention as inferred from the physical factors would not be trumped by the professed intention in the contract.

Konstanz Properties (Pty) Ltd v Wm Spilhaus en Kie (WP) Bpk 45 is also said to support the so-called new approach to inaedificatio. In Konstanz the question was whether a certain irrigation and circulation system had become permanently attached to the land. The court considered the decision in MacDonald 46 and held that the intention of the owner of the movable, and not of the annexor, had to be considered to establish whether accession had occurred. 47 The appellant in Kon- stanz argued that it was not necessary to consider the intention of the owner of the movable, since the nature and manner in which the irrigation and circulation system had been attached to the land indicated that the attachment was perma- nent. 48 However, the court decided that since the appellant did not argue that the approach in MacDonald should be reconsidered, the court had to accept that the test in MacDonald was still applicable and concluded that inaedificatio had not taken place because the contract provided for retention of ownership of the mov- ables by the owner until the full purchase price has been paid. 49 Furthermore, it was not impossible to remove the items in question. A significant feature of this decision is that, although the court stated explicitly that the intention of the owner of the movable is not merely important, but in fact decisive, the court suggested that this position might be reconsidered in future in view of academic criticism. 50

41 Melcorp SA 222. See Pope 2011 SALJ 142. 42 Melcorp SA 223. 43 223. McEwan J stated that <[i]n such event clearly any statement to the contrary by the an- nexor would be disregarded=. 44 Badenhorst et al 147. 45 [1996] 2 All SA 215 (A). 46 1915 AD 454 466. 47 Konstanz Properties 276. See Van Vliet <Accession of movables to land: II= 2002 Edin LR 2063207. 48 Konstanz Properties 283. 49 282. 50 See Badenhorst et al 152; Van der Merwe <Things= para 339; Van Vliet 20 02 Edin LR 2063207. Van der Merwe <Things= para 339 argues that the decision has opened the door for a complete reconsideration of this area of the law in a future case before the Supreme Court of Appeal.

204 2016 (79) THRHR

of the owner of the movable is criticised for confusing the original and derivative modes of acquisition of real rights. The distinction between the original and de- rivative modes of acquisition hinges on the question whether the acquisition of the property results from an agreement between a transferor and a transferee or by operation of law, that is, whether or not the co-operation of a predecessor in title is required. 54 Acquisition is original if ownership is not derived from any predecessor or if the thing upon which ownership is acquired was res nullius. Original acquisition does not require consent. 55 Consequently, if inaedificatio occurs, ownership of the movable is lost without any regard for the intention of the owner of the movable, since ownership of the movable is not transferred from one person to another, but lost by the former owner when the movable ceases to exist independently when it is incorporated into the property of another by operation of law. 56 Conversely, acquisition is derivative if ownership of movable property is derived from the previous owner through transfer. A bilateral juridi- cal act is required to transfer ownership of the movable to a new owner 57 and, as a result, the intention of the owner of the movable will always play a central role in cases where the transfer of ownership is derivative. By contrast, academic authors argue that the two forms of acquisition have been confused in accession cases that focus on the intention of the owner of the movable, particularly in the form of direct evidence, to establish whether accession had taken place. 58

The emphasis that is placed on the intention of the owner of the movable is also criticised for confusing the rules of property with those of contract. Freedman argues that the emphasis on intention undermines the principles of property law, since it allows elements of contract law to play an unwarranted role in inaedifi- catio , which has nothing to do with consensual transfer of property. He main- tains that it is important to retain the fundamental distinction between the law of property and the law of obligations. 59 It seems that the emphasis that is placed on intention allows a contractual undertaking (in the form of the reservation of ownership in the contract of sale of the movables) to trump proprietary rights that were acquired originally. 60 Pope argues, along similar lines, that placing so much emphasis on the agreement governing the sale of the movable may distract the courts from the core issue, which is whether accession has occurred and not whether the owner of the movable intended to transfer ownership in the event of the purchase price being paid in full. 61

________________________

should the element of subjective intention play?= 2 000 SALJ 6673676; Van der Merwe and Pienaar <The law of property (including real security)= 1999 ASSAL 2903293; Maripe 1998 SALJ 5443552; Sonnekus and Neels Sakereg vonnisbundel (1994) 72; Breitenbach 1985 THRHR 4623465; Carey Miller <Fixtures and auxiliary items: Are recent decisions blur- ring real rights and personal rights?= 1984 SALJ 2053211. 54 Unimark Distributors 1000. See Badenhorst et al 71372 137. 55 Badenhorst et al 72; Breitenbach 1985 THRHR 4633464. 56 See 2 1 above. 57 Badenhorst et al 72. 58 Badenhorst et al 150. See Knobel 2012 CILSA 81; Sonnekus and Neels Sakereg vonnis- bundel 72. 59 Freedman 2000 SALJ 674. 60 Carey Miller 1984 SALJ 207. 61 Pope 2011 SALJ 143.

INAEDIFICATIO : A CONSTITUTIONAL ANALYSIS 205

Finally, the role of the intention of the owner in the new approach does not only confuse principles of property and contract law, it also conflicts with the publicity principle. 62 According to the publicity principle, a real right as well as its content and the identity of its holder should be made known and published to the world at large. 63 Van der Merwe asserts that the publicity principle attaches greater im- portance to outward appearance (objective factors) regarding transfer of owner- ship than to the subjective intention of the owner of a movable who may have re- served ownership prior to attachment. 64 The publicity principle seeks to protect third parties who might hold or acquire interests in the land. To comply with the publicity principle in cases of inaedificatio the landowner9s rights to anything that is permanently attached to his land should be made known to the public at large. 65 This is because third parties are likely to rely on the physical appearance that movables are permanently attached to the land and to conclude that they form part and parcel of that land. On this basis, Van der Merwe argues that the new approach undermines the publicity principle in that it regards the intention of the owner of the movable as more important than the outward appearance cre- ated by the apparent fact of physical attachment, based on the nature and purpose of the movable property and the degree and manner of its attachment. Con- sequently, it might prejudice third parties, like prospective mortgagees and pur- chasers, who rely on outward appearances and who are likely to assume that everything attached to the immovable forms part of it and belongs to the landowner.

The analysis above indicates that academic commentators are of the view that the intention of the owner of a movable should not play a conclusive role in de- termining whether accession had taken place. The main reason for their view is that accession is a form of original acquisition of ownership and, therefore, does not require the intention of the owner of the movable to transfer ownership. However, in our view the cases in which subjective intention was emphasised are not necessarily in conflict with the basic principles of property law, since the ob- jective factors were not conclusive of accession in those cases. According to the principles of inaedificatio , movables that have been permanently attached to land cease to exist as independent things and become part of the immovable object to which they are attached. 66 Conversely, if the independent identity of a movable is not lost and it is relatively easily removable from the land, it is not necessarily clear from the objective factors that accession indeed had taken place. To con- sider the subjective intention of the annexor in cases of that nature is therefore not necessarily a result of confusing the original with the derivative modes ac- quisition of property, unless (as one or two decisions indeed suggest) the court in fact emphasises the owner9s intention not to transfer ownership instead of the annexor9s intention not to attach permanently. It is only these decisions that in- deed confuse the two methods of acquisition and that therefore should be rejected.

It has to be said that the courts do sometimes conclude very easily that the objective factors are inconclusive. In cases such as Melcorp SA the manner and degree of attachment might not be decisive of accession (because the movable

62 Carey Miller 1984 SALJ 207; Breitenbach 1985 THRHR 464. 63 Carey Miller 1984 SALJ 207. 64 Van der Merwe <The law of property (including mortgage and pledge)= 1980 ASSAL 2323233. 65 Freedman 2000 SALJ 6733674; Van der Merwe 1980 ASSAL 2323233. 66 See 2 1 above.

INAEDIFICATIO : A CONSTITUTIONAL ANALYSIS 207

the property of another. The majority view was that, since the owner of the mov- able was not paid in full, he is regarded not to have intended to give up owner- ship. The majority view was sustained by the fact that it was not difficult to re- move the machinery in question from the land. One can conclude that the court in MacDonald refused to accept that accession had taken place because it elected to enforce a debt that was owed to the owner of the machine under a reservation of ownership.

Similarly, in Melcorp SA the court placed considerable weight on the annexor9s ipse dixit (in the hire-purchase contract) to arrive at the conclusion that the lifts remained movable until the purchase price was fully paid. Since the lifts were readily removable from the building (coupled with the fact that ownership of the lifts was reserved) the court held that the lifts remained movable. 69 Again, the court refused to accept that accession had taken place and instead elected to en- force the debt that was owed to the owner of the lifts. Since the lifts were readily removable, the court decided that accession had not occurred, despite the fact that the nature and object of the lifts indicated that the lifts were intended to be installed permanently in the building.

In Konstanz the court went even further and stated that the intention of the owner of the movable is not merely important, but in fact decisive. The court held that inaedificatio had not occurred because the hire-purchase contract indi- cated clearly that the respondent would remain the owner of the irrigation system until payment in full of the purchase price. 70 The court9s finding that the irriga- tion system did not become part of the land also protected the interests of the owner of the movables who reserved ownership as security for full payment of the purchase price.

The question is whether it is desirable to rely so heavily on the stated or actual intention of the owner of the movable when determining whether accession had taken place in cases of credit sales. At least in some instances, the court justifies its reliance on the intention of the owner of the movable in these cases by explic- itly stating that an owner of a movable should not be deprived of ownership without his consent. 71 However, since it is evident that the movable would be considered permanently attached to the land if the purchase price had been paid in full, one can argue that the real justification of the courts9 reliance on the in- tention of the owner of the movable in these instances is commercial policy, namely, to protect the real security interest embodied in the reservation of own- ership. In other words, the decision that accession had not occurred in cases where ownership of the movable is reserved subject to payment of the full pur- chase price is arguably a policy choice in favour of enforcing contractual debts in credit sales. Effective enforcement of contractual debts is said to be vital for the proper functioning of any market-based system, 72 and holding that accession had not occurred in cases of this kind would arguably promote commercial stability.

Therefore, if it is decided that accession is suspended by a reservation of own- ership for credit security, the landowner should either pay the amount due for the

69 See 2 3 above. 70 See 2 3 above. 71 MacDonald 467. 72 Brits Mortgage foreclosure under the Constitution: Property, housing and the National Credit Act (LLD thesis US 2012) 316.

208 2016 (79) THRHR

purchase of the movable or allow the seller to remove the movable from the land. This is an effective and justifiable way of debt enforcement and enforcing pay- ment for commercial policy reasons, as long as the movable is still reasonably easily removable from the land. The question is whether such a policy justifica- tion could withstand constitutional scrutiny.

5 CONSTITUTIONAL IMPLICATIONS

Accession decisions should be grounded in a constitutionally sound approach. Therefore, it is important to examine whether a decision taken for policy reasons that accession had not taken place, constitutes a deprivation of property that can pass muster in view of section 25 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996. In First National Bank of SA Ltd t/a Wesbank v Commissioner, South African Revenue Service; First National Bank of SA Ltd t/a Wesbank v Minister of Finance , 73 the Constitutional Court indicated that the starting point when considering any constitutional challenge under section 25 of the Constitu- tion must be section 25(1). Section 25(1) provides that no one may be deprived of property except in terms of law of general application, and that no law may permit arbitrary deprivation. To analyse the constitutional validity of a policy decision to protect the real security interests of credit grantors in case of a poten- tial conflict with the interests of landowners or third parties who might benefit from accession by building, we consider the methodology that the Constitutional Court developed in the FNB decision. Roux lists the guidelines that structure the FNB methodology as follows: <(a) Does that which is taken away from [the property holder] by the operation of [the law in question] amount to property for purposes of s 25? (b) Has there been a deprivation of such property by the [organ of state concerned]? (c) If there has, is such deprivation consistent with the provisions of s 25(1)? (d) If not, is such deprivation justified under s 36 of the Constitution? (e) If it is, does it amount to expropriation for purpose of s 25(2)? (f) If so, does the [expropriation] comply with the requirements of s 25(2)(a) and (b)? (g) If not, is the expropriation justified under s 36?= 74

The first question is whether the affected interest qualifies as property for consti- tutional purposes. Apart from providing in section 25(4)(b) that property is not limited to land, the Constitution does not give any definition of property, but the Constitutional Court has confirmed that corporeal movables and land are at the heart of the constitutional concept of property and must in principle be protected under section 25. 75 In addition, property may encompass a range of rights, ob- jects and interests in property. 76 In accession cases, it needs to be established

73 2002 4 SA 768 (CC) para 60. 74 Roux <Property= in Woolman et al (eds) Constitutional law of South Africa Vol 3 (OS 2003) 46-3. 75 FNB para 51. See also Transvaal Agricultural Union v Minister of Land Affairs 1996 12 BCLR 1573 (CC); Roux and Davis <Property= in Cheadle et al (eds) South African consti- tutional law: The Bill of Rights (RS 10 2011) 20-17. 76 Van der Walt Constitutional property law (2011) 192. See also National Credit Regulator v Opperman 2013 2 SA 1 (CC) (money debt); Agri South Africa v Minister for Minerals and Energy 2013 4 SA 1 (CC) (mineral rights); Shoprite Checkers (Pty) Limited v Member continued on next page

210 2016 (79) THRHR

case where the movable is subject to a credit sale with reservation of ownership, the owner of the movable can prove a deprivation of his property because he lost ownership of it when his movable ceased to exist as a result of permanently acceding to the land. In Unimark the court held that a certain canopy, steel gates, kitchen sink and floor tiles had become immovable as a result of accession. In this case, deprivation can be proved because the owner of the attached movables lost ownership of the movables that became permanently attached to the land, while the owner of the land now owns everything that is permanently attached to his land by accession. Therefore, it can be said that the principles of accession deprived the owner of his movables. If accession did in fact take place, the for- mer owner of the movables, therefore, can prove both that he had a property in- terest (ownership of movables) and that he was deprived of that property by the common law principles of accession.

It therefore seems that the constitutional issue of a deprivation of property can only be raised in cases where a court decides, either on the objective factors or on the subjective intention or on a combination of these, that a movable had permanently attached to land, that the movable had thereby ceased to exist as an independent object, and that ownership of the movable had been lost by opera- tion of law. In cases of this kind, once it has been established that there was accession and that a deprivation of property had taken place, step (c) in the FNB methodology is to ask whether the deprivation of property that had taken place in terms of the principles of accession is in line with section 25(1). This section contains two formal requirements for the deprivation of property. Firstly, the deprivation must have been authorised by law of general application. Since the principles of the common law qualify as law of general application, 78 a decision that ownership of movables had been lost on the basis of the common law prin- ciples of accession would satisfy this first requirement. The second requirement in section 25(1) is that no law may permit arbitrary deprivation of property. According to Van der Walt, it would be difficult, but not impossible to prove that a deprivation authorised by common law principles constitutes arbitrary depriva- tion. 79 Nonetheless, in a case of inaedificatio the principles that regulate acces- sion may in principle not permit deprivation of property that is arbitrary. In accordance with the conclusions in the preceding paragraphs, this analysis will only arise in accession cases where it has been established that accession did take place and that the former owner of the movables had lost ownership when the movables became permanently attached to land and thus lost their independent existence as objects of property rights.

According to the FNB decision, a deprivation is arbitrary if the law that autho- rises the deprivation does not provide sufficient reason for the particular depriva- tion in question or is procedurally unfair. 80 Therefore, if the court decides that a movable no longer exists independently because accession had occurred and that its removal from the land would cause damage to the land or the movable, that should be sufficient reason for holding that the deprivation was not arbitrary. On this basis a deprivation in the form of loss of ownership of a movable that has become permanently attached to land generally would not be arbitrary if the

78 218. 79 2343235. 80 FNB para 100.

INAEDIFICATIO : A CONSTITUTIONAL ANALYSIS 211

court holds that accession had occurred according to the normal common law principles. It has been argued that in cases where loss of ownership of the mov- able seems unfair, the prejudiced owner of the movable might have an action for compensation against the landowner based on unjustified enrichment. 81 This possibility would strengthen the case for deciding that a deprivation caused by accession generally is not arbitrary.

The question whether accession results in an expropriation in terms of step (e) of the FNB methodology arguably would never arise in a case of accession be- cause there is no common law authority for expropriation in South African law. The authority to expropriate derives exclusively from statute. 82 Therefore, loss of property by operation of the principles of common law should generally never raise an expropriation issue in South African law. If property is compulsorily <transferred= from one person to another by operation of law in terms of a com- mon law principle such as the rules of accession, that <transfer= does not qualify as an expropriation that activates section 25(2) or 25(3).

6 CONCLUSION

Determining whether a movable has attached to land permanently is sometimes controversial. It has been said that the courts have moved away from the so- called traditional approach to a so-called new approach, but the case law indi- cates that the proof of such a shift is less clear-cut than it seems. Both older cases (associated with the traditional approach) and later cases (associated with the new approach) emphasise the intention of the owner of the movables to establish whether accession had occurred, particularly when the objective factors (nature of the movable and the manner of attachment) are inconclusive. It is true, how- ever, that a small number of cases go further and consider the intention of the owner of the movable not to transfer ownership as a decisive factor, even in in- stances where the owner was not the annexor. Interestingly, a line of both older and recent cases dealing with movables that are subject to instalment sale agree- ments seem to emphasise the intention of the owner of the movable for commer- cial policy reasons, specifically to protect ownership of the movables in cases where ownership had been reserved in a credit sale contract.

In view of the FNB methodology, these cases and the policy grounds on which they favour the interests of credit grantors over the interests of landowners (and their creditors) who might stand to benefit from accession should never inspire a constitutional challenge on the basis of section 25 of the Constitution, because the affected landowners had never acquired a property interest that can be pro- tected in terms of section 25. In cases where the courts decide that accession in fact had occurred, it should generally be possible to establish that the former owner of the affected movable had a protected property interest for purposes of section 25 and that it had been deprived of that property for purposes of sec- tion 25(1). However, the deprivation generally would not be arbitrary since there

81 Badenhorst et al 154. 82 Harvey v Umhlatuze Municipality 2011 1 SA 601 (KZP) para 81. See Van der Walt Consti- tutional property law 346 453; Van der Walt <Replacing property rules with liability rules: Encroachment by building= 2009 SALJ 622; Gildenhuys Onteieningsreg (2001) 10 93. See also Van der Walt Property in the margins (2009) 2003201; Temmers Building encroach- ments and compulsory transfer of ownership (LLD thesis US 2010) 1723173.

AJ Van der Walt & NL Sono The law regarding inaedificatio A constitutional analysis (2016 )

Course: Property Law

University: University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

Students also viewed

- Shoprite Checkers (Pty) Limited v Member of the Executive Council for Economic Development, Environmental Affairs And Tourism, Eastern Cape and Others 2015 (6) SA 125 (CC)

- Chapters 15 - 17 - termination of possession, intro to other types of limited real rights, and servitudes and restrictive covenants

- Ownership in property law and case summary

- March notes prop law - land restitution

- Topic 15 REAL Security - Lecture notes 15

- Ngcukaitobi Bishop Article ( Final) for the expropriation