In 2022, I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. With luck, we’ll get to #1 in December. Enjoy!

* * *

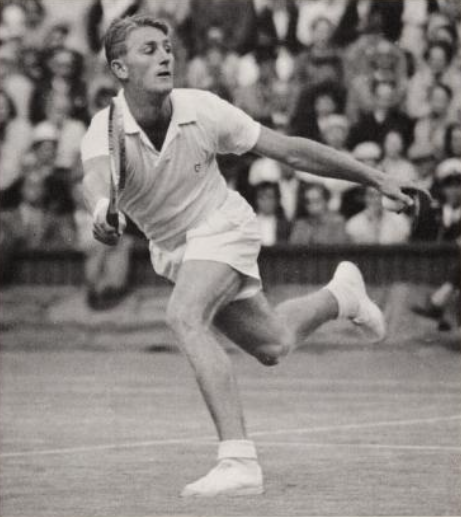

Lew Hoad [AUS]Born: 23 November 1934

Died: 3 July 1994

Career: 1950-72

Played: Right-handed (one-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 1 (1953)

Major singles titles: 4

Total singles titles: 52

* * *

Tennis’s GOAT debate will never be resolved, even if Rafael Nadal wins another ten majors. There are just too many different ways to define “greatest of all time.” Are we looking for the longest span of sustained excellence? The most untouchable peak? Some particular combination of the two?

Many fans prefer the all-time grand slam count, which is essentially a vote for longevity over a shorter peak, no matter how brilliant. The Tennis 128 ranks players by a combination of the two. Many former players, however, tend to recall the best tennis they ever saw in person, often because they were right across the net, on the losing end of it.

One 1950s-era Australian player said, “[W]hen you play [Lew] Hoad, it’s like you’re not even there.”

My friend Charles Friesen tracks GOAT claims over the years from any source he can find–books, magazine articles, forum posts, broadcasts, and more–where a player or expert has offered a their personal list of the best of all time. In Charles’s tally, 17 different men have gotten at least one number-one vote, from William Renshaw back in 1890 to Novak Djokovic last year. Only eight of those players have been named five times or more.

Charles has found eight votes for Hoad, submitted from the 1980s to the early 2010s. More than Richard “Pancho” González, more than John McEnroe, more than Pete Sampras, even more than Djokovic–at least so far.

González never went on record with a GOAT pick of his own. Still, he made a good case for the rival he faced nearly 200 times:

Hoad was the only guy who, if I was playing my best tennis, could still beat me. I think his game was the best ever, better than mine. He was capable of making more shots than anybody. His two volleys were great. His overhead was enormous. He had the most natural tennis mind with the most natural tennis physique.

González summed it up: “If there was ever a Universe Davis Cup, and I had to pick one man to represent Planet Earth, I would pick Lew Hoad in his prime.”

* * *

Had Hoad ever gone off to represent his planet in a one-match battle for galactic domination, us earthlings would’ve had plenty of reason to be nervous. The Australian’s career record doesn’t match his imposing reputation because, well, he often wasn’t that imposing.

Jack Kramer, who would spend two years trying to convince Hoad to join his professional troupe, had recognized Hoad’s talent as early as 1946. Kramer and Ted Schroeder were in Australia to compete for the Davis Cup, and they saw the 12-year-old Lew play an exhibition against Ken Rosewall, who was three weeks older. Hoad lost badly–as he usually did against Rosewall in those days–but his raw shotmaking ability was already evident.

Kramer was one of many figures in Hoad’s life who would try to round out his game and help the young man become more consistent. Some of the coaching worked, but most of the efforts on the mental side of things didn’t. Even when Kramer offered cash bonuses for winning matches–on top of the $125,000 Hoad received for turning pro–you never quite knew which Lew would show up.

In the final reckoning, Kramer was a bit harsh on his golden boy. He called Hoad “overrated,” and “the most inconsistent of all the top players.” The promoter even had an explanation for the rosier assessments from others: “[H]e is held in greater esteem than he deserves, I think, because he was so damn popular with everyone that people in tennis wanted to believe he was better.”

Rod Laver was definitely one of those people. Rocket Rod was four years younger than Hoad, exactly the right age difference to make Lew his idol for life. Laver loved his “majestic” game, and he sought to emulate Hoad’s friendly, generous personality. Lew didn’t go in for gamesmanship, and like his mentor Harry Hopman, he barely had any tactics.

Much as he admired Hoad, Laver recognized the man’s shortcomings. “Lew could be lackadaisical in preliminary matches or in minor tournaments, and was knocked out by blokes not fit to tie his shoelaces.” Especially early in his career, he struggled to focus on court. For years, Rosewall–as intense as Lew was casual–didn’t like to play doubles with him because he was so easily distracted.

Laver only played Hoad after they had both turned pro, when injuries had limited the older man’s game. Still, Laver claimed that “an on-song Hoad was the best player I ever played against.” Some sources drive home the point by saying that Hoad usually won. In fact, Laver won 34 of the 60 meetings I’ve found records for. Because those matches came at the tail end of Hoad’s career, they don’t tell us much about his greatness. But they do serve as a reminder that memory is tricky. For every one match Hoad played that left his peers with their jaws on the floor, there was another when he inexplicably lost a set or just couldn’t find the range with his groundstrokes.

* * *

When everything was going right, Hoad did indeed play some of the best tennis in history. His last match as an amateur was the 1957 Wimbledon final against countryman Ashley Cooper. He gave Cooper a 6-2, 6-1, 6-2 beatdown in less than an hour, winning more than one-third of the points with aces or clean winners. The London Daily Express called it “Murder on Centre Court.”

Nicola Pietrangeli lost all eight sets he played against Lew. “For one match he was unbeatable. He could do anything.”

Mal Anderson, an Australian who took advantage of Hoad’s absence to win the 1957 US National Championships, never missed a chance to see Hoad and González play. “It was unbelievable tennis. We … were like beginners compared to them.”

Art Larsen, the eccentric American who won at Forest Hills in 1950, said that Lew served harder than Andy Roddick. “He was the best I’ve seen.”

When Kramer wasn’t driven to distraction by Hoad’s inconsistency, he sat back in awe:

I’d marvel at the shots he could think of. He was the only player I ever saw who could stand six or seven feet behind the baseline and snap the ball back hard, crosscourt. He’d try for winners off everything, off great serves, off tricky short balls, off low volleys. … He could flick deep topspin shots with his wrist that González couldn’t believe a human being could hit.

Like all the Australians of his era, Hoad was well-trained in doubles tactics. Yet he had the self-belief to throw them away with the match on the line. In the 1955 Davis Cup Challenge Round, he partnered Rex Hartwig against Tony Trabert and Vic Seixas of the United States. Lew served at 5-all in the deciding fifth set, and the Americans reached break point. In the ad court, the proper serve would’ve been a conservative kicker out wide to open up the court.

Instead, Hoad went big. He hit it flat at full speed, and Trabert could barely make contact. Twice more, the Americans earned a break point, and twice more, Lew gambled with the cannonball. The Aussies held. They took the match 7-5, secured the 1955 championship, and wouldn’t give back the Davis Cup for three more years.

Hoad (right) with Hartwig and Hopman. Ironically, Hoad considered Hartwig to be a streaky, unpredictable player without precedent: “I reckon it is safe to say that there will never be another like him. He has patches of eight or nine games in which his tennis is so breathtakingly brilliant nobody in the world, amateur or professional, can hope to cope with him.”

Six years later, Hoad and Trabert faced off in the deciding rubber of the Kramer Cup, the fledging pro equivalent of the Davis Cup. Lew was as brilliant in that match as he had been as an amateur. Trabert could only say, “Trying to stop Lew … was like fighting a machine gun with a rubber knife.”

* * *

The only things that could stop Lew were his own mind and, all too often, his body.

His first major breakthrough came in 1953, a year in which he won eight titles, six of them with victories against Rosewall in the semi-finals or final. He failed to make an impact at the majors, losing to Seixas both in the quarter-finals at Wimbledon and the semis at Forest Hills. Hoad got his revenge on Seixas in the Davis Cup Challenge Round, and that was just the beginning.

The Australians were going for their fourth consecutive Davis Cup title. But with the stalwart Frank Sedgman lost to the pro game, they had to rely on “two babes and a fox”–19-year-olds Hoad and Rosewall, coached by the ever-present Harry Hopman. Hoad kicked things off with a straight-set victory against Seixas, and Trabert–fresh off his first major title at Forest Hills–brushed aside Rosewall. The Americans won the doubles rubber as well, making quick work of Hoad and Hartwig.

Lew needed to beat Trabert to keep his country’s hopes alive. In front of 17,000 fans, the 19-year-old delivered one of the most memorable matches in Cup history. Trabert wasn’t as flashy as the Australian, but he played Kramer-style “Big Game” tennis that aimed to keep Hoad on the back foot. Neither man had a tactical lob to speak of, so the result was non-stop aggression, each man looking for the slightest opening to come forward.

Hoad built a 13-11, 6-3 lead, but in a drizzle, on a slippery grass court, he lost the next two sets. Hopman’s craftiness may have been the difference. When Hoad slipped and fell in the fifth set, his coach teased him (something like, “Get up, you lazy bastard,” though recollections differ) to defuse the tension. As the match got even tighter, Hopman slipped him a dry racket when Trabert wasn’t looking. Hoad won, 7-5 in the fifth, and Rosewall sealed the deal with a four-set win over Seixas.

Lew’s performance in the Challenge Round was so impressive that some journalists rated him the number one player in the world, an honor almost never given to someone without a single major to his name. Unfortunately, it would take him a few years to live up to the acclaim.

Immediately after his Davis Cup heroics, Hoad was called up for national service. He missed the 1954 Australian Championships, and in training, he suffered a spider bite that was initially misdiagnosed and left him in a coma for two days. He returned to the tennis grind after his three-month stint in the army, but it took some time before he was back at full strength.

In 1955, Lew reached his first major final at home in Australia, where he lost to Rosewall in straight sets. Except for a Wimbledon doubles title with Hartwig, the rest of the season was a forgettable one. Hoad had even more reason than usual to be distracted: He was courting fellow player Jenny Staley. After they learned she was pregnant, they got married in a secret ceremony just before Wimbledon began. The press, especially in Australia, had been relentless in their speculation about the couple, and it showed in Lew’s on-court performance.

* * *

Back in shape, happily married, the press at bay, and with a baby due soon, Hoad finally showed the world what he was capable of. In 1956, he won 13 titles, including the first three legs of the Grand Slam. He beat Rosewall for the Australian and Wimbledon titles, and took the French title from Sven Davidson despite spending the night before the final splitting a bottle of vodka with a Russian diplomat.

The Wimbledon final was Lew at his best. He took a two-sets-to-one lead over Rosewall but fell behind, 4-1, in the fourth. Recognizing that his longtime rival could quickly take away the set and the match, he sprung into action. Modest as he was, even Hoad couldn’t deny that he had achieved perfection:

Of the last 23 points, I won 20, 14 of them from outright winners, five with aces, and in the fifteen minutes we took for the last five games the ball did not once land where I did not intend it to go, and I did not make a single tactical mistake.

Hoad barely had a chance to bask in his success before a new problem presented itself. He developed back spasms so severe that he opted to spend a week sailing across the Atlantic rather than subject himself to a cramped airplane seat. The pain would come and go, but it would be two decades before he found a doctor who knew what to do about it. The first specialist he saw told him that he needed more exercise.

When Forest Hills came along two months later, Lew had begun to learn how to manage his back, and he reached the final. He met Rosewall once again. On a gusty day, his steady, intense countryman better handled the conditions. Rosewall won in four sets, and it seemed to Lew that his old friend was more disappointed at the Grand Slam near-miss than Hoad was himself. He didn’t blame his back, but it must have been a factor.

The injury didn’t improve, and he spent several weeks in early 1957 immobilized in a plaster cast. He recovered in time to play only a handful of events before Wimbledon, but the abbreviated preparation didn’t hurt him. He worked his way into form throughout the fortnight, facing his only real challenge in a quarter-final battle with countryman Mervyn Rose. He played the best match of his life in the final, leaving Ashley Cooper in the dust.

Then, at age 22, for a signing bonus of $125,000, Lew Hoad turned pro.

* * *

Hoad had always been a work in progress. Even when he beat Trabert in the 1953 Davis Cup Challenge Round, he had little in the way of groundstrokes, a glaring hole in his game that had allowed Rosewall to beat him since they were 12 years old. Hopman split up the Hoad-Rosewall doubles team so that Lew would be forced to play the left court beside Rex Hartwig. The unfamiliar side gave him some much-needed backhand practice.

It sure seemed to work. The more well-rounded Hoad won four of his last five singles majors as an amateur. But Jack Kramer signed him to be the next big professional star, and that meant he would need to hold his own with Richard González. The pro game, with its relentless schedule of one-night stands, was more physically demanding than the amateur tour. The temporary indoor surfaces that served for so many pro matches were unfamiliar to amateurs, while experienced pros like González spent years adapting to them. Most players, no matter how talented, struggled to make the transition.

Kramer knew that Hoad would struggle more than most. His casual approach to the game would clash with the rigors of the pro circuit, and on the technical side of things, he needed more work on his defensive skills. Kramer designed Lew’s first several months as a sort of boot camp. Pancho Segura taught him how to hit a proper lob, and the new star was, for the most part, kept away from González.

It all sounds a bit like pro boxing because, well, it was. The Hoad-González duel–the challenger versus the champion–wasn’t a one-night-only showcase in Las Vegas, but it was the biggest drawing card in pro tennis. Kramer needed to build it up as an arena-filling attraction, and he had to make sure it would live up to the billing.

For a few months, Hoad-versus-González was everything Kramer had hoped for. González didn’t like the way Kramer had kept the challenger away from him in late 1957, but there was nothing he could do about it, just as there was little he could do to stop the young Australian’s power game. The two men were slated to play up to 100 matches to decide the new champion; Hoad got off to an early 8-5 lead, and then built up an 18-9 advantage.

But then, on a chilly night in Southern California, in front of a packed house full of celebrities, Lew’s back seized up again. He never really recovered. For the remainder of the tour, he could barely tie his own shoelaces. González would say he used “every trick I ever learned” and “a maximum of determination” to overcome his compromised foe. The champion came back from his early deficit and won the series from Hoad, 51 matches to 36.

* * *

Hoad continued playing professional tennis for a decade, winning another three dozen matches against González and nearly holding his own against the younger, healthier Laver. He entered Wimbledon a few times after Open tennis became a reality in 1968, though by that point, he was no longer fully committed to tennis. His back wouldn’t have allowed it, anyway.

It wasn’t until 1978 that his back problems were properly diagnosed and treated. He had played more than a decade of professional tennis with two ruptured discs. The doctor who operated on him couldn’t fathom how Lew had continued to compete–or even walk, for that matter.

When he was healthy and focused, Hoad had an effect on spectators–and opponents–much like that of Roger Federer at his peak. The effortless power, the improvised winners–the type of tennis that takes years of practice but somehow looks entirely inborn.

The Australian legends who once considered Hoad to be the greatest of all time seem to have moved on. Laver and Rosewall, in particular, once put Lew atop their lists. They’ve since gone on record for Roger. Perhaps now, in a hypothetical battle for the fate of the universe, peak Federer will play for Earth. Still, Lew Hoad should suit up as first alternate.