'Underemployed': The TV Show That Nails How the Recession Changed Sex

Halfway through its first season, MTV's new sitcom has smartly centered on a tough truth for Millenials: What happens in the economy affects what happens in the bedroom.

"I don't know how we're ever going to pay for her college," frets Lou, one of the broke 20-somethings at the center of MTV's new show Underemployed. His girlfriend Raviva, a self-righteous, bohemian, would-be singer who has just given birth to their unplanned baby girl, responds, "I don't know how we're gonna finish paying for ours."

As that quippy exchange suggests, Underemployed is the latest comedy to capitalize on the strapped-Millennial zeitgeist, alongside the cartoonish 2 Broke Girls, the quirkier and more naturalistic Girls, the frenetic Shameless, and the upcoming F*ck I'm In My 20s. Like those shows, Underemployed has flaws: Its zingers can be on-the-nose, its characters are painted with overly broad strokes, and it suffers from Impossibly Gigantic Urban Apartment syndrome. But in the first half of its first season, it has crystallized a recession-era truism more effectively than any of its peers: The economy is personal. It's in your bedroom and your living room, whether you like it or not.

In other shows portraying the young and the penniless, sex is a welcome respite from economic angst, and friendships mostly exist in a bubble separate from finances. In Girls, Hannah's love life has little correlation with her money woes. In Shameless, most of Fiona's romantic exploits are tinged with an urge to screw the pain away, to forget poverty for just a few sweaty minutes. But in Underemployed, sexual and personal decisions have economic consequences. The show reaches for old dramatic tropes—a tryst with the boss, baby-mama drama, showbiz's corrosive whoring—and infuses them with post-crisis gravitas.

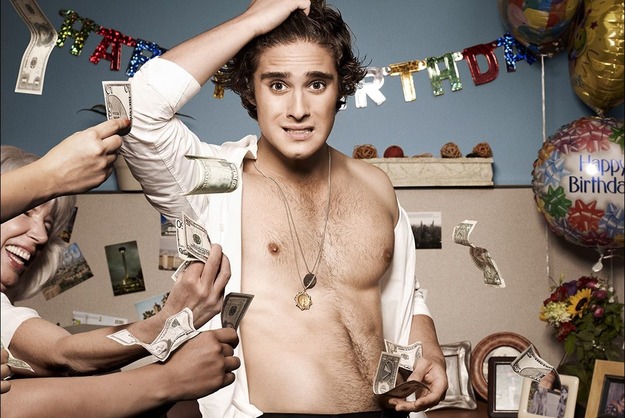

Aspiring actor-model Miles's survival would hinge on his sex appeal in any era, but during a downturn, the need to lean on his looks becomes all the more mandatory. In the first episode, he sleeps with a "hot cougar" in order to meet Calvin Klein at a cocktail party, only to discover that his sole function at the event is to serve mojitos. Then, in order to snag a role as a spokesman for a mid-grade tequila (which, incidentally, his friend Daphne's advertising firm represents), Miles has to flash his bedroom eyes at another older woman to seal the deal. He laughs it all off with a dippy demeanor, but there's a strain of unease and ickiness every time he trades his sexuality for a meal ticket.

The cutthroat sexual economy looms even larger in Daphne's storyline, which takes her from unpaid intern to $750 a week at her advertising agency. She only scores a salary after guilt-tripping (or is it blackmailing?) her boss, with whom she has just had sex in the office's parking garage despite the fact that he has a girlfriend. Later, both she and Miles, now the face of Madura tequila, have to delicately dodge a horny client who wants to bed them both. They achieve this by sheer luck: The client, drunk on his own tequila, passes out with his pants around his ankles at just the right moment.

Sofia is a pluckier version of Girls' Hannah, our resident overeducated service worker and struggling writer (every night she attempts to works on her novel for a few minutes, then plays Angry Birds on her phone). She earns minimum wage at Donut Girl, where she is made to wear a humiliating hat and scrub ravaged toilets. Her professional arc is underdeveloped; instead of showing the very real drudgery that accompanies service jobs, Underemployed expects us to feel sorry for her when her manager prohibits laptops. But her personal life, the most fleshed-out of all the characters', is profoundly affected by her economic circumstances. When she drops her phone in the toilet, her much richer girlfriend blithely buys her a new one, creating an irreparable wedge that ultimately sours their relationship. And unlike her relatively privileged friends, Sofia's homophobic parents have cut her off financially because she is gay, providing yet another reminder that one's sexuality can be a liability in a precarious, part-time economy.

And then there's that baby. In most non-premium cable TV shows, babies are mere props that never seem to interfere with its parents' lives. Here, in a fascinating twist, Lou and Raviva's kid becomes the nucleus of the show, inspiring a kind of utopian child-rearing community—and, implicitly, a rejection of the drowning nuclear family.

"If and when any of us have kids, and we need help, we'll just light the ultimate bat signal," blurts Daphne, after a frenetic montage of a collaborative diaper-change. "And no matter what we're doing, we'll just drop it and help each other. That would be so much better than the way we were raised."

The entire gang is present for Daphne's declaration, and everyone solemnly agrees. By the end of the episode, the bat signal has been lit, and the group has assembled a crib, acquired gently distressed baby clothes, and procured a four-track for Raviva, lest she sacrifice her singing dreams for motherhood. A few episodes later, the karma comes back: Sofia, on the brink of being evicted after she impulsively quits her job at Donut Girl to free up time to pen her novel, is offered baby Rosemary's room in Lou and Raviva's loft. She'll live rent-free as long as she babysits for them—which is actually a pretty brilliant idea. Each episode ends a little too pat, but the message is surprisingly fresh: Things don't have to be this way. Parenthood doesn't have to be isolating. Our intellectual lives don't have to be suffocated by low-wage jobs. And sex doesn't have to be our currency when traditional outlets of upward mobility have failed us.

Of course, the show's idealism also functions as the same lacquer that allows most mainstream TV to spare viewers the true ugliness of an increasingly unstable economy—instead favoring sunny solutions that don't require institutional change. Ultimately, Underemployed serves as a less messy, less cynical version of Teen Mom, another MTV show deftly linking our libidos with our wallets. The network's devout teen viewers have been duly warned: The stakes of sex—and all our personal decisions—have never been higher.