The Literature of Exhaustion

“By ‘exhaustion’ I don’t mean anything so tired as the subject of physical, moral, or intellectual decadence, only the used-upness of certain forms or exhaustion of certain possibilities — by no means necessarily a cause for despair.”

I WANT to discuss three things more or less together: first, some old questions raised by the new intermedia arts; second, some aspects of the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges, whom I greatly admire; third, some professional concerns of my own, related to these other matters and having to do with what I’m calling “the literature of exhausted possibility” — or, more chicly, “the literature of exhaustion.”

By “exhaustion” I don’t mean anything so tired as the subject of physical, moral, or intellectual decadence, only the used-upness of certain forms or exhaustion of certain possibilities — by no means necessarily a cause for despair. That a great many Western artists for a great many years have quarreled with received definitions of artistic media, genres, and forms goes without saying: pop art, dramatic and musical “happenings,” the whole range of “intermedia” or “mixed-means” art, bear recentest witness to the tradition of rebelling against Tradition. A catalogue I received some time ago in the mail, for example, advertises such items as Robert Filliou’s Ample Food for Stupid Thought, a box full of postcards on which are inscribed “apparently meaningless questions,” to be mailed to whomever the purchaser judges them suited for; Ray Johnson’s Paper Snake, a collection of whimsical writings, “often pointed,” once mailed to various friends (what the catalogue describes as The New York Correspondence School of Literature); and Daniel Spoerri’s Anecdoted Typography of Chance, “on the surface” a description of all the objects that happen to be on the author’s parlor table — “in fact, however … a cosmology of Spoerri’s existence.”

“On the surface,” at least, the document listing these items is a catalogue of The Something Else Press, a swinging outfit. “In fact, however,” it may be one of their offerings, for all I know: The New York Direct-Mail Advertising School of Literature. In any case, their wares are lively to read about, and make for interesting conversation in fiction-writing classes, for example, where we discuss Somebody-or-other’s unbound, unpaginated, randomly assembled novel-in-a-box and the desirability of printing Finnegans Wake on a very long roller-towel. It’s easier and sociabler to talk technique than it is to make art, and the area of “happenings” and their kin is mainly a way of discussing aesthetics, really; illustrating “dramatically” more or less valid and interesting points about the nature of art and the definition of its terms and genres.

One conspicuous thing, for example, about the “intermedia” arts is their tendency (noted even by Life magazine) to eliminate not only the traditional audience — “those who apprehend the artist’s art” (in “happenings” the audience is often the “cast,” as in “environments,” and some of the new music isn’t intended to be performed at all) — but also the most traditional notion of the artist: the Aristotelian conscious agent who achieves with technique and cunning the artistic effect; in other words, one endowed with uncommon talent, who has moreover developed and disciplined that endowment into virtuosity. It’s an aristocratic notion on the face of it, which the democratic West seems eager to have done with; not only the “omniscient” author of older fiction, but the very idea of the controlling artist, has been condemned as politically reactionary, even fascist.

I suppose the distinction is between things worth remarking — preferably over beer, if one’s of my generation — and things worth doing. “Somebody ought to make a novel with scenes that pop up, like the old children’s books,” one says, with the implication that one isn’t going to bother doing it oneself.

However, art and its forms and techniques live in history and certainly do change. I sympathize with a remark attributed to Saul Bellow, that to be technically up to date is the least important attribute of a writer, though I would have to add that this least important attribute may be nevertheless essential. In any case, to be technically out of date is likely to be a genuine defect: Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony or the Chartres Cathedral if executed today would be merely embarrassing. A good many current novelists write turn-of-the-century-type novels, only in more or less mid-twentieth-century language and about contemporary people and topics; this makes them considerably less interesting (to me) than excellent writers who are also technically contemporary: Joyce and Kafka, for instance, in their time, and in ours, Samuel Beckett and Jorge Luis Borges. The intermedia arts, I’d say, tend to be intermediary too, between the traditional realms of aesthetics on the one hand and artistic creation on the other; I think the wise artist and civilian will regard them with quite the kind and degree of seriousness with which he regards good shoptalk: he’ll listen carefully, if noncommittally, and keep an eye on his intermedia colleagues, if only the corner of his eye. They may very possibly suggest something usable in the making or understanding of genuine works of contemporary art.

THE man I want to discuss a little here, Jorge Luis Borges, illustrates well the difference between a technically old-fashioned artist, a technically up-to-date civilian, and a technically up-to-date artist. In the first category I’d locate all those novelists who for better or worse write not as if the twentieth century didn’t exist, but as if the great writers of the last sixty years or so hadn’t existed (nota bene that our century’s more than two-thirds done; it’s dismaying to see so many of our writers following Dostoevsky or Tolstoy or Flaubert or Balzac, when the real technical question seems to me to be how to succeed not even Joyce and Kafka, but those who’ve succeeded Joyce and Kafka and are now in the evenings of their own careers). In the second category are such folk as an artist neighbor of mine in Buffalo who fashions dead Winnies-the-Pooh in sometimes monumental scale out of oilcloth stuffed with sand and impaled on stakes or hung by the neck. In the third belong the few people whose artistic thinking is as hip as any French new-novelist’s, but who manage nonetheless to speak eloquently and memorably to our still-human hearts and conditions, as the great artists have always done. Of these, two of the finest living specimens that I know of are Beckett and Borges, just about the only contemporaries of my reading acquaintance mentionable with the “old masters” of twentieth-century fiction. In the unexciting history of literary awards, the 1961 International Publishers’ Prize, shared by Beckett and Borges, is a happy exception indeed.

One of the modern things about these two is that in an age of ultimacies and “final solutions” — at least felt ultimacies, in everything from weaponry to theology, the celebrated dehumanization of society, and the history of the novel — their work in separate ways reflects and deals with ultimacy, both technically and thematically, as, for example, Finnegans Wake does in its different manner. One notices, by the way, for whatever its symptomatic worth, that Joyce was virtually blind at the end, Borges is literally so, and Beckett has become virtually mute, musewise, having progressed from marvelously constructed English sentences through terser and terser French ones to the unsyntactical, unpunctuated prose of Comment C’est and “ultimately” to wordless mimes. One might extrapolate a theoretical course for Beckett: language, after all, consists of silence as well as sound, and the mime is still communication — “that nineteenth-century idea,” a Yale student once snarled at me — but by the language of action. But the language of action consists of rest as well as movement, and so in the context of Beckett’s progress immobile, silent figures still aren’t altogether ultimate. How about an empty, silent stage, then, or blank pages1 — a “happening” where nothing happens, like Cage’s 4′ 33″ performed in an empty hall? But dramatic communication consists of the absence as well as the presence of the actors; “we have our exits and our entrances”; and so even that would be imperfectly ultimate in Beckett’s case. Nothing at all, then, I suppose: but Nothingness is necessarily and inextricably the background against which Being et cetera; for Beckett, at this point in his career, to cease to create altogether would be fairly meaningful: his crowning work, his “last word.” What a convenient corner to paint yourself into! “And now I shall finish,” the valet Arsene says in Watt, “and you will hear my voice no more.” Only the silence Molloy speaks of, “of which the universe is made.”

After which, I add on behalf of the rest of us, it might be conceivable to rediscover validly the artifices of language and literature—such far-out notions as grammar, punctuation … even characterization! Even plot! — if one goes about it the right way, aware of what one’s predecessors have been up to.

Now J. L. Borges is perfectly aware of all these things. Back in the great decades of literary experimentalism he was associated with Prisma, a “muralist” magazine that published its pages on walls and billboards; his later Labyrinths and Ficciones not only anticipate the farthest-out ideas of The Something-Else Press crowd — not a difficult thing to do — but being marvelous works of art as well, illustrate in a simple way the difference between the fact of aesthetic ultimacies and their artistic use. What it comes to is that an artist doesn’t merely exemplify an ultimacy; he employs it.

Consider Borges’ story “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote”: the hero, an utterly sophisticated turn-of-the-century French Symbolist, by an astounding effort of imagination, produces — not copies or imitates, mind, but composes — several chapters of Cervantes’ novel.

It is a revelation [Borges’ narrator tells us] to compare Menard’s Don Quixote with Cervantes’. The latter. for example, wrote (part one, chapter nine):

… truth, whose mother is history, rival of time, depository of deeds, witness of tlte past, exemplar and adviser to the present, the future’s counselor.

Written in the seventeenth century, written by the “lay genius" Cervantes, this enumeration is a mere rhetorical praise of history. Menard, on the other hand, writes:

… truth, whose mother is history, rival of time, depository of deeds, witness of the past, exemplar and adviser to the present, the future’s counselor.

History, the mother of truth: the idea is astounding. Menard, a contemporary of William James, does not define history as an inquiry into reality but as its origin ….

Et cetera. Now, this is an interesting idea, of considerable intellectual validity. I mentioned earlier that if Beethoven’s Sixth were composed today, it would be an embarrassment; but clearly it wouldn’t be, necessarily, if done with ironic intent by a composer quite aware of where we’ve been and where we are. It would have then potentially, for better or worse, the kind of significance of Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup ads, the difference being that in the former case a work of art is being reproduced instead of a work of non-art, and the ironic comment would therefore be more directly on the genre and history of the art than on the state of the culture. In fact, of course, to make the valid intellectual point one needn’t even recompose the Sixth Symphony, any more than Menard really needed to re-create the Quixote. It would’ve been sufficient for Menard to have attributed the novel to himself in order to have a new work of art, from the intellectual point of view. Indeed, in several stories Borges plays with this very idea, and I can readily imagine Beckett’s next novel, for example, as Tom Jones, just as Nabokov’s last was that multivolume annotated translation of Pushkin. I myself have always aspired to write Burton’s version of The 1001 Nights, complete with appendices and tile like, in twelve volumes, and for intellectual purposes I needn’t even write it. What evenings we might spend (over beer) discussing Saarinen’s Parthenon, D. H. Lawrence’s Wuthering Heights, or the Johnson Administration by Robert Rauschenberg!

The idea, I say, is intellectually serious, as are Borges’ other characteristic ideas, most of a metaphysical rather than an aesthetic nature. But the important thing to observe is that Borges doesn’t attribute the Quixote to himself, much less recompose it like Pierre Menard; instead, he writes a remarkable and original work of literature, the implicit theme of which is the difficulty, perhaps the unnecessity, of writing original works of literature. His artistic victory, if you like, is that he confronts an intellectual dead end and employs it against itself to accomplish new human work. If this corresponds to what mystics do — “every moment leaping into the infinite,” Kierkegaard says, “and every moment falling surely back into the finite” — it’s only one more aspect of that old analogy. In homelier terms, it’s a matter of every moment throwing out the bath water without for a moment losing the baby.

ANOTHER way of describing Borges’ accomplishment is in a pair of his own favorite terms, algebra and fire. In his most often anthologized story, “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius,” he imagines an entirely hypothetical world, the invention of a secret society of scholars who elaborate its every aspect in a surreptitious encyclopedia. This First Encyclopaedia of Tlön (what hedonist would not wish to have dreamed up the Britannica?) describes a coherent alternative to this world complete in every respect from its algebra to its fire, Borges tells us, and of such imaginative power that, once conceived, it begins to obtrude itself into and eventually to supplant our prior reality. My point is that neither the algebra nor the fire, metaphorically speaking, could achieve this result without the other. Borges’ algebra is what I’m considering here — algebra is easier to talk about than fire — but any intellectual giant could equal it. The imaginary authors of the First Encyclopaedia of Tlön itself are not artists, though their work is in a manner of speaking fictional and would find a ready publisher in New York nowadays. The author of the story “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius,” who merely alludes to the fascinating Encyclopaedia, is an artist; what makes him one of the first rank, like Kafka, is the combination of that intellectually profound vision with great human insight, poetic power, and consummate mastery of his means, a definition which would have gone without saying, I suppose, in any century but ours.

Not long ago, incidentally, in a footnote to a scholarly edition of Sir Thomas Browne (The Urn Burial, I believe it was), I came upon a perfect Borges datum, reminiscent of Tlön’s self-realization: the actual case of a book called The Three Impostors, alluded to in Browne’s Religio Medici among other places. The Three Impostors is a nonexistent blasphemous treatise against Moses, Christ, and Mohammed, which in the seventeenth century was widely held to exist, or to have once existed. Commentators attributed it variously to Boccaccio, Pietro Aretino, Giordano Bruno, and Tommaso Campanella, and though no one, Browne included, had ever seen a copy of it, it was frequently cited, refuted, railed against, and generally discussed as if everyone had read it — until, sure enough, in the eighteenth century a spurious work appeared with a forged date of 1598 and the title De Tribus Impostoribus. It’s a wonder that Borges doesn’t mention this work, as he seems to have read absolutely everything, including all the books that don’t exist, and Browne is a particular favorite of his. In fact, the narrator of “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius” declares at the end:

… English and French and mere Spanish will disappear from the globe. The world will be Tlön. I pay no attention to all this and go on revising, in the still days at the Adrogué hotel, an uncertain Quevedian translation (which I do not intend to publish) of Browne’s Urn Burial.2

This “contamination of reality by dream,” as Borges calls it, is one of his pet themes, and commenting upon such contaminations is one of his favorite fictional devices. Like many of the best such devices, it turns the artist’s mode or form into a metaphor for his concerns, as does the diary ending of Portrait of the Artist As a Young Man or the cyclical construction of Finnegans Wake. In Borges’ case, the story “Tlön,” etc., for example, is a real piece of imagined reality in our world, analogous to those Tlönian artifacts called hrönir, which imagine themselves into existence. In short, it’s a paradigm of or metaphor for itself; not just the form of the story but the fact of the story is symbolic; “the medium is the message.”

Moreover, like all of Borges’ work, it illustrates in other of its aspects my subject: how an artist may paradoxically turn the felt ultimacies of our time into material and means for his work — paradoxically because by doing so he transcends what had appeared to be his refutation, in the same way that the mystic who transcends finitude is said to be enabled to live, spiritually and physically, in the finite world. Suppose you’re a writer by vocation — a “print-oriented bastard,” as the McLuhanites call us — and you feel, for example, that the novel, if not narrative literature generally, if not the printed word altogether, has by this hour of the world just about shot its bolt, as Leslie Fiedler and others maintain. (I’m inclined to agree, with reservations and hedges. Literary forms certainly have histories and historical contingencies, and it may well be that the novel’s time as a major art form is up, as the “times” of classical tragedy, grand opera, or the sonnet sequence came to be. No necessary cause for alarm in this at all, except perhaps to certain novelists, and one way to handle such a feeling might be to write a novel about it. Whether historically the novel expires or persists seems immaterial to me; if enough writers and critics feel apocalyptical about it, their feeling becomes a considerable cultural fact, like the feeling that Western civilization, or the world, is going to end rather soon. If you took a bunch of people out into the desert and the world didn’t end, you’d come home shamefaced, I imagine; but the persistence of an art form doesn’t invalidate work created in the comparable apocalyptic ambience. That’s one of the fringe benefits of being an artist instead of a prophet. There are others.) If you happened to be Vladimir Nabokov you might address that felt ultimacy by writing Pale Fire: a fine novel by a learned pedant, in the form of a pedantic commentary on a poem invented for the purpose. If you were Borges you might write Labyrinths: fictions by a learned librarian in the form of footnotes, as he describes them, to imaginary or hypothetical books.3 And I’ll add, since I believe Borges’ idea is rather more interesting, that if you were the author of this paper, you’d have written something like The Sot-Weed Factor or Giles Goat-Boy: novels which imitate the form of the Novel, by an author who imitates the role of Author.

IF THIS sort of thing sounds unpleasantly decadent, nevertheless it’s about where the genre began, with Quixote imitating Amadis of Gaul, Cervantes pretending to be the Cid Hamete Benengeli (and Alonso Quijano pretending to be Don Quixote), or Fielding parodying Richardson. “History repeats itself as farce” — meaning, of course, in the form or mode of farce, not that history is farcical. The imitation (like the Dadaist echoes in the work of the “intermedia” types) is something new and may be quite serious and passionate despite its farcical aspect. This is the important difference between a proper novel and a deliberate imitation of a novel, or a novel imitative of other sorts of documents. The first attempts (has been historically inclined to attempt) to imitate actions more or less directly, and its conventional devices — cause and effect, linear anecdote, characterization, authorial selection, arrangement, and interpretation — can be and have long since been objected to as obsolete notions, or metaphors for obsolete notions: Robbe-Grillet’s essays For a New Novel come to mind. There are replies to these objections, not to the point here, but one can see that in any case they’re obviated by imitations-of-novels, which attempt to represent not life directly but a representation of life. In fact such works are no more removed from “life” than Richardson’s or Goethe’s epistolary novels are: both imitate “real” documents, and the subject of both, ultimately, is life, not the documents. A novel is as much a piece of the real world as a letter, and the letters in The Sorrows of Young Werther are, after all, fictitious.

One might imaginably compound this imitation, and though Borges doesn’t, he’s fascinated with the idea: one of his frequenter literary allusions is to the 602nd night of The 1001 Nights, when, owing to a copyist’s error, Scheherezade begins to tell the King the story of the 1001 nights, from the beginning. Happily, the King interrupts; if he didn’t there’d be no 603rd night ever, and while this would solve Scheherezade’s problem — which is every storyteller’s problem: to publish or perish — it would put the “outside” author in a bind. (I suspect that Borges dreamed this whole thing up: the business he mentions isn’t in any edition of The 1001 Nights I’ve been able to consult. Not yet, anyhow: after reading “Tlön, Uqbar,” etc., one is inclined to recheck every semester or so.)

Now Borges (whom someone once vexedly accused me of inventing) is interested in the 602nd Night because it’s an instance of the story-within-the-story turned back upon itself, and his interest in such instances is threefold: first, as he himself declares, they disturb us metaphysically: when the characters in a work of fiction become readers or authors of the fiction they’re in, we’re reminded of the fictitious aspect of our own existence, one of Borges’ cardinal themes, as it was of Shakespeare, Calderón, Unamuno, and other folk. Second, the 602nd Night is a literary illustration of the regressus in infinitum, as are almost all of Borges’ principal images and motifs. Third, Scheherezade’s accidental gambit, like Borges’ other versions of the regressus in infinitum, is an image of the exhaustion, or attempted exhaustion, of possibilities — in this case literary possibilities — and so we return to our main subject.

What makes Borges’ stance, if you like, more interesting to me than, say, Nabokov’s or Beckett’s, is the premise with which he approaches literature; in the words of one of his editors: “For [Borges] no one has claim to originality in literature; all writers are more or less faithful amanuenses of the spirit, translators and annotators of pre-existing archetypes.” Thus his inclination to write brief comments on imaginary books: for one to attempt to add overtly to the sum of “original” literature by even so much as a conventional short story, not to mention a novel, would be too presumptuous, too naïve; literature has been done long since. A librarian’s point of view! And it would itself be too presumptuous if it weren’t part of a lively, passionately relevant metaphysical vision, and slyly employed against itself precisely to make new and original literature. Borges defines the Baroque as “that style which deliberately exhausts (or tries to exhaust) its possibilities and borders upon its own caricature.” While his own work is not Baroque, except intellectually (the Baroque was never so terse, laconic, economical), it suggests the view that intellectual and literary history has been Baroque, and has pretty well exhausted the possibilities of novelty. His ficciones are not only footnotes to imaginary texts, but postscripts to the real corpus of literature.

This premise gives resonance and relation to all his principal images. The facing mirrors that recur in his stories are a dual regressus. The doubles that his characters, like Nabokov’s, run afoul of suggest dizzying multiples and remind one of Browne’s remark that “every man is not only himself … men are lived over again.” (It would please Borges, and illustrate Browne’s point, to call Browne a precursor of Borges. “Every writer,” Borges says in his essay on Kafka, “creates his own precursors.”) Borges’ favorite third-century heretical sect is the Histriones — I think and hope he invented them — who believe that repetition is impossible in history and therefore live viciously in order to purge the future of the vices they commit: in other words, to exhaust the possibilities of the world in order to bring its end nearer.

The writer he most often mentions, after Cervantes, is Shakespeare; in one piece he imagines the playwright on his deathbed asking God to permit him to be one and himself, having been everyone and no one; God replies from the whirlwind that He is no one either; He has dreamed the world like Shakespeare, and including Shakespeare. Homer’s story in Book IV of the Odyssey, of Menelaus on the beach at Pharos, tackling Proteus, appeals profoundly to Borges: Proteus is he who “exhausts the guises of reality” while Menelaus — who, one recalls, disguised his own identity in order to ambush him — holds fast. Zeno’s paradox of Achilles and the Tortoise embodies a regressus in infinitum which Borges carries through philosophical history, pointing out that Aristotle uses it to refute Plato’s theory of forms, Hume to refute the possibility of cause and effect, Lewis Carroll to refute syllogistic deduction, William James to refute the notion of temporal passage, and Bradley to refute the general possibility of logical relations; Borges himself uses it, citing Schopenhauer, as evidence that the world is our dream, our idea, in which “tenuous and eternal crevices of unreason” can be found to remind us that our creation is false, or at least fictive.

The infinite library of one of his most popular stories is an image particularly pertinent to the literature of exhaustion; the “Library of Babel” houses every possible combination of alphabetical characters and spaces, and thus every possible book and statement, including your and my refutations and vindications, the history of the actual future, the history of every possible future, and, though he doesn’t mention it, the encyclopedias not only of Tlön but of every imaginable other world—since, as in Lucretius’ universe, the number of elements, and so of combinations, is finite (though very large), and the number of instances of each element and combination of elements is infinite, like the library itself.

That brings us to his favorite image of all, the labyrinth, and to my point. Labyrinths is the name of his most substantial translated volume, and the only full-length study of Borges in English, by Ana María Barrenechea, is called Borges the Labyrinth-Maker. A labyrinth, after all, is a place in which, ideally, all the possibilities of choice (of direction, in this case) are embodied, and — barring special dispensation like Theseus’ — must be exhausted before one reaches the heart. Where, mind, the Minotaur waits with two final possibilities: defeat and death, or victory and freedom. Now, in fact, the legendary Theseus is non-Baroque; thanks to Ariadne’s thread he can take a shortcut through the labyrinth at Knossos. But Menelaus on the beach at Pharos, for example, is genuinely Baroque in the Borgesian spirit, and illustrates a positive artistic morality in the literature of exhaustion. He is not there, after all, for kicks (any more than Borges and Beckett are in the fiction racket for their health): Menelaus is lost, in the larger labyrinth of the world, and has got to hold fast while the Old Man of the Sea exhausts reality’s frightening guises so that he may extort direction from him when Proteus returns to his “true” self. It’s a heroic enterprise, with salvation as its object — one recalls that the aim of the Histriones is to get history done with so that Jesus may come again the sooner, and that Shakespeare’s heroic metamorphoses culminate not merely in a theophany but in an apotheosis.

Now, not just any old body is equipped for this labor, and Theseus in the Cretan labyrinth becomes in the end the aptest image for Borges after all. Distressing as the fact is to us liberal Democrats, the commonality, alas, will always lose their way and their souls: it’s the chosen remnant, the virtuoso, the Thesean hero, who, confronted with Baroque reality, Baroque history, the Baroque state of his art, need not rehearse its possibilities to exhaustion, any more than Borges needs actually to write the Encyclopaedia of Tlön or the books in the Library of Babel. He need only be aware of their existence or possibility, acknowledge them, and with the aid of very special gifts — as extraordinary as saint- or hero-hood and not likely to be found in The New York Correspondence School of Literature — go straight through the maze to the accomplishment of his work.

- An ultimacy already attained in the nineteenth century by that avant-gardiste of East Aurora, New York, Elbert Hubbard, in his Essay on Silence. ↩

- Moreover, on rereading “Tlön,” etc., I find now a remark I’d swear wasn’t in it last year: that the eccentric American millionaire who endows the Encyclopaedia does so on condition that “the work will make no pact with the impostor Jesus Christ.” ↩

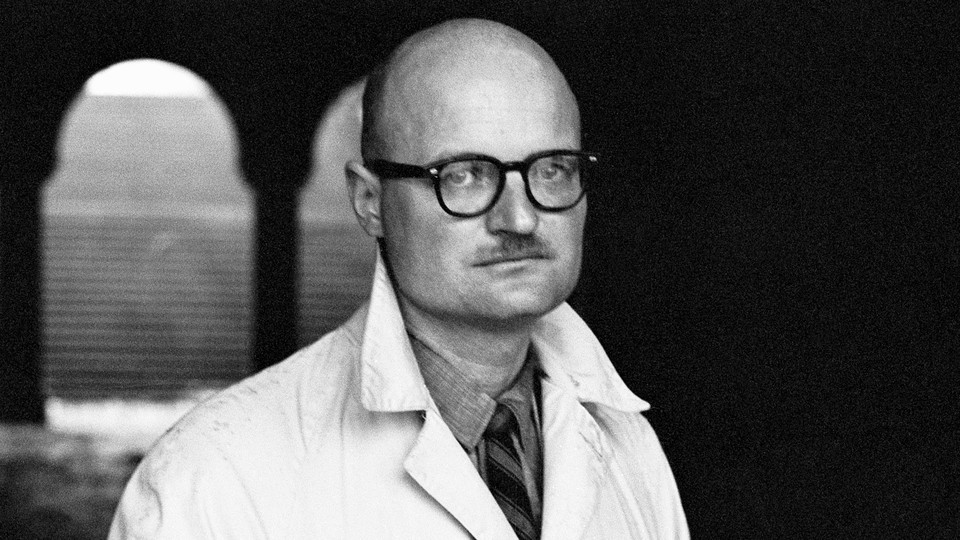

- Borges was born in Argentina in 1899, educated in Europe, and for some years worked as director of the National Library in Buenos Aires, except for a period when Juan Perón demoted him to the rank of provincial chicken inspector as a political humiliation. Currently he’s the Beowulf-man at the University of Buenos Aires. ↩