This week, women’s social club The Wing launches No Man’s Land, its first print magazine, with stories rolling out exclusively on the Cut.

We are sitting in the library of the Camp Etna Spiritualist Association, a 141-year old community for clairvoyants, mediums, psychics, and Spiritualists located in a small, rugged hamlet deep in the woods of central Maine. Diane Jackman, the camp’s historian, is in her mid-sixties — aqua blue eyes and flowing silver hair, dressed in a purple, moth-nibbled sweater — but she speaks with the vivacity of a teenager. Her late third husband, Fiddlin’ Red, was a former band member for Captain and Tennille. “Red and I had been making love for 30 minutes when he gasped then stiffened and all of a sudden I heard this big oomph!” Diane lifts her hands in the air to motion what happened next. “I felt his spirit fall through me. It felt like the spirit of the bird I had hit with my truck and killed just a few weeks before.” She screamed his name but Red was gone. Though, to hear Diane tell it, he wasn’t gone completely — she swears part of him still lingers inside of her.

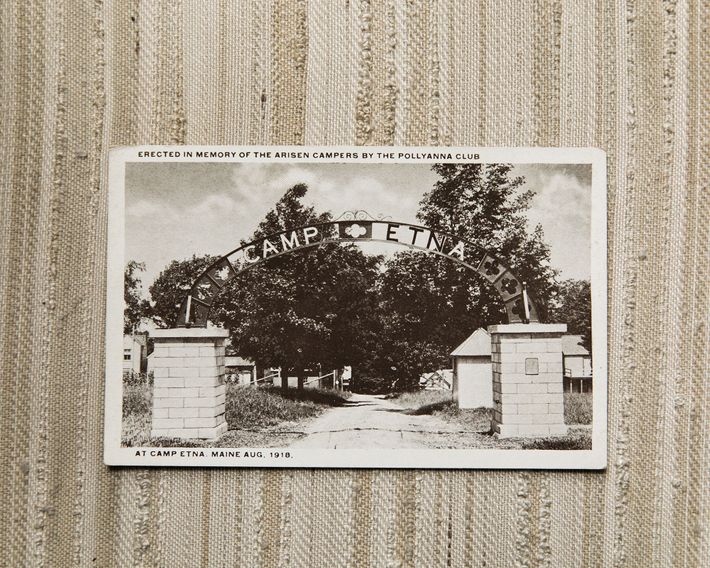

Diane began hitchhiking up the coast, working her way through Maine, content to spend her fifties as a volunteer carpenter. After Red passed, she felt his spirit guiding her on a pilgrimage. One day she saw an old, dilapidated church along the side of the road, covered in sunflowers, and just beyond she spied a purple wrought-iron entrance with white, bold letters: CAMP ETNA. She stepped through it, just as so many women had done before, and lifted the veil of her new life.

Etna, Maine (population 1,246) is a town better seen on a map than on the ground; stay on the highway and it is easily passed through like an apparition. It’s a town with a single clapboard post office, a goat farm, an apple orchard, a barn converted into the community gym, and properties with lawns and broken-down cars scattered in driveways. But turn left off the main drag of town, drive down a small gravel path, through the graceful iron gate announcing your arrival into the camp, and the road opens onto a grassy knoll surrounded by a bungalow community of one-room cottages. Many are painted purple, the camp’s preferred color, some are pink and purple, and nearly every one has a porch. Dream catchers, Buddha figures, and fairy statues decorate the windows of occupied bungalows, while the other structures slowly fade away or rot. Those still in business hang out their tin shingle to attract visitors: MEDIUM.

It was the Fox Sisters who introduced America to this new kind of public woman. On the night of March 31, 1848, 11-year-old Kate Fox made contact with the spirit world at a farmhouse in Hydesville, New York. The Fox family had been tormented by strange noises, bumps, and knocks, like someone was moving furniture around. That evening, according to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in his History of Spiritualism, Kate “challenged the unseen power to repeat the snaps of her fingers.” The knocking responded.

The rappings followed the sisters wherever they went, and within a year they began to perform séances in Rochester, New York City, and eventually across the country. Even if their spectators didn’t believe what the Fox sisters claimed to be true, it was likely the first time they had ever witnessed women — young, confident women at that — speak so passionately, so assuredly in public.

The same year, the Seneca Falls Convention, held over two days in July 1848, brought participants from all over to discuss the state of women in society.

The atmosphere was “alive with angels,” writes historian Ann Braude in her book Radical Spirits, which weaves together the parallel rise of Spiritualism and women’s rights in America. Many of the women who attended the convention praised the Fox sisters for their progressivism in resisting their roles as politically, financially, sexually, and socially repressed second-class citizens. Some even reported hearing raps on the small mahogany desk where Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucrecia Mott signed the Declaration of Sentiments. “Not all feminists were Spiritualists,” writes Braude, “but all Spiritualists advocated for women’s rights.”

Camp Etna planted its roots in 1858, when a local farmer began to hold Spiritualist meetings in a grove on the banks of a large, shallow pond. Today there are 15 women living full-time at the camp. Arlene Grant, one of the year-round residents, moved here in the 1960s, a time when Spiritualism the religion came into conflict with Spiritualism, the concept: the practice of free will and free love. For women to communicate a will to power, death no longer need to be breached. But to the women who had spent so long speaking to the dead, it was an affront to their very existence.

“Back then, you had to jump through hoops to prove that you were the real deal as a Spiritualist,” Arlene told me. “You couldn’t just say you were a medium — you had to prove it.”

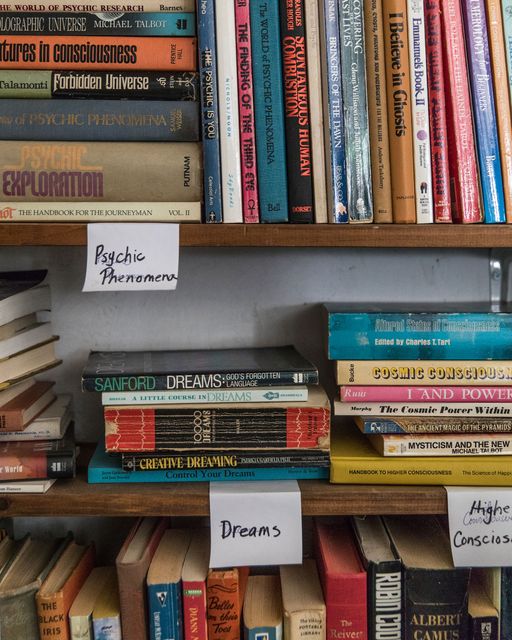

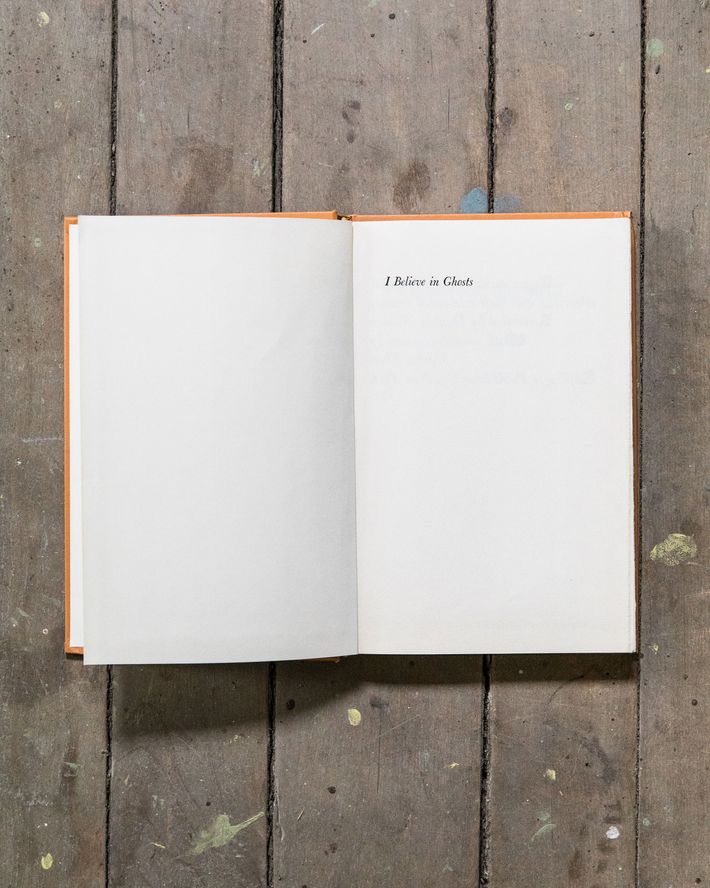

To the hippies, Spiritualism fit in nicely to the appealing new movements they were experimenting with: self-guidance, communal living, meditation, mysticism, a life of pleasure and less paint, a close relationship with the environment, living by the golden rule. I ask Arlene about the ebbs and flows of the camp. She is angry, and not afraid to show it, about the “new agey” stuff coming into Camp Etna since the 1960s. “Now we have all this ghost hunting, paranormal crap. Tarot cards and angel painting and all that crap when used to be just straight-up Spiritualism. And mediums proved they were real. Now, anyone can come here. It’s bullshit,” she says, sitting in a dark cabin at the edge of camp.

Diane tells me otherwise. That all are welcome; their population is on the rise. I’d been beginning to worry about the fate of Spiritualism and Camp Etna, sentimental that its purpose was expired. But looking around, not only at the women at the camp but at the women in my life, I realized that Spiritualism had done what it had meant to do — it gave women power. It gave women an opportunity and safe place to use their voices, and made it acceptable for women to speak from their gut, from their intuition and instinct, from their minds as well as their hearts. The feminist spirit of Spiritualism wasn’t dead; it was a ghost living among us. It hadn’t shriveled up. It lingered on.

Mira Ptacin is writing a book about Camp Etna entitled The In-Betweens, which is forthcoming by Liveright Publishing.