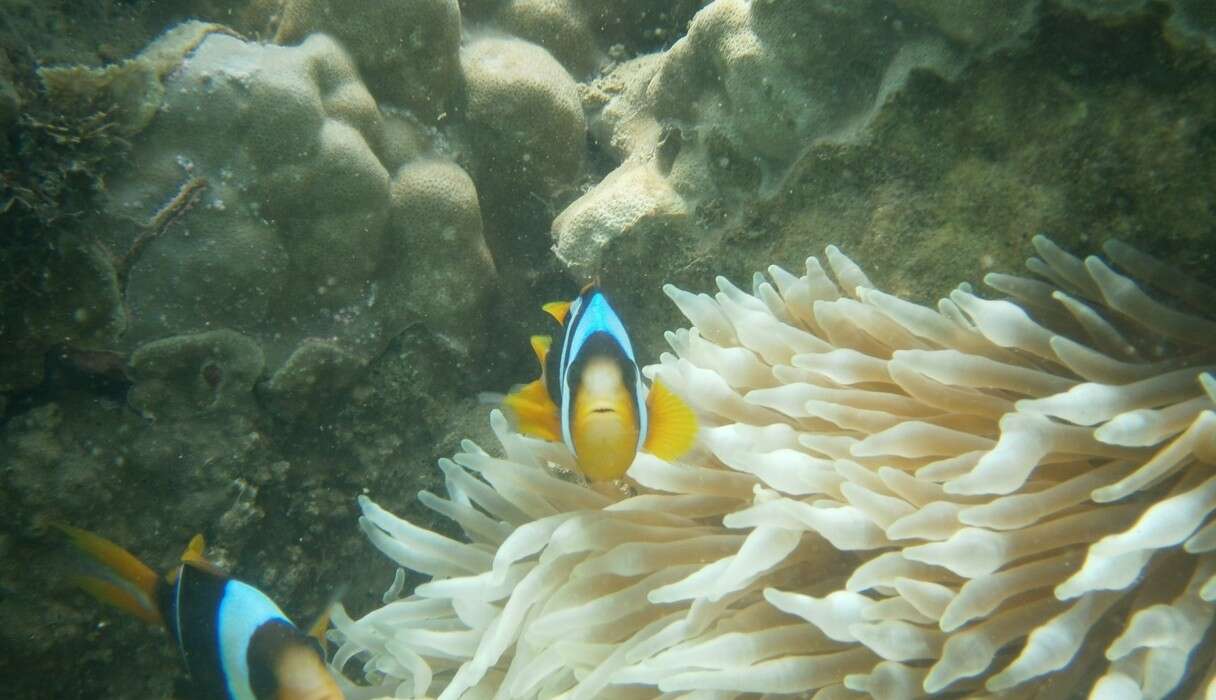

Tiny Fish Has A Poisonous Protector From Ocean Threats

Anemone fish, made famous by the animated blockbuster "Finding Nemo" are some of the most interesting species one will find on a coral reef. Commonly referred to as clownfish, these little critters, belonging to the damselfish family (Pomacentridae) are never to be found without an anemone. While this might not sound that ground-breaking, given that many species throughout the animal kingdom are only ever found living in one specific environment, it becomes much more noteworthy when you discover that anemones are poisonous and are capable of injecting some rather toxic venom.

Anemones belong to the phylum Cnidaria, whose distinguishing feature is the adaptation of nematocysts. These are little cells located on tentacles which consist of a trigger-hair known as a cnidocil, a pointed barb attached to a coiled string and a sac of venom. When tissue from another organism triggers the cell, the barb proceeds to penetrate and inject the venom. Tentacles on anemones are covered in these cells, yet the humble clownfish has developed means to avoid this toxic hazard. There are over a 1,000 species of anemone (incidentally clownfish happen to inhabit only 10 of these) and they live in tropical environments relying on the sunlight in the same way that hard and soft corals do.

For a while marine ecologists were stumped as to how the anemone fish avoided the danger posed by the anemones. There were several theories: first off, that the tentacles of the 10 host anemone species have somehow evolved not contain nematocysts; secondly that the clownfish do not actually touch the anemones' tentacles; that the skin of clownfish is thicker than that of other damsels and other reef fish; or finally that the anemones choose not to fire when the clownfish is present. All of these were found to be wrong - the 10 host anemones all contain nematocysts; the clownfish do indeed touch the tentacles (although it is true that other species such as the three-spot dascylus will hide behind anemones for protection without venturing within the tentacles); the skin of clownfish is in no way noticeably thicker than any other fish species of the same size; and while anemones appear to have the ability to control whether their nematocysts fire or not it has been observed that they can sting and consume in a predatory manner while a clownfish is simultaneously nestled within their tentacles.

Yet the anemone fish get protection somehow. In laboratory experiments clownfish that were separated from their host anemones for merely a few days appeared to swim away from the anemone rapidly in a manner befitting a painful sting after they had been reunited. A stung anemone fish would then be seen to return to the anemone tentatively, perhaps to gradually expose itself to the stings of the host; ventral fins first, then after a while, the whole belly. Most scientist currently believe that the mucus secreted by the clownfish serves to prevent the nematocysts firing - either by disguising it from the stinging cells, a sort of chemical camouflage - or indeed by acting as a barrier for the fish, preventing the venom from entering. This mucus has to be constantly secreted by the fish so that it remains protected. In the famous aforementioned movie there is a seen where Nemo's father tells him to rub the anemone in the morning to remain immune to the sting - it would seem this is surprisingly accurate.

Clearly the poison of the anemones serves to protect the clownfish from its predators, a very useful ecological advantage for an otherwise rather defenseless fish. This is an example of symbiosis - interactions between two species that live along side each other. Rather than being mutualistic (where both parties benefit) this is an example of a commensal relationship; the clownfish provide very little positive feedback to their hosts. While it is true that some individuals will bring food to the anemones, this is nowhere near substantial. Anemones themselves are capable of stinging and capturing prey with their tentacles, provided it is small enough to fit in their mouths. On top of this they also often play host to photosynthetic algae that provide them with glucose (this is another example of symbiosis). Perhaps this is why clownfish are so protective of their homes, scaring away the majority of fish that swim by, occasionally braving an aggressive swim at a passing diver.

One of the most interesting aspects of clownfish biology is how they reproduce. They are sequential hermaphrodites - meaning they are all born as one gender and then once they are mature enough they will change into the other gender. This phenomenon is seen in many reef fish species, with several wrasse (Labridae), parrotfish (Scaridae) and anthias (Anthiinae) all opting for the same reproductive strategy. Some of these will start as females and develop into males (protogynous hermphrodites), others are vice versa; starting as males and turning into females (protandrous hermaphrodites). Clownfish are examples of the latter. Interestingly enough, it is stress that keeps them male, so the dominant female in the anemone will bully all the others males so that they stay male. She then has the monopoly on sexual reproduction. Once the dominant female dies the next biggest male subordinate will exhibit hormonal changes that facilitate the sequential hermaphroditism. To use "Finding Nemo" as an analogy again; when Nemo's mother dies at the beginning, Nemo's father would then change sex and become a female. Nemo, being the next biggest male in the anemone would become the sexual partner of the dominant female, until it was his turn to change gender. So despite eventually being found that would make a pretty traumatic homecoming for poor little Nemo. It stands to reason that if their film was more biologically accurate then Disney-Pixar may have to upgrade the age-rating to at least a 15.

PS - sorry for the spoilers.

By Madagascar ARO, Rob Macfarlane Learn more about Frontier's marine conservation and diving projects that run across the world.

Join the Frontier Community online with Facebook, Twitter, and Pinterest.