Justice Rosalie Abella on the front steps of the Supreme Court in Ottawa, where she has served for 17 years.Dave Chan/The Globe and Mail

For those who knew the story of Supreme Court Justice Rosalie Abella, it was hard not to notice how it echoed, at least in a small way, that of the 16-year-old Tamil boy. Police in Sri Lanka had beaten and detained Jeyakannan Kanthasamy, and he’d fled to Canada with an uncle. But when his refugee claim was denied, he asked to stay on “humanitarian and compassionate” grounds. And Canada told him no.

First it was a federal officer, saying he had not proved “undeserved hardship.” He had failed to show his post-traumatic stress couldn’t be treated back home; even his diagnosis didn’t mean much, the officer said, since the psychologist who made it hadn’t witnessed the beating. Two levels of court – four judges in all – affirmed the rejection.

Then the case came before the Supreme Court, and Justice Abella did not hold back. The concept of undeserved hardship for children should not have been applied, she wrote, since children rarely, if ever, deserve hardship. Even if he’d been an adult, the law required genuine compassion, not an “anemic,” “constricted” ticking of legal boxes. (She flatly rejected any requirement to prove a lack of treatment back home or for a psychologist to have direct knowledge of events.)

Her 5-2 ruling in 2015 would define compassion – in the legal and literal sense – in federal immigration law. And Mr. Kanthasamy would ultimately remain in Canada.

Canada’s Supreme Court already requires diversity. Why not racial diversity, too?

On July 1, Justice Abella turns 75, the midnight hour for Supreme Court judges. In her body of roughly 200 rulings spanning 17 years on Canada’s highest court and covering nearly every major area of law, she has fought for the underdog and the vulnerable, and helped set the court’s moral tone.

And she has done so not from the court’s margins, but largely as a voice for the majority.

Her impact, says Eric Gertner, a co-founder of the Supreme Court Law Review, has been to make the law more humane. It’s an unusually personal legacy for a jurist. A child of Holocaust survivors, Justice Abella helped extend the reach of Canadian courts globally in human-rights cases and pushed for substantive equality based on the lived experiences of women and minorities. In her spare time, she gave speeches around the world fusing her personal story with a lesson on why judges must stand up to the tyranny of the majority.

Her influence has been felt internationally.

“Rosie Abella’s work in human rights and constitutional law on the Supreme Court … is drawn on by judges in all the senior courts of the Common Law world,” says Sian Elias, a former chief justice of New Zealand.

And the events that shaped the judge ultimately shaped the law.

Justice Abella's parents, Fanny Krongold and Jacob Silberman, with their two-year-old son, Julius. He was murdered at the Treblinka death camp, along with Jacob's mother and three brothers.Dave Chan/Courtesy of Family

History’s most powerful and terrible currents delivered Rosalie Silberman to Canada’s shores.

Her parents, Fanny Krongold and Jacob Silberman, got married in Poland on Sept. 3, 1939, two days after the Nazi invasion. Fanny was a businesswoman and daughter of a wealthy factory owner. Jacob was an intellectual, the poor son of a bookshop owner. He’d just finished eight years of legal training, but under Nazi rule, Jews couldn’t practise law.

By October, 1942, the couple had a two-year-old son, Julius. That month, the family was rounded up. A German shot Jacob’s father, Zysman. Julius – along with Jacob’s mother, Rosalia, and his three younger brothers, Viktorek , Menush and Shimon – were sent to Treblinka, a death camp near Warsaw. They were all murdered.

Jacob was ultimately deported to Buchenwald, a forced-labour camp in Germany; Fanny and her mother, Zysla, landed in another part of the same camp.

After the war, Fanny learned her husband was in Theresienstadt, in Czechoslavakia, and she rode the rails to fetch him, only to find the camp barred to visitors because of a typhoid outbreak. She sneaked in, using a garbage detail for cover, and smuggled him out. They returned to Poland, but the family factory, which was taken over by the Germans after the invasion, had since been nationalized by the Poles. It wasn’t safe; there were pogroms. They went to Berlin and on to Stuttgart, where the family (including Zysla) lived in a community of displaced persons.

They began rebuilding their lives. Jacob taught himself English, and the Americans who were in charge hired him to help set up legal services for other DPs in southwest Germany. They had Rosalie in 1946, on Canada’s birthday; her sister, Toni, followed two years later.

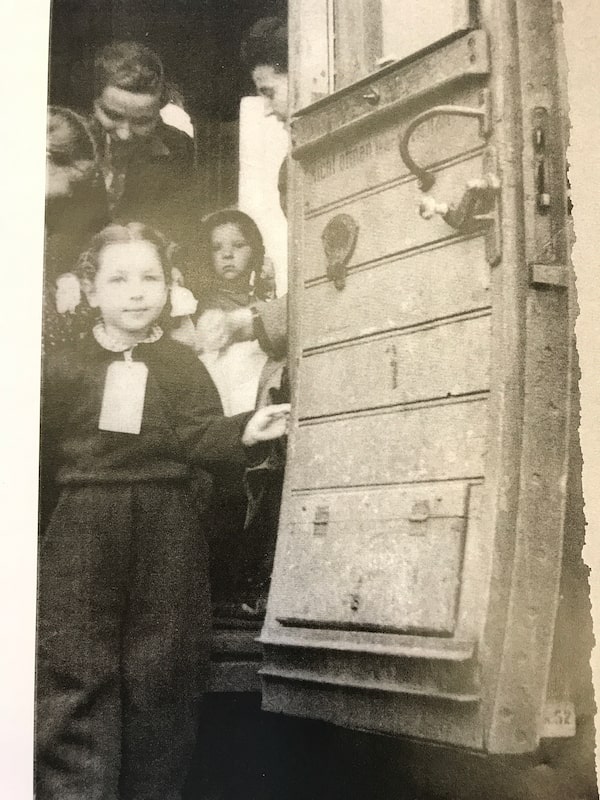

Rosalie Silberman and her younger sister, Toni, on the train to Bremerhaven, where they would board a ship bound for Halifax in May 1950.Courtesy of Family

The Silbermans arrived in Canada in 1950. To slip between cracks in the wall the country had built against Jews, the family faced bureaucratic reasoning not unlike that confronted by young Mr. Kanthasamy six decades later. Rosalie’s lawyer father had to be classified as a “tailor’s cutter” to gain entry. (The story of DPs having to become tailors to get into Canada would later be told in a book co-authored by Justice Abella’s husband, Irving Abella, called None is Too Many: Canada and the Jews of Europe 1933-1948.)

Because her father wasn’t yet a citizen, he couldn’t practise law, and the family couldn’t afford to wait five years. So he became, without lament, an insurance agent. But Rosalie vowed – at age 4 – to become, in his stead, a lawyer.

“The whole story of my parents and family is always a story I’ve had trouble processing,” says Justice Abella during a three-hour interview days after her final hearing in May. “I just can’t see myself being as courageous as they were and then coming out the other end with a determination and resilience to go on without grieving.”

All these events – the loss of the brother she never knew; the search for home in a world in which discrimination and exclusion persisted; the use of law to disenfranchise; even her parents’ insistence on looking forward – would shape the future judge.

And so, too, would a happy, even idyllic, childhood. “Now I look back and see that my whole life was constructed in an environment that was an exuberant rebuke to history,” she said in 1992, when she was sworn in to the Ontario Court of Appeal.

Her legal career would provide its own exuberant rebukes.

Justice Abella and her Supreme Court colleagues arrive in the Senate chamber ahead of the Speech from the Throne in March 2010.Reuters

Canada does not have a simple demarcation line between liberal and conservative judges. In the United States, there are two main camps: those who believe the Constitution is a “living tree,” changing with the times (the liberals); and the originalists, who support an interpretation of constitutional rights rooted in a quasi-religious view of the documents created by the Founding Fathers (the conservatives).

In Canada, the living-tree version of the law is almost universally accepted at all levels of court. The line between liberals and conservatives tends to revolve around “the separation of powers” – that is, are judges staying in their lane, or are they usurping the politicians’ job of making laws? Are they cautious incrementalists or bold change-makers? It’s a blurry line, since all judges accept their obligation under the Charter to review the content of laws.

There’s little doubt about where Justice Abella stands.

Consider Google v. Equustek in 2017, the first case of its kind globally. A small tech company in B.C. was seeking a worldwide order that would force Google to drop the websites of a rival company it had accused of stealing its trade secrets.

With Justice Abella writing for a 7-2 majority, the Supreme Court ruled that in the internet age, Canada’s courts must have global reach to enforce their injunctions. That includes making orders against third parties such as Google that weren’t involved in the original dispute.

“Not being afraid to be the first as a court is, I think, part of what’s made other courts look to us, whether they follow us or not,” Justice Abella says. “And often they do, in the rights area. It’s been its willingness to go out on a limb and set up new legal propositions that suit the times, as we were admonished to do in 1929 by Lord Sankey, who said, ‘This is a living tree. Water it.’ ”

Here she’s referring to the famous case in which women in Canada were ruled to be “persons” under the law. John Sankey, a British judge (at the time, Supreme Court rulings could be appealed to Britain) spoke of the 1867 Canadian Constitution as being capable of growth and expansion within its natural limits.

Justice Abella put two words in his mouth: “water it” – crystallizing her liberal viewpoint of the judge’s role in a constitutional democracy.

That notion is part of her legacy. In the second generation of the 1982 Charter of Rights and Freedoms, she has watered the tree, and it has continued to grow.

Justice Abella was appointed to the Family Court In 1976, at age 29. She says that seven-year period was the only time she lost sleep over her decisions.The Globe and Mail

To see Justice Abella presiding over a Supreme Court webcast hearing – in a mask glittering with sequins – is to know she is comfortable in her unconventionality. She’s no formalist.

Formalism means applying law to the facts of a case without regard for social or policy concerns. But she isn’t content with philosophies that focus on a statute’s literal meaning or on precedent, while “tending to deny the moral component of decision-making,” as she put it in a 1989 article in the McGill Law Journal.

“The law is there for the public, to serve the public, and to serve the public’s need for justice,” she says now. “And it’s true those are all malleable terms and that everybody’s view of what that means is different. But I believe there is nonetheless a way to approach law that makes it more accessible in substantive and procedural terms. And I’m for the more accessible.”

She had an epiphany in the mid-1990s, while reading Hitler’s Justice: The Courts of the Third Reich, by German author Ingo Muller. German judges and law professors had developed a legal foundation for Nazi policies of dehumanization and murder. But they would say they were just following the “rule of law.”

“I realized what an empty phrase it was,” says Justice Abella. “Because it was also the rule of law that brought us segregation and apartheid. Much of what’s done in the name of the rule of law can be unjust.” A judge’s role, she believes, should be to support a “just rule of law” or a “rule of justice,” a notion that evokes a more assertive purpose.

The sequined mask is a clue to her judicial approach. It is mischievous, boundary-pushing. Like her aversion to the ubiquitous “rule of law,” it sets her apart.

Consider Justice Abella’s north Toronto home and her Supreme Court chambers, says Albie Sachs, a retired judge from South Africa’s Constitutional Court: Both are filled with art and kitsch and cartoon characters.

“For me, that’s part and parcel of our project,” says Mr. Sachs, who met Justice Abella at a conference in the late 1990s and has since visited both her home and office. “It’s the imagination at work. The way that feeling and texture come into reasoning ... it’s the opposite of formalism.”

Mr. Sachs, too, was shaped by extraordinary world events. He had his right arm blown off and was blinded in one eye when South Africa’s security police planted a bomb in his car during apartheid. So he’s well-placed to offer insight into Justice Abella. In his view, she challenges the solemn demeanour, the rigidity, the formality and formalism, of many judges.

“We serve the law best when we do so spontaneously, in our own way, with our own voice, and don’t try to force ourselves to comply with some artificial, ideal-type notion of how a judge should be,” he says. “In essence, what our inner selves are seeking is to humanize the law, reduce its artificiality.”

Judge Rosalie Abella, head of the Royal Commission into Equality in Employment, holds the report she and the commission released in Ottawa, Nov. 20, 1984.

Back in 1979, when Justice Abella was a young judge on the Ontario Family Court, one law in need of humanizing denied unemployment benefits to pregnant women. The Supreme Court unanimously upheld the denial, saying: “Any inequality between the sexes in this area is not created by legislation but by nature.”

Justice Abella, meanwhile, was a working mother, raising two boys in an atmosphere of equality with her husband (they’ve been married more than 50 years). “We were equal at home: Neither of us cooked or cleaned,” she told an audience at the University of Toronto two years ago. “He was there every day when they came home after school. The kids say they have two mothers – one has a beard.” (There is a bit of a stand-up comic in Justice Abella.)

The young judge would soon help ensure “nature” could no longer affect a woman’s right to equality. In 1983, Liberal cabinet minister Lloyd Axworthy asked her to lead a one-woman royal commission on equality in employment. In a six-week period, she held 92 meetings in 17 cities with women, visible minorities, Indigenous peoples and disabled persons.

Her 1984 report on “employment equity” – a neutral term she coined to replace the emotionally loaded “affirmative action” – broke new ground. Discrimination, she wrote, did not require the intent to obstruct someone’s opportunities; the effect mattered, too. Her focus was on “substantive equality,” which meant taking a deep look at an individual’s or group’s lived experience.

Her work led to federal employment-equity legislation in 1986 – adopted by the Progressive Conservative government of Brian Mulroney and still in existence – and inspired similar fair-employment laws in Northern Ireland, New Zealand and South Africa.

“She put substantive equality on the map,” Mr. Sachs says. “I think she found the right register. It wasn’t done in a tone of harangue or with a sense of victimhood. It was done affirmatively and confidently. She was finding the language for quite a profound movement in Canada and the world.”

Substantive equality would become the foundation of the Supreme Court’s first equality ruling under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, in 1989. By chance, that ruling involved the same issue Justice Abella’s father had faced: a non-citizen who wished to practise law. The non-citizen won, and the court cited her definition of discrimination from her 1984 report.

Still, what substantive equality requires in a particular case is, even three decades later, still in dispute.

Consider Fraser v. Canada (2020), involving an RCMP job-sharing program mostly used by women with children. The job-sharers weren’t allowed to make full contributions to their pensions, yet others away on leave, or even under suspension, could. Three mothers who enrolled in the program filed an internal grievance.

They lost. Eventually the case reached the courts. Both the Federal Court and Federal Court of Appeal rejected the women’s claim of discrimination under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. At the Supreme Court, two judges argued it had been the women’s choice to join the job-sharing program. The Mounties, they said, had created it to help women and should not be punished for having done so. A third judge said that while the pension rules might have been illogical, it was up it to legislators, not judges, to correct.

In 1984, under the Progressive Conservative government of Brian Mulroney, Judge Abella delivered a report on 'employment equity' – a term she coined to replace 'affirmative action' – that led to federal legislation two years later. That legislation still exists and inspired similar fair-employment laws in Northern Ireland, New Zealand and South Africa.Tibor Kolley/The Globe and Mail

Justice Abella – the mother of employment equity – would have her say. A woman’s ability to choose is often illusory when they bear the majority of household responsibilities, she wrote for a 6-3 majority. One of the three women had described being a full-time Mountie and mother as “hell on earth.” The RCMP had perpetuated the disadvantages they faced as women, and that was discriminatory, she added. (She even hinted that “choice” wasn’t all that different from “nature.”)

Debate was, by Canadian standards, harsh. Justice Malcolm Rowe and Justice Russell Brown called her majority opinion “truly arbitrary,” a product of “personal preferences,” and “antithetical to any notion of judicial restraint.”

“The result of all this is corrosive of the rule of law,” they wrote in a joint dissent, wielding the phrase she dislikes.

Justice Abella did not turn the other cheek: “Setting straw men on fire is not what we mean by illumination,” she replied in her ruling, quoting from a New Yorker article written by her friend, the journalist Adam Gopnik.

It was an exuberant rebuke – to the history of how women have been treated in the workplace and at home, and to her critics on the court.

Rosalie Abella as a baby in the Stuttgart camp for displaced persons: Holding her is Zysla Krongold, her maternal grandmother, with the two flanked by her parents, Jack and Fanny Silberman, whose first-born, two-year-old son Julius, had been among the family members lost to the Holocaust.

In childhood, Justice Abella turned to fiction to understand life. Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables, in particular, would link her sense that her father had been wronged to the career that lay ahead.

“It was the book that taught me what injustice looked like,” she says now. “A man who served 19 years for stealing a loaf of bread.”

Her parents had somehow managed to create an environment at once protective and open to the world around them. In Stuttgart, German was her mother tongue. It would be years before she understood how unusual that was for Holocaust survivors from Poland, and she asked her parents why they had raised them so. “They wanted us to feel we belonged,” she says.

Her parents were determined to get on with life. But she wanted to know everything, and her parents had little of the reticence so often documented among survivors.

“I was so curious, because my family was so different from every other kid’s family. So I kept asking questions,” she says. “ ‘What was it like in the camps? How did you feel when you found out your son wasn’t there? Did you miss Daddy? Was the work hard? What were the people like?’ There was never a tear. Never anger, never bitterness, and never hesitation in disclosing anything.”

She grew up in a middle-class, predominantly Gentile neighbourhood near Oakwood and St. Clair avenues in Toronto.

It was not all light. Her parents told her Julius had been a remarkable child, brilliant, even charismatic, and fluent in two languages, Polish and Yiddish.

“I wanted not to disappoint,” Justice Abella says.

By 12, she had read the entire children’s library at the Dufferin Street branch. The adult library was across the hall – “it was a Rubicon” – and barred children under 14. But it made an exception for her. She quickly found her way to Hugo.

Novels, she says, taught her what life was like outside her happy family. She would go on to read, in translation, the Russians (including all of Dostoyevsky), French writers such as Flaubert and Balzac and, over two summers in her 30s, Proust. Eventually she would discover the Americans – Bellow, Malamud, Cheever, Updike, later Roth (she didn’t like his early work) – and the British. She would even, one summer, purchase the 80 or so Modern Library titles she had missed out on from a top-100 list of novels and read them. She was also a member of the jury for the 2003 Giller Prize.

“In the introduction to Ralph Ellison’s book Invisible Man, he talks about novels being about the ‘human universals.’ And I never forgot the phrase, because in a good book is where you learn about the human universals,” she says. “It’s actually one of the reasons I naturally gravitate to comparative law. All legal problems are universal.”

Exuberance at times gave way to despair.

Handout

In her second year of law at the University of Toronto, as she was starting exams, her father, just 59, was diagnosed with liver cancer. She was jolted; her marks suffered. When she had difficulty finding an articling position, she considered quitting.

Two professors stand out in her memory for the help they offered at a vulnerable time: Ralph Scane, who said her father needed to know she would carry on, and Richard Risk, whose father, John Risk, gave her the articling job at his small downtown law firm.

Mere weeks before she graduated, her father died. Rosalie Silberman didn’t go to her graduation.

Her launch as a lawyer made her question the law’s purpose. She was practising nearly every kind of law – criminal, civil, corporate, real estate, wills, contracts, family. (She did two years at a two-person firm and two on her own.)

“I saw the world differently once I had clients, because I saw what the world looked like to them,” she says. “I saw how disconnected the law was from their reality.”

Practising law, she says, “is an exercise in figuring out how to give law legs, how to make it work for people. The interstices between the rules, the human dimensions. I came to see every client as a separate novel.”

In 1976, when she was seven months pregnant and not yet 30, Ontario Progressive Conservative Attorney-General Roy McMurtry appointed her to the Family Court, on which she sat for seven years, hearing child welfare, juvenile delinquency and spousal support cases.

She signalled early on that she was not content with the paternalistic status quo. A career favourite decision came in 1979, when she set out the appropriate role for government-appointed legal advocates in child-welfare cases: that is, to take instructions from the child, as much as possible, rather than to express their view of the child’s best interests.

It was the only period of her career when she lost sleep over her decisions as a judge, she says.

Then came an eight-year period where she acquired intense real-world knowledge and academic heft, first as chair of the Ontario Labour Relations Board (withdrawing as a judge when Attorney-General Ian Scott decided it was inappropriate for a judge to sit on a board or tribunal), later as chair of the Ontario Law Reform Commission, and also as a part-time professor at McGill from 1988 to 1992. She was involved in the country’s political life, too, serving as moderator of the federal leaders’ English-language debate, featuring Brian Mulroney, John Turner and Ed Broadbent.

Her mother later rebuked her for her nerviness: “You interrupted the prime minister!” And she wouldn’t be the last to criticize Justice Abella for that quality.

Supreme Court of Canada Justice Rosalie Abella, third from left, lights the menorah with Cantor Rabbi Daniel Benlolo, left, and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau during Hanukkah on the Hill celebrations on Parliament Hill in Ottawa on Dec. 5, 2018.Justin Tang/The Canadian Press

Hersch Lauterpacht and Raphael Lemkin were European Jewish lawyers, roughly contemporaries of Justice Abella’s father, and their story had a deep impact on her views of international law.

Mr. Lauterpacht created the concept of “crimes against humanity” so that a country’s leaders could be held responsible for what they did to their own people. While he was drafting an International Bill of Rights of Man in England, his close relatives were in hiding beneath a parquet floor in a house in Eastern Europe. Mr. Lemkin coined the term “genocide.” Their story is told in one of Justice Abella’s favourite books, East West Street, by international lawyer Philippe Sands of London.

In their day – before the end of the Second World War – international law served the state. “In short, the state could do whatever it wanted to its nationals. It could discriminate, torture or kill,” Mr. Sands wrote in his 2016 book.

“I was struck by the tenacity they had in getting their views implemented,” Justice Abella says. “Who were they to insist to the world and to get acceptance of these novel concepts that would completely redefine human rights?”

She would eventually have her own chance to do so.

The case was Nevsun Resources Ltd. v. Gize Araya (2020). It posed a novel question: Could workers sue a Canadian company in Canada for alleged crimes against humanity in Eritrea, where the reach of Canadian courts had never been held to exist?

Mr. Araya’s unproven allegation was that Nevsun had conspired with Eritrea’s military to force him and others to work indefinitely in a mine for subsistence wages. If they tried to flee, they were subjected to “the helicopter” – their elbows were bound together behind their back and their feet tied at the ankles, and they were left in the 50-degree sun for an hour.

Justice Abella’s response, on behalf of a 5-4 majority: Individual rights now transcend state boundaries. Human-rights law was “the phoenix that rose from the ashes of the Second World War,” and its basic norms “were not meant to be theoretical aspirations or legal luxuries, but moral imperatives and legal necessities.” Those norms are automatically a part of Canadian common law, she wrote. Nevsun could be sued in Canada. (The company, by that time acquired by a Chinese outfit, reached a confidential settlement with Mr. Araya and the other workers six months later.)

“The individual human being ... is the ultimate unit of all law,” she wrote, quoting Mr. Lauterpacht and footnoting East West Street.

It was another rebuke of history. Harold Hongju Koh, an international law professor and former dean at Yale, calls it “pathbreaking,” and adds that the United States Supreme Court has been asked the same question more than once and has declined to answer.

The ruling’s legacy: Canadian mining (and other) companies are liable in Canada for human-rights abuses abroad, putting an onus on the companies to ensure respect for individual rights.

On May 21, Justice Abella donned her trademark sequin mask to bid farewell to her colleagues on her last day in the Supreme Court.Jonathan Trottier/Supreme Court of Canada

Justice Abella has always had her critics. Too left-wing, they said. Too activist.

Brian Mulroney heard the criticism when he was prime minister in 1992. There was a vacancy on the Ontario Court of Appeal, a launching pad for future Supreme Court judges.

“The knock against her, when we were looking at where we were going to go, was that Rosie was an extremist,” says Mr. Mulroney today. “I said, ‘That’s nuts. She is a moderate, reasonable, thoughtful, highly intelligent Canadian. And she’s going to do a job that will be consistent with the growth and evolution of Canada.’ ”

His government appointed her to the appeal court, setting the stage for Liberal prime minister Paul Martin to name her to the Supreme Court in 2004, acting on a recommendation from justice minister Irwin Cotler. “What stood out was her compassion for the vulnerable and for the rights of the vulnerable,” Mr. Martin says.

And it stands out today, after 17 years on the Supreme Court.

There are two main threads in her rulings, according to University of Alberta law professor Malcolm Lavoie, who clerked for her from 2013 to 2014.

“The first is a commitment to the protection of vulnerable parties, including workers in a labour and employment context, the accused in criminal proceedings, Indigenous peoples in Aboriginal-rights cases, and traditionally disadvantaged groups in equality and discrimination cases,” he says. “The second thread is a belief in the capacity of the state as a force for good.”

Sometimes the two principles are in tension. Consider Saskatchewan Federation of Labour v. Saskatchewan, in 2015. Saskatchewan had limited the right to strike for public-sector workers it deemed essential. The Supreme Court had said in 1987 that the Charter of Rights and Freedom did not protect the right to strike. But with Justice Abella writing for a 5-2 majority, the court departed from precedent and declared the right to strike protected by the Charter.

In her ruling, she argued the withdrawal of labour is essential to a fair and meaningful process of collective bargaining. “Clearly the arc bends increasingly towards workplace justice,” she wrote.

Toronto lawyer Andrew Bernstein, a close observer of the Supreme Court, says it’s probably her most controversial ruling, partly because “when you ask what’s changed since 1987, the answer is ‘Not that much.’ Justice Abella, and enough of her colleagues, simply believed that the original decision was wrong, and she reversed it.”

Another quintessential ruling on constitutional rights was in R v. D.B. in 2008. A 17-year-old pleaded guilty to manslaughter after his punch killed an 18-year-old. Federal sentencing law made manslaughter a “presumptive” offence for an adult penalty; the onus was on the youth, not the Crown, to show why he deserved a youth penalty and a publication ban on his identity.

Justice Abella wrote for a 5-4 majority that the presumption of an adult penalty for youth could not stand (though they can still receive adult penalties if the Crown can show the need for them). And the diminished moral blameworthiness of youth for crime is a fundamental principle of justice, she wrote.

Not that she’s always in the majority. In Mikisew, an Indigenous-rights case in 2018, she wrote for herself and just one other judge that when governments make laws that affect treaty rights, they should first have to consult with Indigenous groups.

Religious freedom is also deeply important to her. In R v. N.S. in 2012, she was the only one to say that a Muslim complainant in a sexual-assault case should not have to choose between wearing her niqab and participating in the justice system. Similarly, in Alberta v. Hutterian Brethren in 2009, she said in dissent that Hutterites who refused to be photographed for their drivers’ licences should be accommodated.

In several other religious-freedom cases, she wrote for the majority. Bruker v. Marcovitz in 2014 involved a Jewish husband denying his wife a “get” – a religious divorce – even though he had contracted before his marriage not to withhold one in the event of a split. Justice Abella wrote for a 7-2 majority that the wife had a right to sue in a Canadian secular court, because religious freedom stops when Canadian values of equality are infringed.

“In my view, Justice Abella is the one jurist on the Supreme Court who has had the most impact in terms of where the Charter case law on freedom of religion has been and where it will be headed,” says University of Toronto law professor Anna Su.

But the critics remain. They decry judgments they say remove law from its stable and predictable moorings.

The criticism tends to echo that of Justice Brown and Justice Rowe in Fraser: that it’s about personal preference, not objective law. Some critics suggest she strays from her proper judicial role into the political realm.

“Ultimately, Justice Abella is not a politician who can lead a political movement,” Mark Mancini, of Advocates for the Rule of Law, a forerunner of a conservative legal group called the Runnymede Society, wrote in 2017.

In his 2019 book The Canadian Manifesto, Conrad Black called her ruling establishing a constitutional right to strike “the most astounding concatenation of juridical non sequiturs.”

He did, however, call her a friend and a lovely person.

Supreme Court of Canada Chief Justice Richard Wagner, left, and fellow judges Michael Moldaver, second from right, and Andromache Karakatsanis, right, listen in as judge Rosalie Abella responds to a question during a question-and-answer session at Canadian Museum of Human Rights, in Winnipeg, Sept. 25, 2019.John Woods/The Canadian Press

It might surprise Canadians to learn that Justice Abella’s rulings have resonated around the world. Among legal scholars, says Yale’s Prof. Hongju Koh, “Rosie Abella is really the most famous Supreme Court justice in the world.”

Her international counterparts offer useful insights into her legacy.

“She makes her colleagues … consider, in particular, the often hidden fate of women, children and others not privileged,” Justice Susanne Baer of Germany’s Federal Constitutional Court wrote in an e-mail.

“Her experiences of injustice and horror have shaped a passion for substantive justice,” says Ms. Elias, the retired New Zealand chief justice, defining “substantive justice” as “just outcomes, not just procedural or formal justice.”

Her belief that courts and judges and constitutions can change the world have also resonated.

“A striking feature, with which I also identify myself, is a belief in the transformative power of Law,” Justice Luis Roberto Barroso of Brazil’s Supreme Federal Court, noted in an e-mail.

Partly her international renown stems from her annual attendance, as the Supreme Court’s representative, at a Yale conference for the world’s supreme court and constitutional court judges, and partly from her 39 honorary degrees and many awards. Then there are her writings on and off the court, and dozens of speeches on several continents. (She even gave a speech in Jerusalem in 2018 criticizing a proposal by the Netanyahu government to give legislators an override of Supreme Court rulings. The government shelved its proposal.)

She has also left a personal mark on her international peers. When she told her family story at the Hague in 2012, Justice Baer was moved to tears. Afterward, the child of Holocaust survivors embraced the German judge, who has never forgotten that moment.

“I felt ‘adopted’ by that way more experienced and glorious judge,” says Justice Baer. Justice Abella’s hug opened her up, she says, to speak about “the humble ambivalence of being German and facing a survivor of what my people did.”

Mr. Gopnik, who grew up in Montreal, sees her as a great liberal figure. “I think liberalism is often misunderstood as a dry, procedural, rule-bound enterprise,” says the author of A Thousand Small Sanities: The Moral Adventure of Liberalism, which includes a few pages about Justice Abella. “What struck me is that the great liberal thinkers have all been people of enormous passion, whose lives have been devoted to making those passions into practical politics.”

Or in Justice Abella’s case, law.

Justice Abella's time on the Supreme Court officially ends on July 1, her 75th birthday.Dave Chan/The Globe and Mail

On the night before her final court hearing, Justice Abella stayed up till five in the morning writing some final words of farewell. A few hours later, maskless, she told her story in the nearly empty courtroom; only her colleagues were there in person.

She concluded by speaking of her parents and country.

“I say to Canada on their behalf: Thank you. Thank you for giving them the life they dreamed of, and for giving me a life beyond their wildest dreams. I am so proud and lucky to be a Canadian.”

A short walk from the court, in her apartment in Ottawa, she keeps a picture of Julius, her murdered brother. Her grandchildren, Felix and Maysie, have asked about him. She responds that he was a wonderful little boy, and she’s sorry she never had the chance to know him.

“I think of him the way I think of the millions of people killed in the Holocaust,” she says. “Not what I lost … but what the world lost.”

What’s next? Not retirement. She has appointments as the Samuel and Judith Pisar Visiting Professor of Law at Harvard Law School (three years, renewable) and as the William Hughes Mulligan Distinguished Visiting Professor in International Studies at Fordham in New York. She will also be a visiting research scholar at Yale and a visiting jurist at the University of Toronto.

Clearly she doesn’t lack for energy and gets by, even today, on just a few hours of sleep each night. “I don’t eat vegetables, and I’ve never exercised,” she adds.

As she nears 75, she is still the jurist in the sequin mask, mischievous and boundary-pushing. Still rebuking history, and still planning on watering the living tree. Still exuberant.

JUSTICE ABELLA ON...

Judges in the 1970s:

“They were intrigued by seeing a young woman in a courtroom – especially a young pregnant woman. I didn’t lose a case when I was pregnant. I think they were terrified I’d have the baby right there.”

Her husband, Irving Abella:

“I just thought he was so smart and appealing and so delicious, and he after 20 years came to see me in not dissimilar terms.” [from a public talk in 2019]

The pillars of democracy:

“Unless you think democracy only means the views of the majority as expressed in the legislature, which essentially is what an autocracy is, then you have to understand there are different players. The media are crucial. Dissent is crucial. Courts are crucial. Independent lawyers are crucial. Rights of minorities are crucial. To say that democracy is only about elections misses 200 years of democratic philosophy.”

The power of showtunes:

“I sing Broadway musicals at the top of my lungs, and I choreograph them. I dance around the room singing them.”

Former chief justice Beverley McLachlin:

“Bev had an acute sense of what the job requires: how you have to have a judicious mix of respect for precedent and a willingness, when the precedent appears no longer to be doing what it was designed to do, to change it.”

Her advice for anyone just starting out:

“Don’t start by thinking where you want to end up or you’ll miss out on the chance to take professional risks that will make you a better lawyer, a better judge, a better person.”

Limits to religious freedom:

“Not all differences are compatible with Canada’s fundamental values and, accordingly, not all barriers to their expression are arbitrary.”

Her successor, Mahmud Jamal

“He’s a wonderful choice!”

Whether she’d change any of her past rulings:

“Not one.”

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.

Sean Fine

Sean Fine