"Hannah Höch: the bob-haired muse of the men's club" – so ran one headline on the German artist's death in 1978, at the age of 88. Höch had been characterised as the It girl of the Berlin dadaists for most of her life. The obituaries also mentioned her early photomontages satirising Weimar politics, but mainly she emerged as a kind of moll-cum-waitress: lover of one dadaist, purveyor of sandwiches and beer to the others.

"Dada's good girl", with her nimble scissors and Louise Brooks haircut – this has been a hard reputation to dislodge, so much so that the show opening at the Whitechapel Gallery next week is the first full-scale survey of her work in Britain. It presents 100 montages and watercolours (and combinations of both) made over six decades, largely in Berlin, and from 1939 onwards entirely in the tiny suburban cottage in which she hid from Nazi scrutiny and which became home for the rest of her life.

"It was the ideal place to sink into oblivion," she wrote, and a very necessary oblivion for a bisexual woman whose work was not just avowedly anti-art (the slogan at the first international dada fair in 1920) but quite energetically anarchic. Höch's most famous montage remains the gleeful jamboree Cut With the Kitchen Knife Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany, 1919-20, in which the world is not just turned upside down but birled about in all directions.

Karl Marx, Kaiser Wilhelm, Albert Einstein, the dadaists themselves: this epic montage teems with dozens of faces. The body of the dancer Niddy Impekoven juggles the head of the artist Käthe Kollwitz, female acrobats leap and tumble among the soldiers, guns and plutocrats. The kaiser's preposterous mustachios metamorphose into the backsides of two wiry boxers.

It's a juggling act of bristling vitality, and though it is often praised as a great assault on German politics, the sending up of people and objects – quite literally – is what strikes. Höch's art is so balletic, her snipped images and dismembered figures dance on the page like leaves in the air. Her work is tough and punchy, yet always delicate.

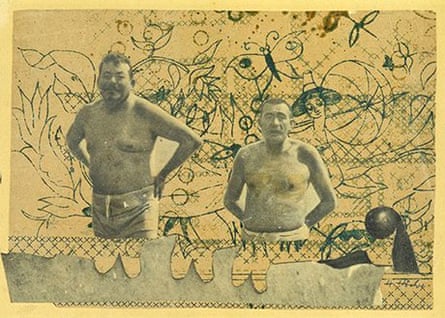

You see that in her comical juxtaposition of portly German politicians in their swimsuits floundering against a backdrop of fine embroidery that appears to catch them in its net, and in the series of collages devoted to money. In Geld, a young female arm tries to gather in a brimming column of coins, like a croupier sweeping up the chips, except that the money is gigantic. The coins are as big as bombs, and the arm has become a machine.

Like her colleagues Raoul Hausmann and John Heartfield, Höch's early work was mainly political. Photomontage was the aesthetic of liberation, revolution, protest. It wasn't just some primitive precursor to Photoshop. And in the hands of these artists it became intensely ideological, a defence in times of tyranny and a weapon against injustice. People's heads could be cut in two, their bodies deformed, their words and actions distorted.

But Höch was never doctrinaire or narrowly focused. Many of her montages make men into women and vice versa – you can trace her influence to the androgynous hybrids of Cindy Sherman – lighting upon the imbalance between the two. The Father shows a man in a fetching frock cradling a baby: so far so good; but his alter ego the boxer is throwing a punch straight at the infant's head.

In Höch's wonderfully mordant story The Painter, the eponymous artist is filled with resentment at having to wash the dishes upon his wife's request "at least four times in four years". He is dismayed that women can be so little and still not be moulded or shaped – which is, of course, Höch's own particular forte.

She is brilliant at enlarging a single feature – the huge glowering eye in The Melancholic, trapped in a tiny face looming out of the gloom; the vast hand clasped melodramatically to the breast of The Tragedienne. To model a head so that it seems to be looking in two directions at once – sweetly forwards, broodingly backwards – merely by sleight of hand and scale, is to make visible the horror of duplicity.

Höch's photomontages often have a narrative undercurrent. Love is a curious creation indeed – an odalisque in satin dance shoes reclining on a fossil while a second pair of legs plunges down on dragonfly wings – half beautiful, half sinister, old as time yet piercingly brief.

Höch had a long affair with a Dutch poet (female) and a short marriage to a German pianist (male), and words and music often appear as a kind of backdrop in her work, the landscape to her scissored figures.

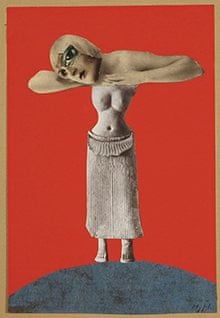

The series known as From an Ethnographic Museum fuses European bodies and African masks, black men and white women, blue-eyed boys and dark-skinned girls (montage as miscegenation). These are signs of the times. One infers a savage ridiculing of Nazi ideals of racial purity, and perhaps of western notions of beauty in general. But what is so contradictory about these montages is that they are always so elegantly made. Höch's deftness, her flawless sense of colour, tone and touch, her instinct for shape-making and balanced composition, leads to an anti-dada aesthetic – an art that is beautiful in itself.

Hannah Höch's career amounts to a collage in its own right, from the early political works to the late semi-abstract compositions; from graphic design to embroidery; from intimate portraits to archetypes to fantastical jeux d'esprit. Through it all, unlike her male counterparts, she never seems to have lost her characteristic sense of wonder, a desire "to show the world today as an ant sees it and tomorrow as the moon sees it".

It isn't quite what one associates with the cutting art of photomontage, and perhaps that has counted against her. One of Höch's self-portraits is a brilliantly acute silhouette – white out of black, it's a large but radiant blank, encapsulating her strangely unknown self.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion