Musa Mayer has been “holed up” in Woodstock, upstate New York, which she describes as “a liberal community in the midst of Trump land”, since the beginning of lockdown in March of last year. She is staying in a house she inherited from her parents and nearby is a building that was once the art studio of her father, Philip Guston. It is now the Guston Foundation, which she established in 2013 to promote his work and further his legacy. Of late, she has had her hands full.

Last September Mayer answered a call from Matthew Teitelbaum, the director of the Museum of Fine Art in Boston, one of four galleries (including Tate Modern in London) that had agreed to host Philip Guston Now, a much anticipated touring retrospective of her father’s work. It had been scheduled to open in Washington DC in July, but had been pushed back to 2021 by the pandemic. Now, to Mayer’s astonishment, Teitelbaum informed her that he and the other three museum directors had decided to postpone the exhibition until 2024. (They have since announced it will go ahead from May 2022.)

“I was just stunned,” she says. “The show had taken over four years to put together, everything was in place, the catalogue had already been published, and suddenly they had decided it was not happening.”

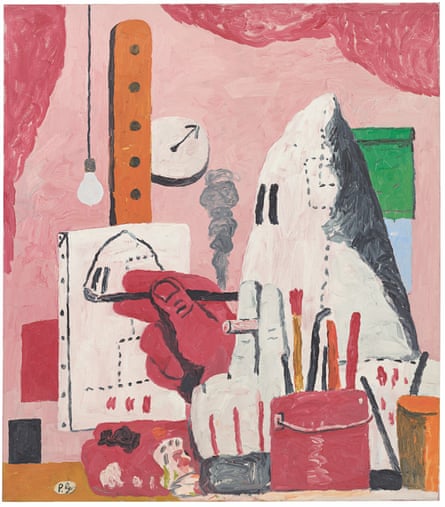

In a subsequent phone call with Teitelbaum and Kaywin Feldman, director of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, she discovered that the decision was prompted by their anxieties about a series of paintings of Ku Klux Klansmen that Guston had made in his Woodstock studio in the late 1960s. In a deliberately raw, cartoonish style, he had rendered them as absurdist caricatures of the real thing, their pointy-hooded heads an extension of their squat, sickly pink torsos, their eyes two rectangular brush strokes.

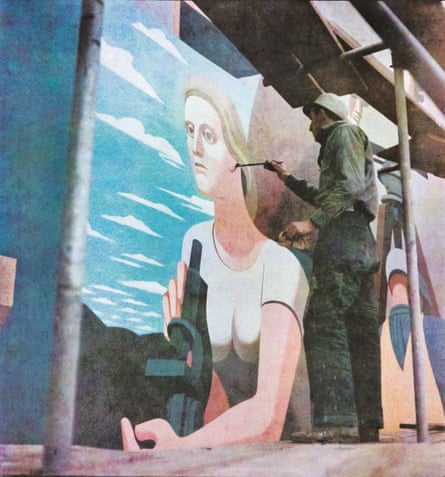

“The potent images of Ku Klux Klansmen, masked and unpunished, had lingered in Guston’s psyche since boyhood,” writes Mayer in Philip Guston, her newly published book about her father’s life and work. In 1930, just turned 20, he had first painted them in a much more straightforward figurative style for an anti-racist mural commissioned by a leftwing association in Los Angeles. It had subsequently been defaced in a raid by members of the “Red Squad”, a local police unit known to have officers sympathetic to white supremacists.

As Mayer is keen to point out, Guston’s later paintings of Klansmen, which the gallery directors deemed problematic, have been included in countless exhibitions over the last few decades without attracting adverse attention. Last September, though, in the heightened, fractious atmosphere of election year, and in the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests that erupted after the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, their potential to offend or cause pain to black visitors became the central issue for the galleries. It later transpired that it was security staff working for Washington’s National Gallery of Art who had first expressed concern about their “painful” subject matter.

On 21 September, about a week after Teitelbaum and Feldman had spoken privately to Mayer, all four museum directors issued a public statement on the website of the National Galley of Art, Washington. It began: “After a great deal of reflection and extensive consultation, our four institutions have jointly made the decision to delay our successive presentations of Philip Guston Now. We are postponing the exhibition until a time at which we think that the powerful message of social and racial justice that is at the center of Philip Guston’s work can be more clearly interpreted.” The decision, they said, was rooted in “a responsibility to meet the very real urgencies of the moment”.

The statement did little to placate Mayer’s concerns and she is still struggling to make sense of the their loss of nerve. “I was baffled by their reasons,” she says. “The issues they raised were all fully addressed in the catalogue, in which two black artists were among the many contributors who had written brilliantly about the work. Those same issues would have, or should have, been addressed in the contextualisation that was done for the exhibition. They certainly had the time to do that. I think they were simply afraid. I felt it was the wrong decision then. And I still do.”

As soon became clear in the rising clamour of protest at the decision, she was not alone. By attempting to preempt a possible controversy, the gallery directors had provoked an even bigger one that placed them in direct confrontation with most artists, curators and commentators. As Observer art critic Laura Cumming recently told me: “You would be hard pressed to find anyone in the art world who agrees with that decision.”

A headline in ARTnews – “Philip Guston Show Postponement Met With Shock and Anger” – caught the prevailing mood. Within days, the Brooklyn Rail newspaper published an open letter condemning the decision; it was signed by around 100 artists, curators, gallerists and writers. (It now has more than 1,600 signatories.)

On Instagram, an impassioned Mark Godfrey, Tate Modern’s curator of the exhibition, posted his thoughts on the cancellation. Among other things, he pointed out that, contrary to what was implied by the directors, he and his fellow curators had “re-addressed how we would present the work featuring the Klan imagery in a manner sensitive to these times”. He went on to describe the tone of the directors’ statement as “extremely patronising to viewers, who are assumed not to be able to appreciate the nuance and politics of Guston’s work”. Soon afterwards, news leaked out that Godfrey had been suspended by the Tate.

As the controversy spiralled into the mainstream, the Times published a scathing column by David Aaronovitch under the headline “The Tate is guilty of cowardly self-censorship”. This prompted a response from Maria Balshaw, director of the Tate, and Francis Morris, director of Tate Modern, in which they rebutted Aaronovitch’s accusation, but more or less admitted that the decision had been made by the American museums and they had had no real choice but to go along with it. They made clear, however, that they fully supported the decision. It had been taken, they explained, “in response to the volatile climate in the US over race equality and representation” at “a time when ‘ownership’ of representation has never been more contested”. That much, at least, is true, and they had some support from a conflicted Peter Schjeldahl, who amid a tortuous argument with himself in the New Yorker, wrote: “A time-out to recontextualize does not … constitute cowardice at a national institution.”

In America, though, two seemingly conflicting messages were emerging from the museum directors at the centre of the storm. On the one hand, a placatory Teitelbaum all but admitted that the problem lay with them, not Guston, and reiterated the need to “thoughtfully reconsider how the work could be presented”. On the other hand, Feldman told Hyperallergic magazine that Guston’s images were problematic because he had “appropriated images of black trauma”. It is worth pointing out here that, in his later paintings, Guston resolutely avoided depicting scenes of racial violence, instead presenting the Klansmen as bumbling, lumpen everymen, the very epitome of the banality of evil – white evil.

A trustee of the NGA, Darren Walker, who is also president of the Ford Foundation, a major donor to art institutions in America, went further, saying: “What those who criticise this decision do not understand, is that in the past few months the context in the US has fundamentally, profoundly changed on issues of incendiary and toxic racial imagery in art, regardless of the virtue or intention of the artist who created it.”

To Mayer’s dismay, her father, an antiracist and the son of immigrants who had fled antisemitic persecution, was now having his complex images misrepresented and their subject matter rendered simplistically provocative. “The history of racism in the United States,” she told me, “is one of periods when it is submerged in the popular consciousness, followed by periods of great unrest, like the present one, when it is manifest and no one can deny its existence. My father made those works at a time when the Ku Klux Klan were no longer as menacing as they had been in his youth, but racism was still, of course, a presence in the consciousness of mainstream white America. The paintings are essentially about white culpability – the culpability of all of us, including himself. That is why he referred to some of them as self-portraits. He wasn’t just pointing the finger at others, he was pointing it at himself. What hope is there if artists cannot examine theirselves?”

In the catalogue for Guston Now, Glenn Ligon is one of two black artists who directly engages with this prescient aspect of Guston’s work. In an essay ironically titled In the Hood, he explores the dramatic shift from figurative painting to abstraction that underpinned Guston’s later Klan images and led him, in Ligon’s words, “to explore issues of domestic terrorism, white hegemony and white complicity”. For Ligon, Guston’s Klan work challenged the unspoken idea that “living in a country built on white supremacy could leave you unmarked”. He concludes by describing Guston’s “hood” paintings as “woke”.

In another illuminating catalogue text, Trenton Doyle Hancock, a black artist whose style draws on graphic novel and cartoon imagery, addresses Guston’s early Klan paintings from the 1930s. “Just as Guston engaged historical sympathies, I have found my way to a new meaning by engaging Guston,” he writes, citing a series of paintings he made in 2016 that sprang from the question: “What if my character Torpedo Boy, a black superhero, met up with Guston’s Klansmen?”

Guston’s long journey into such complex, and resoundingly contemporary, subject matter began when he was a young man in Los Angeles in the 1920s and 1930s. Back then, membership of the Ku Klux Klan was in the millions and their hatred was not reserved for black people, but included communists, Catholics and Jews. What’s more, their threatening presence was being felt not just in the south, but in cities like Los Angeles. As the son of Jewish immigrants who had fled persecution in Ukraine, hewas a potential target for their hatred and, as a young leftwing artist, the defacing of his anti-Klan mural had been a formative experience.

Abandoning figurative painting in the late 40s, Guston built a reputation through the 50s and 60s as an abstract impressionist of the New York School, though he was not as well known as the likes of Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko or Jackson Pollock, all of whom were his friends. In 1968, when he turned away from abstraction, his decision was prompted by a period of acute self-questioning.

“When the 1960s came along,” he later said, “I was feeling split. The war, what was happening in America, the brutality of the world. What kind of man am I, sitting at home, reading magazines, going into frustrated fury about everything … and then going into my studio to adjust a red to a blue.”

Guston was particularly disturbed by television footage of the police violence against protesters at the 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago. For him, the Klan may have faded from view to a great degree by then, but many who sympathised with white supremacy were hiding in plain sight. “Unlike the images he made in the 30s, the new hooded figures did more than just refer to Klansmen,” says Mark Godfrey. “They needed to do more work for him as symbols of the extremism of some of the followers of Richard Nixon or Chicago’s mayor, Richard Daley, those who concealed their real intentions behind the mask of mainstream politics.”

Guston’s Klan paintings caused controversy when they were first exhibited at the Marlborough Gallery in Manhattan in 1970, but in a way that seems surprising now. Back then, it was their style rather than their subject matter that shocked the art world. Gone were the thoughtful abstractions that had made his name, replaced by paintings that seemed wilfully inept to many of his many fellow artists as well as the critics. The work was variously dismissed as “crude”, “simplistic”,” embarrassing” and, in a blistering New York Times review, headlined “A Mandarin Pretending To Be a Stumblebum”, Guston was even accused of being a fake indulging in radical chic.

His crime, as the art historian David Anfam would later point out, was to have “betrayed the ideals of the form in which he had made his name”. In the few instances in which Guston’s subject matter was addressed, it was judged to be almost embarrassingly passé. In a Time magazine review pointedly titled “Ku Klux Komix”, a bemused Robert Hughes asked: “Who now takes the Klan as a real political force?” Hughes went on to castigate the paintings for their political message, which, in his opinion, was “as simple-minded as the bigotry they denounce”. Though scathing, Hughes did recognise the metaphorical thrust of Guston’s hooded figures, pointing out that they were “not to be taken as symbols of a pervasive present threat, but as generalised symbols of inhumanity”.

Hughes’s take is interesting, not least because, like every other critic who panned the show, it never entered his mind to question Guston’s right to create such potentially provocative imagery. Nor did he question the gallery’s right to exhibit the paintings or their responsibility to visitors who might feel offended or emotionally disturbed by the subject matter. That, in itself, may be an index of the whiteness and insularity of the New York art world of the time. Fifty years later, things have changed, if way too slowly. Writing in the Atlantic, Shirley Li noted that, while conversations about inclusivity are nothing new in the art world, “the controversy surrounding the Guston show is one of the clearest indications yet that the national reckoning over race has permeated the country’s cultural institutions in a way that’s impossible to ignore”.

Back in 1970, Willem de Kooning was one of the few present at the Marlborough opening who grasped the full import of the work. He congratulated Guston, saying: “Do you know what the real subject is, Philip? Freedom!” When Guston recounted the story later, Musa Mayer recalls, he said: “That’s the only possession the artist has – freedom to do whatever you can imagine.”

That freedom, once taken for granted as one of the foundations of artistic expression, may be in the process of becoming unimaginable. It is being challenged most urgently by those who have long not been afforded the same platform to express themselves in an art world that, for all the conversations about diversity, is still defined to a great degree by the lack of it. Belatedly those issues are being addressed, but, as the controversy surrounding Guston’s work shows, it feels as if the art can too easily be made to carry the can for the failings of the institutions created to serve it, as well as their public, in a respectful way.

For Musa Mayer, the decision to bring forward the Guston Now exhibition, to next year instead of 2024, is heartening, but she still has concerns. “I want the show to reflect the whole span of my father’s work and to find a meaningful way to put the paintings that were deemed controversial in perspective. That needs to be done in a way that does not reduce their complexity.” She is worried, too, about the long-term effect on her father’s reputation. “Given all the publicity engendered by the controversy,” she says, “people will certainly recognise the name Philip Guston, but is that all they will know him for?”