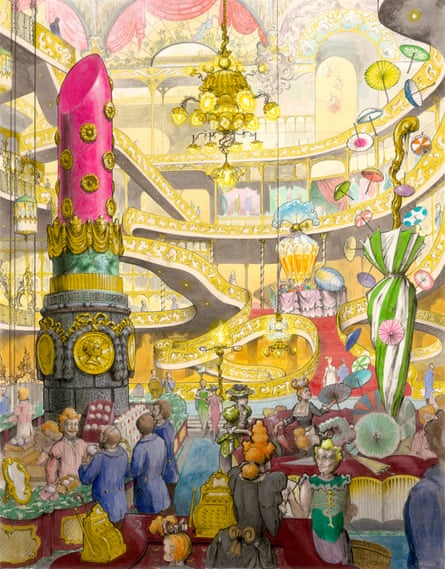

Who knew hell would be so much fun? Pink-striped cakes the size of skyscrapers teeter on gilded platters near a gigantic lobster, while masked sunbathers loll by a swimming pool, beneath an elaborate baroque diving board. Shoppers mill around a monumental statue of a lipstick, below a sweeping staircase crowned with a colossal crystal perfume bottle. Everywhere you look there are scenes of gaudy excess. It’s as if Harrods had opened a flagship store in Dubai, with Donald Trump in charge of interior decor.

This is what happened when artist Pablo Bronstein was cooped up in lockdown. Confined to his home studio in Deal, Kent, armed with dip-pen, watercolours and vast sheets of paper, the most extravagant depths of his ornament-obsessed mind were unleashed.

“I sort of lost the plot,” he says, standing in Sir John Soane’s Museum in London, surrounded by his opulent visions of hell, 22 large-scale paintings crawling with frenzied detail. “Without the usual routine of fairs and shows, I was working around the clock. When you’ve been navel-gazing for two years, you begin to lose your boundaries.”

The result is the most personal and intense body of work the celebrated British-Argentinian artist has produced to date, a self-portrait of sorts of someone who is both fascinated and repelled by the subjects of his drawings. Writhing with Frankenstein-styled architectural concoctions, which sample everything from beaux-arts and baroque, to art deco, Bavarian rococo and Viennese secessionism, the result is an indigestible banquet of bling. Brilliantly hellish, wondrously awful, grotesquely sublime, you don’t know whether to drool or run a mile. You want to be sick, but it’s hard to stop eating.

“Sometimes I’m very seduced by visual tropes, but disgusted by their content,” says Bronstein. “How do you represent stuff which you know is morally dubious, or corrupt, or evil, but which still has extraordinary beauty to it?”

Some of his answers can be found in Hell in its Heyday, an exhibition that presents Satan’s realm in the style of late 19th-century advertising posters, imagined as a showcase city strewn with garish monuments worthy of the most tasteless dictator. Taking a typically ironic stance on the last two centuries of industrial and commercial progress, the first room features mirrored casinos, palatial department stores and fantastical holiday resorts, presenting a landscape of supercharged consumption. The second room pulls back the brocade curtains to reveal the means of production, depicting the robber-baron world of coalmines, slave-powered container ships and gilded oil wells that have made it all possible. It is a riot of unbridled ornamentation, sumptuous swags heaped upon swollen scrollwork, an enamelled, gilded, bedazzled orgy of excess.

The Soane museum makes for a fitting venue. Its rooms heave with antique booty, its walls laden with similarly epic drawings of architectural fantasies that induce both wonder and horror. Bronstein took particular inspiration from the work of Joseph Gandy, Soane’s collaborator, whose visions of Pandemonium, based on John Milton’s poem Paradise Lost, seethe with an equal level of tortured overabundance. Indeed, some visitors have even asked if Bronstein’s drawings are historic – as if Gandy had dropped acid and gone wild with the paint box.

“The strong colours sort of happened by accident,” Bronstein admits. “Something went wrong with one of the red skies, and in trying to repair it I made it even more red. I secretly felt quite liberated, and worked back into the other drawings to make the colours stronger.” The happy accident has resulted in his most vibrant work yet.

In one tableau, an enamelled cement statue of Atlas in Hades crowns a roundabout, holding aloft the dome of the earth above a grotto of dancing muses, balanced on a circle of serpentine porphyry columns, swagged with a rococo caprice balustrade. This wedding cake of a traffic island stands in front of a gargantuan casino tower, striped with silver and gold mirrored glass and adorned with a fountain of Venus lactating water, ensconced in her shell beneath athletes holding globe lanterns. The infernal blood red sky burns in the background.

In another image of the city centre, elevated highways supported by decorative piers weave between an imposing central bank and a temple-like administrative building topped with a statue of Lucifer. The bank’s portico is held up on grotesquely vegetative columns, demonstrating the origins of the classical orders from plants, a caption tells us, “much like the way the central bank is as intrinsic to hell as the trunk of a tree”. The whole scene is bathed in a jaundiced yellow.

There are references throughout to the faded grandeur of Buenos Aires, where Bronstein’s family hails from, and things get more personal in the depiction of hell’s botanical gardens. Ribbons of Argentine flags hang from a delicate gazebo that frames a three-headed pink swan fountain, their necks wound into a tight spiral, garlands of roses dangling between their golden beaks. “It’s the closest I’ve come to a self-portrait,” Bronstein says, with his usual wry smile. Tropical glasshouses decorate the scene, lifted from Kew Gardens, while the gigantic dome of Nazi architect Albert Speer’s unrealised Volkshalle looms in the background. It turns out the artist is indeed present – depicted as a helpless baby being pushed in a pram through the lurid landscape.

We are plunged even deeper into Bronstein’s personal world in a room downstairs, showing a 30-minute film that was shot mostly at his home during lockdown. It sees a monstrously masked estate agent-cum-antique dealer giving us a tour of an exclusive “creativity-led apartment”, her glossy nails suggestively fondling the furnishings as she hails the “indoor landscaping by the trendiest of seating curators”. Featuring recurring themes in Bronstein’s performance work, it draws on commedia dell’arte characters, Japanese kabuki-style makeup and drag, with the artist himself providing a camp voiceover to the freakish fever dream. I made a hasty exit back to the drawings, to wallow in their sickly embrace.

The nightmarish scenes provide the perfect image for our new roaring 20s, dripping with last-days-of-empire hedonism and environmental destruction. It is an apocalyptic vision of a post-pandemic, post-Brexit boomtown, as flimsy and corrupt as it is desperately aspirational.

Pablo Bronstein: Hell in Its Heyday is at Sir John Soane’s Museum, London, from 6 October to 2 Jan 2022.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion