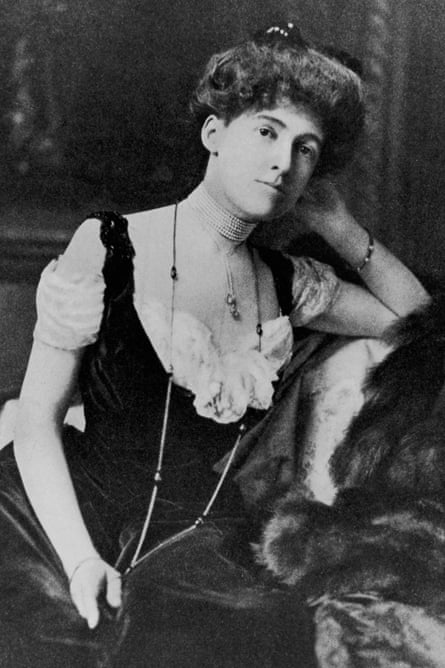

Grand and serene though the Mount looks, nestled in the woods of the Berkshire Mountains in New England, the origin story of author Edith Wharton’s former home is not a cheerful one.

When Wharton purchased the 113 original acres of the property in 1901, her mother had just died, and the chief inheritance Lucretia Rhinelander left her daughter was a fight with her brothers over the will. Wharton hadn’t yet reached the height of her fame at the time, so her funds were tight. And the construction of the house was expensive and fractious.

“The Mount,” Wharton wrote in her autobiography, “was to give me country cares and joys, long happy rides and drives through the wooded lanes of that loveliest region, the companionship of a few dear friends, and the freedom from trivial obligations, which was necessary if I was to go on with my writing.”

Wharton hired her friend Ogden Codman to work with her on building it; Codman had co-authored her celebrated 1897 book on The Decoration of Houses. But Codman was used to being Wharton’s friend, not her employee.

Worse, Codman did not get along with Wharton’s alternately depressive and imperious husband, Teddy. (“Teddy Wharton seems to be losing his mind,” Codman presciently wrote home, “which makes it very hard for his wife.”)

Relations got so bad that Wharton had to switch to another architect to get the job done. By the time she finally moved into the house in September 1902, Teddy was getting more and more unwell, descending into depression. The hope was that taking him to the Mount would keep him well enough that she could continue working.

Though the marriage eventually fell apart, the house succeeded insofar as it helped her work. While living there Wharton would write a book a year, including the Big Novel that would launch her into fame and prosperity, The House of Mirth.

The Mount sustained her in that crucial, creative period, until she sold it in 1911, after her divorce. And in the end, she remembered it fondly. “It was only at the Mount that I was really happy,” she wrote in her memoir, A Backward Glance.

Some one hundred years later, the Mount is available to anyone who wants to drive through New England to Lenox, Massachusetts. It is a kind of literary hub that’s open to the public, from March through November.

More than 40,000 people have visited so far this year, and on a recent sunny Thursday you could find about 40 people, some in groups, some alone, wandering the house and grounds. It was a picture of serenity, but it was one that has left some battle scars on the people who actually work there.

Traces of Wharton are everywhere at the Mount, in part because she built it to her own specifications, but also because of the efforts of the small band of dedicated staff, including the Mount’s executive director, Susan Wissler, who have led the fight to keep the Mount alive. It hasn’t been easy.

In 2008, in the middle of a crisis of leadership at the Edith Wharton Restoration organization that owns the house, it defaulted on the payments owed to its commercial lender. The Mount’s debt stood at about $8.5m, owed to various parties including the commercial bank that was threatening to foreclose on the house.

The New Yorker, writing about the Mount’s history shortly thereafter, was skeptical about how the money had been spent. In particular, it pointed to a $2.6m purchase of a collection of books Wharton had once owned herself, an amount the magazine said was twice their appraised value.

It seemed, for a while, as if the Mount might close. There was a public Save the Mount campaign. But then, somehow, things turned around. And two weeks ago they sent out a press release announcing that somehow, in the ensuing years, the Mount had managed to raise enough money to pay off its entire debt.

Wissler would not name the donors, but she did say that “it was a very targeted cast of about 35 individuals” who put together that money over the course of a quiet national fundraising campaign.

Wissler, a former corporate lawyer who more or less backed into a career in preserving Edith Wharton’s legacy, has brought the Mount back to solvency and emerged as a shrewd and subtle evangelist for the cause.

“The town has expressed a need for more public access to the property,” Wissler said, and clearly it’s a desire she is eager to meet.

Without any real funds to contribute while they were in the grips of their lenders, Wissler relied on outside organizations to help her maintain the vibrancy of the place. The Mount invited theater companies, prominent writers and intellectuals to come in and give talks to what turned out to be sold-out auditoriums of locals. “We see a lot of hunger, even in the off months,” Wissler said, “for intellectual content.”

Somehow the struggle fits the history of the house. It seems as if Wissler and her staff may be moving towards their own “most happy” years at the Mount. But Wissler will be the first to remind you that, “It’s not all clear sailing yet. We still do not have an endowment.” Yet then she pauses, and admits: “It still is a monumental moment.”

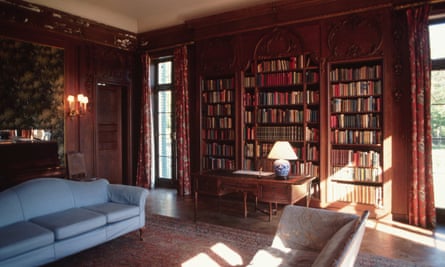

Most of the house is filled with reproductions of Wharton’s furniture, or else new items contributed by designers who participated in an earlier phase of the house’s restoration to the grandeur of Wharton’s tenure there.

But there are certain items in the house that did once belong to Wharton: specifically, her books. Nynke Dorhout, the Mount’s librarian, got starry-eyed while talking about them, holding up this volume and that to point out doodles on the end papers and interesting dedications.

And then there are the notes she made in her copy of Sages et poètes d’Asie by Paul-Louis Couchoud. Evidently this book introduced Wharton to the rhythm of the haiku, or else showed it to her in such a way that she was newly able to grasp it. For on the flyleaves, Wharton scribbled a few early attempts. She chose easy subjects, but there is a lot of delight to be found in a poem like:

My little old dog

A heart beat

At my feet.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion