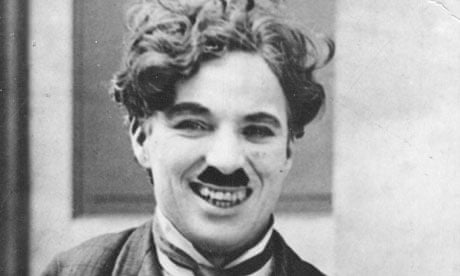

In a bomb-proof concrete vault beneath one of the more moneyed stretches of Switzerland lies something better than bullion. Here, behind blast doors and security screens, are stored the remains of one of the greatest figures of the 20th century. You might wonder what more there is to know about Charles Spencer Chaplin. Born in London in 1889; survivor of a tough workhouse childhood; the embodiment of screen comedy; fugitive from J Edgar Hoover; the presiding genius of The Kid and The Gold Rush and The Great Dictator. His signature character, the Little Tramp, was once so fiercely present in the global consciousness that commentators studied its effects like a branch of epidemiology. In 1915, "Chaplinitis" was identified as a global affliction. On 12 November 1916, a bizarre outbreak of mass hysteria produced 800 simultaneous sightings of Chaplin across America.

Though the virus is less contagious today, Chaplin's face is still one of the most widely recognised images on the planet. And yet, in that Montruex vault, there is a wealth of material that has barely been touched. There are letters that evoke his bitter estrangement from America in the 1950s. There are reel-to-reel recordings of him improvising at the piano ("I'm so depressed," he trills, groping his way towards a tune that rings right). A cache of press cuttings details the British Army's banning of the Chaplin moustache from the trenches of the first world war. Other clippings indicate that, in the early 1930s, he considered returning to his homeland and entering politics.

Most startling of all is a document that suggests we might have to revise our most basic assumptions about the man behind the moustache. After Charlie's widow, Oona, died in 1991, their daughter Victoria Chaplin inherited a bureau that had belonged to her father. One drawer remained stubbornly locked. When the locksmith jiggered it open, he found a letter in large, scrawly handwriting. A friendly note from an octogenarian called Jack Hill, who wrote from Tamworth in the 1970s to inform Chaplin that he was not one of south London's most celebrated sons, but that he had entered the world "in a caravan [that] belonged to the Gypsy Queen, who was my auntie. You were born on the Black Patch in Smethwick near Birmingham."

Chaplin's birth certificate has never been located. His mother, Hannah – maiden name Hill – was descended from a travelling family. In the 1880s, the Black Patch was a thriving Romany community on the industrial edge of Birmingham. It is not beyond the bounds of possibility that Charlie Chaplin was a Gypsy from the West Midlands.

The idea of rewriting Chaplin family history does not faze Michael, his eldest surviving son, and the man who brought Hill's letter to my attention. "It must have been significant to him," he says, "or why would he have kept it?" Perhaps a man who has been spotted in 800 places simultaneously is entirely capable of being born in two places at once.

Like the rest of his siblings, Michael is preparing for a new phase in his father's afterlife. The Chaplin family home, high on the slopes above Montreux, will soon become a museum. We walk together around its unheated spaces, progressing up the curved staircase to the room in which Charles Spencer Chaplin breathed his last. "You could say there were ghosts here," he says, as the last of the day's light drains from the air. "I think we all saw things at certain moments, but I don't know if that was him, or us, or the house. When I went to see him when he was dead, it was extraordinary. He was such a power – and suddenly, looking down at him, you could see that just the shell was there. All that was him had vanished."

Except, of course, that part of Charles Chaplin that the screen has captured for ever – and the man who might yet be conjured from the box files stored in that vault at the foot of the mountain.

Matthew Sweet presents The Chaplin Archive on Radio 4 at 11am on Monday.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion