When Mitzi Trumbo was 15, she opened her front door to find one of Hollywood’s most famous actors standing outside. It was Kirk Douglas. A few days later, Laurence Olivier turned up. “He outstretched his hand for me to shake and the dog got in the way and he tripped over.”

Fifty-five years later, she still remembers how starstruck she felt. But besides the excitement, what Mitzi most recalls from those encounters was a feeling of frustration that she couldn’t brag about it to her high-school friends. Her father, Dalton Trumbo, was one of the most famous Hollywood screenwriters of his generation, both for his work (he wrote the Oscar-winning Roman Holiday, starring Audrey Hepburn and Gregory Peck, and several novels) and for his leftwing politics.

In 1947, when anti-communist fear took root in America, Trumbo was called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee. He refused to give the names of colleagues with supposedly communist sympathies and was imprisoned for 11 months. On his release, he was blacklisted and could not work under his own name. He continued to produce uncredited scripts and his three children – Nikola, Mitzi and Christopher – were told not to speak about anything that went on at home.

When Mitzi opened the door to Douglas and Olivier, her father was writing the screenplay for Spartacus, which would go on to become one of the biggest box office hits of all time. Trumbo was publicly credited as its writer on the film’s release in 1960: an act that effectively broke the blacklist.

The extraordinary story of Trumbo’s defiance in the face of politically motivated adversity has now been made into a film, with Breaking Bad’s Bryan Cranston in the title role and featuring Helen Mirren and John Goodman.

“It’s an important story to get out there,” says Mitzi, 70, speaking from her home in the Bay Area of San Francisco. “Jay Roach [the director] and Bryan Cranston have done a wonderful job. They really care about it.”

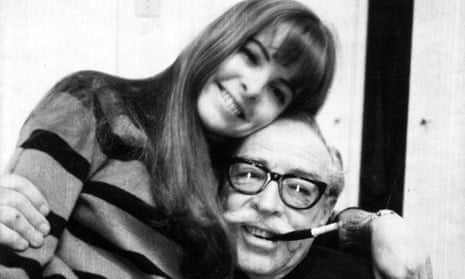

Seeing her father, who died in 1976, portrayed on screen was a surreal experience. Cranston bore a startling physical resemblance to Trumbo, “especially when they had him older. At times, I would be on set and I would say: ‘Gosh, that’s so like him.’ ”

Other aspects rang less true. “There’s a scene where he takes me and my sister for ice-cream,” says Mitzi. “I was laughing with her afterwards saying, ‘That would never have happened!’ My father worked all the time and if we had issues we went to our mum. But he was fiercely entertaining. We learned about language and politics and how to think from him. That was pretty great.”

The paranoia whipped up by the Republican Senator Joseph McCarthy throughout the 1950s had a devastating impact on many Americans unfairly accused of leftwing subversion. In Hollywood, more than 300 artists were boycotted by the studios. Some, such as Charlie Chaplin, Orson Welles and Paul Robeson, emigrated or went underground.

It was a divisive period where loyalties were questioned and friendships shattered. Trumbo, who had joined the Communist party for five years in 1943, was part of the Hollywood Ten: a group of screenwriters and directors who refused to testify and were found guilty of contempt of Congress. Other witnesses called in front of the committee – including Elia Kazan, the director of On The Waterfront – named names and were allowed to continue their work. The playwright Arthur Miller, who had been lifelong friends with Kazan, never spoke to him again. When Kazan received an honorary Oscar in 1999, many in the audience refused to clap.

Mitzi remembers her father being “pretty stoic” about his blacklisting. “He just knew he had to figure out what to do. I have to say, honestly, communism was not very important to him … He hated meetings. He was really an independent thinker and group activities were not his sort of thing. It was the principle of democracy he was fighting for, for justice and civil rights and all those things. Having all of that around you is a good way to grow up.”

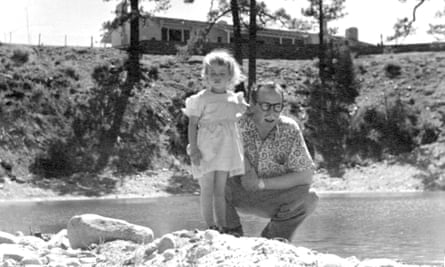

After he was released from jail, the Trumbo family escaped the increasingly uncomfortable political climate in America by moving to Mexico City for two years. Mitzi was six and had to learn a new language: “It was a big turnaround.” She credits her mother, Cleo, with “keeping us all together. She was the rock of our family.”

When Mitzi was eight, the Trumbos returned to the Highland Park area of Los Angeles.

“You knew you were different from everyone in the neighbourhood. There were many things you could never say or talk about. We could never talk about what our father was writing, even though our parents were very open with us.”

During this time Trumbo wrote The Brave One (1956), which received an Oscar for best story credited to “Robert Rich” – a name borrowed from a nephew of the producers. His earnings dwindled: over a two-year period, Trumbo wrote 18 screenplays at an average fee of $1,750 each.

At school, Mitzi felt like an outsider. “At some point, they started having secret PTA meetings excluding my mother,” she says. “Then the kids started avoiding me. It was a tough few months until I finally told my parents and said ‘I just can’t go back’. The kids tortured me for the rest of the year and then I went to a different school.”

The effect of the blacklist on families is often overlooked. In most cases, it meant that the main breadwinner was, at best, facing a substantial cut in salary and, at worst, unable to work at all. And then there was the added pressure of carrying around a notorious surname linked with communist sympathies in an era of heightened popular anxiety about the threat from Russia.

“When you said your name in the 50s, it was almost like a challenge,” says Mitzi. “Over the years it changed. Now, I get ‘Oh, are you related to Dalton Trumbo?’ ”

She says that as a result she has a special bond with the other children of blacklisted artists, particularly the family of Ring Lardner Jr, who was also part of the Hollywood Ten and who went on to write M*A*S*H. “There is a community,” she says. “There always is a feeling, even if we don’t see them often or know them well, that we know what we went through.”

When McCarthy died in 1957, Mitzi remembers “a sense of joy because he represented the whole thing”. But it wasn’t until the 1960 release of Spartacus, directed by Stanley Kubrick, and Exodus, directed by Otto Preminger, that Trumbo was given public credit for his work on both films. The blacklist rapidly lost credibility.

Mitzi remembers her parents taking her and a friend to a “fancy Hollywood [movie] theatre” on the day Spartacus was released. “It was the first time I saw his name on screen,” she says. “It was amazing. It was very cool.”

Was her father emotional?

“No, but he didn’t show emotions much. He was fierce and angry about the blacklist and when it was finally broken for him, it wasn’t broken for his friends. There wasn’t a feeling of ‘Oh, now it’s over’ because it still wasn’t for lots of people.”

Trumbo’s career survived and flourished. He was reinstated in the Writers Guild of America, and was credited on all subsequent scripts. In 1975, a year before he died, he was officially recognised as the rightful winner of the Oscar for The Brave One and was presented with a statuette.

Mitzi went on to become a professional photographer. She and her husband Richard have two daughters and two grandchildren.

As for the blacklist? It’s in the past. “Holding grudges so many years later? My parents taught us not to do that.”

Trumbo is being released in the UK on 5 February.

THE MCCARTHY ERA

■ Between 1946 and 1952, the number of FBI agents rose from 3,559 to 7,029, as part of President Truman’s loyalty-security programme, which investigated government employees to identify communist sympathisers.

■ In October 1947, the House Committee on Un-American Activities (Huac) began to subpoena screenwriters and directors to testify about alleged communist links.

■ The Hollywood Ten, a group of actors, screenwriters and directors who refused to answer some questions posed by the committee, were blacklisted by studios.

■ Eventually, hundreds of artists were banned by the industry. Among them were Charlie Chaplin, Orson Welles and Paul Robeson.

■ Senator Joe McCarthy launched his anti-communist campaign in 1950, when he accused more than 200 state department staff of being communists.

■ By 1959, Huac was being denounced by former presidentTruman as the “most un-American thing in the country today”.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion