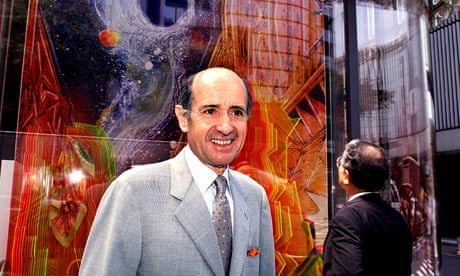

There was a single narrative of luxury in the 1980s and 90s, and its storyteller was the aggressive businessman Bernard Arnault, who aggregated the LVMH brand that corporatised many of Europe's makers of costly goods, champagne, perfume, luggage and couture. Of the few who withstood Arnaultisation, the staunchest was Jean-Louis Dumas, chairman of Hermès, who has died aged 72.

Dumas was the great-great-grandson of Thierry Hermès, who founded the saddle and trappings supplier in 1837. His mother was an Hermès, his father co-opted into the firm as president, and Dumas and his siblings were brought up in the culture of luxury, their family shops selling the famed handbags and scarves. He recalled: "We would all gather round the lunch table and my father would talk – 'that-beautiful-silk-scarf-please-don't-eat-with-your-hands' – that sort of thing."

But Dumas did not want to be subsumed into Hermès. He did his national service in Algeria, studied law and political science, travelled the hippy route – Iran, Afghanistan, Nepal – in a Citroën 2CV, drummed across Europe with a jazz ensemble. Then he spent a year taking the Bloomingdale store's buyer training programme in New York, which taught him that there was dignity in being a merchant. He joined Hermès in 1964, then became head of manufacturing. His love and respect for craft never diminished. "The world is divided into two," he said. "Those who know how to use tools and those who do not." When he gained power, he would take his artisans travelling to meet craftworkers in traditional cultures.

He became managing director in 1971; then, to his surprise, the family voted him chairman after his father's death in 1978. At that time, Europe's luxury suppliers seemed dowdy beside Paris couture, which had reinvented itself as a performance art to advertise designers' perfumes and retail lines. At Hermès, stagnant sales forced a temporary closure of the workshops. Dumas never wanted to accelerate the slow handwork of leather goods, especially not the weeks of selection of skins and their sewing. But he did want younger, chic customers, and more of them, so he asked a friend who worked at the ad agency Eldorado what he thought, and the friend answered that: "Hermès wasn't for anybody who was considered a trendsetter." Change the image, replied Dumas, and Eldorado did.

A long-established Hermès handbag, named in the 1950s for Grace Kelly, was suddenly available in bright ostrich skins, provided the buyer was prepared to wait the ritual aeon for delivery, while 1979 French magazine ads showed a rock chick accessorising her denim jacket with an Hermès scarf. The materials for change were on the premises, after all – Eldorado had noticed that the photographer Helmut Newton was fond of Hermès for its leathers. Newton called its flagship store, on the Faubourg St Honoré, Paris, "the most luxurious sex shop in the world", and, in 1976, had misused its equine merchandise in an outrageous Vogue sequence.

The head of the US store Neiman Marcus said that Dumas "revolutionised the market for Hermès by repositioning the products without changing the quality". Dumas widened his market to Asia and the Americas, while closing franchise outlets and reclaiming distribution rights. "We have enough money to finance our own growth," he said. He had nerve and kept it, choosing new designers for the firm's clothes: in 1980, he gave the 19-year-old Eric Bergère, straight from fashion school, a senior job; in 1997 he hired the unconventional but craft-fluent Martin Margiela as creative director; and when Margiela departed in 2003, replaced him with the fearless Jean-Paul Gaultier.

By then Hermès had a 35% stake in Gaultier's own house, part of an expansion that began soon after Dumas became chairman, pre-dating Arnault's acquisition of luxury makers during the 1980s. Arnault bought what had often been family firms that had potential to be marketed widely as brands; their management structure was made corporate. The goods, where and how they were made, mattered less than the label and profits. Dumas merely took stakes in suppliers (to ensure, for example, the quality of twill for printed scarves and brocade for ties), then invested in the glassware company Saint-Louis, the tableware makers Puiforcat, shoemakers John Lobb and Leica cameras, making modest demands on their profitability. He always carried a Leica to grab sympathetic shots of natural and manmade pattern and texture (and a collection of his pictures was published in 2008).

Hermès might outsource details such as scarf-edge handrolling to Mauritius, but the core workshops were purpose-built in 1991 in the Parisian suburb of Pantin and employed artisans who had served an apprenticeship. Dumas found label worship risible, believing that objects should fulfil their purpose and have personal meaning. He sat next to the actor Jane Birkin on a flight in 1984, and when papers slithered out of her appointments diary, took it back to the workshop to stitch on a pocket. She also wished for a proper carry-on carry-all bag, so he adapted a traditional Hermès satchel, sent her the proto- type, and named its commercial offspring after her. "Nothing changes, but everything changes," was an Hermès advertising slogan.

The company did not have to satisfy shareholders until Dumas took it public in 1993, and even now 72% of the shares remain in the family. It is valued at $14bn and turnover, $2.5bn last year, held steadier after the 2008 financial crash than that of the mass-luxury conglomerates: 40% of Hermès sales are leather goods, and long waiting lists for bespoke bags tided the workshops through the initial slump.

Dumas retired in 2006 as his health declined with Parkinson's disease. His wife Rena Gregoriadès, an architect who designed the firm's stores and the Pantin atelier, died last year: their children Sandrine and Pierre-Alexis (the Hermès artistic director) survive him.