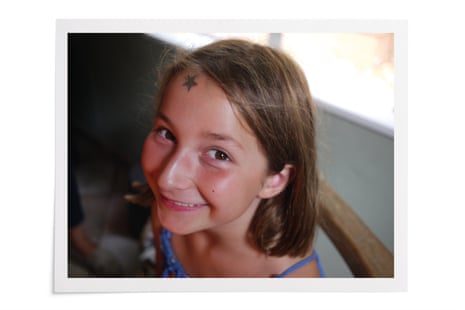

At the start of last summer, my 13-year-old daughter Martha was busy with life. She’d meet her friends in the park, make silly videos on her phone and play “kiss, marry, kill”. Her days were filled with books and memorising song lyrics. She’d wonder aloud if she might become an author, an engineer or a film director. Her future was brimming with promise, crowded with plans.

By the end of the summer she was dead, after shocking mistakes were made at one of the UK’s leading hospitals.

What follows is an account of how Martha was allowed to die, but also what happens when you have blind faith in doctors – and learn too late what you should have known to save your child’s life. What I learned, I now want everyone to know. In a small way, I hope Martha’s story might change how some people think about healthcare; it might even save a life.

I am a fierce supporter of the principles of the NHS and realise how many excellent doctors are practising today. There’s no need for the usual political arguments: as the hospital in question has confirmed to me, what happened to Martha had nothing to do with insufficient resources or overstretched doctors and nurses; it had nothing to do with austerity or cuts, or a health service under strain.

No matter how many times I’m told that “it was the doctors’ job to look after Martha”, I know, deep down, that had I acted differently, she’d still be living, and my life would not now be broken. It’s not that I think I’m to blame: the hospital has admitted breach of duty of care and talked of a “catastrophic error”. But if I’d been more aware of how hospitals work and how some doctors behave, my daughter would be with me now.

As another bereaved parent told me, life after the death of your child is like being on an island, separate from the mainland where the “normal people” live. You so badly want to go back there but you never can. You’re stuck on the island for ever.

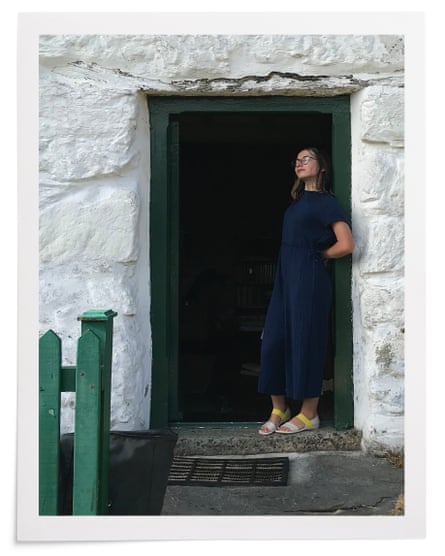

I had booked a cottage on the outskirts of Snowdonia national park. It was a small, old farmhouse with low-slung beams and no wifi or phone reception; parking was at the bottom of a hill on which sheep grazed. We ferried our bags to the door in a wheelbarrow, which Martha and her younger sister, Lottie, wanted rides in, too. Our first day was sunny: we went bodyboarding on Barmouth beach and Martha and I painted the valley view from the cottage. We had a meal in a pub, played cards – everything was holiday-easy, filled with light.

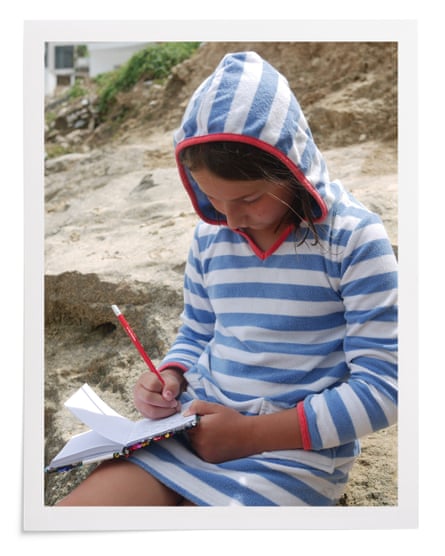

On the second day, we rented bikes and set out on a well-known cycle path: nine miles of old railway line, to the beach and back. A guide to the area described the route as “scenic, flat and family-friendly”. On the way, Martha rode alongside me and I remember we talked about body hair (she wanted to know if she should shave her armpits). We swam in the sea, ate crab sandwiches and chips. But soon after we started back on our bikes, Martha slipped on a patch of sand that had blown from the beach on to the path. She was cycling slowly – “Captain Sensible” was our nickname for her – but she fell, and was soon making the zombie sounds of someone badly winded.

The path was busy with other cyclists, so she crawled to the edge. As we waited for her to recover, another family with a much younger child cycled by. This girl also skidded on the sand but wobbled and stayed upright, so the family continued on their way. No doubt they will never think of that moment again.

Martha felt no better, so we took her to a minor injuries unit. When she raised her T-shirt for examination, we saw a red ring on her stomach: as she fell, she had landed with the full weight of her body on one end of her twisted handlebars. There was no blood or cut, only the O-shaped mark.

The nurse described the injury on the phone to a doctor who said he didn’t need to see Martha – it was probably internal bruising – and prescribed paracetamol. I wondered whether to make a fuss and insist the doctor look at her; I didn’t and we went back to the cottage. But by 2am Martha was sick and in pain, so we decided we must take her to A&E. “I can’t make it down the hill to the car,” she said, but Paul, her dad, pushed her in the wheelbarrow, trying to navigate the bumps while Lottie held up a phone as a torch. We manoeuvred Martha into the car as gently as we could.

At Bronglais hospital in Aberystwyth, they agreed to run tests and keep her in overnight for observation. I still imagined this was just a precaution, but at dawn a doctor with a serious expression told us that Martha probably had pancreatic trauma: she had fallen with such force that her pancreas had been pushed against her spine, causing a laceration.

I knew immediately that the injury was serious, but had absolute faith in the system. Two years of Covid had seen us talk endlessly to the girls about how lucky we were to have the NHS. Martha and Lottie painted rainbows with the words “Thank You” and put them in our window. For a few weeks we stood outside the door on Thursdays and joined the communal clapping; Martha banged a pan with a wooden spoon.

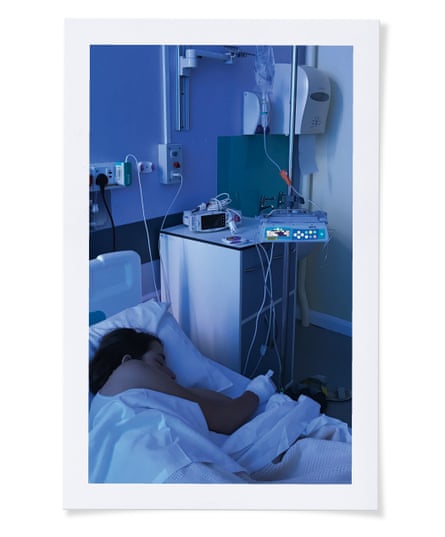

I was so confident in her recovery that I started taking photos – they would be props when she told the story of her summer misadventure. The first captures her curled asleep in the blue wash light of her Aberystwyth hospital room. In the next, she is outside the helicopter that took us over the Brecon Beacons to the University Hospital of Wales in Cardiff. The paramedic is leaning over her shoulder and they are both giving a cheerful wave to the camera.

At Cardiff, Martha was taken to intensive care and hooked up to the kind of bleeping monitors I knew only from TV dramas. She had one-to-one nursing – a nurse was with her all the time, standing behind a kind of lectern at the foot of her bed. None of us had been hospitalised before and I was frantic, but one of the doctors gripped me by the shoulders: “It’s going to be a tricky couple of days – but she’ll be fine.”

I was already Googling. Pancreatic trauma, in adults, is usually seen alongside other organ damage in victims of car crashes or shootings: I thought of the “O” on her stomach – a bullet wound without the bullet. In children, it’s most often associated with bike injuries – BMX jumps and stunts gone wrong. What matters is identifying the injury quickly, before corrosive juices escaping the pancreas cause too much damage. I was so relieved we’d made our middle-of-the-night dash to the hospital.

From Cardiff, Martha was helicoptered to King’s College hospital in London – one of three specialist centres in England that deal with pancreatic injuries in children. There she was installed on Rays of Sunshine ward which, as the nurses told us, is well funded, through a combination of NHS money, donations and the fees of private patients who come from around the world.

Martha had a glass cubicle with a TV; the ward had new equipment and a playroom – some children, including liver transplant patients, stay there a long while. “You are in the best place,” we were repeatedly told. Plastered around the walls were posters for the Great Hospital Hike – a September fundraiser for King’s, which I resolved to sign up to, in thanks. “We are so lucky to be here,” Paul and I said to each other.

It turned out, however, that Martha was cosmically unlucky. Her injury was treatable: she became the first child on record at King’s to die of it – after the care for her became careless. Her preventable death is an example of what a hospital official described to us, in a barbarous phrase, as a “poor outcome”. I will spend decades asking: why was my child the one to suffer such an unlikely fate?

I became pregnant with Martha at the age of 29 and it all happened so fast I wasn’t sure it was the right thing. I loved my job, I was enjoying life – the parties, the freedom. I worried I might be too selfish to be a parent, that a baby might cramp my style. But when she emerged, battered and bruised from being round the wrong way inside me, I was instantly changed. As I told a friend at the time, I felt I had been punched in the face by love.

She was such an easy baby, people told Paul and I we were great parents. Naturally we took the compliment, but the truth is she just came out that way – sanguine and content. “I’m as jolly as a jolly-bird,” she used to say when young, and that summed up her temperament nicely.

On Rays of Sunshine, Paul and I would take turns to spend 24 hours at Martha’s side, sleeping next to her on a foldaway bed. We were told every day that her recovery was never in doubt: it was just a matter of time and patience. After a fortnight, she was walking down the corridor and friends came to visit. One doctor told her: “I’m going on holiday, and I hope not to see you when I’m back.” We got used to the routine on the ward: nurses taking observations, the early morning blood test, the travails of the boy in the next-door cubicle who also had pancreatic trauma from a handlebar accident. We put pictures of our cat on the cubicle walls.

I grabbed snacks on the ground floor of the hospital. On my way down there one day, I saw two women shouting in rage. “Fackin’ murderers,” one screamed, her hands cupped around her mouth. She wanted everyone to hear. “Let’s get away from the fucking killers,” shouted the other, as they headed for the exit. I recoiled, and instinctively took the side of the doctors.

Martha was nil by mouth and given milky formula through a tube up her nose. With no meals to break up the tedium of hospital days, she would stare longingly at pictures of lasagne and roast potatoes on her phone. On the breaks from her milk feed, I’d run her a bath and mix in bath salts from home to give her a hit of luxury. She’d soak in the tub and her brown hair would fan out behind her in the water – the tips blond where I had dip-dyed them at the start of the summer. I’d wash it for her, as I did for so many years when she was young.

We often saw a different consultant each day, and now and then would wonder who had overall responsibility for Martha’s care: I wish now we’d done more than wonder. Every morning, during the ward round, we’d ask the consultants questions about how the treatment worked. We tried to be articulate and grateful – these were the experts and we wanted to bring out the best in them. It turns out we were judged in the medical notes: “Mum and Dad pleasant and helpful,” reads one entry.

The consultants swooped in, and were ostentatiously deferred to by the junior doctors. They were chatty, assertive, grand. We heard about a research paper one especially self-regarding surgeon – I’ll call him “Prof Bow Tie” – was due to give in Athens; he posted the view from his luxury hotel on Instagram a couple of days after Martha died.

Following the ward round, Martha was looked after each day by junior doctors. They seemed young, but carried themselves with confidence, so I assumed they knew everything about Martha’s care. I was so naive I didn’t even realise they were training.

Among the Get Well Soon cards and gifts sent to Martha was a reversible toy octopus that could be flipped to have a happy or sad face: she began to use it to mark her good and bad days. A few weeks into her time on the ward, on the weekend of 21-22 August, she developed a fever. The octopus was frowning and Martha said she was scared. For the umpteenth time, I praised her bravery and promised her there’d be another side to this. “This is a great hospital,” I told her. She lay shivering, had constant diarrhoea and would retch, spitting the nothingness in her stomach into cardboard bowls we’d hold under her face.

The doctors prescribed antibiotics and said they would get rid of the infection within 72 hours. “What happens if they don’t work?” Martha asked. “They will,” she was told. “But what happens if they don’t?” “They will.” We gave her ice-packs for her temperature and hot-water bottles for her back pain. She’d wander into the corridor to stand under the air conditioning vent, dropping her head backwards so she could feel the rush of cold on her face. I would put my arm around her shoulders to guide her back to bed.

Short-lived infections, we knew, could happen during her treatment. But on Wednesday Martha’s fever was still there. And something else, even more worrying: she started to bleed from both the line in her arm and the tube from her abdomen. The blood oozed through her bandages and soaked through her pyjamas and sheets. This bleeding, we found out after she died, is very rare for her injury and a recognised sign of severe sepsis.

While the doctors knew she had sepsis, they never used that word when talking to Paul or me – just “infection”. I wish they had, because I would then have found out more. I was told merely that Martha’s “clotting abilities were slightly off”, which was “a normal side-effect of infection”.

Hospitals use a guide to help doctors and nurses decide when to raise concerns about child patients, called BPEWS – it stands for Bedside Paediatric Early Warning Score and involves heart rate, temperature, blood pressure and other measures. We later found out that on Wednesday Martha’s BPEWS was six – a high score – and that there should have been a discussion about transfer to intensive care.

But Martha stayed on the ward and carried on bleeding. The medical notes say I was “very distressed”, but all the doctors told me she’d “turn a corner”, and of course I wanted to be reassured. A scan showed a small amount of fluid around her heart – another sign of sepsis, we later discovered. Action was delayed until after the bank holiday weekend and we were told nothing about it.

Severe sepsis is most often dangerous when patients don’t make it to intensive care, where it can be treated with powerful drugs and frequent interventions. Martha could easily have gone to paediatric intensive care (PICU), which was just down the corridor and had beds free. But her consultants preferred not to involve PICU.

Living with a child for 14 years, they become a part of you: a year after Martha’s death, it’s still so hard to break the lovely habit of her. I think of her unwrapping an ordinary present of underwear: she shouted “Knickers!” and threw them up in the air to land on our heads. Her laugh was a gift: there was nothing to match her collapsing into giggles, head thrown back, clutching her stomach.

She enjoyed cutting her dad down to size, and would tease him about the time he cycled his bike into the canal. A romantic, she loved to hear the tale of Paul and I getting engaged. And there was her cello playing, and the songs she wrote, her poems. She mapped out a whole novel at the beginning of the summer, and her notebooks were full of ideas for stories (“The Story of Nothing”: “Every book starts with nothing. But in this case, Nothing is a boy. And this story is how Nothing turns into Something … ”)

At Martha’s memorial, a school friend of hers said: “For me, there were two sides to Martha – the person who danced with me on the train platform; the one who had fun, sassy arguments in American accents with me; the one who would put a PE bag on her back and call herself a turtle. Then there was the one who quietly sang while I rested on her shoulder on the train home. She would always be there for me, and I would be there for her, too.”

The doctors gave Martha lots of clotting products and her bleeding finally stopped on Friday morning. Yet as early as lunchtime she was in tears about her ongoing fever. She no longer wanted to read – she always read – or play Minecraft with friends on her phone. A fan of Lin-Manuel Miranda, she showed no interest when I suggested we watch his new film.

The doctors didn’t know the source of the infection, and the bank holiday weekend was approaching. On weekends, the ward took on a different atmosphere – the corridor was eerily quiet and after ward round the consultants went home, on call. An extended weekend and a persistent fever seemed a worrying combination.

At this point, we made the link ourselves between infection and the worst-case consequence – septic shock, a leading cause of hospital deaths. I searched out that day’s consultant and said: “I’m worried Martha is going to go into septic shock on a bank holiday weekend and none of you will be here.” The consultant ran her finger down a screen of numbers. “I’m not worried about sepsis,” she said. When I went back to the cubicle, Martha looked at me with narrowed eyes. “I heard you talking about septic shock.” “Don’t worry, my love,” I said. “I just need to make sure they’re thinking of everything.” The consultant’s parting words as she left were: “It’s just a normal infection.”

I was reassured again when the businesslike, blase head of the team of consultants told Paul on Saturday morning: “This is what it’s like with this injury – infections come and go.” But Martha’s fever continued and later, when she tried to stand, she felt very light-headed and dizzy. Paul told the junior doctors: “This is new.”

On Sunday of the bank holiday weekend I was with Martha. I recall that day’s ward round, when the consultant – I’ll call him “Prof Checked Shirt” – talked in hushed tones with a surgeon outside Martha’s cubicle. We later found out that she was much worse than they were expecting. But they revealed nothing of this to me and I saw neither of them for the rest of the day. Martha was left in the hands of two junior doctors, one – the registrar, whom I’ll call “Dr Blunder” – more experienced than the other.

Prof Checked Shirt – an Oxford-educated man in his late 50s with an air of supreme confidence – left for home early in the afternoon. In his absence, when on call, he was to play a pivotal role in Martha’s death. By lunchtime, she had unexplained sepsis, a high fever, very low blood pressure and a racing heart. King’s later produced a Serious Incident report into why Martha died and its writer told me that she should, at this time, have been moved to PICU.

But Prof Checked Shirt, in charge that day, didn’t once consider such a move. Tellingly, the report revealed high-status consultants on Rays of Sunshine (“level sevens” in the ranking of seniority) had a dismissive attitude to less senior colleagues in PICU (“level fives”). This made them reluctant to do the right thing and involve intensive care: Martha died in part because of inflated egos.

Then, early on Sunday afternoon, she developed an angry red rash; it spread across her legs and neck and torso. A rash is a red flag for sepsis. Yet Dr Blunder – headstrong, with no experience of this kind of situation and despite Martha’s other symptoms – somehow convinced himself that the rash was caused by a delayed drug reaction. I made clear to him my anxiety that it was a sepsis rash, but it made no difference.

I left Martha’s cubicle to look for an ally and grabbed a nurse: we walked down the corridor together. “I’m worried he’s got it wrong. I’ve been trying to look it up online.” The nurse stopped walking and put her hand on my arm. “Don’t look things up on the internet,” she said, “you’ll only worry yourself. Trust the doctors – they know what they’re doing.” I followed this advice. It turned out to be the worst I will receive in my whole life.

Martha had an unshowy confidence that I admired. By the time she got to secondary school, she hadn’t worn a skirt for a couple of years and I was aware that, while trousers were an option for girls, nearly all of them wore skirts. I wondered how she would cope. “Should I buy you an insurance skirt just in case?” I asked her. “No,” she said, “just the trousers.” When she met fellow students before the first term began, they stood comparing notes. “We’re going to wear skirts, right?” “Yeah, skirts, definitely.” I watched Martha out of the corner of my eye as they all agreed. “I like trousers,” she said, quietly. She wore trousers and before long, others did, too.

Martha never got to have a first kiss. She was good friends with a boy in her class, who used to find it funny that her favourite word was “defenestration”. There was another boy she was keen on, but we never got to see how that played out. In the hospital, she and I had a chat about gender and sexuality. I asked her, “Do you ever think you might be gay?” She said: “I’m pretty sure I am straight. But who knows – maybe I just haven’t met the right woman yet.”

Dr Blunder’s misdiagnosis of the rash was described as “such a mistake” by the coroner at the inquest into Martha’s death. Even unpressured clinicians make errors, though rarely ones so glaring and cataclysmic. But I’m still mystified about what happened next.

At 5pm, Martha had a score of eight on the BPEWS chart. We weren’t told, but Dr Blunder phoned Prof Checked Shirt, at home, to tell him. The consultant didn’t consider coming in. Though he admits he wasn’t at all sure Dr Blunder’s diagnosis was correct, he failed to suggest the rash might be caused by sepsis. Dr Blunder spoke to him again later, but it was felt no change in Martha’s care was needed. Because of the strict hierarchy that exists in hospitals, no one on the ward took the initiative. She wasn’t moved.

When Prof Checked Shirt made his routine call from home that evening to the head of PICU, he painted only a partial picture of Martha’s condition. He did not mention her previous bleeding or the fact that the rash she had was new. He was relaying her details “for information only”; intensive care “categorically” should not pay Martha a bedside visit, he said: “no review was needed” and it would increase my anxiety. The hospital’s policy dictates that parents being worried is a reason to escalate; he decided the opposite.

The head of PICU could reply only that there was a bed available if needed. He was asked at the inquest whether, had he been given the full picture by Prof Checked Shirt, Martha would have been moved to intensive care. He answered: “Without a doubt, 100 per cent.”

After Martha’s death, Prof Checked Shirt was very reluctant to use the word “mistake” to describe his actions, though his error had been identified by colleagues. Other consultants were also at fault: the hospital report concluded that on at least five occasions Martha’s care should have involved PICU. Yet at no stage did any doctor let me know that she was in real trouble. I was kept in the dark and condescended to. The focus on my – justified – anxiety reeks of misogyny.

And, unbelievable as it seems to us now, neither Paul nor I knew that intensive care was the right place for Martha to be. We didn’t know enough to argue, to challenge, to insist that she should be moved there. So we ended up failing to fulfil the most essential duty of parents – to protect our child when she was in danger. The guilt will always be with me.

That evening shift brought a new junior doctor, who worked alongside Dr Blunder. It was made clear to her that Martha needed “constant monitoring”. (After Martha died, the notes from this vital handover mysteriously disappeared from King’s computer system.) It was decided not to perform a vital blood test – who knows why; doing so could easily have saved Martha’s life. An instruction that she should have one-to-one nursing failed to get carried out.

What’s more, this junior doctor (“Dr Do-Nothing”) didn’t once walk down the corridor to visit Martha, to set eyes on the ward’s most critically ill patient, even though the nurse passed on worrying observations.

I promised Martha yet again she’d get through this. “You’ve said that so many times it’s become meaningless,” she said. Throughout that night, her thirst was unquenchable. “Water,” she gasped at regular intervals. I refilled bottles – but she couldn’t seem to get enough. “She’s drinking crazy amounts of water,” I told the nurse, more than once. I was exhausted and didn’t realise this was yet another sign of disaster. Still, Dr Do-Nothing decided it wasn’t worth walking a few metres to see my daughter.

At 5.45am, Martha told me she needed the toilet. But as she moved to sit down, her body stiffened and her eyes rolled back in her head. I caught her as she started fitting and convulsing. Her body jerked in my arms and I was barely able to hold her weight as diarrhoea poured out of her. Sepsis happens when the body overreacts to an infection and damages its own organs and tissues: the seizure was caused by not enough blood getting to her brain.

I now panicked for the first time and started screaming: what is wrong with her? After a few moments, she came round and the nurses fussed over her. In tears, I corralled the senior nurse who told me of course my daughter wasn’t going to die and that I should pull myself together. I washed my face and returned to the cubicle. Martha and I were alone together when she hovered her hand above her torso and looked at me with fear in her eyes and quietly said: “It feels like it’s unfixable.” At night, these words wake me in a surge of terror and panic.

It was only when the blood test was finally done that Dr Do-Nothing woke up to the fact that her patient was dangerously ill. Martha was taken to intensive care, but arrived there too late to break the cycle of septic shock. That evening, there was a last-ditch transfer to Great Ormond Street children’s hospital for Martha to be attached to a machine that would act as heart and lungs outside her body. But it didn’t work. Martha died in the early hours of Tuesday morning.

I could write pages about the horrors of that last day. Let me simply describe her move out of Rays of Sunshine, the move that should so obviously have happened before. Martha’s cubicle was suddenly filled with purposeful PICU clinicians. “Please make sure she’s better by Saturday,” I said weakly. “It’s her birthday.” Once in intensive care, Martha had an oxygen mask clamped to her face, but she thought it was an anaesthetic that should be putting her to sleep. “This isn’t working,” she said, pointing at the mask. I tried to tell her it was oxygen but I’m not sure she heard. Within seconds they forced a tube down her throat; she gagged and her back arched before the strong sedative took hold. I love you, I love you, I love you I said over and over. And suddenly Martha was in a coma from which she would never wake up.

I know many of the details of Martha’s deterioration because of the report, the questions we have put to King’s since her death, and the inquest, which concluded that her doctors failed to heed the warning signs and move her to PICU. Hospitals have a “duty of candour” – they are supposed to be transparent about mistakes made. In our case, King’s behaved much better than some, but there were obvious limits and important questions were left unanswered.

The hospital trust issued an apology but kept its legal team close. Improvements were identified – necessarily so – which is why everyone at King’s was more comfortable talking to us about “systems” than the crucial actions of particular clinicians. The trust closed ranks and we entered the familiar, enervated world of institutional condolences and “lessons to be learned”. A hospital will do what it can to protect its doctors from the tragedies they cause.

After all, how could they ever comprehend the consequences? Their lives continue while mine has stopped. (Dr Blunder was promoted to consultant within a week of Martha’s death.) Each day, I experience wave after wave of nausea, misery and disbelief. Although my father died when I was 10, I never understood grief until now. I know many people walk around in shadow, “normal” life a pale memory. But I would be dishonest if I didn’t admit to thinking about how deaths are different, and grieving is different, too.

I can’t stop dwelling on the fact that Martha’s was a preventable death (one of 150 in the NHS every week). Our culture may talk more about grief these days, but most people prefer to engage with a valiant “battle” with cancer than a death caused by medical mistakes, especially that of a child – the most unfaceable of fears. After Martha died, we received one card that said: “It is what we all dread – and it has happened to you.”

As absurd or insensitive as it seems, I even find myself envious of the circumstances of other children’s deaths. One father whose daughter died of an aggressive bone cancer told me he found comfort in learning that Spain’s football manager had lost his child to the same disease. “If he could do nothing, with all the money and fame at his disposal,” the father told me, “then there was nothing that could be done.” I have no such solace.

I understand the arguments for a “no-blame” or “just culture” NHS; this is not the place to rehearse them. More important is something that’s obvious but doesn’t get said enough: our trust in doctors should have limits. Medicine is like any other job: there are many talented workers in the NHS, but also those who are less dedicated and less able. Think of the old medics’ joke: “What do you call the guy who graduated last in his medical school class?” “Doctor.” There are plenty of clinicians prone to arrogance and complacency. Some doctors are “heroes”, but we should stop thinking of them all as such.

However indebted you feel to the NHS, don’t be afraid to challenge decisions if you have good reason to. It’s easy to feel cowed, but hold your ground. Remember most of the doctors in hospitals are just training. Don’t be afraid to ask how long a clinician has been qualified. Junior doctors are often green and trying to stay composed to impress their superiors. Make sure, if you can, that a single consultant has overall responsibility: we all know that if you’re answerable for something, you try harder.

Ignore the advice and look everything up on the internet. Google like crazy, educate yourself, ask questions and, if you are unsure, insist on a second opinion, or a third. Remember that it’s entirely possible you will be “managed” and “reassured” but not told the full truth. We certainly weren’t.

Be aware that much care in hospitals is less thorough at weekends. And understand the damage done by the hierarchical, patrician system – everyone defers to the most senior consultant. If things seem to be going wrong: shout the ward down. In our case, the cost of not doing so was too great. We had such trust; we feel such fools.

Now I live on the island. Instead of having Martha in the house, we go to visit her grave. Some of the inscriptions on the headstones nearby would have amused her: “Philosopher, Teacher, Nudist”, “International Man of Mystery”, “Forever Loved, Always Right”. But the people buried alongside her lived for seven or eight decades. Martha should have walked out of hospital like all the other children with her injury. Now Lottie has an empty bedroom next to hers, and a bench in the park with a plaque: “To my sister.”

I’d like to imagine a world in which Martha was transferred to intensive care in time and her life was saved. In this parallel universe, my daughter makes it to her 14th birthday. I talk endlessly about the doctors and nurses who helped her. I go on that fundraising walk. Bright and determined girl as she was, Martha aces all her exams and goes to a good university. I can just see her, laughing over a drink, getting stuck into student life, having a time of it. “I wonder what I’ll do for my GCSEs,” she wrote in her diary soon after starting secondary school: “It might affect my whole life.” In this fantasy, Martha has a career and the children I knew she one day wanted. She visits us at weekends and we recall those distant weeks when she was in hospital.

Oh, how I would love to live in that world.