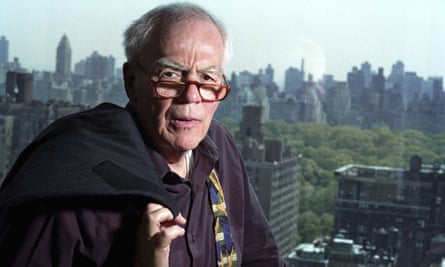

Jimmy Breslin, who has died aged 88, was a journalistic force of nature. “He was the greatest columnist of my era,” said the writer Tom Wolfe, “and practically all of it was reporting.” Breslin gave voice to the New York City street; as the champion of ordinary people, he reported their troubles and trials. He filled his columns with gangsters and thieves, whom he knew first-hand from drinking in the same bars. He told stories that smacked of blarney behind their anger. “Rage is the only quality which has kept me, or anybody I have ever studied, writing for newspapers,’ he said.

In 1999 Breslin heard of a Mexican worker drowned in cement when a building under construction in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, collapsed. “That’s my music they’re playing, I know this novel,” he said, referring to an obscure 1939 book, Christ in Concrete, by Pietro di Donato, about an Italian immigrant who died exactly the same way, and made his way to the scene. Breslin’s resulting book, The Short Sweet Dream of Eduardo Gutiérrez (2002), traced the dead man’s life back to Mexico and detailed the shoddy practices of the builder, who got away with paying a fine.

In that spirit, Breslin was the direct heir to Damon Runyon. Like Runyon he started as a sports reporter, and he followed Runyon’s dictum that, to find the better story, “go to the loser’s locker room”. He did that when President John F Kennedy was assassinated in 1963. Breslin’s story about Kennedy’s burial began with Clifton Pollard, the man who dug the grave, a working man of great dignity, who felt “honoured” to do his job that day. The story propelled Breslin to national prominence.

Breslin’s roots lay in the working-class neighbourhoods of New York City’s outer borough, Queens. His father, James, was an alcoholic musician who walked out on the family, leaving Jimmy’s mother, Frances, who also drank, to raise him and his sister, working as an administrator with the city welfare department. As a teenager, Jimmy was working part-time as a copy boy at the weekly Long Island Press. In 1950 he left Long Island University to join the paper full-time as a sports reporter, then moved into the city with the New York Journal-American.

His second book, Can’t Anybody Here Play This Game? (1963), a chronicle of the historically inept first season of the New York Mets baseball team, became a bestseller, and prompted his hiring as a columnist with the Herald Tribune. He was one of the early stars of New Journalism under the editor Clay Felker in the paper’s Sunday supplement, which became New York magazine after the paper folded in 1966.

He became enough of a celebrity to do commercials for Piels beer, and in 1969 he ran for president of the city council on the writer Norman Mailer’s mayoralty ticket, on a platform of turning the city into a separate state from the rest of New York. On election day, Breslin announced he was “mortified to have taken part in a process that required bars to be closed”.

In 1970 Breslin was beaten up by the mobster Paul Vario in a Lucchese family bar owned by Henry Hill, later of Goodfellas fame. One of his columns had offended another mobster, and he had also published The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight (1969), his first novel, based loosely on the Gallo brothers’ war within the Profaci family. The book was sold to Hollywood, for a 1971 film of the same name, and Breslin left his job at the New York Post. His second novel, World Without End, Amen (1973) was a sprawling Irish epic moving between Queens and Northern Ireland, whose style mixed the romantic with the hard-edged. He returned to a column in the Daily News and in 1977 he found himself at the centre of the city’s biggest story.

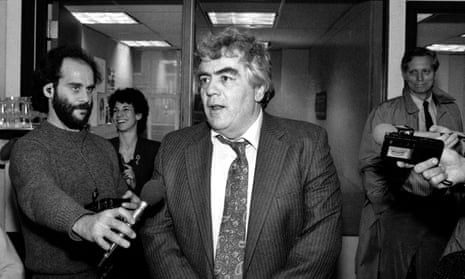

The serial killer David Berkowitz, calling himself Son of Sam, sent a letter to Breslin wishing the police luck in catching him. Breslin replied via his column, baiting him to write more. He and the News, in a circulation war with the Post, then recently bought by Rupert Murdoch and making the running on the story with the Aussie reporter Steve Dunleavy, were accused of sensationalising; Breslin said he was trying to help the police. He appeared as himself in Spike Lee’s 1999 film about the murders, Summer of Sam.

In 1982 he gave up heavy drinking after a memorable bender with Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan. In 1986 he was awarded a Pulitzer prize for commentary, for a column he wrote about the death from Aids of a young man called David Camacho.

Breslin wrote an excellent biography of Runyon (1991). I Want to Thank My Brain for Remembering Me (1997) was prompted by his experience of suffering a brain aneurysm. As his columns became less frequent, he produced more books, including a powerful indictment of the Catholic church’s sex scandals, The Church That Forgot Christ (2004), and the Runyonesque The Good Rat (2008). His novel I Don’t Want to Go to Jail (2001), about a gangster feigning dementia to avoid prison, seemed to inspire a similar storyline in The Sopranos. His final book was a biography of Branch Rickey (2010) who as general manager of the Dodgers took Jackie Robinson to Brooklyn and integrated major league baseball.

The greatest character Breslin created in his writing was himself. “I can barely handle legitimate people,” he once said. “They all proclaim immaculate honesty, but each day they commit the most serious of all felonies, being a bore.”

Breslin’s first wife, billed in his columns as “the former Rosemary Dattolico”, died in 1981 of cancer, and their two daughters also predeceased him. He is survived by his second wife, Ronnie Eldridge, whom he married in 1982, and by four sons of his first marriage, and three stepchildren.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion