The publicity for Britten's Billy Budd, opening tomorrow at English National Opera, shows a handsome young chap, bare-chested with a noose around his neck and something of a come-on air. Melville, I think, would be amazed to have it spelled out to him which part of the community was being appealed to in such a carefree manner. He was a daring writer, yes, but he would not have thought of himself as daring in that particular direction.

His novella, Billy Budd (Sailor), An Inside Narrative, unfinished at his death and not published until 1924, is often seen today as a classic study in homoerotic sadism, along with Robert Musil's Young Törless and DH Lawrence's The Prussian Officer. But this is only one possible reading of the text. It is not, I think, its consciously encoded message.

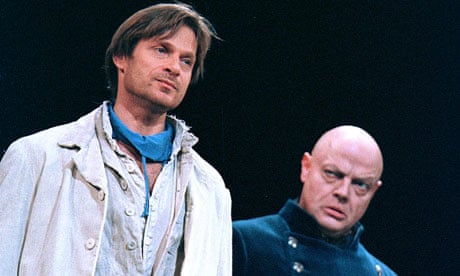

Melville's story tells of a sailor, Billy Budd, who is surreptitiously persecuted by the ship's master-at-arms, Claggart. He refuses to be trapped into joining a mutiny, but is accused of doing so by Claggart in front of Captain Vere. Billy is seen as the embodiment of innocent goodness, his only flaw being a stutter, which makes it impossible for him to express himself in moments of agitation. In his outrage at the false accusation, Billy strikes Claggart dead, and has to pay for this act with his life.

Very soon after the story's publication, it was read by EM Forster, who in his Commonplace Book of 1926 diagnosed Melville as a suppressed homosexual. Still, Forster was considering the depiction of goodness and evil in fiction, and this is what Melville, too, thought he was talking about in Billy Budd.

It is striking how often critics will casually assert as fact what turns out on inspection to be a quite fanciful reading. They make Melville sound much steamier than he is. A chapter in his Redburn (1849) is said to describe a visit to a male brothel in London. This would be amazing if true of a novel published in a conventional way at the time. The place in question turns out to be a luxurious gambling den. Another part of the same book is described as an extended masturbation fantasy: a street-organ player says he likes playing with his organ ... and off we go.

Everyone is entitled to their own pleasures of the text. I prefer, however, not to be disappointed by the critics or to feel so roundly deceived. Melville's chapter on whale semen in Moby-Dick is amazing, and Lawrence, who writes so thrillingly about the 19th-century novelist, was within his rights in calling the next section, The Cassock, "surely the oldest piece of phallicism in all the world's literature". But it should not be allowed to stand as conventional wisdom that, when Billy Budd spills his soup on the deck just as his would-be persecutor Claggart is passing, this is heavily (even tiresomely) symbolic of a sexual emission.

Words like "rigid", "erect" or "ejaculate", in the prose of this period, should not be press-ganged into inappropriate service. After Billy is hanged, the surgeon and the purser have a discussion about the unusual absence of "spasmodic movement" or "muscular spasm" in the corpse. They are talking about the body not jerking. They are not talking about sexual climax. It is the critics who are jerking off.

The figure of the Handsome Sailor, as represented by Billy, is one in which beauty and goodness are the same thing. Billy, Forster says, "has goodness, of the glowing, aggressive sort which cannot exist unless it has evil to consume".

Claggart, the ship's master-at-arms, is both attracted to him and repelled: he must find a way to destroy the existence that stands as a rebuke to his own. And Melville is good on the way an officer, on board ship, can persecute one of the men. Here he is in White-Jacket, talking about just that: "If a captain have a grudge against a lieutenant, or a lieutenant against a midshipman, how easy to torture him by official treatment, which shall not lay open the superior officer to legal rebuke. And if a midshipman bears a grudge against a sailor, how easy for him, by cunning practices, born of a boyish spite, to have him degraded at the gangway. Through all the endless ramifications of rank and station, in most men-of-war there runs a sinister vein of bitterness."

Because this sort of surreptitious persecution and its counterpart, favouritism, are familiar to us from childhood as among the injustices that affect us most deeply, there is a power in the story of Billy Budd that grips us by analogy with our own experience. We want to know what motivates Claggart to persecute Billy.

Forster didn't believe evil existed, but he recognised that certain writers such as Dostoyevsky and Melville disagreed. To Melville the key to Claggart was what he called "natural depravity", a kind of innate evil which is "without vices or small sins. There is a phenomenal pride in it that excludes them from anything - never mercenary or avaricious. In short, the character here meant partakes of nothing of the sordid or sensual. It is serious ..."

Elsewhere Melville tells us that "Claggart could easily have loved Billy but for fate and ban", which I take to mean that his depraved nature, his innate disposition to envy what is good in another, made it impossible, as also did the taboo against same-sex love.

To Melville, what was "sordid" was thereby ruled out. To Forster, this was by no means the case, nor was it so in the homosexual literary circles of his day, where there seems to have been an eagerness to identify sadistic persecution of young men or boys with suppressed or frustrated homosexuality. That is why Christopher Isherwood, asked by Britten to adapt the story of Peter Grimes for a libretto, refused to do so. He thought Crabbe's tale anti-homosexual.

A quarter of a century after he first read Melville's tale, which he brought to the attention of the British public in Aspects of the Novel, Forster was asked by Britten to collaborate with Eric Crozier on the libretto of Billy Budd. He not only agreed, he took his role seriously to a degree that worried Britten, who came to prefer a more passive kind of librettist.

The key decision, made early on, was that Peter Pears would sing the role of Captain Vere, and the part was written for him. This character had always been important in the story, but now his nature and his motivations were pivotal. Billy is persecuted clandestinely by Claggart, who accuses him of mutiny in front of Captain Vere. Outraged, Billy impulsively strikes Claggart. "Struck dead by the angel of God!" exclaims Vere. "Yet the angel must hang!"

In Melville's story, Vere then acts in a way the ship's surgeon thinks mad. He conceals the body of Claggart, calls an immediate "drumhead court" and sets in motion the process that ends in Billy's hanging. This goes against "usage". As the ship's surgeon states, Vere could have arrested Billy, waited until his ship rejoined the navy and then referred the extraordinary case to the admiral.

In Forster's libretto, we do not realise this option was open to Vere, or that he is a weak leader acting hastily in fear of mutiny. Instead, the court and Vere take the only decision they can, and then comes what for Vere is a kind of miracle: Billy forgives him in advance, and in the moment of his death he calls down a blessing on him, which the crew repeat. Mutiny is averted.

In the last moment of the opera, Vere admits he could have saved Billy, that Billy knew it, and that his shipmates knew it. But Billy, by blessing Vere, has "saved" him, and "the love that passes understanding" has come to him. It is a glib and weak conclusion and, if it does not convince, the best thing to do at this point is to ignore the text and listen to the music.

But if, at the end of the applause and when the music has begun to recede, the question still remains as to why Vere lets Billy die, I would suggest, as Humphrey Carpenter does in his biography of Britten, that Forster, not the composer, is at the heart of it. In Melville's story, Vere dies in action soon after Billy's death, with Billy's name on his lips. And the name is spoken not "in the accents of remorse". There is a mystery here, and we do not know that Melville would have resolved it, had he ever really finished the story.

· Billy Budd is in rep at English National Opera, London WC2, from tomorrow until December 17. Box office: 0870 145 0200