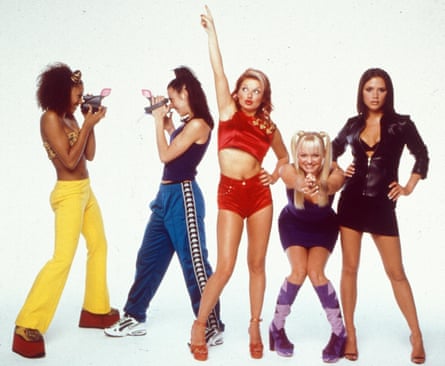

It’s often said that meeting a Spice Girl feels a lot like encountering a cartoon character. You can see it with unfiltered Mel B, poised Victoria and Emma, still resolutely family-friendly at 43. Geri’s modern lady-of-the-manor act is the antithesis of her old outrageousness, yet she is still swimming in camp. But with Mel C – or Melanie C as she styles herself these days – that’s not the case.

Even if she was your favourite Spice Girl, and you have never met one before, and she turns up to your interview in a closed Kings Cross bar wearing a hoodie and trackies – just as she would have done when Melanie Chisholm became Sporty Spice 25 years ago – it’s still only the little things that nod to the fact she was in one of the biggest girl groups of all time. She speaks quietly, often in an awed whisper, and is not beholden to the propaganda-like version of the Spice Girls’ story that some of her bandmates uphold.

Yet her instantly identifiable scouse accent is unchanged, and she repeatedly recalls memories with an “it’s funny …”, as you might if you had had to figure out how to make sense of becoming farcically famous at the age of 22. The hardest part of that, Chisholm says, was the dissonance between the shy girl she was and the gobby media caricature: “Am I this person I’ve always felt like I am?” she wondered. “Who should I be? Should I be more like they’re saying I am; is that who they want me to be? Is that who I want to be?”

At 45, it has taken her a long time to reconcile her anxieties about her identity. She has always sung about her issues with self-acceptance, from her 1999 solo debut, Northern Star, to the new music she is releasing next year. On the demos I hear, she sings about having nothing left to hide and refusing to change for anyone else’s expectations, celebrating differences and working towards self-love. She wrote them with left-field pop artists such as Shura, Rae Morris and Little Boots, producing disco-tinged synth-pop that recalls classic Robyn and the carefree joy of Carly Rae Jepsen. It is her best work since she went it alone 20 years ago.

So far, she has released one single, High Heels, written for the queer drag collective Sink the Pink. They have been working closely together this year, touring international Pride celebrations (including one in Jair Bolsonaro’s Brazil), where Chisholm has been singing backed by a troupe of queens dressed as the Spice Girls. They have helped her nix her self-doubt, she says.

“The drag queens are larger than life and I’m actually quite quiet,” she says. “Sometimes I feel I’m not enough, I’m not outspoken enough, I’m not funny enough, I’m not good enough.” She becomes gently indignant. “And I thought: ‘You know what? That’s bullshit. I am enough. I’m doing this incredible thing and I’ve had this incredible career: it’s time to really accept every little bit of me, even the shit bits.’”

Bland self-acceptance is the lingua franca of the modern pop star. But it is poignant to hear Chisholm – who really is outspoken and funny, with a weapons-grade laugh – talk about getting there after having watched her struggle for two decades. She was always the shy Spice Girl, in a group dominated by massive personalities. On her 2016 album Version of Me, she sang about being bullied by one of the others and spoke of letting someone “shit on” her. I tell her I assumed it was Mel B, and she nods. Chisholm grew up in a “really quiet household”, never fighting with her mum, so she hated confrontation (although she did start weightlifting after a girl tried to beat her up).

She almost got booted out of the band once: in February 1996, five months before they launched, they were invited to the Brit awards. “I got a bit lairy and I told Victoria to fuck off,” she recalls with a guilty laugh. “I upset her, and I was told that if that behaviour ever happened again, then” – she makes a guillotine gesture. Generally, though, she learned “that to have an easy life was to stay quiet”. Staying out of the line of fire came naturally, even though it came at a cost to her mental health: Chisholm calls herself a people-pleaser who can always see the other side of an argument. “I’m always the diplomat.”

Once the band took off – the debut single, Wannabe, spent seven weeks as UK No 1 – their schedule was so intense that Chisholm says she sometimes sees photos of the band and can’t remember where they were taken. “We had our crazy few years and we didn’t think about the future,” she says. “It wasn’t on the radar – which is a shame, really, because if you did, you’d maybe appreciate the moment a bit more.”

She says they were well cared for. The problem was, she didn’t want to be looked after. “I was a grownup, thank you very much,” she says. Instead, she entered “survival mode”, spending three hours a day in the gym, subsisting on fruit and steamed vegetables. “My life was out of control and the only thing I could control was how much I ate and how much I exercised,” she says. “One of my biggest regrets is that there were years when I wouldn’t socialise because I didn’t want to eat in front of people. I just think: ‘Cor, what a waste of life.’”

The Spice Girls’ ubiquity obscures the fact that they only existed as the original five-piece for 22 months, with Geri quitting in May 1998. The other four slogged on through two more tours. Chisholm says it couldn’t have lasted much longer. “We destroyed ourselves,” she says. “We were exhausted, we were homesick.” They never formally split – which, I tell her, was torture for a 10-year-old with a blind faith that they would return. She laughs, apologetically. They never announced the end, because they couldn’t be bothered with the press interest. “We were burying our heads in the sand. And, to be a bit of a wanker, you’re always a Spice Girl; it never stops.”

She did try to stop for a bit. When she went solo, Chisholm bleached and cropped her hair. “I was angry,” she growls, comically. She wanted to be seen as an individual, to escape the band’s legacy. She was shocked by the snobbery when she played the V festival solo and got pelted with apples, urine and, she thinks, Weetabix. “I was a bit naive,” she says. “But it was a baptism of fire. I’m really grateful that I did it, because if you can survive that, you can survive anything.”

This was when she started having depression, initially thinking it a symptom of her fame. “I was a Spice Girl,” she says with horrified awe. “For five minutes, I was one of the most famous people in the world – how do you deal with that? Everyone treats you differently.” She assumed it would pass. “And I’ll just be the happy-go-lucky, normal person I was when I was 19,” she sing-songs. “And then, unfortunately, some feelings of depression have come back over the years and I’ve realised, this is part of who I am.”

She sought professional help. She still sees a therapist every week and has established a healthier relationship with exercise: a triathlon fiend, she wanted to try out for Team GB, and she is in a pre-Christmas pull-up competition: she can do five, but wants to get to 10. She rubbishes the idea that women who love exercise must be unhappy with their bodies. “I love trying to better myself, trying to be faster, stronger, hold a note for longer,” she rhapsodises. Having her daughter, 10 years ago, helped, too. (The father was property developer Thomas Starr; they split in 2012.) “It made me realise the things I would sometimes allow to happen to me, I would not have happen to her. I often feel like she’s my teacher. She’s given me a lot more courage to treat myself better.”

Nevertheless, at the end of 2018, with the Spice Girls reunion tour looming, Chisholm was feeling anxious about returning to their complicated dynamic. Her worries were dispelled “100%”, she says. “It was like a fairytale. We wanted to do the Spice Girls show to end all Spice Girls shows: nostalgic but modern, a celebration, bringing everybody together.” She cackles. “We also wanted to give everyone a really fun night out because we’re all so fucking over Brexit.”

The reunion was a product of a “rare moment when we all agreed” – Chisholm had refused a mooted reunion for Wannabe’s 20th anniversary in 2016. Mel B has been the most persistent about rebooting the band, adding to the sense that it plays a bigger role in some of their lives than others. Last year, Brown’s memoir detailed her experience of an abusive marriage, and explained how work offered a refuge. Her ex-husband denied any physical abuse.

Did reuniting ever feel like a responsibility to a friend? “What happened to Melanie was so horrific,” Chisholm says. “There were quite a few tears shed over the time we spent together because we hadn’t been together day after day for a long time. To rekindle those friendships and remember the things we love about each other, it was hard.”

She stares across the empty bar and brings up Brown’s marriage. “I feel – and she knows this – I feel shit that I wasn’t more determined to intervene,” she says. “But what can you do? We’re all grownups. I couldn’t wade in there and say: ‘I think your husband’s a prick, I want to take you away.’ Melanie and I did fall out about it. And I didn’t handle it very well. It was difficult and she couldn’t leave that situation until she was ready. Thank God nothing happened to her. You do feel shit that you didn’t do more.”

While she says – contrary to comments from Mel B and Emma – there won’t be new music, Chisholm would love to do more shows, playing territories the band never visited. “I’d do it at the drop of a hat,” she says. I tell her that the Guardian rarely reports on rumoured reunions, but that we often make an exception for the Spice Girls owing to the mania around their existence. Why are we still so obsessed by them? She laughs. “It was quite unusual for a female band to be that successful – and not only successful musically; it was a very cultural movement.” Plus, we are living in a period of nostalgia for 90s Britain. “British music was ruling the world. Even politically, things were on the up. Or we thought so.” And the Spice Girls, she says, are like an ongoing soap opera.

The response to this year’s tour – and admiration from a generation of young artists including Billie Eilish – renewed Chisholm’s solo ambitions. Her previous albums flew under the radar, but the partnership with Sink the Pink and the hiring of a snazzy new PR company suggest someone who wants to make a bit of a splash again. She agrees. When her manager of 18 years retired, Chisholm realised she wanted to speed up. She hired a new team, who gave her a “kick up the bum”, and sought out exciting young writers and producers, which she says has produced a high strike rate of good material.

She knows she is a “mature” pop artist, and tempers her expectations accordingly, relishing the opportunity to play stadiums with the band and dedicated audiences on her own. “Even Spice Girls shows in the 90s, I’ve never experienced the reactions we got this summer,” she says. “I’m not a fan of arenas – good job, innit?!” She unleashes a filthy laugh. “But I love clubs. How lucky that I can do that.”

I hope people give her great new music a chance, especially since Chisholm’s work feels so in sync with 2019. She has been talking about her mental health for nearly 20 years, and her work with Sink the Pink feels like genuine advocacy. She marvels at the “privilege” of spending time in queer and non-binary communities, and is a vocal transgender ally. “I mean, Jesus Christ, can you imagine growing up feeling like you’re in the wrong body?” she says. She’s shocked by the prevalence of transphobia in British culture and sport. “We have to move on,” she says firmly. “Things change. Thank goodness people are able to be who they truly feel they are rather than living miserable lives or secret lives. It’s something that has to be acknowledged and addressed.”

She knows what it’s like to make up lost ground. “I had a hard time in my early 30s. Sometimes I think, did I miss my opportunity of being in my prime? Was it wasted?” Being in her 40s “feels like a new opportunity for me to really go for it again, and just enjoy it,” she says. And off she goes to get the tube, resolutely human.

Melanie C’s single High Heels is out now on Red Girl