Spike Milligan, protector of catfish against American artists, may care to know that for the past 22 years an American psychologist, Dr Peter Witt, has been systematically deranging spiders.

In a laboratory where temperature and light were regulated day and night, he dosed them with mescalin, caffeine, carbon monoxide, amphetamines, and apparently most of the other drugs or substances which have been found to have an ill effect on humans.

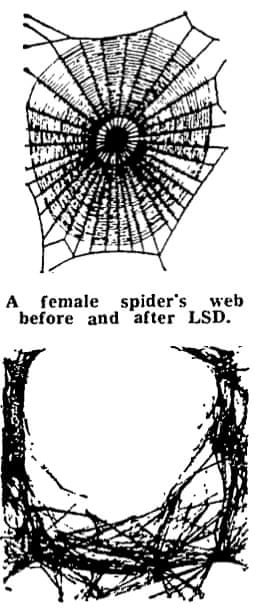

The results of this indefatigable work have been at once predictably horrifying and scientifically inconclusive. His stoned spiders, normally among the most delicate and admired artificers of the natural world, have spun webs which are both ugly and inefficient at catching flies.

Dr Witt keeps them in individual aluminium frames where their webs can be easily photographed for analysis. As the English magazine. “Drugs and Society,” notes in a study of his work, their daily spinning is usually a remarkably precise and complex process whose mechanisms we do not fully understand.

Every morning just before dawn, the spider makes the web in 20-30 minutes by laying down radii at set intervals and then crossing the radii in pendulum and round turns to lay the insect-catching zones. Then it settles down at the hub with its eight legs spread on he radii to pick up the vibrations from a captive.

Drugs radically interfere with this behaviour. Tranquillisers which were among the mildest drugs administered, often made them spineless. The webs were smaller and lighter, with less thread and fewer turns and radii. These would have been less good at catching flies. Under relatively high stimulating doses of amphetamines the spiders tried to build webs at their normal frequency but the result was “highly irregular and unstructured.” The webs lost their orbital shape, looked random in construction, and were “ineffective” as traps.

With lower amphetamine doses, webs kept their geometry, but radii and turns were irregularly spaced.

Very high LSD doses “completely disrupted” web building. Some spiders stopped spinning altogether. High but less “incapacitating” doses produced very complex three-dimensional webs which often appeared “strikingly psychedelic” and presumably less efficient at registering vibrations.

Still lower LSD doses tended to produce webs which were compulsively regular, with accurate and consistent spacing between threads.

At the end of this programme of mental ruin, Dr Witt is still uncertain how far his results apply to human beings. One problem must be that we are still unsure precisely how a drug like LSD operates chemically on the human brain, let alone the spider mind.

An exact analogy between the two organisms seems to be at present beyond the grasp of research. Dr Witt has proved that drugs disrupt an activity essential to life in spiders. But it could be argued that we already knew as much from similar experiments with rats.

Spiders, of course, come higher in the hierarchy of human sentiment than rats, or catfish. A member of the British Arachnological Society expressed shock when told of the experiments.

However, scientific interest in spiders appears to be at a low ebb here (the Zoological Society library lists only two research projects), so there is little likelihood of local provocation to the Milligans among British spider lovers.

If it is true, as the baffled catfish-electrocutor implied, that the United States has recently become more innured to public death than Britain, it is also true that she has had a much more worrying experience of drugs. In a context of 315,000 heroin addicts, the tolerance limits for experiments seeking “fundamental answers to the mysteries of drug effects” are bound to be extended.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion