On radio phone-ins at the moment, one particular word resonates. Government decisions, ministers and U-turns are regularly described as "farcical". This f-word is partly a surrogate for the other one they can't say on air, but it also sums up a common attitude to current events: that our politicians have lost control as catastrophically as a theatrical character caught semi-naked with his mistress when the vicar rings the doorbell.

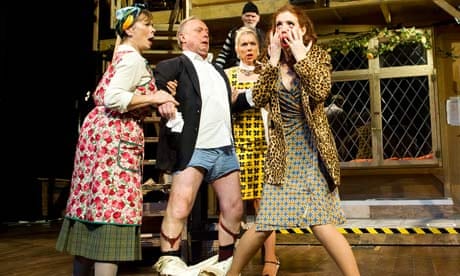

This atmosphere of absurdity in public life may be one reason why British theatre is currently so fascinated by farce. The National theatre's One Man, Two Guvnors – adapted by Richard Bean from Carlo Goldoni's 18th-century comedy Servant of Two Masters – has been a huge hit; and, with a new cast taking over in London when the first transferred triumphantly to Broadway, is now flanked in the West End by revivals of Michael Frayn's Noises Off and Joe Orton's What the Butler Saw, classic farces from 1982 and 1969 respectively.

And last week, the Donmar in London opened a version of the 1962 play The Physicists by the Swiss-German absurdist Friedrich Dürrenmatt, which strikingly echoes What the Butler Saw. In both, a police investigation takes place in a mental hospital, which contains a psychiatrist who may be more deranged than the patients – perfect examples of the reversals of logic and expectation on which farce depends.

Although primarily a theatrical form, farce is also prominent elsewhere at the moment. One of the summer's bestselling novels is Skios by Michael Frayn, who, having conquered the genre theatrically with Noises Off, experiments with making physical comedy work on the page: a chancer on holiday in Greece pretends to be a distinguished lecturer whose name is written on a card held by a taxi-driver at the airport, resulting in multiple misunderstandings and embarrassments. And, with audiences of over 8 million, the most popular TV comedy at the moment is Mrs Brown's Boys, a piece that first achieved popularity in Ireland as a series of stage farces involving disguise, slapstick and mix-up.

So why, in these recessionary times, does farce seem to be the smart way of making money? The tempting explanation is that, in an economically and politically painful period, it distracts us from serious matters, being the form of entertainment most likely to achieve the cathartic release of laughter. Support for this theory may come from the fact that farce was hugely popular around the time of the Great Depression in the 1930s. These so-called Aldwych farces, named for the London theatre where they were performed, were hit plays by Ben Travers, who died in 1990; among them was Rookery Nook, about a woman in pink pyjamas who has been thrown out of her home by her Prussian stepfather. Travers had been strongly influenced by farces written in France by Georges Feydeau during another period of social, political and economic tension: the turn of the 20th century and the approach of the first world war. Feydeau's plays, including 1907's A Flea in Her Ear, helped establish the shorthand image of stage farce: an adulterer who bumps into his wife and employer during a dirty weekend in a hotel.

If farces are regarded as providing a good time in bad times, it's because, as John Caird argues in his illuminating book Theatre Craft, the genre will inevitably be funny if done properly: "A good farce obliges the audience to believe both in the characters and the events to the point where laughter is their only recourse."

Josie Rourke is the director of The Physicists, a work that she says "starts off as a farce but ends up as a tragedy". She agrees the form has an appealing clarity: "Farce is a reassuring form for both audiences and directors. You're dealing with absolutes: either that door will open on cue or it won't. It's actually quite a relief not to be standing around in rehearsals for 30 minutes, discussing why something happens. I think it's also a satisfying form for audiences, in that you are rewarded for listening and understanding. There's a particular laugh of satisfaction when something set up early on pays off later."

Caird suggests that directing a successful farce depends on removing any variables: "You must spend hour upon hour […] honing the physical and linguistic routines and rhythms that will eventually release the audience's laughter. Nothing in farce can be left to chance." But, however hard the work done in rehearsal, chance will always be part of live performance; and because the action of farce often involves rushing through doors and descending staircases with trousers at sock level, actors are at genuine physical risk. Tom Hollander broke his elbow during the 2010 Old Vic revival of A Flea in Her Ear, while Michael Frayn has apologetically acknowledged that, on several occasions, ambulances were called to Noises Off after falls went wrong.

Sean Foley, who is directing the current What the Butler Saw, last year staged a modern French farce, The Painkiller, in Belfast. The title became rather ironic: several actors ended up performing with bruises or bandages, or were replaced by understudies, after accidents during the physical business that pervades Francis Veber's play, in which adjoining hotel rooms are booked by an assassin and a would-be suicide. These parts were played respectively by Kenneth Branagh and Rob Brydon, who are expected to bring the production to London if their diaries can be aligned (although they may ask for a bigger first aid kit).

"I think that real sense of danger is part of what the audience enjoys," says Foley. "In a way, farce is the most purely theatrical form. There's a visceral, palpable sense that this thing is happening live in front of you. And when the wardrobe falls on someone's head or someone stubs their toe – and maybe they really are stubbing their toe, night after night – it's exciting for an audience. That's why it feels so live and dangerous."

The risk comes largely from the extreme pace farce demands. Foley stresses this need for speed: "A phrase I end up using a lot in rehearsal is, 'I need to see you acting, I don't need to see you thinking.' People are confronted with a situation and they react – 'Oh my God, there's a policeman coming through the door.' Technically, farce is about taking away all the thinking time, not only from the characters but also from the audience. We never drop into a zone where things are being considered – they are just happening."

While farce can cut and bruise actors, I suspect it can also touch audiences more painfully than its stereotype of silly entertainment suggests. Watching the revival of Noises Off, it struck me that the theory that door-slamming, trouser-dropping comedy thrives in gloomy times because it provides easy laughs is only partly accurate. Parts of Lindsay Posner's production felt genuinely disturbing, because the characters – a theatre company touring a bedroom farce round the UK – seem so desperate to keep going, even as their professional and personal circumstances unravel. Is farce, perhaps, not just a distraction from unhappy times, but also a reflection of how it feels to be caught up in them? Rourke thinks so. "When farce is brilliantly done," she says, "what happens is pretty radical. You do get a sense of almost existential desperation. Is this really happening? Am I really here?"

And, although farce is sometimes viewed as inherently silly and flimsy, the plot of The Painkiller turns on homicide and suicide. Similarly, Foley found darkness possible in physical comedy: "My view of What the Butler Saw is that it's a deeply shocking and subversive play, masquerading as a farce. In a lot of farce, taboos are tackled. People have argued that the best subjects for comedy are death and sex. And in farce, you always have sex and you very often have death, which really gets people laughing. Farce does deal, though some would say in a very light way, with very deep themes."

Quentin Letts, theatre critic of the Daily Mail, confessed in his review of One Man, Two Guvnors that he feared he might stop breathing because he was laughing so much. It's this sense of helplessness – that laughter is controlling us rather than the other way around – that is the special pleasure of farce, the fear that it may not only be prat-falling actors who need attention from paramedics. "Our intention has always been to try to get people to that state," says Foley. "It's a sort of laughter that can't be achieved through any other art form."

When people accuse the government of being "farcical", they mean they are not doing their jobs properly; but on stage, says Foley, chaos and misunderstanding can only result from professional perfection. "The wonderful paradox of farce," he says, "is that there's a double image going on on stage. At the same time as we are laughing at the incompetence of the characters, we are aware of the deep expertise of the performers. And that is a very theatrical vibe."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion