They began assembling shortly after midday, union jacks fluttering above their heads. By 2pm on 13 August 1977, 40 years ago, hundreds of rightwing extremists were ready to march through Lewisham in south-east London.

Above them, on New Cross Road, vast crowds of counter-protesters had massed to prevent the 500 supporters of the National Front from marching.

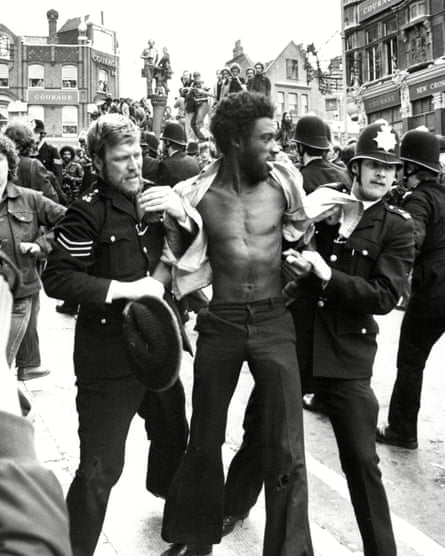

Ferocious clashes would follow, first between anti-racist demonstrators and the NF and, later, between police and counter-demonstrators as police briefly lost control of the centre of Lewisham. In the hours of chaotic fighting, at least 111 people were injured, including 56 police officers, and 214 people arrested. The violence would prove seminal; calibrating the tone for race relations in the capital, paving the way for increasingly combative police tactics and initiating the decline of the far right, a trajectory it has yet to amend. The police used riot shields for the first time outside Northern Ireland, and baton charges and mounted police were used in an attempt to disperse the crowds.

That Saturday 40 years ago marks the most recent highwater mark of white nationalism and fascism in the UK. Crudely stoking concerns over immigration while offering even cruder solutions – stopping non-white immigration and supporting repatriation – the NF were nonetheless becoming a bona fide force.

The most widely accepted narrative of the violence suggests that the NF chose to march through Lewisham, with its sizeable black community, to provoke a strong reaction.

Yet another factor was also in play, one that has been largely forgotten since: the NF had targeted Lewisham because they knew they would be welcomed by many residents.

“The dialogue which gets overlooked, because it is less palatable, is that there was considerable support for the NF,” said John Price, head of history at Goldsmiths University, which stands metres from where the day’s opening clashes took place.

Less than a year before the so-called battle of Lewisham, a local council byelection in Deptford saw the far right secure almost half the vote. Together the National Front and its breakaway faction, the National party, secured 44.5%, a total not quite enough to beat Labour but sufficient to relegate the Conservatives into fourth place.

Among other things, the vote was electoral affirmation that the Tories were being punished for their “moderate” stance on immigration. According to Paul Jackson, an expert on far-right extremism and a historian from the University of Northampton, a hotchpotch of white supremacists, neo-Nazis and classical fascists were winning the populist debate on immigration. Before the New Cross march, the NF had as many as 14,000 paid members. Jackson said: “People who would ordinarily be drawn to the Conservative party were seeing the National Front as radical, a movement that might answer their fears about immigration.”

But the battle of Lewisham would turn into a disaster for the far right. Although its boot boy element would glorify the violence as a great day out, the NF’s ambition to become a political force began to ebb away even as the broken bottles were being swept from Lewisham’s streets.

For a start, the NF had found themselves vastly outnumbered on a patch they thought was their own – at least 4,000 counter-protesters had turned up. Second,the NF were also stopped from marching as they had intended. They were separated from the counter-demonstrators and then marched through empty side-streets by hundreds of police before being led on to waiting trains – the first time that had happened to the NF, a development that challenged its self-identity as a potent street movement.

In a similar way that the 1936 battle of Cable Street, four miles north of New Cross Road, had dealt a definitive blow to the aspirations of Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists, the battle of Lewisham helped frame the NF as unpopular, thuggish and simultaneously feeble.

White and black youths, and local anti-racist groups among others forced the NF to abandon its march in a similar manner to how the ranks of Mosley’s group were turned away by London Jews and Irish labourers. Despite their capacity to generate significant support as well as fear, the two London defeats, 40 years apart, helped ensure that the message of the two extremist movements would never be translated into political potency.

“The official literature of the NF talks a lot about how Lewisham was very damaging to them. They turned up with what they thought was a force but were hugely outnumbered, then they were prevented from marching through Lewisham – plus press coverage did not paint them as victims but painted them as guilty as anybody else. They never really maintained their hold on the area,” said Price.

And a change of direction within the Tory party would deliver another crushing blow. Margaret Thatcher, as leader of the Conservatives, had spotted the political capital to be seized from adopting a tough stance on immigration, and was determined to shift the party away from the position of her more moderate predecessor, Edward Heath, which had prompted some Tories to support the NF. Her standing in the polls soared after a television interview five months after Lewisham during which Thatcher warned that Britons were afraid they “might be rather swamped by people with a different culture”.

Jackson said: “Before the 1979 general election the National Front still hoped to break through but Thatcher was more sympathetic to people’s concerns over immigration and that took away a lot of their momentum. The political space around the NF changed and led to its collapse.”

The battle itself has since become mythologised. Testimony from witnesses has often varied, frequently contradicting official reports and leaving historians struggling to offer a defining narrative. The emergence last week of long-lost footage, thought to have been destroyed, has already offered a fresh understanding of the protest. Specifically, the reel sheds light on uncompromising policing tactics. Images show officers lined up with riot gear for the first time on the UK mainland, a development in public order policing which many have argued precipitated a move towards a more no-nonsense approach.

It also reveals the extent to which police horses were used along with the vast number of officers deployed – 2,500 were summoned into action that day.

Professor Tony Dowmunt of Goldsmiths’ media and communications department, who helped track down the footage, says that the large deployment of police horses could be considered part of a shift in tactics that would lead to Orgreave, the pivotal confrontation between police and picketing coal miners at the South Yorkshire coking plant in 1984, where officers were filmed charging horses at miners.

“It shows a very heavy use of police horses, it’s reminiscent of Orgreave in a way. There are also shots of police behaving pretty brutally towards demonstrators,” said Dowmunt, who was present at the protests four decades ago, an experience he recalls as “very startling and scary”.

Dowmunt, who said that the footage was discovered four weeks ago following a 10-year search that began shortly before the battle of Lewisham’s 30th anniversary, believes it may also help shed light on allegations of police brutality.

Those came accompanied by claims of racism among the Metropolitan police. The battle itself was preceded by the arrests of 21 young black men on what many felt were spurious reasons. “People were concerned that there was something not quite right about how police were going about their job. The Met have admitted there were issues of racism during that time,” said Price.

But what about racism in Lewisham now? Standing beside the New Cross Inn, close to where the first disturbances began 40 years ago, Curtis Essel, 23, who runs a website celebrating London’s multiculturalism, said he felt the Met was becoming less discriminatory: “When I was 14 or 15 I was getting stopped and searched all the time, but the police seem to be doing it less so now.”

Nearby, close to where the NF once gathered and where a shop selling vegan food and vinyl now stands, 85-year-old Doreen, who came to New Cross from Jamaica 50 years ago, said she had learnt to tolerate bigotry: “I learnt to just get on with it. In that sense the area has improved but there always was a sense of community here.”

Today that community will come together once again when a maroon plaque is unveiled at 323 New Cross Road, where the demonstrations began, and where Lewisham fought back against the fascists.