After hurricane Sandy hit, Congress granted federal agencies a total of $48b for disaster recovery. Two years later, much of it still hasn’t been spent.

Surprising, right? It’s true: the Office of Housing and Urban Development (Hud) has received $15bn for community infrastructure, and has only spent 12%. Transportation has spent about the same of its $12bn allocation for things like subway upgrades. The Army Corps of Engineers got $5.4bn for coastline protection, and hasn’t even spent a billion. Even Homeland Security, which received more than $11bn for Fema’s immediate emergency response, still has almost half to spend.

So what is a realistic timeframe for spending federal money?

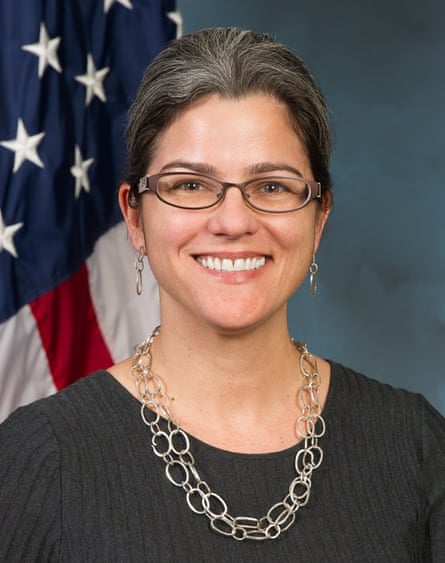

This timeline was actually expected by Holly Leicht, Hud’s regional administrator for New York & New Jersey. In fact, the pace at which Hud is spending is almost on schedule. However, she says, it is the government’s fault for not making that schedule clear earlier to residents and the media. While many public offices I reached out to for this series were wary of my interview requests, her office actually contacted me – perhaps to proactively correct this narrative.

“Hud is a mystery to too many,” she told me. “It’s important for people to understand the big picture of how this all works.”

In our interview, Leicht carefully details how federal money flows, why it takes so long, and where she sees political incentive for longterm spending on storm-proofing.

First, for those who know the acronym but not the nuts and bots, what exactly does Hud do?

So Hud’s major role is as a funding agency. We’re mostly associated with affordable housing, but we have a number of grant programs that fund all kinds of economic development, urban planning, and housing projects. The money goes directly to grantees to spend, which are usually states and counties – New York City is one of the few cities that has a big enough population to be a direct grantee. So in the case of NYC, all the money goes through them. We aren’t writing any check to homeowners or anything. The funding goes to the Office of Management and Budget, and they allocate it to various agencies to implement programs.

But the money you’re spending on Sandy recovery and natural disaster resilience is separate from your usual programs, right?

Right. Congress appropriated disaster recovery to us after hurricane Sandy. In my head, this is the chronology of money post-storm:

Fema’s money is the first in after a natural disaster – they have a standing authority to come in and quickly fund things as needed.

Next is our Hud money and the FTA money, along with some other departments ... that’s the medium money that’s going out now and starting to do these midterm projects. Ours isn’t really “emergency money” the way Fema’s is, because we don’t have that standing authority. After Sandy, we had to wait for the appropriation from Congress, which came months after the storm.

And then there’s the Army Corps. So the Army Corps got quite a bit of Sandy recovery money, but they have a way longer term vision.

Wow, thanks! I’ve been looking for such a straightforward explanation. So, I noticed that you were allocated the most recovery money out of every agency. What happened after you received it?

So after we got appropriated the $15bn to spend overall, we had allocate a portion to New York City based on their level of need. Then the city put together an action plan, which basically says, “Here are the things we’ll spend the money on.” And it’s pretty general. They’d say: “We’ll create a housing program! We’ll create a small business recovery program! We’ll do infrastructure work!” We go back and forth, but ultimately approve it.

But we allocate it in smaller amounts within that, and they have to come back when they’re ready for those amounts. Congress put very specific spending deadlines on that money – so the city doesn’t want it all at once, because once they have it, that clock starts. They need to be ready to spend it.

At this point, we know what all the Sandy money will get spent on and who’s getting what. Now it’s a process of them finishing the planning and actually requesting the money to start building.

Is that why so much of Hud’s money still hasn’t been spent?

Exactly. This is one of the things that’s actually not well explained in the process. I’m totally sensitive to all the people who are angry and frustrated with the fact that it’s two years after the storm and they’re still not in their homes. And it’s up to us, the government and elected officials, to do a better job explaining our realistic expectations for how this money is allocated. I know people would have made different decisions if they were told up front that the money wouldn’t be in their hands tomorrow. And the reality is, this is not first money out the door. It takes time.

It shouldn’t necessarily take as much time as it’s taking, but I’ve talked to consultants who have worked with grantees on a lot of disaster relief plans, and they said that realistically, the smoothest and best-run program is still going to take a good 18 months from appropriation to putting it together and starting to get funds to flow. And that’s basically where we are now.

In my interview with Nancy Kete from the Rockefeller Foundation, she spoke about the economic inequality we see in how cities like NYC recover after storms like Sandy – that, for example, the Lower East Side is back to normal while the Rockaways are still struggling. Do you see that?

Well, it’s nuanced. It’s certainly harder for residential areas to recover than commercial areas that have more resources to bring to bear on it. If you’re a corporation, you’re insured and probably have the wherewithal to come back quicker. But it’s way more complicated with homeowners. Some people didn’t have insurance. Some had insurance but didn’t get the whole payouts. And vulnerable populations don’t have money in the bank to just go and repair their home tomorrow. There’s no question.

But from my perspective, that’s where our money is going. Our mandate is that half our money has to go to low- or moderate-income areas. We prioritize figuring out how to make sure it gets to the places that are most vulnerable and don’t have other resources first. That’s our whole philosophy. It’s just a little slower.

Have you learned any other lessons from this disaster relief process?

Well … here’s another. As a federal agency, our MO is to let our grantees determine how their funding gets spent. We’re very hands off, because in our opinion, they know better than we do about the best way to spend their money. And that works well for regular funds.

But for disaster money, nobody is prepared to respond to a disaster in city or state governments in the same way. There’s no standing staff for that. This isn’t something they do all the time. So one of the lessons we’ve learned since Katrina and some other recent disasters is that our grantees are saying to us, “We appreciate the fact that you want to let us figure out how to spend the money, but some guidance would be helpful.” They don’t want to have to reinvent the wheel. So the onus is on us.

So far, all your work sounds like it’s focused on rebuilding, not building for the future. And yet as I’ve been reporting this, HUD keeps coming up as part of this future-oriented stormproofing network. It’s interesting to me that you’re using recovery money for resilience work.

Yes, so that’s the big mind shift that’s happened with Sandy. In the past it was much more reactive. It was, “We had a disaster, let’s repair what was already there.” That was also the case at Fema. In the past, they could actually only fund, to the dollar amount, a rebuilding in kind. That’s changed.

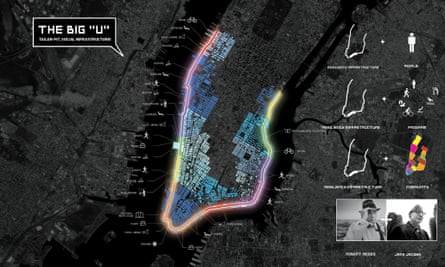

Putting close to $1bn of our recovery money into the Rebuild by Design competition was a very visible symbol of that shift, saying that we’ve got to spend this money on rebuilding smarter. We need to be better prepared for future storms and recognize that that’s just part of our reality now. And since the government is not always known as the innovator among innovators, the thought was, let’s put a callout to the whole world to try to get the best ideas.

It sounds like Rebuild also lets you help your grantees figure out how to spend their recovery money, like they asked.

It did. Rebuild is unusual in that we helped pick projects with NYC and New Jersey. We did it in conjunction with them, but that’s about as prescriptive as we’ve ever been in terms of how that money gets spent.

I also have a team, some city planners, working closely day-to-day with our grantees on spending this money, both overall and for the Rebuild projects specifically. We’ve never done that before. But these are projects we’ve invested a lot in, and we want to make sure they end up with the same level of innovation as the competition envisioned. So far, the relationships are good. Working this closely is definitely uncharted territory.

Ok, so what happens after all the money you’ve awarded is spent? HUD awarded $337m, for example, for the first phase of a winning Rebuild project, the Big U.

Right. When we were doing the awards, we decided to fund the first phase of more projects instead of putting it all toward one. So we told the teams to chunk them out in fundable and discreet phases, where each would be a standalone resilient project, so if only one ended up getting funded, they wouldn’t be doing more harm than good.

But what about when they want to do phase 2 or 3? If another big storm doesn’t come that will give you more federal money to allocate to resilience, who’s going to pay for it?

That’s the big question. This is exactly what Roland was asking in your interview with him: we’re talking about massive levels of investment required if we’re truly going to make this region as resilient as I think everybody would like to make it. So the question becomes, where does that come from?

One of the things that gives me great hope is that the Army Corps of Engineers are really the long term players in this. They have funding that predates Sandy and projects they’ve been working on pre-Sandy, and now they’re tweaking them and figuring out how to add the Sandy recovery funding in. Then they’re working on a longer term approach that they’ll go back to Congress with to request further funding. If they’re doing their job, it takes a long time, but it will outlast all this other emergency money that’s only tied to Sandy.

I know Roland pretty well, and he was pretty cynical in his interview about whether there would be federal will to do what it takes. Anytime you have to get money from Congress it’s obviously a process, and it includes a political element. But I do think, at least in this New York/New Jersey region, that the federal agencies are all looking at this as a long term thing. We’re putting the vision together here so there will be a real plan to advocate for funding in the future. I’d say the will is there.

So are the federal agencies literally coming together in rooms to figure out a long term plan?

Yes. One of the really innovative and unprecedented things we’re doing in the region is creating a really coordinated federal inter-agency framework for working together on Sandy recovery, and then thinking beyond it. We’ve never had a framework like that before.

And on top of that, we have a leadership group of the major infrastructure agencies that meets every month: Fema, us, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the Army Corps. We’re looking at literally mapping where different projects are happening so we can make sure we’re not duplicating efforts or acting in conflict with each other. That’s what’s shown me that the Army Corps is the big player here. They’re going to be here way past the storm.

That’s the piece that gives me hope.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion