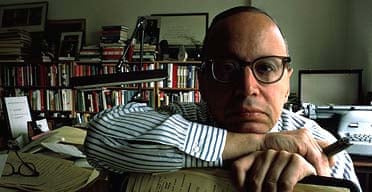

Arthur M Schlesinger Jr, one of America's most eminent and controversial historians, has died after a heart attack, aged 89.

As a close adviser to president Kennedy and a member of his administration, Schlesinger largely created the "Camelot" myth of the Kennedy years. Subsequent revelations of the president's shady political and personal record did not shift Schlesinger's robustly partisan view.

In later life he grew increasingly disenchanted with his country's social direction. In 1991, his book, The Disuniting of America, expressed concern about the rise of ethnic consciousness and the conflict it had produced. Observing that "historians must always strive toward the unattainable ideal of objectivity," he acknowledged that "as we respond to contemporary urgencies we sometimes exploit the past for non-historical purposes, taking from the past or projecting upon it what suits our own society or ideology".

Though it was intended as an attack on the cherrypicking tendency of ethnic history, this passage also offered a species of coded apologia. Schlesinger had started as a remarkable young scholar who reaped considerable academic honours for his groundbreaking studies of American political development. From there he had become far less detached and more and more immersed in the transient political battles of his day.

Even in his 80s, he could not resist a partisan fight. At the height of the impeachment campaign against the (Democrat) president Clinton, Schlesinger launched a ferocious attack on the special prosecutor and called for all proceedings to be halted. Clinton, of course, later acknowledged that he had, in fact, committed an impeachable offence by lying to a federal grand jury.

A generation earlier, at a similar stage of the Watergate crisis in 1973, Schlesinger had argued equally fiercely that the (Republican) president Nixon must be made to face trial by the Senate. If these opposing stances lacked historical objectivity, they were hardly surprising in a determined Democratic campaigner who had been one of the founding fathers of the party's ginger group, Americans for Democratic Action (ADA).

Schlesinger's 1973 outburst may also have been fuelled by chagrin. The previous year he had forecast an easy victory for George McGovern because he was "leading a constituency as broad as Roosevelt's coalition in 1932". Nixon, of course, romped back to the White House by 520 electoral votes to McGovern's 17.

An equally partisan moment came in the 1980 election, when Schlesinger put his money on the obviously forlorn chances of Senator Edward Kennedy against president Jimmy Carter. Anyone observing that campaign could foresee the outcome almost from the start. Clearly Schlesinger was talking from his heart not his head and, as the years went by, it became increasingly important to determine which organ prevailed.

Schlesinger spelled out his personal credo during the celebrations for his 80th birthday. "I'm an unrepentant and unreconstructed liberal and New Dealer" he said. "That means I favour the use of government to improve opportunities and to enlarge freedoms for ordinary people". He denied that his stance was incompatible with his academic position. "Being a historian does not require one to renounce being a citizen. Macaulay was a member of parliament. You shift gears when you write history, everyone does".

In fact, the path of Schlesinger's career seemed inevitable almost from birth. He was born Arthur Bancroft Schlesinger, Jr, but later gave himself his father's middle name, Meier. His father was a professor of American history in Ohio who moved his family to Cambridge, Massachussetts, when he was offered a professorship at Harvard. From the age of seven, therefore, young Arthur was plunged into the world of America's movers and shakers, an ambience in which he spent the rest of his life.

His early education was at the exclusive Phillips Exeter Academy, New Hampshire, from which he progressed effortlessly to Harvard, securing his first degree at the age of 20. In an early example of his taste for political controversy (and ready access to centres of influence) he returned from an 11-month world trip in 1939 to pen a controversial series of articles for the Boston Globe. Swimming resolutely against the popular tide, he urged America to abandon its isolationism, introduce immediate conscription, and intervene in the war in Europe.

In 1940, after completing a book-length thesis on the 19th century religious activist, Orestes Brownson, and another substantial study of the Boston historian Richard Hildreth, Schlesinger was appointed to a three-year fellowship at Harvard at the extraordinarily early age of 23. The citation said he had been chosen for showing "the promise of a notable contribution to knowledge and thought".

However, his academic progress was interrupted by America's entry into the war. Having failed his military medical examination, Schlesinger initially joined the Office of War Information. Later he shifted to the cloak-and-dagger Office of Strategic Services, which took him to London, Paris, and occupied Germany. He said later that he had "gained more insight into history from being in the war than I did from all my academic training".

However, his war service had not absorbed all his energies: he managed to continue work on his seminal work, The Age of Jackson, which he completed in 1945. Schlesinger's re-examination of the first American president to be elected by popular vote, and his analysis of Andrew Jackson's ruthless expansion of executive power and role in founding the Democratic party had a profound impact on fellow historians and on their subsequent treatment of the period.

It also brought Schlesinger his first Pulitzer prize and his elevation to a Harvard professorship in 1947. At the same time he increased his overt political commitment by helping to establish the ADA. He also settled into his exhaustive, and highly sympathetic, history of the New Deal, The Age of Roosevelt, which appeared in three volumes between 1957 and 1960.

One theme to emerge as these books rolled off the presses (eventually to total more than a score) had originally been propounded by Schlesinger's father. In Tides of American Politics, the elder historian had set out his thesis that the republic's history had followed a wave pattern of 11 alternating periods of liberal and conservative dominance. With curious precision he set the average length of these waves at 16 years and seven months.

Schlesinger Jr embraced this theory, which he then allied to two others - that America had a periodic need for heroic leadership and that its governance revolved round a vital centre of accepted societal values. The death of Roosevelt, the postwar conservative control of Congress, and the stasis of the Eisenhower presidency convinced Schlesinger that his wave pattern would bring a liberal revival at the 1960 elections and with it a new heroic leader.

At Harvard he become acquainted with the Kennedy family as a classmate of Joseph, the eldest son, killed in the war. He had occasionally met John Kennedy at the house and the two established a firm friendship while working for Adlai Stevenson's 1952 presidential campaign. As Kennedy began preparing for the 1960 presidential elections, Schlesinger became closely involved in his campaign. He saw Kennedy as the predicted hero who could pull the nation out of its 16-year torpor. In an effort to convince the still-sceptical Stevenson wing of the party about Kennedy's merits he rushed out a 50-page eulogy.

In party terms it was hugely successful though Kennedy's hairline victory, by 114,000 of 68 million popular votes, suggested that the electorate was still sceptical (and that Schlesinger's wave theory was deeply indebted to Chicago's peculiar vote-counting culture).

Schlesinger was appointed the president's special adviser on Latin America. Though cautioning against "hyperoptimism", he welcomed the new president as "a man of action who could pass easily over to the realm of ideas, and confront intellectuals with perfect confidence in his capacity to hold his own".

This early enchantment set the tone for A Thousand Days, Schlesinger's highly-coloured history of the administration. The book painted a glowing picture of Kennedy's early days as president. "Meetings were continuous. The evenings too were lively and full. The glow of the White House was lighting up the whole city". It received mixed reviews, even at the time, but won Schlesinger his second Pulitzer prize in 1965. It also established him as an unabashed Democratic cheerleader.

In the aftermath of this literary success, which attracted long profiles in Time magazine and the New York Times and flattering references to "America's most controversial historian", Schlesinger decided to move to New York, to a teaching post at the City University's graduate centre.

However, unfolding events - Kennedy's assassination, the Vietnam war, student riots, America's burgeoning racial tensions, the consequent middle class backlash - cast a deep shadow over Schlesinger's prediction of a liberal cycle. It should, by his theory, last until 1976 and the election of Richard Nixon in 1968 precipitated a major revision.

Schlesinger began to argue that rapid technological change, not least the speed of communication, was outstripping the government's capacity to control events and therefore imposing permanent instability on society. By the time the unscheduled conservative cycle had endured from 1968 to 1992 -- through Nixon, Ford, Carter, Reagan and Bush -- Schlesinger felt obliged to extend his father's 16 years to 30.

He explained, however, that "there is nothing mystical about the 30-year cycle. Thirty years is the span of a generation. People tend to be formed politically by the ideals dominant in the years when they first come to political consciousness".

He also modified his concept of the vital centre. In reconsidering an American history which embraced slavery and the resulting civil war, he decided there was a deep rift in the national tradition. "We must face up to the schism" he concluded, "between our national instincts for aggression and our national capacity for civility and idealism".

His revised wave theory seemed in reasonable shape when Clinton became the first Democratic president to be re-elected for 52 years. But it took a nasty knock in 2000 when the electorate divided down the middle and achieved a deadlock in both presidential and congressional elections. The pendulum simply refused to move either way.

Schlesinger retired from the City University in 1994 and was immediately made its emeritus professor in humanities. As he grew older he grew gloomier, foreseeing yet further fragmentation of American society.

Of its ethnic divisions he wrote: "The multi-ethnic dogma abandons historic purposes, replacing assimilation by fragmentation and integration by separatism. It belittles unum and glorifies pluribus. The historic idea of a unifying American identity is now in peril - in our politics, our voluntary organisations, our churches, and our language".

He also feared a return to isolationism in America's relations with the wider world. "If we cannot find ways of implementing collective security, even in the form of preventive diplomacy, we must be realistic about the alternative: a chaotic, violent, and dangerous planet" he commented in one lecture. In an apparently despairing coda he added: "Maybe the costs of military enforcement are too great. Withdrawal may seem a safer rule in an anarchic world in which our power and wisdom are limited. Maybe we should just let the law of the jungle take over".

In his last book, War and the American Presidency, published in 2004, Schlesinger challenged the foundations of the foreign policy of George Bush, calling the invasion of Iraq and its aftermath "a ghastly mess". He said the president's curbs on civil liberties would have the same result as similar actions throughout American history. "We hate ourselves in the morning," he wrote.

Schlesinger had five children - four from his first marriage to the author Marian Cannon, and one from his second to Alexandra Emmet.

· Arthur Meier Schlesinger Jr, historian and author, born October 15 1917; died February 28 2007