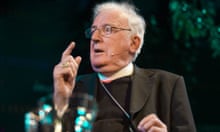

Cardinal Cormac Murphy-O’Connor, archbishop emeritus of Westminster, who has died aged 85, was there or thereabouts at several crucial points in the recent history of the Catholic church. The extent to which he actually influenced the events in which he participated, though, was always hard to assess, partly because this genial cleric naturally played down his own importance, and was much more comfortable in casting himself as the benign parish priest rather than a prince of the church.

Some claimed, though, that his was an influential voice among the small group of liberal-minded cardinals – known as “la squadra” – behind the surprise election at the papal conclave of March 2013 of the “change candidate”, the Argentinian Pope Francis. A few months after his election, the former Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio was apparently lightheartedly to credit Murphy-O’Connor, when the two met at a papal audience. The pope pointed to his old friend and said, “You’re to blame!” But, as Murphy-O’Connor subsequently noted, because he was over 80 at the time of the conclave, church rules had allowed him to participate only in the preliminary discussions, and not in the actual vote in the Sistine Chapel.

And it was Murphy-O’Connor who received Tony Blair into the Catholic church in December 2007, having persuaded the former Labour leader to wait to convert until after he had resigned the premiership six months earlier. Had Murphy-O’Connor taken the opposite line, Blair might have been the first Catholic prime minister since the Reformation. “I counselled Tony that we were not rushing this just because he was PM,” Murphy-O’Connor later recalled. “I didn’t think that was enough of an excuse for me to say to him, ‘Let’s do it quickly.’ I wanted him to be sure it was what he wanted.”

It was a typically pastoral approach, which was usually Murphy-O’Connor’s greatest strength. He took people where they were, rather than where church doctrine would prefer them to be. Yet after his surprise appointment in 2000 as archbishop of Westminster, and leader of the Catholic church in England and Wales, he faced sustained and highly damaging criticism for his handling of the case of a paedophile priest when he had been bishop of Arundel and Brighton in the 1980s.

After receiving a complaint about Father Michael Hill’s behaviour towards a child, Murphy-O’Connor had sent him away for counselling, and later to a course at a “therapeutic centre” run by a church organisation, rather than report him to the police. Later, when begged by Hill for a second chance, and without attempting to speak to his victims, Murphy-O’Connor appointed him as Catholic chaplain at Gatwick Airport on the grounds that Hill would not have access to children there. He did – as should have seemed obvious – and he abused them. Hill was jailed in 1997 for five years.

Murphy-O’Connor’s mistakes in this case only really hit the headlines in 2000, after he was promoted to the top job in English Catholicism. Never a confident performer in the media when under scrutiny, he gave a poor account of himself when publicly challenged on such prominent platforms as BBC Radio 4’s Today programme.

To many, he seemed more concerned with protecting the good name of the church than with addressing the suffering of victims. As a result, there were calls for his resignation. He was seen as a symbol of the repeated failure of Catholicism to protect children in its care, and then to acknowledge or even understand why what had been done was so very wrong.

The cardinal soldiered on, however, though his credibility was badly dented. His penance was to spend his nine years at Westminster working to repair the damage, principally by appointing a senior judge, Lord (Michael) Nolan, to report on how the church’s safeguarding responsibilities could be overhauled, victims listened to and supported, and children protected. The blueprint Nolan produced was enacted in full and has subsequently become a model of good practice for bishops around the world.

“Of course, with hindsight, I should have reported Hill to the police,” Murphy-O’Connor said in 2015 when he published his memoir, An English Spring, which included an extended and agonised mea culpa for the errors he had made over child abuse. “I don’t want to make any excuses. I had to bear the shame, for me and for the church, and try to do something about it.”

Despite a name that appeared to denote a son of Ireland, Cormac Murphy-O’Connor was born in Reading, Berkshire, the son of prosperous middle-class parents. Both his devout mother, Ellen (nee Cuddigan), and father, George, a GP, had roots in Ireland but were well assimilated into the English bourgeoisie by the time Cormac, the fifth of their six children, came along. They chose a private education for him, first locally with the Irish Presentation Brothers, and later at Prior Park college, Bath, a boarding school housed in a stately home, the grandest of the Christian Brothers’ establishments in Britain.

The priesthood was in Murphy-O’Connor’s genes. At the age of four he is said to have announced that he would either be a doctor, like his father, or pope. Several of his uncles had taken vows, and two of his brothers also became priests, so the choice would have appeared natural. “I’ve sometimes missed not having children of my own,” he wrote in his memoir. “It’s just one of the things you sacrifice when you make a promise of celibacy.”

Marked out as a potential high flyer by being sent to the Venerable English College in Rome for his training, he was ordained in 1956. He quickly caught the attention of those more senior than him and served as chaplain and secretary to the local bishop of Portsmouth, Derek Worlock, later archbishop of Liverpool and one of the most radical, if underrated, figures in English Catholicism in the second half of the 20th century.

Worlock enthused his young protege about the reforms brought about in the church by the reforming Second Vatican Council of 1962 to 1965. In 1971, after allowing him a brief spell as a parish priest in Southampton, Worlock sent Murphy-O’Connor to be rector at his alma mater, the English College in Rome. It is a post that is often considered to be a suitable training ground for future bishops, but equally it has marked the end of the career of many an ambitious priest.

The period was a turbulent time for the Catholic priesthood, with many clerics and seminarians jumping ship in dissatisfaction at Humanae Vitae, the 1968 encyclical that reaffirmed the church’s opposition to artificial birth control. As rector, Murphy-O’Connor characteristically steered a careful course, kept his head down in the great disputes dividing Catholicism, but showed many of the personal qualities that were later to make him a well-liked bishop and cardinal.

With remarkable prescience, the rugby-playing Murphy-O’Connor invited a football and skiing enthusiast, Cardinal Karol Wojtyla of Krakow, to lunch at the English College in 1974. The two, those present report, hit it off. Perhaps the meeting stuck in John Paul II’s mind 25 years later when he came to select a successor to the popular Basil Hume as leader of the Catholic church in England and Wales.

By that time, Murphy-O’Connor had served for two decades as an admired, competent and, when the occasion demanded it, quietly independent bishop of the south coast diocese of Arundel and Brighton. In his early years there, church insiders tipped him for further promotion, but as vacancies came up and were filled, his moment seemed to have passed. To add to the impression that he was yesterday’s man, his pet project, the Anglican-Roman Catholic International Commission, which examined forging closer links between the Vatican and the Church of England and its sister churches, was effectively put on ice by an unenthusiastic John Paul II.

When Hume died in June 1999, Murphy-O’Connor was widely discounted on the grounds of being, at 67, too old and too out-of-step with an increasingly traditionalist Vatican. Hume, though, is said to have privately recommended him as his successor and Rome, for once, listened to the local church.

As archbishop, his successes in influencing government policy and wider national debate were few. His championing of the cause of migrant workers brought positive headlines, but did not change the public mood, while on questions such as abortion law reform and restrictions on embryo research, he made little impact.

He could be clumsy in the spotlight. His widely reported aside, just before the 2005 general election, about preferring the Conservative leader Michael Howard’s comments on abortion to that of his friend, Blair, then prime minister, went against a long tradition of the church leadership carefully remaining above party politics. Had he been deliberately breaking that rule, his gesture might have carried some force, but it seemed to many that he had simply misjudged the tone of his remarks.

His translation to Westminster in 2000 will be seen by history as essentially a stopgap appointment. With the younger bishop Vincent Nichols sent simultaneously to run the vast archdiocese of Birmingham, Rome was effectively asking Murphy-O’Connor to hold the fort and continue the work of Hume while Nichols gained a little more experience.

And, in 2009, that is precisely how it turned out, with Murphy-O’Connor retiring to a former presbytery in Chiswick, west London, with his piano (he could, it was said, have had a career as a professional musician) and golf clubs. He was the first archbishop of Westminster since the English hierarchy was restored in 1850 not to die in office.

Among the high points of his later years was the prominent part he played in the visit of Pope Benedict XVI to Britain in 2010. And, of course, his presence in Rome in 2013 to witness the election of his friend as Pope Francis. He looked on in pleasure at the impact made by the Argentinian whom he liked, jokingly, to refer to as “my man”.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion