A palm-fringed ridge rises above the plains of Alagoas in north-east Brazil. Just a few replica thatched huts and a wall of wooden stakes now stand at its summit, but this was once the capital of the Quilombo dos Palmares – a sprawling, powerful nation of Africans who escaped slavery, and their descendants who held out here in the forest for 100 years.

Its population was at least 11,000 – at the time, more than that of Rio de Janeiro – across dozens of villages with elected leaders and a hybrid language and culture.

Palmares allied with indigenous peoples, traded for gunpowder, launched guerrilla raids on coastal sugar plantations to free other captives, and withstood more than 20 assaults before falling to Portuguese cannons in 1695.

“Hundreds threw themselves to their deaths rather than surrender,” said local guide Thais “Dandara” Thaty at the historical site in Serra da Barriga. In her telling, those killed included Dandara – her adoptive namesake – captain of a band of warrior women, whose husband Zumbi is similarly shrouded in myth as a fearless Palmarian commander.

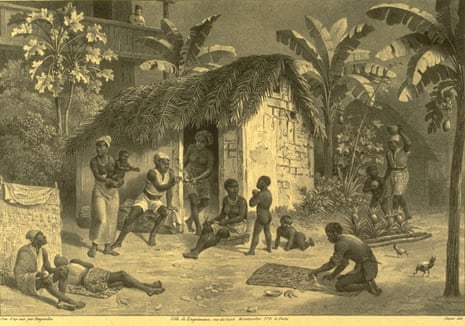

About 5 million enslaved Africans were brought across the Atlantic to Brazil between 1501 and 1888. Many escaped, forming quilombos, or free communities.

Three centuries later, the remarkable saga of Palmares is being seized on once more as a symbol of resistance against Brazil’s rightwing president and the country’s pervasive racism towards its black and mixed-race majority.

A pair of new television and Netflix documentaries, screened in late 2018 and this June, have examined the legacy of Palmares. In March, the victorious carnival parade of Mangueira samba school highlighted Dandara among a lineup of overlooked black and indigenous heroes. Later that month, Brazil’s senate voted to inscribe Dandara in the Book of Heroes in the Pantheon of the Fatherland, a soaring, modernist cenotaph in Brasília.

Angola Janga, a graphic novel charting the rise and fall of Palmares, has won a string of awards. “Many people want an alternative view, to try to escape the one-sided, one-dimensional vision of our history imposed by the Portuguese and Brazilian elite,” said author Marcelo D’Salete, whose painstakingly researched book, including maps and timelines alongside striking monochrome illustrations, has been widely used in classrooms.

“Quilombos in general are very big right now,” said Ana Carolina Lourenço, a sociologist and adviser to one recent documentary on Palmares. Young Afro-Brazilians have even coined a verb, she added – to quilombar – meaning to meet up to debate politics or simply celebrate black music, culture and identity.

This renewed prominence coincides with a sharp rightward turn in Brazilian politics. Jair Bolsonaro has denied that Portuguese slavers set foot in Africa, and vilified the roughly 3,000 quilombos dotted across Brazil today – poor and marginalised Afro-Brazilian communities, often descended from fugitive slaves – branding their residents “not even fit for procreation”.

The president has sought to erode the landholding rights of quilombo communities in favour, critics argue, of the powerful agribusiness sector. Police killings, mainly of Afro-Brazilians, in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo have also risen sharply in 2019 with Bolsonaro’s encouragement.

Earlier this month, footage of supermarket security guards whipping a bound and gagged black teenager for allegedly shoplifting, prompted reflections on the lasting legacy of slavery.

For centuries, writers portrayed Palmarians merely “as runaway blacks and outlaws who rebelled against the crown”, said the Alagoas historian Geraldo de Majella.

It was only in the mid-20th century that historians began to reconstruct its story via Portuguese archives, often in Marxist terms. Meanwhile, “black militant movements took up the flag of Palmares as a movement of national liberation,” De Majella explained. The largest guerrilla group during the 1964-85 military dictatorship – the Palmares Armed Revolutionary Vanguard – counted former president Dilma Rousseff among its members.

Lula, the former president, simultaneously bolstered recognition of Palmares and the legal rights of present-day quilombos. 20 November – the date the Palmarian leader was killed – was officially adopted as the National Day of Zumbi and Black Consciousness in 2003.

In the same year, public schools were legally required to teach Afro-Brazilian history.

But limited archaeological evidence and the absence of Palmarian sources has encouraged freewheeling interpretations. Today, perhaps drawing on the historical presence of advanced metalworking at the site, some compare Palmares with Wakanda, the hi-tech, Afrofuturist utopia of Marvel’s Black Panther.

But the inclusion of Dandara – whose first written mention occurs in a 1962 novel – in the Pantheon divided opinion. “I absolutely defend creative freedom in the way people look at our history,” said D’Salete. “But we need to take care to differentiate between fact and fiction.”

Fernando Holiday, an Afro-Brazilian YouTuber and conservative activist, has noted that Palmarian society had monarchical elements and also kept captives. “I’m sorry to disappoint leftist and black leaders, but today we’re commemorating a farce,” Holiday said in a video. “Zumbi wasn’t a hero of abolition.”

But Palmares and other examples of revolt and resistance, D’Salete argued, “are important as other ways of understanding our history … so people can imagine and build another kind of society that is very different to one just based on violence and oppression”.

That legacy of violence is apparent in Tiningu, a remote quilombo in Pará state. The community has battled to receive legal recognition, threatened by the ranchers and landowners who have cut down much of the surrounding rainforest. One resident was murdered by a rival soybean farmer on the eve of Bolsonaro’s election. Here, Palmares is not merely history but a source of hope.

“Zumbi was the beginning of everything,” said local teacher Joanice Mata de Oliveira, whose school is daubed with the names of African nations. “He was the one who began our fight.”