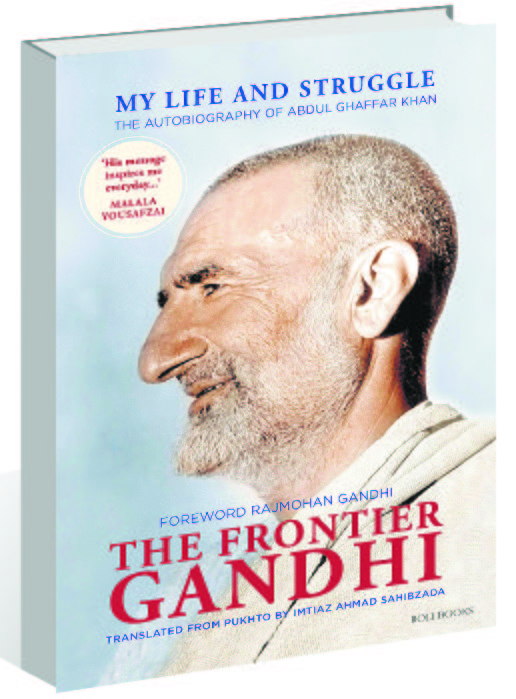

My Life and Struggle, the Autobiography of Abdul Ghaffar Khan, the Frontier Gandhi. Translated by Imtiaz Ahmad Sahibzada. Roli. Pages 556. Rs 695

Book Title: My Life and Struggle, the Autobiography of Abdul Ghaffar Khan, the Frontier Gandhi

Author: Translated by Imtiaz Ahmad Sahibzada

M Rajivlochan

The memoirs of Bacha Khan document growing up a Muslim in a Muslim-dominated region, participating in the politics of the nation and then getting sidelined with the growth of Muslim politics. As a glimpse into the ideas of one of the tallest leaders of the Pakhtuns, this book is invaluable.

Bacha Khan, as Abdul Ghaffar was respectfully known, was among the many in India who did not believe that only a Muslim could adequately represent Muslims in India. Yet, once this insidious belief on representation transformed into the far more dangerous belief that the Muslims of India needed a country of their own, he proved helpless. It resulted in the partition of two provinces of India, Punjab and Bengal, in 1947. It also resulted in other parts of India, such as Pakhtunistan, Baluchistan and Sindh, being forcibly cut away from the motherland and handed over to Pakistan.

Almost overnight, the religion-based creation of Pakistan neutralised this man of action. He was nearing 60 years of age at the time of Partition, had been active in opposing the British through non-violent means for over 40 years, had emerged as one of the most popular leaders in India and as a saintly guide among the Pakhtuns. In the decades that followed, he was marginalised by the increasing religiosity in the public life of Pakistan. It was at this stage that he gave a number of interviews that were published in the form of a biography. Dissatisfied with the biography, he took up the task of writing his own memoirs. This book is but an English translation of his memoirs written in Pukhto and published in 1983.

Abdul Ghaffar was the youngest son of his parents, duly spoilt. His parents, he says, “were not taken in by the propaganda of the maulanas” and made him and his brother get a proper missionary education. Indians in those days, he recalls, behaved like slaves before the puniest of the English. Therefore, he refused to join the British Indian Army even on being offered a commission after completing school. Instead, he studied further and took the initiative to set up a number of Islamic madrasas in the land of the Pakhtuns so as to give them modern education, bypassing the prohibition placed on the Pakhtuns joining mission schools. “The religious education imparted in our schools was better both in content and method than that imparted in the mosques,” he writes. To inoculate his madrasas from the ire of the local maulanas, Abdul Ghaffar requested the patronage of reformist religious leaders.

In Abdul Ghaffar’s recollections, the Bhagwadagita remains an important motif to justify the need to undertake correct action. Its teachings are a constant, whether it be in running his school, or getting into a dialogue with the divines from Deoband, or persuading his fellow Muslims to not go on hijrat at the urging of the maulanas. India, he explained to them, is not dar ul-harb, the Abode of War, where Islam is believed to be under threat. When he failed to convince his people, he had no hesitation in accompanying them on a foot journey to Afghanistan.

Many of those who joined the hijrat returned to India as communists. But not Abdul Ghaffar. He turned a firm Gandhian, a staunch believer in interpreting religion in a more humane way than was being done. And using this new interpretation of religion, to be able to live in India and work in collaboration with people of all faiths and all regions.

Separate electorates for Muslims made him uncomfortable. He foresaw the subsequent Communal Award as a device to break up India into religious groupings. Electoral democracy built on religious separation, he would say, would disallow Indians to live together; particularly, it would encourage separatism among Muslims. The large bulk of the story that is recalled in this book is about his defeat at the hands of the separatists. One feels sad while reading the latter half of the memoirs at the sort of inevitability of Partition, and Bacha Khan’s helplessness that such separateness was creating.