/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/35383818/113492180.0.jpg)

It's official: Warren Harding had a love child. The New York Times's Peter Baker reports that new genetic tests have confirmed Harding was the biological father of Elizabeth Ann Blaesing, whose mother, Nan Britton, had revealed an affair with the president, starting when he was a senator and continuing into the White House. It's the second major revelation regarding Harding's extramarital dalliances in recent years; last year, the Library of Congress released his ultra-explicit love letters to mistress Carrie Fulton Phillips that came to light this past summer. ("The president often wrote in code, in case the letters were discovered, referring to his penis as Jerry," the Times's Jordan Michael Smith explains.)

These personal sins have only bolstered Harding's reputation as one of the worst presidents in American history. "He slashed immigration quotas, appointed his cronies — one of whom, his secretary of the interior, accepted bribes from oil companies in what became known as the Teapot Dome scandal — and brought an end to the famously reform-minded eras of Teddy Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson," Smith writes.

But this assessment is wrong. It's true that Harding's administration was super corrupt, and his immigration policy left a lot to be desired. No one would argue he was a top 10 president. But his reputation as one of America's worst is just as misguided. Far from ending the reform era, Harding continued it in some meaningful ways, and, most notably, was considerably more progressive on racial issues than his notoriously racist predecessor, Wilson.

Domestic policy

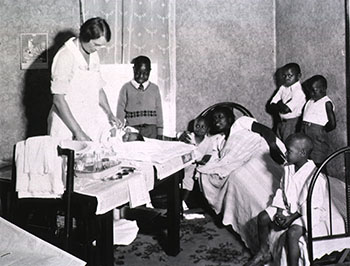

A nurse funded by the Children's Bureau's Maternity and Infancy program performs a home visit. (National Library of Medicine)

Smith's knock on Harding for being insufficiently reformist is particularly strange in light of the latter's signing of the Sheppard-Towner Act of 1921, which historian Stanley Lemons once described as "the first venture of the federal government into social security legislation." The act was meant to provide health assistance to new mothers and infants, given the poor state of pre- and postnatal care at the time. The law "provided federal matching grants to the states for information and instruction on nutrition and hygiene, prenatal and child health clinics, and visiting nurses for pregnant women and new mothers," as York University's Molly Ladd-Taylor explained.

The program didn't last long; it was briefly extended in 1927, but was not made permanent, and was killed within a few years by president Herbert Hoover, with the backing of the American Medical Association. Ladd-Taylor explains that the law was "vigorously opposed by a coalition of medical associations and right-wing organizations who claimed it was a Communist-inspired step toward state medicine that threatened the home and violated the principle of states' rights" (sound familiar?). But it seemed to serve its purpose. Economists Carolyn Moehling and Melissa Thomasson estimate that Sheppard-Towner accounted for 9 to 21 percent of the decline in infant mortality during the period in which it was in effect.

That was hardly the only public investment Harding supported. He also signed into law the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1921, which continued and greatly expanded the Wilson administration's efforts to build a true national highway system. "The Federal Highway Act of 1921 ushered in the golden era of road building in the United States," the National Park Service states. "In 1922, the states spent $189 million to build over 10,000 miles of federal-aid roads. This more than tripled the number of road-miles improved since 1916."

Maybe Harding's most enduring domestic policy achievement was the Budget and Accounting Act of 1921, which created the Bureau of Budget (now the Office of Management and Budget) and the General Accounting Office (now the Government Accountability Office), both of which are crucial parts of the federal budgetary and oversight process. The Bureau of Budget greatly professionalized presidential fiscal policy by providing the White House with specialized expertise in budget issues, while the GAO has performed a vital oversight and investigative role for the legislative branch. Additionally, Harding signed a bill creating the Veterans Bureau, which would eventually evolve into the Department of Veterans Affairs and was among the first dedicated federal efforts to care for veterans and help them readjust to civilian life; his director, however, was fairly corrupt, blunting the impact of the bureau's creation.

Harding's record on labor regulation was, admittedly, terrible. He sent troops to quell a miner's strike in West Virginia, and his attorney general, Harry Dougherty, secured a brutal court injunction to break a nationwide railroad strike. But Harding deserves credit for helping bring about the eight-hour workday, which was adopted in 1923 by the steel industry after extensive pressure from Harding and his administration. He also signed into law the Capper-Volstead Act, which enabled the creation of agricultural cooperatives, to ensure small farmers couldn't be steamrolled by the large corporations purchasing their goods. And he signed into law a bill, later ruled unconstitutional, regulating the futures trading market, only the second federal attempt to regulate financial derivatives after a brief effort during the Civil War.

International affairs

Calvin Coolidge signed the Immigration Act of 1924, a far more restrictive measure than Harding's.

Even on immigration, Harding's record isn't quite as terrible as you might think. It's true that he signed a 1921 bill creating a draconian cap on immigrants, tying quotas to the number of immigrants from particular countries of origin already in the United States. That, in effect, privileged immigrants from Northern and Western Europe (as most Americans at that point were of English or German descent) and greatly reduced migration from Southern and Eastern Europe. But it was temporary, in effect for only three years, and it paled in comparison to the 1924 law, which permanently set even lower quotas and barred Asians from immigration entirely by banning people ineligible for naturalization from immigrating (Asian naturalization had been banned decades prior). It also used the 1890 census rather than the 1910 census for determining the existing ethnic makeup of the US to be used for quotas; that was hardly an accident, as the Jewish population in the US had swelled in those two decades, meaning the 1924 act was a potent tool for anti-Semitic exclusion.

It is worth noting that Harding didn't enforce the 1921 law particularly harshly. He tasked his secretary of labor, James Davis, with enforcement; Davis, notably, was himself an immigrant and didn't take a hard line. "Harding frequently made exceptions, saving almost a thousand immigrants from deportation," biographer John Dean writes. "Harding and Davis both believed the law was necessary but thought its enforcement had to be humane." Among other things, that meant setting up centers in Europe to deter immigrants before they were turned away on American shores.

Harding is also justifiably attacked for resisting US participation in the League of Nations, helping ensure the failure of that organization. But he wasn't totally uninvolved in international peacemaking endeavors. He tried to join the World Court, but failed due to congressional opposition, and hosted the Washington Naval Conference, one of the first major multilateral arms control efforts. The latter failed to prevent rearmament in the 1930s, obviously, but it did secure limitations on naval fleets for a number of years.

Civil rights and civil liberties

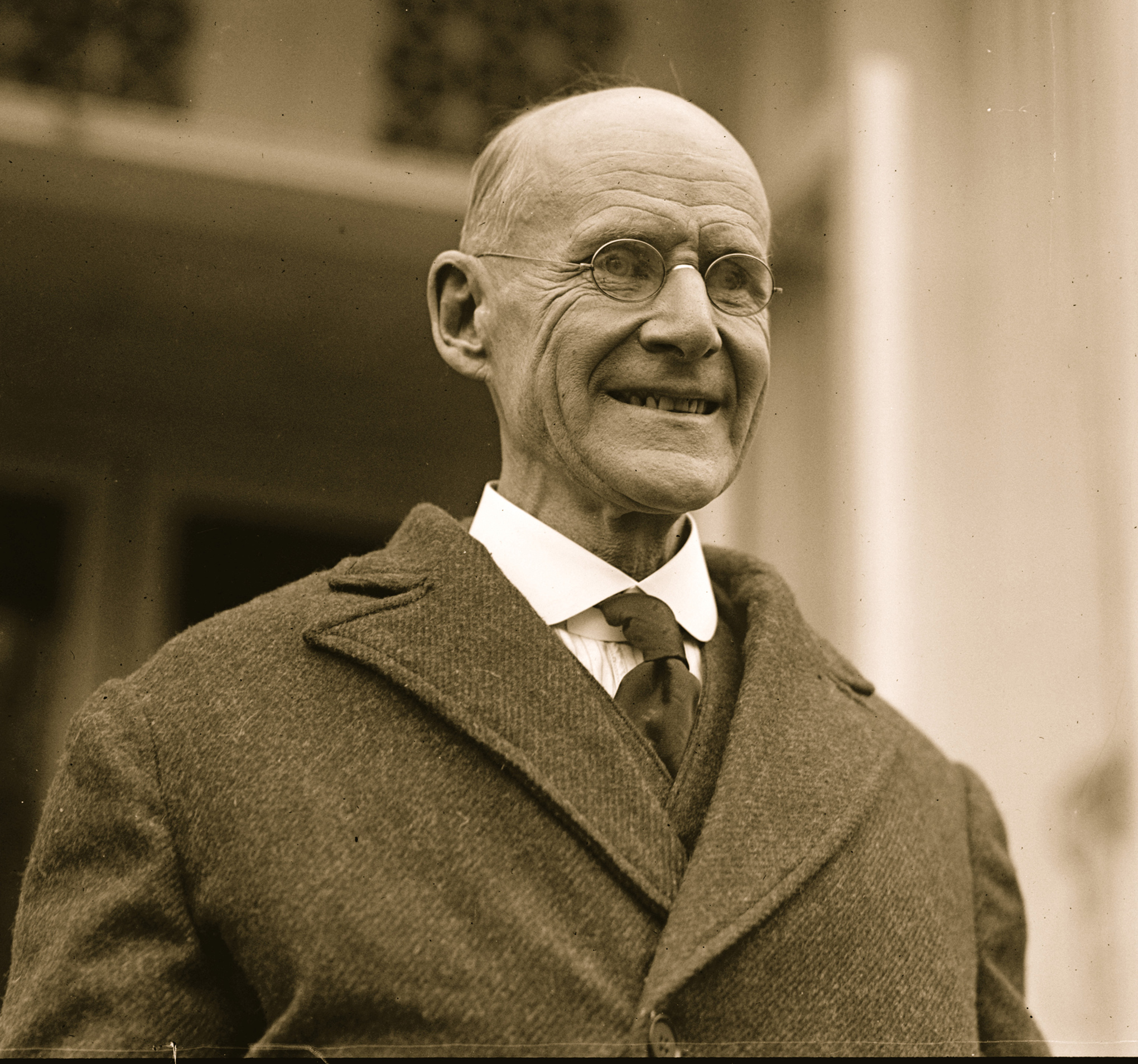

Eugene Debs, whom Harding freed from prison. (Photo by Buyenlarge/Getty Images)

In sharp contrast to Wilson — who resegregated much of the federal government — Harding's positions on race were startlingly progressive for the time period. In October 1921, he took to Birmingham, Alabama, to deliver a blistering indictment of race-based economic disparities and call for legislation to combat lynching. "When I suggest the possibility of economic equality between the races, I mean it precisely the same way and to the same extent that I would mean it if I spoke of equality of economic opportunity as between members of the same race," Harding said. "Whether you like it or not, unless our democracy is a lie you must stand for that equality." Looking at the black section of the segregated auditorium where he was speaking, he continued, "I want to be looking in their direction when I say these things because I am speaking to North and South alike, white and blacks alike. I am never going to say anything that I can’t say in every direction and to all people exactly alike."

Now, it's important to note that Harding's vision of equality didn't involve integration, per se, and he retained a troublesome belief in the reality of race as something more than a social construct. He also said in that Birmingham speech, "The black man should seek to be, and he should be encouraged to be, the best possible black man and not the best possible imitation of a white man." "Racial amalgamation there cannot be," he further stated. "Partnership of the races in developing the highest aims of all humanity there must be if humanity, not only here but everywhere, is to achieve the ends which we have set for it." (Perhaps unsurprisingly, the noted black separatist Marcus Garvey enthusiastically praised the speech.) Harding's protestations here probably have something to do with the pervasive rumor, spread by political opponents, that he had black ancestry.

So Harding was hardly racially progressive by modern standards, but next to the overt racism of most of the Democratic party at the time, his rhetoric was encouraging. Following the speech, the Dyer anti-lynching bill, which would have made lynching and failure on the part of local officials to prevent lynching felonies, passed the House but languished in the Democratic-controlled Senate. He left little in the way of practical achievements, but he invested real political capital in service of anti-racist measures, and was condemning the most vicious racists in American politics up until his death. Shortly before he passed away, he gave a pair of speeches attacking the Ku Klux Klan as "factions of hatred and prejudice and violence" that "challenge both civil and religious liberty."

Harding also deserves credit for his record on non-racial civil liberties, most notably his commutation of prison sentences of Socialist Party leader Eugene V. Debs and 23 other political prisoners who had been locked up by the Wilson administration for criticizing US participation in World War I. Harding wasn't by any means sympathetic to Debs or even really to Debs's free speech rights. "There is no question of his guilt and that he actively and purposely obstructed the draft," a statement about the commutation from the White House explained. "He is a man of much personal charm and impressive personality, which qualifications make him a dangerous man calculated to mislead the unthinking and affording excuse for those with criminal intent." But, the statement continued, Debs was a popular figure whom millions had voted for in five presidential elections, and compared with other "saboteurs" his actual activities weren't so threatening to the state. As with race, this wasn't a case of Harding being right for the right reasons, but the commutation was nonetheless a positive step.

The bad

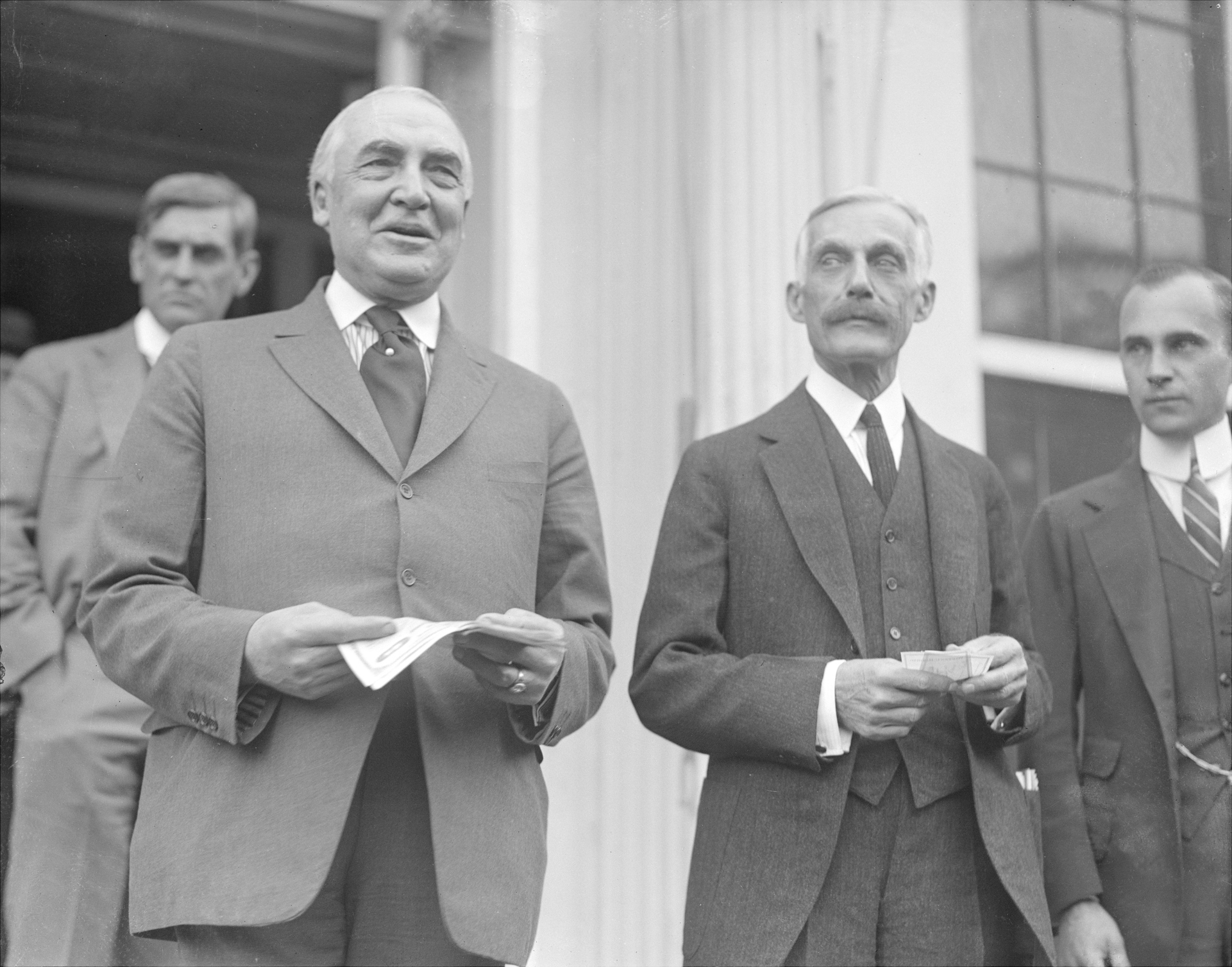

President Warren G. Harding and Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon. (Photo by NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images)

Some of Harding's record is very difficult to defend even in caveated terms. He increased tariffs, contributing to an unfortunate international trend of trade restriction in the 1920s. He appointed two of the Supreme Court's "Four Horsemen" who would severely hamper the implementation of the New Deal. His plutocratic treasury secretary, Andrew Mellon, spearheaded a law that made federal income taxes considerably less progressive.

But the most common criticisms of Harding concern the corruption of members of his administration, including Interior Secretary Albert Fall (who accepted bribes in exchange for no-bid contracts), Attorney General Daugherty (who was in bed with bootleggers he was supposed to be prosecuting), and Veterans Bureau chief Charles Forbes (who embezzled money from the newly created bureau).

Forbes's activities were by far the most scandalous, and Harding should have forced him to resign sooner than he did. But it's worth asking whether corruption concerns should dominate evaluations of Harding's presidency to the exclusion of his actual policy record. The point is not that the latter is spotless, but that creating the OMB, establishing a precedent for social welfare legislation, and speaking favorably of racial equality were probably more enduring and important to the fate of the nation than, say, Fall accepting bribes. This is a problem with our historical evaluations of presidents more generally; accusations of corruption have generally led all-time great Ulysses S. Grant to receive poor marks, despite being by far the most racially progressive president between Lincoln and Lyndon Johnson. That's a myopic way to look at Grant, and it's a myopic way to look at Harding.

Harding was hardly a great president, but he doesn't deserve the overwhelmingly negative reputation he's developed.