This article was originally published on January 11, 2023. We are recirculating it now that Green Day’s Saviors is out.

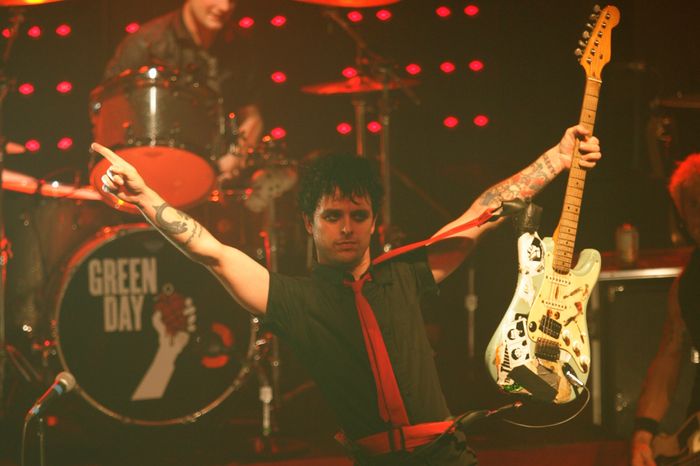

Billie Joe Armstrong is, in his own way, still fighting the punk fight. Most recently, he pissed off Trumpers for switching the lyrics to 2004’s “American Idiot” from “I’m not part of a redneck agenda” to the more relevant “MAGA agenda.” You can sneer at a rich, middle-aged Rock & Roll Hall of Famer trying to be political on Dick Clark’s New Year’s Rockin’ Eve, but it’s impressive Armstrong still has the power to upset people by changing a single word. Of course, the 51-year-old singer is just doing what he knows best: staying true to his longtime band’s interpretation of punk ideals and writing songs that have taught Gen-Xers, millennials, and now zoomers the art of accessible political rock music.

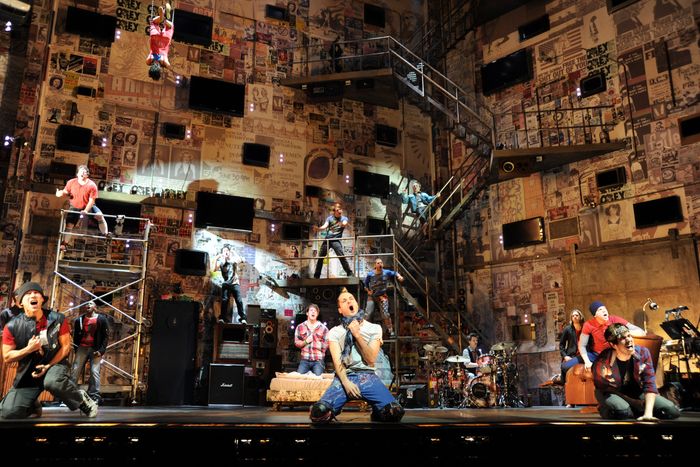

Armstrong has been so successful at capturing angst over the past three decades that he never has to make another song in his life. Yet he still feels compelled to write and perform with urgency, as he does on Saviors, Green Day’s 14th studio album (out January 19). It’s tempting to call it the band’s best work since American Idiot, but perhaps “focused” is more accurate. In its most compelling moments — the Clash-worthy “The American Dream Is Killing Me,” the infectious “1981,” the Quadrophenia-like “Coma City” — Saviors blends American Idiot’s theater-kid energy and pristine production with Dookie’s messy yet relatable inward confusion. At 15 tracks, it’s somehow Green Day’s leanest album in years, a quasi-rebuttal to the band’s last few divisive “rock!” LPs.

Armstrong and I connected over the phone while he was at home in Oakland (despite a recent threat to renounce his citizenship following the overturning of Roe v. Wade, he’s sticking to the States). The front man is currently taking time off before, in his words, “all hell breaks loose,” including a marathon 2024 world tour behind Saviors and the 30th and 20th anniversaries, respectively, of Dookie and American Idiot. In conversation, Armstrong is careful with his words yet calm and warm, like someone who long ago accepted — or perhaps gave up fighting — that fans still want to talk about Dookie. Regarding Saviors, he says, “I really believe we made one of our best records.”

The PR angle on Saviors is that it’s part of a trifecta with Dookie and American Idiot. Was the plan to always explicitly connect it to Green Day’s two biggest projects?

In the beginning, I kept changing my mind about what I wanted the record to be. Did I want it to be an old-school Green Day punk record, or did I want to do something that felt more lush and stadiumlike? And then you go, “Well, what about post-punk?” I confused myself so much. I was just trying to write the best songs that I could that came naturally. I got so inside of the record that you get to a point where you don’t know if it’s a cohesive idea or not.

We had a large batch of songs that we recorded in London and when we saw it come together, I remembered thinking, Oh, this is the connection. Saviors does feel like a trifecta with Dookie and American Idiot where it feels like a life’s work. I went from not knowing what the hell I was doing to going, “Oh gosh, we managed to bridge the gap between those two huge albums.”

In the title track, you sing, “We are the last of the rockers making a commotion.” Do you really believe that?

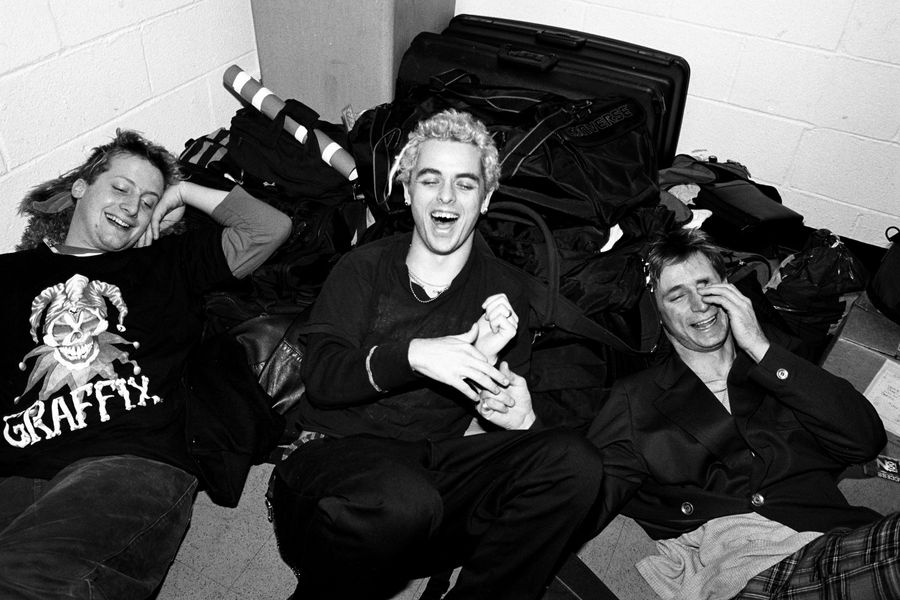

I don’t know. Last of the rockers, maybe it’s the last of our kind, the way that Mike and I met in middle school and stayed together ever since. Tré has been in the band since he was 17. It’s this organic way that we came up together. It’s different for everybody, but we were really young and managed to stick it out for over 30 years. Other bands have fallen apart, done their reunions, and all that stuff.

Tell me more about recording this album in London.

We wanted to get out of the U.S. and do something different. We found RAK Studios in St. John’s Wood. We loved it immediately. Just a breath of fresh air. A different place where we could focus and then go to the pub and hang out or go walking through Regent’s Park. It’s just a change of atmosphere that I thought was important to us. Plus, we have a lot of British influence in our music, from the British Invasion to glam to the first wave of punk that came out of London. Even Britpop.

One of American Idiot’s strengths was its ability to capture and satirize Bush-era politics. I was 12 years old when it came out so this may be me being naïve, but it felt like Bush was a relatively simple target for people’s frustrations at the time. A common complaint from artists today is that the Trump era and afterward feel too over the top to make fun of. Was there ever a version of your new song “The American Dream Is Killing Me” that was more explicitly about Trump, Biden, or anything else?

That song is more about being a stressed-out American. Our politics are so divided and polarized right now. We had an insurrection. We have homeless people in the street. We have so many issues, and they come onto your algorithm feed at such a pace. It just stresses you out, the anxiety of being an American and how it becomes so overwhelming. I think it was easier to satirize George Bush because we didn’t have social media. It was before all the tech bros came in. Now you have these billionaires who would rather shoot a rocket into space than deal with the infrastructure we have here. That’s one of the reasons we left to go record somewhere else. America is such a monkey on your back.

We always thought of American Idiot as being a big international record. We didn’t know how well it was going to go over in the States because we didn’t know what “the good ol’ boys” would think of it. Outside the States, it was really big. I think a lot of people couldn’t wait to say, “Don’t want to be an American idiot.” People get bombarded with American culture so much and it drives the media in such a way that people get sick of it. That’s part of what that record is about.

When I was relistening to American Idiot and got to the breakdown in “Holiday,” the “Sieg heil to the president gasman” line caught me off guard. I understand the context, but hearing it today is a trip.

Maybe it was an overreach back in 2004 to say something like that. But now we are on the brink of an autocratic government, or someone who is blatantly saying “If I’m president again, I’m going to be a dictator.” What’s that Maya Angelou quote? When people tell you who they are, believe them. It’s this exaggeration that became what can actually happen. It’s based on a cult of personality. America is not supposed to be about the cult of personality; we’re supposed to be about a group of people who are making laws that would make the American people’s lives easier and affordable. Getting good jobs, getting good health care, protecting people from corporations taking advantage of them. I feel like we are completely lost on that, the real American ideal. I listen to Dead Kennedys records today and Jello Biafra was a brilliant songwriter back then. “California Über Alles,” it’s now more like “America Über Alles.” It’s real and it’s at our doorstep and we better do something about it.

How do you think the Jesus of Suburbia would have been as a TikTok guy?

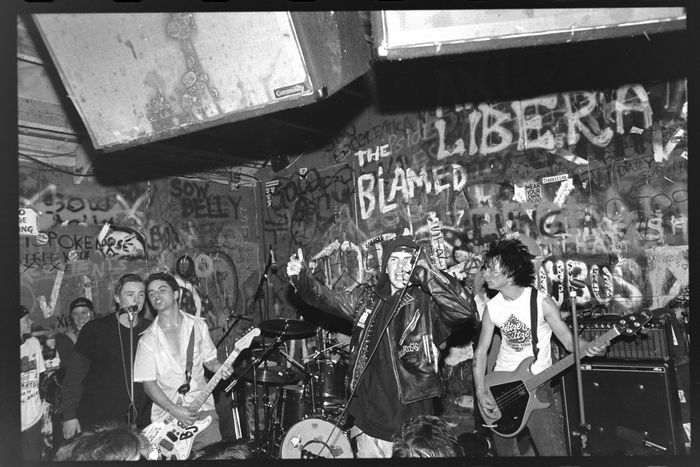

I think that character is very anti-everything. When I was a kid growing up, I stopped watching television and immersed myself in the different political views that came out of Gilman Street. Sort of a reeducation of what I was taught in school. “Jesus of Suburbia” is about someone leaving home, so I think that character would be more anti-social-media.

I’m also fascinated by what Tim Yohannan would have been like on social media.

Oh my God. Not to say that Tim Yohannan was a conspiracy theorist, but there are so many conspiracy theorists out there right now with these crazy views. I think Tim was focused on the scene and the purity of rock and roll. I do think Maximumrocknroll would be stronger than it is now if he were still alive. I think they would be more in print. Tim was all about the zine and people writing and doing their scene reports and record reviews. I think that audience would still be strong, and it would cross over into a new audience without using tech. He was all about an underground railroad, and being on Twitter would be the antithesis of that.

It feels so much harder to sustain such a pure local scene like Gilman. American cities keep getting more expensive, and it’s harder to have that physical space for people to come together. Everything is going and staying online anyway. Do you think punk has been able to translate to the internet, or is it impossible to find any space online that’s not already owned by some major conglomerate?

I see a lot of new bands popping up and using the internet and social media to their advantage, whether it’s a band like Scowl or Dead City Punx. I think they’re fun to watch, and I watch their shows on Instagram. It does bring people together. I think it can be beneficial for bands to create an audience on their own without using a major label. But streaming and shit like that and these TikTok videos that get popular, it’s like shooting in the dark. It’s like looking for a unicorn. All you do is just sit there and scroll. It’s wasted time.

I think the most difficult part of being in a young band is being on tour. The gas prices alone to get from show to show are crazy. When we were touring in vans, gas was cheaper. It was easier to go play a gig where you got paid $200 and were able to get to the next city. It’s much harder now. And some of these clubs are taking merchandise money away from bands that really need it and are just trying to survive. I’ve seen bands break up over that just because it’s not sustainable. They want us to put our lives into this, but it’s just too hard.

The song “Dilemma” on Saviors is about addiction and relapse. You’ve talked before about your rehab experience. And the past few years have been hard for people in recovery, especially during COVID lockdown. Did that isolation affect you in any scary ways?

When I was on the Hella Mega tour, I started to struggle with alcohol when we were in Europe. It was all fun and games. What got me back into drinking was that sort of fear of missing out. I felt like I was alone. AA was difficult for me because, especially in the Bay Area, there’s the one word, anonymous. It was hard for me to maintain my anonymity. That was the struggle for the five years I was sober. I was out drinking again for a few years and then I just realized I was just unhealthy: My mental health was falling down the drain, getting the shakes. And then I was like, “Fuck this, I feel messy right now.” The only thing alcohol was doing for me was getting in the way of the things I wanted to do and the person I wanted to be.

I have a great set of sober friends that I didn’t have before when I was sober. They make going out and doing things a lot more fun. We support each other. We’ll drink Heineken 0.0 and smoke a little bit. Not weed but cigarettes. We have a good time for the night and then, you know, nothing good happens after 2 a.m. You get tired and it’s like “Man, I just wanna go to bed.” I’m older, I’m wiser. I have different things that make me happy. I don’t need to be out all night getting fucked up.

I appreciate you sharing all of this.

There’s a song I did on the Longshot record called “Chasing a Ghost,” which talks about being lonely in sobriety. “Dilemma” is sort of connected to that. They’re the most honest lyrics I’ve ever written in my life. Straight up, the chorus is “I was sober, now I’m drunk again.” I don’t think anybody is that honest with themselves about their cause of suffering and what kind of anxiety they’re going through. I think that song captures it.

Anniversary tours are very in vogue right now, though you never struck me as someone too nostalgic about the past. Was there any hesitancy in touting the Dookie and American Idiot anniversaries so much for a tour in which you’re already promoting a new album?

We’re definitely going to do something special. The way we looked at it, it was “Holy shit, we have a 20-year anniversary and a 30-year anniversary of two of the biggest rock records ever made.” With the trifecta with Saviors, that’s about being in the present and looking forward, but I think it’s good to honor your past. I think those records were so meaningful to people and meaningful to us. It’s this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to showcase them.

Are there other reactions or interpretations of Dookie and American Idiot that stand out to you now that weren’t so obvious to you years ago?

American Idiot hits the nail on the head any time there’s any sort of political and social betrayal going on in the world. I remember a couple of years back when Donald Trump went to visit England and “American Idiot” went to No. 2 on the charts. Any time and anywhere there’s some kind of corruption and political strife, that record is always going to be relevant. With Dookie, that record is about being a young person and being very honest. It goes through what a lot of young people and even adults go through. We wanted to make a record that we can play 30 years later and feel like it doesn’t get old. We play the singles a lot. But when we do this tour, we’re going to be going into more of the deep cuts.

I love the demos that came from the Dookie reissue boxed set a few months ago. In my notes, I wrote, “These are Van Halen songs with great harmonies.”

I love the four-track demos because they showed me how much we already knew what we wanted. I remember going out to Tré’s parents’ place in the country. We just hung out in the Redwoods and rehearsed. I brought my four-track and we demoed all the songs out there. There are more four-track demos lying around. We haven’t found them yet, but they’re around my house. We knew what our vocals were going to be. We knew exactly everything we wanted to do before we went into Fantasy Studios to record it with Rob Cavallo. We were prepared. A lot of it comes from the Lookout! days where you do records in a day and a half with a $1,000 budget. We heard so many nightmare stories about people just taking the money and overspending and then they’re in some kind of debt. We still wanted to pay the rent.

Nimrod also got a big anniversary reissue recently. The “Black Eyeliner” demo, which eventually morphed into “Church on Sunday,” is particularly great. How has that album aged for you?

For Nimrod, I was doing a lot of home demos, and we were rehearsing in this woman’s garage who was a schoolteacher across the street from a mausoleum. We wanted to do something that was expanding on Green Day without abandoning the whole sound. We experimented more. “Walking Alone” has got the harmonica in it. “Last Ride In” is this surf instrumental. And then obviously “Time of Your Life.” Trying to combine something like horns and strings on the record. I love that we were changing, but I also love that we had one foot in our past at the same time. It gave way to the future.

It’s interesting. With a record like Warning, some of our fans liked it and some were indifferent, but it was cool to see how, when we came out with American Idiot, it felt like Nimrod and Warning made more sense to everyone for the direction we were heading.

Saviors is the first Green Day album since the band signed to a major label in which you own the copyright. What kind of freedom does this now offer you?

Our contract was up after Father of All …, but we still had a good relationship with Warner. I’ve never really been mad at them about anything since we’ve been on there because, honestly, all our records have been successful — two of them massively successful. I never wanted to be a band that was ever, like, “Blame the record company.” Fuck that. I want to be the responsible one. The music industry is changing, especially because it’s chasing down streaming or will sign an artist over one of those crazy unicorn songs that go viral on TikTok. For us, let’s just make a deal. We own our masters, and we do a budget, and just take it one record at a time.

You’ve called the ¡Uno!/¡Dos!/¡Tré! trilogy your power-pop Exile on Main Street but admitted that the production wasn’t what it should have been. Would you take another shot at those albums à la the Replacements’ Tim (Let It Bleed Edition)?

I would love to do it. Production-wise, we could have gone one or two ways. We could have made it more like Dookie where it was bigger guitars and more punk sounding and bleeding into the rock a bit more. The other way was to do everything completely live and make it messy. We sort of compromised by playing with cleaner guitars. It got stiff sounding. I would love to go back and do some kind of reissue of just pulling the best of the trilogy and making it lean heavier on the rock side. It will happen at some point.

This is a little random, but how do you feel about My Chemical Romance’s The Black Parade? Along with American Idiot, it feels like the other major rock-opera album of the aughts, and it’s now seen as a touchstone of modern emo while embracing classic-rock ambitions.

I’m not that familiar with that record. I know American Idiot was a big influence on that album, right down to the producer. I didn’t pay that much attention to it because I was busy doing 21st Century Breakdown.

It’s an interesting thing about emo. That is the quickest nostalgia I’ve ever seen in history. Usually, it takes a 20-year gap, like in the ’80s when people were going, “Weren’t the ’60s so cool with peace and love and all that stuff?” But after My Chemical Romance broke up, literally two years later, they were having emo nights at these DJ dance parties where people wanted to go hear their favorite emo records. It’s funny how quickly people jumped on the nostalgia for that.

I’m pretty sure most of those emo musicians and fans are also Green Day fans.

Well, emo when I was a kid was Fugazi, Embrace, and Rites of Spring. They were these post-hardcore guys who were getting way more into poetry and more Gang of Four kind of sounds. Later, it became something completely different and very emotional. Sometimes you’d scream and then sometimes you would sing the chorus, but it was more about pop punk at the same time, which kind of confused me. I thought emo was something different. I think the impact Green Day had on it, I think our music was so honest and hit to the core of emotions, whether about relationships with girls and love songs and stuff like that. I think that’s where a lot of it ended up.

A lot of emo bands today would kill to write a song like “She.”

Yeah. That song was written for a girlfriend. She went to Cal Berkeley, and she was this feminist I learned a lot from. She was bringing her education home, and I was just trying to be a good listener. Listening to someone who had their frustrations in the world. Be a good man and listen to what this woman has to say. Don’t interrupt, don’t mansplain.

You mentioned pop punk. It’s funny that American Idiot is a punk record playing with theatrics and today we have someone like Olivia Rodrigo, this theater kid playing pop punk. Does her music stand out to you in any way?

I hear it but don’t go out buying any of those records or stream it. It does pass me by. When I hear it, I think it sounds good. A lot of that is for a younger audience, and I’m trying to figure out my own generation right now and where I come from. I think it would be fun to work with her sometime. She’s talented. Sometimes you can see how someone is interested in what punk rock is and maybe they don’t quite have some of the influences or knowledge that I have on the history of punk rock. I’m kind of an encyclopedia. To do something with someone like Olivia Rodrigo would be fun.

Still, it’s cool you keep your ear to the ground on what people are into these days, like Billie Eilish.

I try to. I dabble. But honestly, most stuff I keep my ear to the ground on is the stuff that isn’t heard. I make my personal YouTube playlist of stuff that’s unavailable — they play stuff that is unavailable because people will download their record collection — and then stuff that is more geared towards stuff people have never heard of. The Zips, the Stiffs. Oh God, who else? The Directions. The stuff you have to go on Discogs to buy. That’s what I love doing. Finding these EPs of a lot of power-pop stuff that you can’t stream. I’ll look for it on YouTube and get sucked down that rabbit hole, which is a healthy rabbit hole, and then I’ll go buy the record off Discogs. Some of them are fucking expensive.

Are there other records you gravitate toward when you’re caught in these personal moments of “Oh no, what is happening in the world?” Any new artists or records you find yourself drawn to for that comfort?

I’ll go back and forth between old records you can’t find anywhere. There’s a great power-pop band called the Starjets from the late ’70s that you can find on YouTube. Gosh, there’s this new band from the U.K. called Sharp Class. They’re really good. Another band called Bad Nerves from the U.K. who I think are the best band in England right now. I’m always on that constant search for the punk-rock beat.

This interview was edited and condensed for clarity.