Red Fox Breeding - Growth & Development of Cubs

At birth, the cubs are covered in a fine grey woolly fur, have a pink nose (which turns black within the first week), weigh between 50 and 150 grams (1.8-5.3 oz.) and are blind and deaf. (Like those of most mammals, fox kidneys excrete urea directly into the amniotic fluid during development; this could damage the foetus's delicate corneas and thus the eyes remain closed until after birth.)

In their detailed study of the development of 160 Red fox foetuses, American biologists James Layne and Warren McKeon found that the average birth weight was 100 grams (3.5 oz.), with a head 41 mm (just over 1.5 in.) long and a tail measuring around 57 mm (just under 2.5 in.) in length. The cubs are reasonably well furred, although the hair is short—6 to 8 mm (one-third of an inch) on the back and head, 5 mm (about one-fifth of an inch) on the stomach and much shorter on the muzzle, chin and lower legs—and many will have a white tip to the tail, with hairs of 2 to 3 mm (one-tenth of an inch) in length.

The early days

At birth, the fur is chocolate brown in colour in 'red' and 'cross' morphs and jet black in silver/melanistic animals. Layne and McKeon observed that the sex of the cub was readily determinable at birth. Indeed, the anatomists found that vixens and dogs could be sexed about two-and-a-half weeks before birth, based on the distance between the genital openings; external genitalia were visible about 38 days into gestation (i.e., two weeks before birth).

Newborn cubs are unable to thermoregulate (maintain their body temperature) fully for the first two-or-three weeks; they must huddle together and, in the early stages, stay close to the vixen to prevent hypothermia. Indeed, during the first two or three days, the vixen is very unlikely to leave the cubs (even to drink), although recently David Element reported a vixen leaving the cubs alone for relatively long periods from the first day. She'll stay in the earth and act as a 'thermal blanket', until their fur can provide some insulation - observations from captive foxes suggest that by about a week old the fur has grown sufficiently for the cubs to thermoregulate well enough to be left alone briefly. At this point the vixen will leave them for short periods, typically only a few minutes, to drink. The cubs' eyes and ears open at between 10 and 14 days old and teeth begin appearing in the upper jaw, those in the lower jaw following a couple of days.

By around two weeks old, the fur has changed from dark grey to a chocolate brown colour and by three weeks (above) the black eye streak appears and the cubs start to walk unsteadily - their back legs are weaker than their front, which is presumably an adaptation to prevent them leaving the earth until they're sufficiently well-grown. The white muzzle and some red patches are apparent by four weeks old, as the ears become erect and the muzzle starts to elongate. At about six weeks old the coat is a similar colour to that of the adult, but still retains its “woolly” cub-like appearance. The woolly fur is covered by longer guard hairs, giving a shiny lustre to the coat, at about eight weeks of age.

The cubs, like most mammals, are born with (initially cloudy) blue eyes. Eye colour is a result of pigment, typically although not exclusively eumelanin, deposited in the iris and, essentially, the more you have the darker your eyes appear. At birth, our irises have only a small amount of eumelanin, which allows the scattering of short wavelength (blue) light more than long wavelength (red) light, causing our eyes to appear blue (this is known as the Tyndall Effect). Eumelanin absorbs light, so the more you have, the less light gets scattered and the darker the eyes appear. Pigment production increases during the first few weeks of life so we (indeed, most mammals) have blue eyes at birth, which change to their adult colouration shortly afterwards. In foxes, the slate-blue eyes change to what Bridget MacCaskill refers to as a “smokey brown” colour in her 1996 book The Blood is Wild at between four and six weeks old, deepening to the striking amber hue by the time they're three months. We think the amber colouration in mammals is a result of a carotenoid pigment called lipochrome being deposited in the iris.

Keeping things clean

For several weeks after the birth of the cubs, the vixen's maternal duties involve playing and napping with the cubs, grooming them (paying special attention to the groin and ears) and eating their waste products. Indeed, according to Ashby's descriptions, as well as those of Michael Chambers in Free Spirit, the vixen will keep the earth spotlessly clean and, even as they get older, the cubs are apparently reluctant to soil the earth. The cubs are unable to evacuate their own bowels until they're about two weeks old (again, based on captive animals) and without this stimulation they will retain the waste products and this can prove fatal. This is a well-known phenomenon in mammals and studies on rats suggest that the neural mechanisms controlling bladder emptying undergo marked changes during the first three weeks of life.

The bladder and bowel are voided when a nerve response called the perigenital-bladder reflex is stimulated; the young cannot do this themselves until the spinal mechanisms that control it have developed sufficiently. It seems that, up until about three weeks (in rats) the mother licking the genital and rectal area (collectively referred to as the perineum) acts to stimulate this reflex. According to David Macdonald in his book, Running with the Fox, this toileting is carried out every two hours for the first week of the cub's life. The vixen may also spend a considerable time grooming the fine fur of newborn cubs, although this is apparently not essential. Initially dropping are small, dry yellowy-coloured pellets, but the consistency changes as the cubs start supplementing their diet with solid food (around a month of age).

Milk production & suckling

Fox cubs are lactophagus (dependent on their mother's milk) for the first four or five weeks of life, although they may start encountering meat from a day or two old. While the cubs are very small, the vixen will lay down to nurse them, but as they grow rapidly and become increasingly boisterous forcing her to stand while suckling.

Vixens typically have four pairs (i.e., eight) of mammae called nipples or teats, although as many as 10 have been reported, each with eight to 20 lactiferous (milk-secreting) ducts. In an article to BBC Wildlife Magazine, Stephen Harris noted that the teats in the groin produce more milk than those farther forward. Presumably, this means teats in the groin have more (or larger?) lactiferous ducts than those further up the belly, although I've been unable to find a source for this. It does appear, however, that if the litter is small, only the rear one or two pairs of teats will develop and produce milk, suggesting milk production starts in the groin. Given that cub development is dependent upon early nutrition, those monopolising the rear teats may be able to grow more rapidly than their litter mates.

In a paper published in Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology during 2000, Øystein Ahlstrøm and Søren Wamberg at the Agricultural University of Norway reported on the milk intake of captive fox cubs. A vixen starts producing milk around the time the cubs are born and these researchers found that the daily intake per unit of body mass was around 30 grams (1 oz.) of milk per 100 grams (3.5 oz.) of cub. In practice this meant that, depending on the size of the cub, they were drinking anywhere between 31 and almost 200 grams (up to 7 oz.) of milk per day. The total milk yield amounted to between 200 and 300 mL per vixen two or three days after the cubs were born; this increased to about 800 mL by the time the cubs were about two weeks old. Overall, Ahlstrøm and Wamberg found that a vixen's daily milk production depended partly on the number of cubs in the litter, but more closely on the total body mass of the litter.

By the time the cubs are weaned, the vixen will have lost 20% to 30% of her body weight. Indeed, Mark Evans, on Channel 4's Foxes Live mini-series that aired in May 2012, reported that a vixen needs an additional 250 kcal per cub per day to maintain milk production at peak flow, suggesting that a vixen with a litter of four would need to increase her daily energy intake by some 1,000 calories - based on their representations, that's about 20 mice (at ca. 50 kcal per mouse) or 400 worms (~2.5 kcal per worm).

For the first few weeks, the milk produced by the vixen is the thick, creamy, vaguely yellow in colour high in fat (colostrum). In a paper to the Journal of Biological Chemistry in 1935, Elrid Young and G. A. Grant observed colostrum in samples of milk taken up to about a month after the cubs were born; the colour changed to white and the consistency decreased to that of cow's milk on about the fifth week of lactation. On average, Young and Grant found that fox milk contains about 6% protein, 6% fat and 4.5% sugar (lactose) - the colostrum was significantly higher in protein (17%) and fat (12%), but lower in sugar (4%). The analysis also revealed that fox milk is about 2.5-times higher in calcium and contains just over twice as much phosphorous as cow's milk.

Moving onto solids

The deciduous (lacteal or “milk”) teeth are complete at six or seven weeks old (allowing the cub to take solid food), but the vixen may start presenting the cubs with solid food from about three or four weeks old, even though they are only able to suck the juices and play with it (helping to develop jaw muscles and hunting technique). Based on Samuel Linhart's study, published in the Journal of Mammalogy in 1968,the loss of lacteal teeth begins at about 16 weeks old and is complete within about two weeks. In many instances permanent teeth were partially erupted while the old lacteal teeth were still present.

Often, the first solid food seen by the cubs is meat regurgitated by the vixen. Indeed, the vixen may start regurgitating food for the cubs around the time they're three weeks old and, although the striated muscle lining a fox's oesophagus is under nervous control (allowing them to regurgitate voluntarily), as in most canids the regurgitation is usually stimulated by the cubs licking the corner of the adult's mouth. To the best of my knowledge, the mechanism triggered by this licking is unknown, but Charles Horn—Associate Professor of Medicine and Anaesthesiology at the Hillman Cancer Center in Pittsburgh, USA—suggested to me that licking might stimulate the trigeminal nerve in the face, which subsequently triggers the regurgitation.

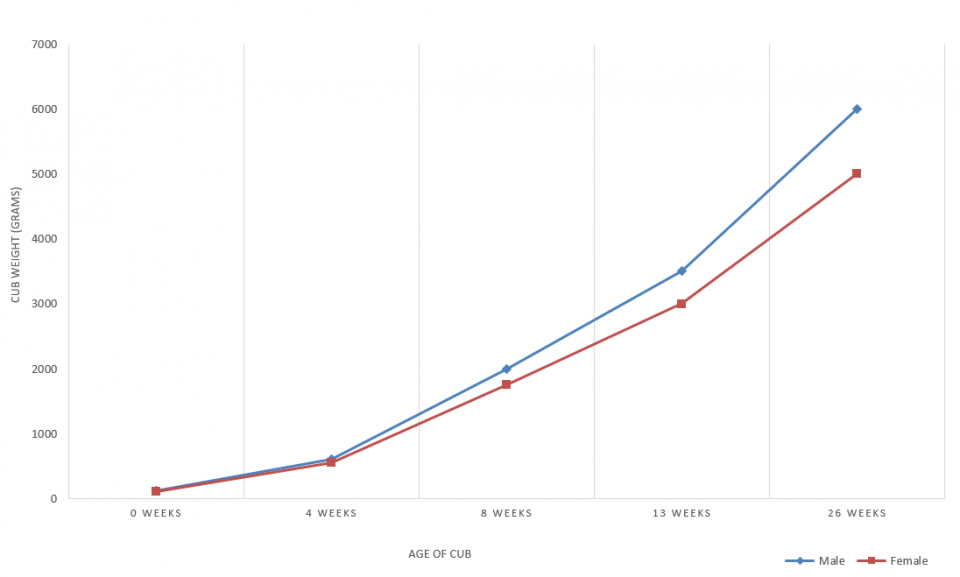

The vixen's milk is high in energy and, during the first month of life, the cubs will put on 15 to 20 grams (up to about two-thirds of an ounce) per day in weight. By around six weeks old the cub will weigh just over a kilogram (just under 2.5 lbs) and by about 4.5 months old it will reach its adult body size but, at around three kilograms (just over 6.5 lbs), not its adult weight. Some cubs will grow faster than others—growth rate is determined by access to food and some members of the litter will monopolize food—and this can give the false impression of mixed litters (although this phenomenon is not unknown and, in Bristol, up to three litters have been found mixed into a single crèche).

Child support

The dog fox, and in some cases non-breeding “helper” vixens (see: Behaviour and Sociality), will hunt for food to sustain the vixen and the cubs until the cubs are sufficiently independent to be left for longer periods (around six weeks old); the vixen will then resume hunting for herself and the cubs. That said, there appears to be some disparity between the behaviour of the dog fox in different regions and this has led several authors to consider that dog foxes are rather disinterested fathers. Roger Burrows in his book, Wild Fox, for example, saw no evidence that the dogs paid any interest in their young and neither hunted for them nor played with them. Conversely, however, in his 1962 booklet, Henry G. Hurrell described watching a dog fox catch a rabbit and immediately take it to his family waiting on a nearby hillside, passing it to the vixen who then gave it to a cub. Similarly, MacCaskill noted how the dog fox she was watching in the Highlands of Scotland took an active role in hunting for the family; on one occasion, upon returning to the earth with a hare, the dog fox had it “snatched rudely” from him by the vixen.

So, for the most part, it seems that dogs do play at least some role in provisioning for the cubs, although how much physical contact they have with them is less clear. There are some reports of fathers playing with (or perhaps more accurately being played with by) the cubs, but generally it seems they spend little time with them. Indeed, the dog rarely spends any time in the earth, although Harris and his colleagues in Bristol found that, occasionally, one or even two dogs may remain in the earth with the cubs. Several observations, including those by Valeria Vergara in Canada, suggest that the main role of the dog is providing food and defending the cubs - Vergara found that males spent almost twice as long involved in 'vigilant behaviour' (i.e., keeping a look out for danger) as vixens. In addition, in his 1906 book, The Fox, Thomas Dale was convinced that the dog was a devoted father:

“Should the vixen meet her fate while the cubs are small, their father nobly takes charge of them, carrying them perhaps to some safer locality, and caring for them in the best way he knows.”

During her studies in Ontario, Canada, Trent University biologist Valeria Vergara observed eight Red fox families and noted that the male's job appeared to be more involved with providing food to the cubs and scanning the vicinity for signs of danger. Vergara found that, in general, the dogs contributed less direct care (i.e., spent less time socialising with the cubs) than the females; overall, the percentage of their time spent attending to the cubs was about 28% and 16%, for vixens and dogs respectively.

The vixen may continue to lactate until around the twelfth week, but cubs are fully weaned by six to eight weeks old (about May time) and, at this point, food is provided by both parents (and often any 'helpers'). As the date of weaning approaches, captive individuals have been observed burying food for their cubs to find, although studies in the wild often fail to find any sign of this. The cubs emerge from the natal earth at about five weeks old and may be seen playing outside in late April or early May; for the next few weeks they will contain their activity to within view of the earth.

Leaving the earth

If disturbed, the vixen may move her cubs to an alternative earth within her territory and, in The Red Fox, Lloyd told how some countrymen were convinced that the litter is split (some maintain by sex) at six-to-eight weeks and kept separately. Lloyd knew of no evidence to support this, but considered it possible. Very young foxes are carried by the vixen in a similar manner to a kitten - hanging by the scruff of the neck from the vixen's mouth. In urban settings, adults will often bring a range of toys (balls, dog chews, shoes, etc.) back to the earth for the cubs to play with.

By the time the cubs are eight or nine weeks old they have usually abandoned the earth altogether, opting instead to lie-up above ground in nearby dense vegetation (bramble, for example); they're now also ranging more widely, using most of the territory. The cubs can be easy to watch, very playful and seemingly unaware of potential danger, until they reach about 8-15 weeks old, at which point they can be very anxious, fearful and neophobic (cautious of unfamiliar objects, particularly humans), appearing to trust only those with whom they have grown up. This behavioural transition seems also to coincide with the cubs becoming less playful and, based on work by the Russian fox domestication project, happens in response to a surge in stress hormone production. This transition corresponds to the cubs spending more time exploring their parents' territory, during which a cautious demeanour may be live-saving. This does, however, vary from fox to fox and Hurrell observed that there were wide individual differences in a fox's reaction to danger - some being “wilder” (bolder, presumably) than others.

Coming of age

The adults will continue to bring the cubs food until they're about four months old, by which time their adult dentition is largely complete and they're capable of providing some food for themselves, although they still lack the hunting proficiency to catch birds and mammals and their diet is heavily based on fruits and invertebrates. It seems that as time progresses, the cubs split into smaller and smaller groups as they begin to forage on their own during August (January in Australia), and will be full-grown by the end of September (February in Australia); their winter coat begins growing during August and is complete by the end of December (June in Australia).

The juvenile foxes will reach sexual maturity at nine or ten months old. In low density populations vixens will often breed in their first year—although this is not always the case (just over half the vixens in one of Stephen Harris' London studies failed to breed in their first year) and they're generally more prone to abortion than older females—but most dogs won't breed until their second year. Indeed, even in her study of foxes kept on fur farms Ludmila Osadchuk found that as many as one-third of yearling won't mate because, it has been suggested, they are socially displaced by older males of a higher rank.

Similar studies, conducted by Morten Bakken at the Agricultural University of Norway, on farms have demonstrated that low-ranking vixens seldom wean cubs if they are housed next to a high-ranking animals, but will wean normally with an equally low-ranking animals next door. These data suggest that complex social factors influence a vixen's breeding potential. Generally, foxes are considered cubs up until they're four months old, after which they're juveniles and, once they reach one year old they're considered adults.

Once the cubs are independent they may either leave the group and search for their own territory—more common among males—or remain on the territory with their parents as long as resources allow. Based on the tracking studies undertaken in Bristol, dispersing during the first winter doesn't improve a dog fox's chance of breeding (see Behaviour - Dispersal).