Pike CNHI - Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program

Pike CNHI - Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program

Pike CNHI - Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

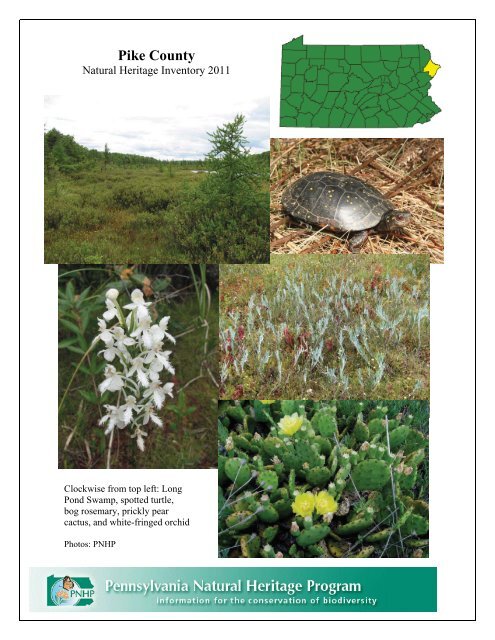

<strong>Pike</strong> County<br />

<strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Inventory 2011<br />

Clockwise from top left: Long<br />

Pond Swamp, spotted turtle,<br />

bog rosemary, prickly pear<br />

cactus, and white-fringed orchid<br />

Photos: PNHP

PIKE COUNTY<br />

NATURAL HERITAGE INVENTORY<br />

July 2011<br />

Prepared for:<br />

<strong>Pike</strong> County Planning Commission<br />

837 Route 6, Unit 4<br />

Shohola, PA 18458<br />

Prepared by:<br />

<strong>Pennsylvania</strong> <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> <strong>Program</strong><br />

Western <strong>Pennsylvania</strong> Conservancy<br />

800 Waterfront Drive<br />

Pittsburgh, <strong>Pennsylvania</strong> 15222<br />

The <strong>Pennsylvania</strong> <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> <strong>Program</strong> (PNHP) is a partnership between the Western <strong>Pennsylvania</strong><br />

Conservancy (WPC), the <strong>Pennsylvania</strong> Department of Conservation and <strong>Natural</strong> Resources (DCNR), the<br />

<strong>Pennsylvania</strong> Game Commission (PGC), and the <strong>Pennsylvania</strong> Fish and Boat Commission (PFBC).<br />

PNHP is a member of NatureServe, which coordinates natural heritage efforts through an international<br />

network of member programs—known as natural heritage programs or conservation data centers—<br />

operating in all 50 U.S. states, Canada, Latin America and the Caribbean.<br />

This project was funded through grants supplied by the DCNR Wild Resource Conservation<br />

<strong>Program</strong>, the <strong>Pike</strong> County Scenic Rural Character Preservation <strong>Program</strong>, and the <strong>Pike</strong> County<br />

Conservation District<br />

Copies of this report are available in electronic format through the <strong>Pennsylvania</strong> <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong><br />

<strong>Program</strong> website, www.naturalheritage.state.pa.us, and through the <strong>Pike</strong> County Planning Commission.

Preface<br />

The <strong>Pennsylvania</strong> <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> <strong>Program</strong> (PNHP) is responsible for collecting, tracking, and<br />

interpreting information regarding the Commonwealth’s biological diversity. County <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong><br />

Inventories (<strong>CNHI</strong>s) are an important part of the work of PNHP. Since 1989, PNHP has conducted<br />

county inventories as a means to both gather new information about natural resources and to pass this<br />

information along to those responsible for making decisions about the resources in the county, including<br />

the community at large. This County <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Inventory focuses on the best examples of living<br />

ecological resources in <strong>Pike</strong> County. The county must address historic, cultural, educational, water<br />

supply, agricultural, and scenic resources through other projects and programs. Although the inventory<br />

was conducted using a tested and proven methodology, it is best viewed as a preliminary report on the<br />

county’s natural heritage. Further investigations could, and likely will, uncover previously unidentified<br />

areas of significance. Likewise, in-depth investigations of sites listed in this report could reveal features<br />

of further or greater significance than have been documented. We encourage additional inventory work<br />

across the county to further the efforts begun with this study. Keep in mind that there will be more places<br />

to add to those identified here and that this document can be updated as necessary to accommodate new<br />

information.<br />

Consider this inventory as an invitation for the people of <strong>Pike</strong> County to explore and discuss their natural<br />

heritage and to learn about and participate in the conservation of the living ecological resources of the<br />

county. Ultimately, it will be up to the landowners, residents, and officials of <strong>Pike</strong> County to determine<br />

how to use this information. Several potential applications for the information within the County <strong>Natural</strong><br />

<strong>Heritage</strong> Inventory for a number of user groups follow:<br />

Planners and Government Staff. Typically, the planning office in a county administers county<br />

inventory projects. The inventories are often used in conjunction with other resource information<br />

(agricultural areas, slope and soil overlays, floodplain maps, etc.) in review for various projects and in<br />

comprehensive planning. <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Areas may be included under various zoning categories, such<br />

as conservation or forest zones, within parks and greenways, and even within agricultural security areas.<br />

There are many possibilities for the conservation of <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Areas within the context of public<br />

amenities, recreational opportunities, and resource management.<br />

County, State and Federal Agencies. In many counties, <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Areas lie within or include<br />

state or federal lands. Agencies such as the <strong>Pennsylvania</strong> Game Commission, the <strong>Pennsylvania</strong> Bureau of<br />

Forestry, and the Army Corps of Engineers can use the inventory to understand the extent of the resource.<br />

Agencies can also learn the requirements of the individual plant, animal, or community elements and the<br />

general approach that protection could assume. County Conservation Districts may use the inventories to<br />

focus attention on resources (high diversity streams or wetlands) and as a reference in encouraging good<br />

management practices.<br />

Environmental and Development Consultants. Environmental consultants are called upon to plan for a<br />

multitude of development projects including road construction, housing developments, commercial<br />

enterprises, and infrastructure expansion. Design of these projects requires that all resources impacted be<br />

known and understood. Decisions made with inadequate information can lead to substantial and costly<br />

delays. County <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Inventories (<strong>CNHI</strong>s) provide a first look at biological resources,<br />

including plants and animals listed as rare, threatened, or endangered in <strong>Pennsylvania</strong> and in the nation.<br />

Consultants can then see potential conflicts long before establishing footprints or developing detailed<br />

plans and before applying for permits. This allows projects to be changed early on in the process when<br />

flexibility is at a maximum.<br />

<strong>Pike</strong> County <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Inventory – Preface / iii

Environmental consultants are increasingly called upon to produce resource plans (e.g. River<br />

Conservation Plans, Parks and Open Space Plans, and Greenway Plans) that must integrate a variety of<br />

biological, physical, and social information. <strong>CNHI</strong>s can help define watershed-level resources and<br />

priorities for conservation and are often used as the framework for these plans.<br />

Developers. Working with environmental consultants, developers can consider options for development<br />

that add value while protecting key resources. Incorporating greenspace, wetlands, and forest buffers into<br />

various kinds of development can attract homeowners and businesses that desire to have natural amenities<br />

nearby. Just as parks have traditionally raised property values, so too can natural areas. <strong>CNHI</strong>s can<br />

suggest opportunities where development and conservation can complement one another.<br />

Educators. Curricula in primary, secondary and college level classes often focus on biological science at<br />

the chemical or microbiological level. Field sciences do not always receive the attention that they deserve.<br />

<strong>Natural</strong> areas can provide unique opportunities for students to witness, first-hand, the organisms and<br />

natural communities that are critical to maintaining biological diversity. Teachers can use <strong>CNHI</strong>s to show<br />

students where and why local and regional diversity occurs, and to aid in curriculum development for<br />

environment and ecology academic standards. With proper permission and arrangements through<br />

landowners and the <strong>Pennsylvania</strong> <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> <strong>Program</strong>, students can visit <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Areas<br />

and establish appropriate research or monitoring projects.<br />

Conservation Organizations. Organizations that have missions related to the conservation of biological<br />

diversity can turn to the inventory as a source of prioritized places in the county. Such a reference can<br />

help guide internal planning and define the essential resources that can be the focus of protection efforts.<br />

Land trusts and conservancies throughout <strong>Pennsylvania</strong> have made use of the inventories to do this sort of<br />

planning and prioritization and are now engaged in conservation efforts on highly significant sites in<br />

individual counties and regions.<br />

<strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Inventories and Environmental Review<br />

The results presented in this report represent a snapshot in time, highlighting the sensitive natural areas within<br />

<strong>Pike</strong> County. The sites in the <strong>Pike</strong> County <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Inventory have been identified to help guide wise<br />

land use and county planning. The <strong>Pike</strong> County <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Inventory is a planning tool, but is not meant to<br />

be used as a substitute for environmental review, since information is constantly being updated as natural<br />

resources are both destroyed and discovered. Planning Commissions and applicants for building permits should<br />

conduct free, online, environmental reviews to inform them of project-specific potential conflicts with sensitive<br />

natural resources. Environmental reviews can be conducted by visiting the PNHP website at<br />

http://www.naturalheritage.state.pa.us. If conflicts are noted during the environmental review process, the<br />

applicant is informed of the steps to take to minimize negative effects on sensitive natural resources. A pdf<br />

version of all completed County <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Inventories can also be found on the PNHP website. All<br />

<strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Areas identified statewide can be viewed at<br />

http://www.naturalheritage.state.pa.us/cnhi/cnhi.htm.<br />

<strong>Pike</strong> County <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Inventory – Preface / iv

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

We would like to acknowledge the many citizens and landowners of the county and surrounding areas<br />

who volunteered information, time, and effort to the inventory and granted permission to access land.<br />

We especially thank:<br />

<strong>Pike</strong> County <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Inventory Advisory Committee, including:<br />

Sally Corrigan – <strong>Pike</strong> County Planning Commission<br />

Scot Boyce – <strong>Pike</strong> County Planning Commission<br />

Nick Dickerson – <strong>Pike</strong> County Planning Commission<br />

Susan Beecher – <strong>Pike</strong> County Conservation District<br />

Nick Spinelli – <strong>Pike</strong> County Conservation District<br />

Tim Ladner – Bureau of Forestry<br />

Sue Currier – Delaware Highlands Conservancy<br />

Amanda Subjin – Delaware Highlands Conservancy<br />

Bud Cook – The Nature Conservancy<br />

Su Fanok – The Nature Conservancy<br />

Scott Savini – Blooming Grove Hunting and Fishing Club<br />

We would also like to thank the <strong>Pennsylvania</strong> Department of Conservation and <strong>Natural</strong> Resources for<br />

providing the funding to make this report possible. Funding was also provided by the <strong>Pike</strong> County Scenic<br />

Rural Character Preservation <strong>Program</strong>, the <strong>Pike</strong> County Conservation District, and the <strong>Pike</strong> County<br />

Commissioners. A special thank-you goes to the people of <strong>Pike</strong> County for their interest and hospitality.<br />

We want to recognize the <strong>Pennsylvania</strong> <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> <strong>Program</strong> and NatureServe for providing the<br />

foundation for the work that we perform for these studies. Current and former PNHP staff that contributed<br />

to this report include Jeff Wagner, Rocky Gleason, Andrew Strassman, Charlie Eichelberger, Chris<br />

Tracey, Pete Woods, John Kunsman, Mary Walsh, Ryan Miller, Ephraim Zimmerman, Sally Ray, Beth<br />

Meyer, Jake Boyle, Steve Grund, Tony Davis, Kathy Gipe, Jim Hart, Betsy Leppo, Matt Kowalski, Susan<br />

Klugman, Erika Schoen, and Kierstin Carlson.<br />

Without the support and help from these people and organizations, the inventory would not have seen<br />

completion. We encourage comments and questions. The success of the report will be measured by the<br />

use it receives and the utility it serves to those making decisions about resources and land use throughout<br />

the county. Thank you for your interest.<br />

Denise Watts, Ecologist<br />

<strong>Pennsylvania</strong> <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> <strong>Program</strong>

<strong>Pike</strong> County <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Inventory / vi

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

How to use this document<br />

The <strong>Pike</strong> County <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Inventory is designed to provide information about the biodiversity of<br />

<strong>Pike</strong> County. The Introduction of the report has an overview of the process behind this inventory as well<br />

as an overview of the <strong>Natural</strong> History of <strong>Pike</strong> County. Results are presented at the broad landscape view,<br />

then move into finer scale results presented by township. <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Areas that cross municipal<br />

boundaries are cross-referenced in each township section. Finally, conclusions and overall<br />

recommendations follow the township sections.<br />

Preface .........................................................................................................................................................iii<br />

Acknowledgements......................................................................................................................................iv<br />

Table of Contents........................................................................................................................................vii<br />

Executive Summary .....................................................................................................................................xi<br />

Introduction...................................................................................................................................................1<br />

County Overview..........................................................................................................................................3<br />

Overview of the <strong>Natural</strong> Features of <strong>Pike</strong> County........................................................................................4<br />

Physiography and Geology .......................................................................................................................5<br />

Soils ..........................................................................................................................................................5<br />

Vegetation.................................................................................................................................................7<br />

Flowing Water and Major Stream Systems ............................................................................................10<br />

Disturbance .............................................................................................................................................13<br />

Invasive Species in <strong>Pike</strong> County.............................................................................................................15<br />

<strong>Natural</strong> Resources ...................................................................................................................................20<br />

A Review of the Animals of <strong>Pike</strong> County...................................................................................................21<br />

Mammals of <strong>Pike</strong> County .......................................................................................................................21<br />

Birds of <strong>Pike</strong> County...............................................................................................................................25<br />

Reptiles and Amphibians of <strong>Pike</strong> County ...............................................................................................27<br />

Fishes of <strong>Pike</strong> County .............................................................................................................................31<br />

Freshwater Mussels of <strong>Pike</strong> County........................................................................................................34<br />

Insects of <strong>Pike</strong> County ............................................................................................................................35<br />

Methods ......................................................................................................................................................39<br />

Site Selection ..........................................................................................................................................39<br />

Ground Surveys ......................................................................................................................................39<br />

Data Analysis and Mapping....................................................................................................................39<br />

Results.........................................................................................................................................................41<br />

<strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Areas & Conservation Planning Categories....................................................................41<br />

Landscape-scale Conservation................................................................................................................41<br />

Important Bird Areas (IBAs) of <strong>Pike</strong> County .....................................................................................46<br />

Important Mammal Areas (IMAs) of <strong>Pike</strong> County.............................................................................49<br />

<strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Areas ...........................................................................................................................51<br />

Blooming Grove Township.................................................................................................................52<br />

Delaware Township ............................................................................................................................71<br />

Dingman Township.............................................................................................................................82<br />

Greene Township................................................................................................................................95<br />

Lackawaxen Township .....................................................................................................................104<br />

Lehman Township ............................................................................................................................117<br />

Milford Township & Milford Borough.............................................................................................127<br />

Palmyra Township ............................................................................................................................135<br />

<strong>Pike</strong> County <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Inventory – Table of Contents/ vii

Porter Township................................................................................................................................143<br />

Shohola Township ............................................................................................................................153<br />

Westfall Township & Matamoras Borough ......................................................................................163<br />

Glossary ....................................................................................................................................................177<br />

Literature Cited .........................................................................................................................................179<br />

GIS Data Sources......................................................................................................................................184<br />

Appendices................................................................................................................................................185<br />

Appendix I: Federal and State Endangered Species Ranking...............................................................185<br />

Appendix II: <strong>Pennsylvania</strong> Element Occurrence Quality Ranks ..........................................................189<br />

Appendix III: ‘EasyEO’ form and instructions.....................................................................................190<br />

Appendix IV: Species of Concern in <strong>Pike</strong> County documented in the <strong>Pennsylvania</strong> <strong>Natural</strong> Diversity<br />

Inventory database. ...............................................................................................................................192<br />

Appendix V: Sustainable Forestry Information Sources ......................................................................197<br />

Appendix VI: Sustainable Development Information Sources.............................................................199<br />

Appendix VII: PNHP Aquatic Community Classification ...................................................................200<br />

Appendix VIII: Species of Concern Fact Sheets..................................................................................214<br />

This reference may be cited as: <strong>Pennsylvania</strong> <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> <strong>Program</strong>. 2011. <strong>Pike</strong> County<br />

<strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Inventory. Western <strong>Pennsylvania</strong> Conservancy.<br />

Middletown, PA.<br />

<strong>Pike</strong> County <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Inventory – Table of Contents / viii

¹<br />

LAKEVILLE<br />

BUCK HILL FALLS NEWFOUNDLAND<br />

61<br />

Wayne County<br />

60<br />

Monroe County<br />

WHITE MILLS<br />

SKYTOP HAWLEY<br />

59<br />

62<br />

63<br />

GREENE<br />

PALMYRA<br />

PROMISED LAND<br />

65<br />

64<br />

58<br />

100<br />

17<br />

16<br />

67<br />

13<br />

99<br />

55<br />

57<br />

14<br />

98<br />

7<br />

66<br />

69<br />

11<br />

56<br />

10<br />

ROWLAND<br />

68<br />

70<br />

2<br />

4<br />

LACKAWAXEN<br />

54<br />

PECKSPOND<br />

71<br />

73<br />

72<br />

97<br />

3<br />

52<br />

5<br />

9<br />

8<br />

PORTER<br />

1<br />

49<br />

74<br />

12<br />

21<br />

94<br />

102<br />

103<br />

48<br />

15<br />

53<br />

51<br />

50<br />

45<br />

BLOOMING GROVE<br />

101<br />

TWELVEMILE POND<br />

18<br />

19<br />

BUSHKILL<br />

6<br />

20<br />

104<br />

96<br />

75<br />

95<br />

117<br />

118<br />

NARROWSBURG<br />

77<br />

116<br />

93<br />

119<br />

120<br />

<strong>Pike</strong> County <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Inventory<br />

Site Index<br />

ELDRED (NY)<br />

46<br />

92<br />

106<br />

105<br />

108<br />

EDGEMERE<br />

76<br />

87<br />

44<br />

47<br />

43<br />

SHOHOLA<br />

23<br />

DINGMAN<br />

78<br />

22<br />

42<br />

86<br />

88<br />

89<br />

91<br />

114<br />

LEHMAN<br />

121<br />

FLATBROOKVILLE<br />

115<br />

90<br />

25<br />

107<br />

85<br />

109<br />

41<br />

83<br />

24<br />

79<br />

DELAWARE<br />

110<br />

112<br />

SHOHOLA<br />

111<br />

POND EDDY<br />

113<br />

29<br />

27<br />

30<br />

40<br />

LAKE MASKENOZHA<br />

81<br />

82<br />

84<br />

26<br />

28<br />

31<br />

39<br />

80<br />

32<br />

MILFORD<br />

33<br />

34<br />

35<br />

WESTFALL<br />

38<br />

PORT JERVISNORTH<br />

37<br />

MILFORD<br />

CULVERS GAP<br />

36<br />

1:230,000<br />

0 1 2 4<br />

Miles<br />

6<br />

<strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Area<br />

# and Significance<br />

Exceptional<br />

High<br />

Notable<br />

Local<br />

PORT JERVISSOUTH<br />

Core Habitat<br />

Supporting<br />

Landscape<br />

Township<br />

Boundaries<br />

USGS<br />

Quadrangles<br />

<strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Areas<br />

# SiteName<br />

1 Delaware River North of Handsome Eddy<br />

2 Panther Lake<br />

3 Welcome Lake<br />

4 Masthope Creek<br />

5 Point Peter<br />

6 State Game Lands #316 Slopes<br />

7 WolfLake<br />

8 Forest Lake<br />

9 Corilla Lake<br />

10 Teedyuskung Lake<br />

11 Little Teedyuskung Lake<br />

12 Westcolang Pond<br />

13 Tinkwig CreekRoadside<br />

14 Lackawaxen River at Baoba<br />

15 Lackawaxen River at Rowland<br />

16 Decker Pond<br />

17 Buckhorn Mountain Slopes<br />

18 Fourmile Pond Wetland<br />

19 Spring Brook Wetland<br />

20 GermantownSwamp<br />

21 Lake Greeley<br />

22 Shohola Falls<br />

23 Bald Hill<br />

24 Walker Lake<br />

25 Twin Lakes and Wetland<br />

26<br />

Delaware River betweenHandsome Eddy<br />

and Dingmans Ferry<br />

27 State Game Lands #209 Wetland<br />

28 Bushkill Swamp<br />

29 LilyPond BrookHeadwaters 30 Pinchot Brook Wetlands<br />

31 Dimmick Meadow Brook Wetlands<br />

32 Buckhorn Oak Barrens<br />

33 Stairway Lake Wetland<br />

34 Milrift Flats<br />

35 Milrift Cliffs<br />

36 MatamorasCliffs 37 Mashipacong Cliffs<br />

38 OldPortJervisRoadShale Barrens<br />

39 Pinchot Falls<br />

40 Sawkill Pond<br />

41 Sawkill Mud Pond<br />

42 Crooked Swamp<br />

43 Shohola Lake<br />

44 Shohola Falls Swamp<br />

45 Wells Road Swamp<br />

46 Taylortown Swamp<br />

47 Shohola Falls West<br />

48 Little MudPond North<br />

49 Smiths Swamp<br />

50 Billings Creek<br />

51 Billings Pond<br />

52 Beaver Lake<br />

53 Lake Giles<br />

54 Blooming Grove Creek<br />

55 White Deer Lake<br />

56 Gates Run Wetland<br />

57 Mainses P ond<br />

58 Fairview Lake<br />

59 Lake Wallenpaupack<br />

60 Route 507Wetland<br />

Bolded sites arenew in the 2011 update<br />

<strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Areas<br />

# SiteName<br />

61 East Branch Wallenpaupack Creek<br />

62 Pine Lake<br />

63 Lake Paupack<br />

64 Promised Land Lake<br />

65 Egypt Meadow Lake<br />

66 Bruce Lake<br />

67 Long Pond Swamp<br />

68 Lake Scott<br />

69 Lake Laura<br />

70 HighKnob<br />

71 Pit Road<br />

72 White BirchSwamp<br />

73 Pecks Pond<br />

74 Maple Swamp<br />

75 Rock Hill Ridge<br />

76 Rock Hill Pond<br />

77 Ben Bush Swamp<br />

78 Dark Swamp<br />

79 Log Tavern Pond<br />

80 Milford Cliffs<br />

81 Raymondskill Falls<br />

82 Dry Brook Shale Barren<br />

83 Adams Creek Ravine<br />

84 Dingmans Falls<br />

85 Fulmer Falls<br />

86 Long Swamp<br />

87 Bald Hill Swamp<br />

88 Sap Swamp<br />

89 Silver Lake<br />

90 Little Bear Swamp<br />

91 Big Bear Swamp<br />

92 Big Bear Swamp Wetland<br />

93 Little Mud Pond<br />

94 Elbow Swamp<br />

95 Painter Swamp<br />

96 Edgemere Road<br />

97 Porters Lake<br />

98 Lake Belle<br />

99 Goose Pond<br />

100 East Mountain<br />

101 Beaver Run Club Pond<br />

102 BigSwamp<br />

103 Twelvemile Pond<br />

104 Lake Minisink<br />

105 Bushkill Road<br />

106 MinksPond<br />

107 Lake Maskenozha and Wetlands<br />

108 Little Bushkill Swamp<br />

109 SunsetLake Woodlands<br />

110 Deckers Creek Ravine<br />

111 Glenside Shale Barren<br />

112 Dickinson Road Bluff<br />

113<br />

Delaware River South of Dingmans<br />

Ferry<br />

114 Stuckey Lake<br />

115 Eschbach Heights Shale Barren<br />

116 Third Pond<br />

117 Second Pond<br />

118 First Pond<br />

119 Sugar Mountain Swamp<br />

120 Shoemakers Barren<br />

121 Bushkill Shale Cliff

Executive Summary<br />

Table 1. <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Areas categorized by significance.<br />

Site Name<br />

Exceptional<br />

Municipality(ies) Description Page<br />

Beaver Lake<br />

Bruce Lake<br />

Delaware River<br />

between Handsome<br />

Eddy and Dingmans<br />

Ferry<br />

Delaware River South<br />

of Dingmans Ferry<br />

Lake Scott<br />

Little Mud Pond North<br />

Little Teedyuskung<br />

Lake<br />

Long Pond Swamp<br />

Blooming Grove<br />

Township<br />

Blooming Grove<br />

Township<br />

Delaware, Dingman,<br />

Milford, Shohola, and<br />

Westfall Townships<br />

Delaware and Lehman<br />

Townships<br />

Blooming Grove<br />

Township<br />

Blooming Grove<br />

Township<br />

Lackawaxen Township<br />

Blooming Grove<br />

Township<br />

Rock Hill Pond Dingman Township<br />

Sawkill Mud Pond<br />

Smiths Swamp<br />

High<br />

Dingman and Milford<br />

Townships<br />

Blooming Grove<br />

Township<br />

Bald Hill Shohola Township<br />

A privately owned glacial lake that supports<br />

nine plant species of concern, three natural<br />

communities of concern, and an additional<br />

species of concern.<br />

This glacial lake is a state forest natural area<br />

that supports nine plant, one butterfly, and four<br />

natural communities of concern.<br />

This section of the Delaware River provides<br />

habitat for three mussel, six dragonfly, four<br />

plant, and two additional species of concern.<br />

A stretch of the Delaware River that supports<br />

populations of three mussel, one moth, four<br />

plant, and one additional species of concern.<br />

This glacial lake complex contains seven plant<br />

and four natural communities of concern.<br />

A glacial lake complex that provides habitat for<br />

seven plants, five insects, and five natural<br />

communities of concern.<br />

Four plants and four natural communities of<br />

concern are found on this privately owned<br />

glacial lake complex.<br />

A state forest natural area that supports five<br />

plants, one butterfly, and three natural<br />

communities of concern on a glacial lake.<br />

Five plant species and three natural<br />

communities of concern were found on this<br />

bog complex.<br />

This privately owned bog complex provides<br />

habitat for five plant species and six natural<br />

communities of concern.<br />

A small, publicly owned bog opening that<br />

contains nine plants, three insects, and two<br />

natural communities of concern.<br />

A natural community of concern that supports<br />

four plant species of concern and an additional<br />

species of concern.<br />

<strong>Pike</strong> County <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Inventory – Executive Summary /<br />

52<br />

52<br />

71, 82,<br />

127,<br />

153,<br />

163<br />

71, 117<br />

53<br />

53<br />

105<br />

54<br />

83<br />

83, 128<br />

55<br />

153<br />

xi

Site Name Municipality(ies) Description Page<br />

Big Bear Swamp Delaware Township<br />

Bushkill Shale Cliff Lehman Township<br />

Bushkill Swamp Shohola Township<br />

Corilla Lake Lackawaxen Township<br />

Crooked Swamp Dingman Township<br />

Delaware River North<br />

of Handsome Eddy<br />

Lackawaxen and<br />

Shohola Townships<br />

East Mountain Greene Township<br />

Forest Lake Lackawaxen Township<br />

Goose Pond Greene Township<br />

Lake Giles<br />

Blooming Grove<br />

Township<br />

Lake Minisink Porter Township<br />

Little Mud Pond Porter Township<br />

Log Tavern Pond Dingman Township<br />

Mashipacong Cliffs Westfall Township<br />

This publicly owned forested wetland supports<br />

a plant and natural community of concern.<br />

A natural community of concern located along<br />

the cliffs of the Delaware River that provides<br />

habitat for a species of concern.<br />

This small bog opening contains a natural<br />

community of concern and supports five plant<br />

and three dragonfly species of concern.<br />

A glacial lake that is a natural community of<br />

concern and provides habitat for four plant<br />

species of concern and one plant species on the<br />

PNHP Watch List.<br />

This degraded bog complex supports four<br />

plants, two insects, and four natural<br />

communities of concern.<br />

A section of the Delaware River that supports<br />

populations of two mussel, six dragonfly, one<br />

plant, and one additional species of concern.<br />

This site is a natural community of concern<br />

that supports one moth and one plant species of<br />

concern.<br />

A privately owned lake that is a natural<br />

community of concern and contains three plant<br />

species of concern and three plant species on<br />

the PNHP Watch List.<br />

This disturbed bog complex provides habitat for<br />

one bird and five plant species of concern, as<br />

well as two species on the PNHP Watch List.<br />

A glacial lake that provides habitat for four<br />

plant species of concern.<br />

A heavily developed lake that supports five<br />

plant species of concern and one plant species<br />

on the PNHP Watch List.<br />

This glacial lake complex supports six plants,<br />

one dragonfly, and three natural communities<br />

of concern, as well as a plant species on the<br />

PNHP Watch List.<br />

This developed lake provides habitat for four<br />

plant species of concern and four plant species<br />

on the PNHP Watch List.<br />

Steep habitat along the Delaware River that is a<br />

natural community of concern and provides<br />

habitat for two species of concern<br />

<strong>Pike</strong> County <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Inventory – Executive Summary / xii<br />

71<br />

117<br />

153<br />

104<br />

82<br />

104,<br />

153<br />

95<br />

104<br />

95<br />

53<br />

143<br />

143<br />

82<br />

163

Site Name Municipality(ies) Description Page<br />

Milford Cliffs Dingman Township<br />

Millrift Cliffs Westfall Township<br />

Millrift Flats Westfall Township<br />

Pecks Pond<br />

Blooming Grove and<br />

Porter Townships<br />

Pine Lake Greene Township<br />

Promised Land Lake<br />

Blooming Grove,<br />

Greene and Palmyra<br />

Townships<br />

Raymondskill Falls Dingman Township<br />

Twelvemile Pond Porter Township<br />

Twin Lakes and<br />

Wetland<br />

White Deer Lake<br />

Shohola Township<br />

Blooming Grove<br />

Township<br />

Wolf Lake Lackawaxen Township<br />

Notable<br />

Adams Creek Ravine Delaware Township<br />

Bald Hill Swamp Porter Township<br />

Steep cliffs along the Delaware River create a<br />

natural community of concern that provides<br />

habitat for a species of concern.<br />

Steep cliffs along the Delaware River that are a<br />

natural community of concern and supports a<br />

plant species of concern and an additional<br />

species of concern.<br />

A natural community of concern that supports<br />

five moth species of concern.<br />

Eight plants, one dragonfly, and one natural<br />

community of concern are found in the<br />

modified glacial lake complex.<br />

This glacial lake provides habitat for 3 plants, 3<br />

insects, and one natural community of concern,<br />

as well as a plant species on the PNHP Watch<br />

List.<br />

A state park with two man-made lakes that<br />

supports seven plant species and three natural<br />

communities of concern.<br />

This waterfall is a geologic feature of concern<br />

that provides habitat for two dragonfly and five<br />

plant species of concern.<br />

This natural community of concern supports<br />

three plant species of concern and one<br />

additional species of concern.<br />

A developed lake and nearby wetlands that<br />

provide habitat for six plant and one dragonfly<br />

species of concern, and well as a plant species<br />

on the PNHP Watch List.<br />

A glacial wetland that contains two natural<br />

communities, three plants, and one additional<br />

species of concern, as well as a plant species on<br />

the PNHP Watch List.<br />

This glacial lake is a natural community of<br />

concern that provides habitat for six plant<br />

species of concern and two plant species on the<br />

PNHP Watch List.<br />

A forested stream that supports populations of<br />

two plant species of concern.<br />

This forested wetland and adjacent stream<br />

corridor contain two natural communities of<br />

concern and one bird species of concern.<br />

<strong>Pike</strong> County <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Inventory – Executive Summary / xiii<br />

83<br />

163<br />

163<br />

54, 144<br />

95<br />

55, 96,<br />

136<br />

83<br />

144<br />

154<br />

56<br />

106<br />

71<br />

143

Site Name Municipality(ies) Description Page<br />

Beaver Run Club Pond Porter Township<br />

Ben Bush Swamp Dingman Township<br />

Big Bear Swamp<br />

Wetland<br />

Delaware Township<br />

Big Swamp Porter Township<br />

Billings Creek<br />

Blooming Grove<br />

Creek<br />

Buckhorn Mountain<br />

Slopes<br />

Buckhorn Oak Barren<br />

Blooming Grove<br />

Township<br />

Blooming Grove<br />

Township<br />

Palmyra Township<br />

Milford and Westfall<br />

Townships<br />

Bushkill Road Porter Township<br />

Dark Swamp Dingman Township<br />

Decker Pond Palmyra Township<br />

Deckers Creek Ravine Lehman Township<br />

Dickinson Road Bluff<br />

Dimmick Meadow<br />

Brook Wetlands<br />

Lehman Township<br />

Milford and Westfall<br />

Townships<br />

Dingmans Falls Delaware Township<br />

Dry Brook Shale<br />

Barren<br />

East Branch<br />

Wallenpaupack Creek<br />

Delaware Township<br />

Greene Township<br />

Edgemere Road Porter Township<br />

A man-made lake that provides habitat for<br />

three plant species of concern.<br />

This palustrine forest is a natural community of<br />

concern.<br />

One plant species of concern was found in this<br />

red spruce dominated palustrine forest.<br />

A forested wetland that provides habitat for a<br />

plant species of concern.<br />

A disturbed stream channel that provides<br />

habitat for a species of concern.<br />

This section of Blooming Grove Creek<br />

supports one bird, one dragonfly, and one plant<br />

species of concern.<br />

A small quarry that provides habitat for a plant<br />

species of concern.<br />

One butterfly species of concern was found in<br />

this barrens habitat that is a natural community<br />

of concern.<br />

This roadside provides habitat for a species of<br />

concern.<br />

One dragonfly and one plant species of concern<br />

were found in this graminoid wetland.<br />

This man-made wetland supports one plant and<br />

five insect species of concern.<br />

One plant species of concern was found in this<br />

forested habitat.<br />

143<br />

<strong>Pike</strong> County <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Inventory – Executive Summary / xiv<br />

82<br />

71<br />

143<br />

52<br />

52<br />

135<br />

127,<br />

163<br />

143<br />

82<br />

135<br />

117<br />

This open habitat supports a species of<br />

117<br />

concern.<br />

Graminoid openings in this wetland contain 127,<br />

one plant and one dragonfly species of concern. 163<br />

This waterfall provides habitat for two plants,<br />

one natural community, and one geologic 71<br />

feature of concern.<br />

A dry, open natural community of concern that<br />

supports a species of concern.<br />

Two dragonfly and two additional species of<br />

concern were found in this section of East<br />

Branch Wallenpaupack Creek.<br />

A species of concern was found in this<br />

roadside habitat.<br />

72<br />

95<br />

143

Site Name Municipality(ies) Description Page<br />

Egypt Meadow Lake<br />

Blooming Grove and<br />

Palmyra Townships<br />

Elbow Swamp Porter Township<br />

Eschbach Heights<br />

Shale Barren<br />

Lehman Township<br />

Fairview Lake Palmyra Township<br />

First Pond Lehman Township<br />

Fourmile Pond<br />

Wetland<br />

Lackawaxen Township<br />

Fulmer Falls Delaware Township<br />

Gates Run Wetland<br />

Blooming Grove<br />

Township<br />

Germantown Swamp Lackawaxen Township<br />

Glenside Shale Barren<br />

High Knob<br />

Lackawaxen River at<br />

Baoba<br />

Lackawaxen River at<br />

Rowland<br />

Delaware and Lehman<br />

Townships<br />

Blooming Grove<br />

Township<br />

Lackawaxen and<br />

Palmyra Townships<br />

Lackawaxen Township<br />

Lake Belle Greene Township<br />

Lake Greeley Lackawaxen Township<br />

This man-made lake provides habitat for three<br />

plants, three dragonflies, and one natural<br />

community of concern.<br />

One plant species of concern was found in this<br />

forested wetland that is a natural community of<br />

concern. A butterfly species of concern was<br />

found along the edge of the wetland.<br />

This habitat supports a population of a species<br />

of concern.<br />

This man-made lake provides habitat for two<br />

plant species of concern and two plant species<br />

on the PNHP Watch List.<br />

A plant species of concern and a plant species<br />

on the PNHP Watch List were found in this<br />

man-made lake.<br />

This wetland provides habitat for a species of<br />

concern.<br />

A waterfall that is a natural community and<br />

geologic feature of concern.<br />

This wetland provides breeding habitat for a<br />

bird species of concern.<br />

This forested wetland is a natural community<br />

of concern.<br />

Steep habitat along the Delaware River that is a<br />

natural community of concern and supports a<br />

species of concern.<br />

An upland forest habitat that supports one plant<br />

species of concern, one natural community of<br />

concern, and an additional species of concern<br />

This section of the Lackawaxen River supports<br />

one dragonfly, three plant, and one additional<br />

species of concern.<br />

The Lackawaxen River in this area provides<br />

habitat for one dragonfly, one plant, and one<br />

additional species of concern.<br />

This glacial lake is a natural community of<br />

concern that supports a plant species of<br />

concern.<br />

One plant species of concern and one plant<br />

species on the PNHP Watch List are located in<br />

this man-made lake.<br />

<strong>Pike</strong> County <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Inventory – Executive Summary /<br />

53, 135<br />

143<br />

117<br />

135<br />

117<br />

104<br />

72<br />

53<br />

104<br />

72, 117<br />

53<br />

104,<br />

135<br />

105<br />

95<br />

105<br />

xv

Site Name Municipality(ies) Description Page<br />

Lake Laura<br />

Lake Maskenozha and<br />

Wetlands<br />

Blooming Grove and<br />

Greene Townships<br />

Delaware and Lehman<br />

Townships<br />

Lake Paupack Greene Township<br />

Lake Wallenpaupack<br />

Lily Pond Brook<br />

Headwaters<br />

Greene and Palmyra<br />

Townships<br />

Milford Township<br />

Little Bear Swamp Delaware Township<br />

Little Bush Kill<br />

Swamp<br />

Long Swamp<br />

Mainses Pond<br />

Maple Swamp<br />

Lehman Township<br />

Delaware and Dingman<br />

Townships<br />

Blooming Grove and<br />

Palmyra Townships<br />

Blooming Grove<br />

Township<br />

Masthope Creek Lackawaxen Township<br />

Matamoras Cliffs Westfall Township<br />

Minks Pond<br />

Old Port Jervis Road<br />

Shale Barrens<br />

Delaware and Lehman<br />

Townships<br />

Westfall Township<br />

Painter Swamp Porter Township<br />

Panther Lake Lackawaxen Township<br />

A privately owned glacial lake that supports<br />

two plant species of concern.<br />

This privately owned man-made lake and<br />

associated wetlands provides habitat for three<br />

plants and one natural community of concern.<br />

Two plant species of concern are found in two<br />

natural communities of concern in this glacial<br />

lake.<br />

This large man-made lake provides habitat for<br />

one bird and one plant species of concern.<br />

A forested wetland and nearby flooded wetland<br />

that support an insect and a plant species of<br />

concern.<br />

This forested wetland provides habitat for a<br />

plant species of concern.<br />

A plant species of concern was found in this<br />

forested wetland.<br />

A privately owned wetland that contains a<br />

plant and natural community of concern.<br />

This man-made lake supports a population of a<br />

plant species of concern, as well as five plant<br />

species on the PNHP Watch List.<br />

A wetland surrounded by development that<br />

provides habitat for three plants, one dragonfly,<br />

and two natural communities of concern.<br />

A stream and associated wetlands that supports<br />

a species of concern.<br />

Steep habitat along the Delaware River that is a<br />

natural community of concern and provides<br />

habitat for a species of concern.<br />

One plant species and one natural community<br />

of concern were found in this man-made lake.<br />

Steep habitat along the Delaware River that is a<br />

natural community of concern and supports a<br />

species of concern.<br />

53, 95<br />

72, 117<br />

<strong>Pike</strong> County <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Inventory – Executive Summary / xvi<br />

95<br />

95, 135<br />

127<br />

72<br />

117<br />

72, 83<br />

54, 135<br />

54<br />

105<br />

163<br />

72, 117<br />

164<br />

This modified bog habitat provides habitat for<br />

one plant and one dragonfly species of concern. 144<br />

A modified glacial lake that supports a plant<br />

species of concern.<br />

105

Site Name Municipality(ies) Description Page<br />

Pinchot Brook<br />

Wetlands<br />

Pinchot Falls<br />

Milford Township<br />

Dingman and Milford<br />

Townships<br />

Pit Road Porter Township<br />

Point Peter Lackawaxen Township<br />

Porters Lake Porter Township<br />

Rock Hill Ridge<br />

Blooming Grove and<br />

Dingman Townships<br />

Route 507 Wetland Greene Township<br />

Sap Swamp<br />

Delaware and Porter<br />

Townships<br />

Sawkill Pond Dingman Township<br />

Second Pond Lehman Township<br />

Shoemakers Barren Lehman Township<br />

Shohola Falls Shohola Township<br />

Shohola Falls Swamp Shohola Township<br />

Shohola Falls West<br />

Shohola Lake<br />

Blooming Grove<br />

Township<br />

Blooming Grove,<br />

Dingman, and Shohola<br />

Townships<br />

Silver Lake Delaware Township<br />

A beaver modified wetland that supports three<br />

insect and one plant species of concern.<br />

This waterfall is a natural community and<br />

geologic feature of concern.<br />

Roadside habitat that supports a plant species<br />

of concern.<br />

This natural community of concern provides<br />

habitat for a species of concern.<br />

Two man-made lakes that provide habitat for<br />

three plant species of concern and an additional<br />

species of concern.<br />

This dry forest habitat provides habitat for two<br />

plant species of concern.<br />

One bird and one plant species of concern were<br />

found in this beaver modified wetland.<br />

A graminoid dominated, beaver modified<br />

wetland that supports a dragonfly species of<br />

concern.<br />

This man-made lake provides habitat for a<br />

species of concern.<br />

A privately owned lake that supports three<br />

plant species of concern and one plant on the<br />

PNHP Watch List.<br />

Two natural communities of concern that<br />

provide habitat for a species of concern.<br />

This waterfall is a geologic feature of concern.<br />

A small nearby wetland supports a plant<br />

species of concern.<br />

A forested wetland that is a natural community<br />

of concern.<br />

This upland habitat supports a population of a<br />

plant species of concern.<br />

A man-made lake that provides habitat for one<br />

bird, three plant, and one additional species of<br />

concern.<br />

Two plant species of concern were found in<br />

this man-made lake.<br />

127<br />

83, 127<br />

144<br />

105<br />

144<br />

<strong>Pike</strong> County <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Inventory – Executive Summary / xvii<br />

83<br />

96<br />

72, 144<br />

84<br />

118<br />

118<br />

154<br />

154<br />

55<br />

55, 84,<br />

154<br />

72

Site Name Municipality(ies) Description Page<br />

Spring Brook Wetland<br />

Stairway Lake<br />

Wetland<br />

State Game Lands<br />

#209 Wetland<br />

State Game Lands<br />

#316 Slopes<br />

Blooming Grove and<br />

Lackawaxen Townships<br />

Westfall Township<br />

Shohola Township<br />

Lackawaxen Township<br />

Stuckey Lake Lehman Township<br />

Sugar Mountain<br />

Swamp<br />

Sunset Lake<br />

Woodlands<br />

Taylortown Swamp<br />

Lehman Township<br />

Lehman Township<br />

Blooming Grove<br />

Township<br />

Teedyuskung Lake Lackawaxen Township<br />

Third Pond Lehman Township<br />

Tinkwig Creek<br />

Roadside<br />

Lackawaxen Township<br />

Welcome Lake Lackawaxen Township<br />

Well Road Swamp<br />

Blooming Grove<br />

Township<br />

Westcolang Pond Lackawaxen Township<br />

White Birch Swamp<br />

Local<br />

Billings Pond<br />

Blooming Grove and<br />

Porter Townships<br />

Blooming Grove<br />

Township<br />

Walker Lake Shohola Township<br />

A wetland that provides breeding habitat for a<br />

bird species of concern.<br />

This forested wetland is a natural community<br />

of concern that provides habitat for a plant<br />

species of concern.<br />

A graminoid dominated wetland that supports a<br />

plant species of concern.<br />

This small grassland opening in the<br />

surrounding forest provides habitat for a plant<br />

species of concern.<br />

A man-made lake that supports a plant species<br />

of concern.<br />

This small headwaters wetland contains a<br />

population of a plant species of concern.<br />

Woodlands that support a population of a moth<br />

species of concern.<br />

This forested wetland is a natural community<br />

of concern.<br />

Two plant species of concern were found in<br />

this privately owned lake.<br />

A degraded wetland that supports a plant<br />

species of concern and a plant species on the<br />

PNHP Watch List.<br />

Roadside habitat that supports a small<br />

population of a species of concern.<br />

Two plant species of concern were found in<br />

this glacial lake that is a natural community of<br />

concern.<br />

This forested wetland contains a plant and a<br />

natural community of concern.<br />

A man-made lake that supports three plant<br />

species of concern.<br />

This forested wetland is a natural community<br />

of concern.<br />

A beaver flooded wetland that provides habitat<br />

for a plant species on the PNHP Watch List.<br />

One plant species on the PNHP Watch List was<br />

found at this man-made lake.<br />

55, 105<br />

164<br />

154<br />

105<br />

118<br />

118<br />

118<br />

<strong>Pike</strong> County <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Inventory – Executive Summary / xviii<br />

55<br />

105<br />

118<br />

105<br />

105<br />

55<br />

105<br />

56, 144<br />

52<br />

154

INTRODUCTION<br />

Our natural environment is key to human health and sustenance. A healthy environment provides clean air<br />

and water; supports fish, game and agriculture; and furnishes renewable sources of materials for countless<br />

aspects of our livelihoods and economy. In addition to these direct services, a clean and healthy<br />

environment plays a central role in our quality of life, whether through its aesthetic value (found in forested<br />

ridges, mountain streams and encounters with wildlife), or in the opportunities it provides for exploration,<br />

recreation, and education. Finally, a healthy natural environment supports economic growth by adding to the<br />

region’s attractiveness as a location for new business enterprises, and provides the basis for the recreation,<br />

tourism, and forestry industries--all of which have the potential for long-term sustainability. Fully functional<br />

ecosystems are the key indicators of a healthy environment and working to maintain ecosystems is essential<br />

to the long-term sustainability of our economies.<br />

An ecosystem is “the complex of interconnected living organisms inhabiting a particular area or unit of<br />

space, together with their environment and all their interrelationships and relationships with the<br />

environment” (Ostroumov 2002). All the parts of an ecosystem are interconnected--the survival of any<br />

species or the continuation of a given natural process depends upon the system as a whole, and in turn,<br />

these species and processes contribute to maintaining the system. An important consideration in assessing<br />

ecosystem health is the concept of biodiversity. Biodiversity can be defined as the full variety of life that<br />

occurs in a given place, and is measured at several scales: genetic diversity, species, natural communities,<br />

and landscapes.<br />

Diversity typically allows species or communities to adapt successfully to environmental changes or<br />

disease. Genetic diversity, for example, refers to the variation in genetic makeup between individuals and<br />

populations of organisms. Though sugar maple (Acer saccharum) may be found in many areas of<br />

<strong>Pennsylvania</strong>, those in <strong>Pike</strong> County likely have a different genetic makeup than those in Philadelphia<br />

County; this allows these trees to survive in the unique conditions in which they grow. In order to<br />

conserve genetic diversity, plants native to an area from local genetic stock should be used as much as<br />

possible in both private and public plantings in <strong>Pike</strong> County. It is also important to maintain natural<br />

patterns of gene flow; this is made possible through the preservation of migration paths and corridors<br />

across the landscape, and through encouraging the dispersal of pollen and seeds among populations<br />

(Thorne et al., 1996). Furthermore, declines in native species diversity can alter ecosystem processes such<br />

as nutrient cycling, decomposition, and plant productivity (Naeem et al., 1999, Randall, 2000). Because<br />

of the interdependent nature of our natural systems, including those we directly depend on for our<br />

livelihood and quality of life, it is essential to conserve native biodiversity at all scales (genes, species,<br />

natural communities, and landscapes) if ecosystems are to continue functioning.<br />

From an ecological perspective, a landscape is “a large area of land that includes a mosaic of natural<br />

community types and a variety of habitats for many species” (Massachusetts Biomap, 2000). A natural<br />

community is “an interacting assemblage of organisms, their physical environment, and the natural<br />

processes that affect them” (Thompson and Sorenson, 2000). <strong>Natural</strong> communities are usually defined by<br />

their dominant plant species or the geological features on which they depend; <strong>Pike</strong> County examples include<br />

red spruce palustrine forest, and leatherleaf – bog-rosemary peatland. Each type of natural community<br />

represents habitat for a different group of species, hence identification and stewardship of the full range of<br />

native community types is needed to meet the challenge of conserving habitat for all species. Classifying<br />

these communities gives ecologists, planners, managers, and landowners a common language with which to<br />

discuss land conservation. At the landscape scale, it is important to consider whether communities and<br />

habitats are isolated or connected. It is important to maintain corridors of natural landscape traversable by<br />

wildlife, and to preserve natural areas large enough to support viable populations and ecosystems.<br />

<strong>Pennsylvania</strong>’s natural heritage is rich in biodiversity and the Commonwealth includes many examples of<br />

high quality natural communities and large expanses of natural landscapes. The extensive tracts of forest<br />

in the northern and central parts of the state represent a large portion of the remaining areas of suitable<br />

<strong>Pike</strong> County <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Inventory – Introduction / 1

habitat in the mid-Atlantic region for many forest-dependent species of birds and mammals.<br />

Unfortunately, biodiversity and ecosystem health are seriously threatened in many parts of the state by<br />

pollution and habitat loss. The <strong>Pennsylvania</strong> Biological Survey reports that approximately 25,000 species<br />

are thought to occur in the state (http://www.altoona.psu.edu/pabs/boxscore.html). Of all the animals and<br />

vascular plants that have been documented in the state, more than one in ten are imperiled; 156 have been<br />

lost entirely since European settlement and 351 are threatened or endangered (PA 21 st Century<br />

Environment Commission 1998). Many of these species are imperiled because available habitat has been<br />

reduced and/or degraded.<br />

Fifty-six percent of <strong>Pennsylvania</strong>’s wetlands have been lost or substantially degraded by filling, draining,<br />

or conversion to ponds (Dahl 1990). According to the <strong>Pennsylvania</strong> Department of Environmental<br />

Protection (DEP), sixty percent of those <strong>Pennsylvania</strong> lakes that have thus far been assessed for biological<br />

health are listed as impaired. Of 85,000 miles of stream in <strong>Pennsylvania</strong>, 84,867 miles have been assessed<br />

for water quality. From this assessment, nearly 15,583 miles have been designated as impaired due to<br />

abandoned mine discharges, acid precipitation, and agricultural and urban runoff (PA DEP 2010). The<br />

species that depend on these habitats are correspondingly under threat: 58 percent of threatened or<br />

endangered plant species are wetland or aquatic species; 13 percent of <strong>Pennsylvania</strong>’s 200 native fish<br />

species have been lost, while an additional 23 percent are imperiled. Among freshwater mussels, one of<br />

the most globally imperiled groups of organisms, 18 of <strong>Pennsylvania</strong>’s 67 native species are extirpated<br />

(meaning locally extinct) and another 22 are imperiled (Goodrich et al. 2003).<br />

Prior to European settlement, over ninety percent of <strong>Pennsylvania</strong>’s land area was forested. Today, sixty<br />

percent of the state is still forested, but much of this forest is fragmented by roads, utility rights-of-way,<br />

agriculture, and development. Only 42 percent is interior forest habitat, meaning that some of the species<br />

that depend upon interior forest habitat are in decline (Goodrich et al. 2003). In addition to habitat<br />

fragmentation, forest pests, acid precipitation (which causes nutrient leaching and stunted growth), over<br />

browsing by deer, and invasive species also threaten forest ecosystem health.<br />

The <strong>Pennsylvania</strong> <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> <strong>Program</strong> (PNHP) assesses the conservation status of species of<br />

vascular plants, vertebrates, and a few of the invertebrate species native to <strong>Pennsylvania</strong>. While<br />

<strong>Pennsylvania</strong> hosts a diversity of other life forms, such as mosses, lichens and fungi, too little information<br />

is known of these species to assess their conservation status at this time. Without information about all<br />

species, it is possible to protect at least some rare species by conserving rare natural communities. Species<br />

tend to occur in specific habitats or natural communities, and by conserving examples of all natural<br />

community types, we will also conserve many of the associated species, whether or not we even know<br />

what those species are. Thus, the natural community approach is a coarse filter for biodiversity protection,<br />

but PNHP uses the fine filter of individual species identification for those species for which it is feasible.<br />

The goals of this report are to identify areas important in sustaining biodiversity at the species, natural<br />

community, and landscape levels and to provide that information to better inform land use decisions.<br />

County <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Inventories (<strong>CNHI</strong>s) identify areas in the state that support <strong>Pennsylvania</strong>’s rare,<br />

threatened, or endangered species as well as natural communities that are considered to be rare in the state<br />

or exceptional examples of the more common community types. The areas that support these features are<br />

identified as <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Areas.<br />

A description of each area’s natural features and recommendations for maintaining their viability are<br />

provided for each <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Area. Also, in an effort to provide information focused on planning<br />

for biodiversity conservation, this report includes species and natural community fact sheets, references<br />

and links to information on invasive exotic species, and information from other conservation planning<br />

efforts such as the <strong>Pennsylvania</strong> Audubon’s Important Bird Area project. Together with the other land use<br />

information, this report can help guide the planning and land management necessary to maintain the<br />

ecosystems on which our natural heritage depends.<br />

<strong>Pike</strong> County <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Inventory – Introduction / 2

COUNTY OVERVIEW<br />

<strong>Pike</strong> County is located in eastern <strong>Pennsylvania</strong>.<br />

It is bordered by Wayne County to the<br />

northwest, Monroe County to the southwest,<br />

Sussex County, New Jersey to the southeast,<br />

Orange County, New York to the east and<br />

Sullivan County, New York to the north. The<br />

county has a total area of 567 mi² (1,469 km²).<br />

<strong>Pike</strong> County is composed of 11 townships and<br />

2 boroughs. According to estimates by the U.S.<br />

Census Bureau in 2006, <strong>Pike</strong> County was the<br />

fastest growing county in <strong>Pennsylvania</strong>. In<br />

2010, the population was estimated at 57,369<br />

with a population density of approximately 85<br />

people per square mile (133 people/km 2 ).<br />

<strong>Pike</strong> County was created in 1814 from a<br />

section of Wayne County; and in 1836 a<br />

portion of <strong>Pike</strong> County was used to form<br />

Monroe County. The borough of Milford is the<br />

county seat.<br />

The existing land use patterns within the<br />

county are influenced and shaped by the<br />

region’s natural features. Over three-fourths of<br />

the land throughout the county is forested;<br />

wetlands cover 7%, streams and lakes 4%,<br />

residential areas 4%, and agriculture only 3%.<br />

Thirty-four percent of <strong>Pike</strong> County is managed<br />

public lands; conservancies have protected three<br />

percent and the other 63% is private land (Table<br />

2).<br />

Figure 1. Townships and boroughs of <strong>Pike</strong> County. Major<br />

roads are shown on this map as well.<br />

Ownership Area<br />

(acres)<br />

% area<br />

Public land 124,969 34 %<br />

Other conservation land 10,597 3 %<br />

Private / unknown ownership 227,426 63%<br />

Total 362,992<br />

Table 2. Ownership breakdown of land within <strong>Pike</strong><br />

County as of 2010. Figures are approximate and based<br />

upon best available data.<br />

<strong>Pike</strong> County <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Inventory – County Overview / 3

OVERVIEW OF THE NATURAL FEATURES OF PIKE COUNTY<br />

The natural landscape is best described as a series of ecosystemsgroups of interacting living organisms and<br />

the physical environment that they inhabit. Climate, topography, geology, and soils play an important role<br />

in the development of ecosystems (forests, fields, and wetlands) and physical features (streams, rivers and<br />

mountains) that occur across the landscape. Disturbances, both natural and human induced, have been<br />

influential in forming and altering many of <strong>Pike</strong> County’s ecosystems, causing local extinction of some<br />

species and the introduction of others. These combined factors provide the framework for conducting a<br />

County <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Inventory, which locates and identifies exemplary natural communities and<br />

species of concern in the county. The following sections provide a brief overview of the geology, soils,<br />

surface water, and vegetation of <strong>Pike</strong> County.<br />

Figure 2. Bedrock Geology of <strong>Pike</strong> County. Much of the county is underlain by Devonian Age sandstone, siltstone,<br />

mudstone, shale, and conglomerate.<br />

<strong>Pike</strong> County <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Inventory – <strong>Natural</strong> History Overview / 4

Physiography and Geology<br />

Most of <strong>Pike</strong> County lies within the Glaciated Low Plateau Section of the Appalachian Plateaus Province.<br />

The western end of the county is in the glaciated Pocono Plateau section of the same province. The<br />

Appalachian Plateau Province is characterized by horizontal layers of rock cut by many stream valleys. <strong>Pike</strong><br />

County is underlain by bedrock from the Devonian period. The bedrock is composed of sandstone, siltstone,<br />

mudstone, shale, and conglomerate. All of <strong>Pike</strong> County has been influenced by glaciation – most recently by<br />

the Wisconsin Glacier that withdrew about 10,000 to 15,000 years ago (Larsen 1982). Glaciation modified the<br />

landscape by carving valleys, scraping mountains, leaving depressions that filled with water, and leaving<br />

deposits of rock, sand, silt, and clay as unstratified glacial till and stratified drift. Glacial debris brought from<br />

other areas produced soil types that could not have developed from the bedrock in the county. New drainage<br />

patterns that developed due to the scraping and deposition of debris and ice resulted in the formation of the<br />

many wetlands and natural ponds in the county. Many of the plant species that were common during and<br />

shortly after the glacial period retreated northward as the climate warmed. Some of these species can still be<br />

found in the bogs and other wetland habitats that are found in the county.<br />

Figure 3. Generalized soil associations of <strong>Pike</strong> County.<br />

Soils<br />

Soil patterns in <strong>Pike</strong> County reflect either the bedrock beneath the soils or the glacial material that was deposited<br />

over the landscape. The soils that developed have influenced the vegetation, settlement and land use patterns<br />

within the county. The seven soil associations recognized within the county are shown in Figure 3. A description<br />

of soils associations, along with their abundance and land use within <strong>Pike</strong> County, is found in Table 3.<br />

<strong>Pike</strong> County <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> Inventory – <strong>Natural</strong> History Overview / 5

Table 3. Soil associations described for <strong>Pike</strong> County, adapted from The Soil Association of <strong>Pike</strong> County<br />

(USDA, 1969).<br />

Soil<br />

Association<br />

Description<br />

Percentage<br />

of Area in<br />

County<br />

Land Use<br />

Moderately deep to very deep; course loamy and fine<br />

Found in floodplains along the<br />

Chenango-<br />

Pope-Holly<br />

loamy; somewhat poorly drained to well drained soils;<br />

found on glacial uplands; derived from sandstone,<br />

siltstone, and shale; formed in glacial and heavy-<br />

12<br />

Delaware and Lackawaxen<br />

Rivers, much of this association<br />

has been cleared for pasture and<br />

loamy till.<br />

row crops.<br />

Hazelton-<br />

DeKalb-<br />

Buchanan<br />

Deep; loamy-skeletal and fine-loamy; moderately well<br />

drained to well drained soils; found on low hills,<br />

ridges, and convex hillsides; derived from sandstone,<br />

siltstone, and shale; formed in residuum or glacial till.<br />

22<br />

Located above the bluffs of the<br />

Delaware River, most of this<br />

association is wooded.<br />

Lackawanna-<br />

Arnot-<br />

Morris<br />

Shallow to very deep; coarse-loamy and loamyskeletal,<br />

somewhat poorly drained to somewhat<br />

excessively drained soils; found on glaciated uplands;<br />

derived from sandstone, siltstone, and shale, formed in<br />

glacial till.<br />

Very deep; somewhat poorly drained to moderately<br />

1<br />

Very little of this association<br />

occurs in the county, but is<br />

mainly forested with bedrock<br />

outcrops.<br />

Mardin-<br />

Histosols-<br />

Volusia<br />

well drained soils; found on uniform slopes, sides and<br />

divides, plateaus, convex dissected glacial uplands,<br />

and bogs; derived from basal till, siltstone, sandstone,<br />