Linnaeus was right all along: Ulva and Enteromorpha are not distinct ...

Linnaeus was right all along: Ulva and Enteromorpha are not distinct ...

Linnaeus was right all along: Ulva and Enteromorpha are not distinct ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Eur. J. Phycol. (August 2003), 38: 277 – 294.<br />

<strong>Linnaeus</strong> <strong>was</strong> <strong>right</strong> <strong>all</strong> <strong>along</strong>: <strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> <strong>are</strong> <strong>not</strong><br />

<strong>distinct</strong> genera<br />

HILLARY S. HAYDEN 1 , JAANIKA BLOMSTER 2 *, CHRISTINE A. MAGGS 2 ,<br />

PAUL C. SILVA 3 , MICHAEL J. STANHOPE 2# AND J. ROBERT WAALAND 1<br />

1Department of Botany, Box 355325, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98195-5325, USA<br />

2School of Biology <strong>and</strong> Biochemistry, Queen’s University, Medical Biology Centre, 97 Lisburn Road, Belfast, BT9 7BL,<br />

Northern Irel<strong>and</strong>, UK<br />

3University Herbarium, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720-2465, USA<br />

(Received 25 June 2002; accepted 16 May 2003)<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong>, one of the first Linnaean genera, <strong>was</strong> later circumscribed to consist of green seaweeds with distromatic blades, <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> Link <strong>was</strong> established for tubular forms. Although several lines of evidence suggest that these generic<br />

constructs <strong>are</strong> artificial, <strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> have been maintained as separate genera. Our aims were to determine<br />

phylogenetic relationships among taxa currently attributed to <strong>Ulva</strong>, <strong>Enteromorpha</strong>, Umbraulva Bae et I.K. Lee <strong>and</strong> the<br />

mo<strong>not</strong>ypic genus Chloropelta C.E. Tanner, <strong>and</strong> to make any nomenclatural changes justified by our findings. Analyses of<br />

nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer DNA (ITS nrDNA) (29 ingroup taxa including the type species of <strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong>), the chloroplast-encoded rbcL gene (for a subset of taxa) <strong>and</strong> a combined data set were carried out. All trees<br />

had a strongly supported clade consisting of <strong>all</strong> <strong>Ulva</strong>, <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> <strong>and</strong> Chloropelta species, but <strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong><br />

were <strong>not</strong> monophyletic. The recent removal of Umbraulva olivascens (P.J.L. Dangeard) Bae et I.K. Lee from <strong>Ulva</strong> is<br />

supported, although the relationship of the segregate genus Umbraulva to <strong>Ulva</strong>ria requires further investigation. These<br />

results, combined with earlier molecular <strong>and</strong> culture data, provide strong evidence that <strong>Ulva</strong>, <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> <strong>and</strong> Chloropelta<br />

<strong>are</strong> <strong>not</strong> <strong>distinct</strong> evolutionary entities <strong>and</strong> should <strong>not</strong> be recognized as separate genera. A comparison of traits for surveyed<br />

species revealed few synapomorphies. Because <strong>Ulva</strong> is the oldest name, <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> <strong>and</strong> Chloropelta <strong>are</strong> here reduced to<br />

synonymy with <strong>Ulva</strong>, <strong>and</strong> new combinations <strong>are</strong> made where necessary.<br />

Key words: Chloropelta, <strong>Enteromorpha</strong>, nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer DNA (ITS nrDNA), rbcL, <strong>Ulva</strong>,<br />

Umbraulva<br />

Introduction<br />

‘<strong>Ulva</strong> is distinguished from <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> on the<br />

basis of its distromatic blade, which in certain<br />

species (e.g. <strong>Ulva</strong> linza) may become tubular at<br />

the margins <strong>and</strong> thus approach the situation in<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> wherein at least the adult th<strong>all</strong>i <strong>are</strong><br />

markedly tubular <strong>and</strong> hence monostromatic.<br />

This criterion is sometimes difficult to apply,<br />

<strong>and</strong> opinion is divided as to whether such species<br />

as U. linza should be referred to <strong>Ulva</strong> or<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong>. There is perhaps something to<br />

be said in favor of those early workers who<br />

treated <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> as a section of <strong>Ulva</strong>.’<br />

(Silva, 1952)<br />

Correspondence to: H. Hayden. e-mail: hhayden@u.<strong>was</strong>hington.edu<br />

*Present address: Division of Systematic Biology, PO Box 7,<br />

University of Helsinki, 00014 Helsinki, Finl<strong>and</strong>.<br />

# Present address: Bioinformatics, GlaxoSmithKline, 1250<br />

S. Collegeville Road, Collegeville, PA 19426, USA.<br />

ISSN 0967-0262 print/ISSN 1469-4433 online # 2003 British Phycological Society<br />

DOI: 10.1080/1364253031000136321<br />

‘A given swarmer population [of U. lactuca] may<br />

produce <strong>all</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong>-like plants, <strong>all</strong> distromatic<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong> plants, a mixture of both types, or<br />

plants displaying both morphologies on the same<br />

plant.’<br />

(Bonneau, 1977)<br />

‘The similarity of the abnormal filamentous<br />

uniseriate growth of <strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> the fact that even with bacterial reinfection<br />

the <strong>Ulva</strong>-58 [isolate] produces at best th<strong>all</strong>i<br />

similar to <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> support the conclusion<br />

of Bonneau (1977) that there <strong>are</strong> at present no<br />

valid criteria for the maintenance of <strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> as separate genera.’<br />

(Provasoli & Pintner, 1980)<br />

Despite evidence to the contrary, the cosmopolitan<br />

algal genera <strong>Ulva</strong> L. <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> Link have<br />

been maintained to the present day (e.g. Gabrielson<br />

et al., 2000; Graham & Wilcox, 2000). The

H. S. Hayden et al.<br />

separation is convenient, because the majority of<br />

currently recognized species can be readily assigned<br />

to one genus or the other on the basis of<br />

morphology. The genus <strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>was</strong> one of the first<br />

named by <strong>Linnaeus</strong> (1753) <strong>and</strong> initi<strong>all</strong>y included a<br />

variety of unrelated algae. In the nineteenth<br />

century its members were split into several genera.<br />

Green seaweeds with distromatic blades were<br />

maintained in <strong>Ulva</strong>, <strong>and</strong> tubular green seaweeds<br />

were moved to <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> (Link, 1820). Papenfuss<br />

(1960) argued that <strong>Linnaeus</strong> based his<br />

diagnosis of <strong>Ulva</strong> on <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> intestinalis<br />

(the type species of <strong>Enteromorpha</strong>) so that the<br />

names <strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> should both be<br />

typified by E. intestinalis, but the type of <strong>Ulva</strong> is<br />

now conserved with <strong>Ulva</strong> lactuca L. (Greuter et al.,<br />

2000). Of the more than 140 <strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> 135<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> species described worldwide (Index<br />

Nominum Algarum, 2002), approximately 50 <strong>Ulva</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> 35 <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> species <strong>are</strong> currently recognized<br />

(Guiry & NicDonncha, 2002).<br />

Several lines of evidence suggest that these<br />

generic constructs <strong>are</strong> artificial. Species exist in<br />

nature that have intermediate forms, such as E.<br />

linza with an <strong>Enteromorpha</strong>-like tubular base <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Ulva</strong>-like distromatic blade dist<strong>all</strong>y, <strong>and</strong> several<br />

culture studies have revealed flexibility between<br />

tubular <strong>and</strong> blade morphologies. Gayral (1959,<br />

1967) reported the development of tubular, or<br />

parti<strong>all</strong>y tubular, th<strong>all</strong>i in cultures of some <strong>Ulva</strong><br />

species. Bonneau (1977) observed clonal progeny of<br />

U. lactuca with distromatic, parti<strong>all</strong>y distromatic or<br />

completely tubular blades, as well as individuals<br />

that were completely distromatic in one <strong>are</strong>a of the<br />

blade <strong>and</strong> tubular in a<strong>not</strong>her. Føyn (1960, 1961)<br />

produced stable phe<strong>not</strong>ypic mutants of U. mutabilis<br />

with tubular fronds that were capable of<br />

successful mating with wild-type individuals. Addition<strong>all</strong>y,<br />

axenic culture experiments have revealed<br />

similarities that span generic boundaries. In the<br />

absence of native bacteria, <strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong><br />

cultures displayed similar abnormal morphologies<br />

(Provasoli, 1965; Berglund, 1969; Kapraun, 1970;<br />

Fries, 1975; Provasoli & Pintner, 1980).<br />

Most molecular phylogenies corroborate results<br />

from culture experiments. Four studies that include<br />

more than one or two representatives of each genus<br />

have been published (Blomster et al., 1999; Tan et<br />

al., 1999; Woolcott & King, 1999; Malta et al.,<br />

1999). Among these, Tan et al. (1999) is the most<br />

extensive with 21 <strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> species<br />

sampled primarily from Europe. Based on nuclear<br />

ribosomal internal transcribed spacer DNA (ITS<br />

nrDNA) trees, the authors proposed that <strong>Enteromorpha</strong><br />

be collapsed into <strong>Ulva</strong>. Other ITS nrDNA<br />

studies of European taxa (Blomster et al., 1999;<br />

Malta et al., 1999) supported their findings.<br />

However, preliminary results for taxa from eastern<br />

Australia based on the more conserved plastidencoded<br />

RUBISCO large subunit gene (rbcL)<br />

supported separation of the two genera (Woolcott<br />

& King, 1999).<br />

The aims of the present study were to determine<br />

the phylogenetic relationships of taxa currently<br />

attributed to <strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> <strong>and</strong> to make<br />

any nomenclatural changes justified by our findings.<br />

To do this, we included the type species of<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong>, <strong>and</strong> sampled from a broad<br />

geographical <strong>are</strong>a. We also sampled two species<br />

formerly included in <strong>Ulva</strong> – Umbraulva olivascens<br />

(P.J.L. Dangeard) Bae et I.K. Lee <strong>and</strong> Chloropelta<br />

caespitosa C.E. Tanner – to investigate their<br />

relationship to <strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> taxa. We<br />

obtained sequences of ITS nrDNA for <strong>all</strong> 29<br />

ingroup taxa; the chloroplast-encoded rbcL gene<br />

<strong>was</strong> sequenced for a subset of taxa, for which<br />

combined analyses were also carried out.<br />

Materials <strong>and</strong> methods<br />

278<br />

Northeast Pacific collections (Table 1) were isolated into<br />

culture when possible. Unialgal cultures were grown in<br />

Guillard’s f/2 enriched seawater at 158C in glass culture<br />

vessels under 30 – 50 mmol m 72 s 71 in a 16 h light:8 h<br />

dark photoregime. <strong>Ulva</strong> collections from Australia,<br />

Chile, Hawaii, Spain <strong>and</strong> Japan were received as silicagel-preserved<br />

specimens. Vouchers for collections were<br />

deposited in the University of Washington Herbarium<br />

(WTU). Herbarium studies of type <strong>and</strong> other relevant<br />

material were carried out in the Natural History<br />

Museum London (BM) <strong>and</strong> the Dillenian Herbarium,<br />

Oxford University (OXF). All herbarium abbreviations<br />

<strong>are</strong> as listed in the Index Herbariorum (http://www.nybg.org/bsci/ih/ih.html).<br />

One Chloropelta, one Umbraulva, 17 <strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> 10<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> accessions were included in ITS nrDNA<br />

analyses. rbcL sequences were available only from algal<br />

samples collected by the present authors, with the<br />

exception of <strong>Ulva</strong> rigida for which amplification difficulties<br />

were experienced. Thus, a subset of one Chloropelta,<br />

one Umbraulva, 12 <strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> seven <strong>Enteromorpha</strong><br />

samples were included in rbcL analyses (Table 1). Taxa<br />

were chosen for outgroup comparison on the basis of<br />

prior molecular analyses of generic relationships in the<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong>les (Hayden & Waal<strong>and</strong>, 2002). In each case the<br />

type species of the genus <strong>was</strong> studied, as follows (with<br />

approximate number of species in each genus <strong>not</strong>ed in<br />

p<strong>are</strong>ntheses): Blidingia minima var. minima (5), Kornmannia<br />

leptoderma (1), Percursaria percursa (2) <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Ulva</strong>ria obscura var. blyttii (2). All outgroups were used<br />

in the rbcL analysis, but B. minima var. minima <strong>and</strong> K.<br />

leptoderma were excluded from ITS nrDNA analyses<br />

because large sections of the spacers in these taxa were<br />

unalignable with ingroup taxa.<br />

DNA extraction from silica-gel-preserved specimens<br />

<strong>was</strong> preceded by a rehydration step in which 14 – 18 mg<br />

of material <strong>was</strong> rehydrated in 200 ml of double-distilled,<br />

UV-treated water at 48C for 10 min. Total DNA <strong>was</strong><br />

extracted from fresh cultured or rehydrated material

<strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> <strong>are</strong> <strong>not</strong> <strong>distinct</strong> genera<br />

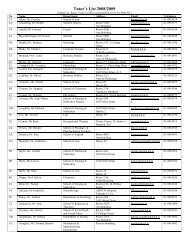

Table 1. Details of the sampled taxa<br />

Taxon Collection information or ITS rDNA sequence origin<br />

using a modified CTAB method (Doyle & Doyle, 1990;<br />

Hughey et al., 2001). rbcL sequences of eight European<br />

taxa were obtained from genomic DNA previously used<br />

for ITS nrDNA sequences published elsewhere (Table 1).<br />

Total genomic DNA (10 – 20 ng) <strong>was</strong> added to six<br />

25 ml PCR reactions each containing final concentrations<br />

of 1 6 PCR Buffer II (PE Applied Biosystems), 1.5 mM<br />

MgCl 2, 0.8 mM dNTPs (GibcoBRL), 0.3 U AmpliTaq<br />

DNA Polymerase (PE Applied Biosystems) <strong>and</strong> 0.8 mM<br />

of each primer. ITS nrDNA reactions also contained 5%<br />

DMSO (Sigma). Six reactions were performed in order<br />

to produce more product <strong>and</strong> to avoid sequence errors<br />

resulting from PCR amplification. PCR amplification<br />

ITS<br />

rDNA rbcL<br />

Chloropelta caespitosa C.E. Tanner Kobe, Hyogo Pref., Japan. 22 Mar 2000. Coll. H.<br />

Kawai<br />

AY260556 AY255858<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> clathrata (Roth) Greville Blomster et al. 1999 (as E. muscoides) AF127170 AY255862<br />

E. compressa (L.) Nees Blomster et al. 1998 AF035350 AY255859<br />

E. flexuosa (Wulfen) J. Agardh Leskinen & Pamilo 1997 AJ234306 na<br />

E. intestinalis (L.) Nees Blomster et al. 1998 AF035342 AY255860<br />

E. intestinaloides Koeman et van den Hoek Tan et al. 1999 AJ234303 na<br />

E. linza (L.) J. Agardh Humboldt Bay, CA USA, 19 Jun 2000. Coll. H.S.<br />

Hayden & F. Shaunessey<br />

AY260557 AY255861<br />

E. procera Ahlner Coll. J. Blomster AY260558 AY255863<br />

E. prolifera (O.F. Mu¨ ller.) J. Agardh Tan et al. 1999 AJ234304 AY255864<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> sp. I Bodega Bay, CA, USA. 17 Jun 2000. Coll. H.S. Hayden AY260559 AY255865<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> sp. II Tan et al. 1999 AJ234308 na<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong> armoricana Dion, de Reviers et Coat Coat et al. 1998 na na<br />

U. australis Areschoug Woolcott & King 1999 AF099726 na<br />

U. californica Wille in Collins, Holden et Setchell La Jolla, CA, USA. 14 Jun 1999. Coll. H.S. Hayden AY260560 AY255866<br />

U. fasciata Delile Kihei, Maui, USA. 6 Feb 2000. Coll. L. Hodgson AY260561 AY255867<br />

U. fenestrata Postels et Ruprecht San Juan Is., WA, USA. 15 Jun 1998. Coll. H.S.<br />

Hayden & D.J. Garbary, MA715<br />

AY260562 AF499668<br />

U. lactuca L. Tan et al. 1999 AJ234310 AF499669<br />

U. lobata (Kützing) Setchell et Gardner Newport, OR, USA. 16 May 1999. Coll. H.S. Hayden<br />

& A. Whitmer, MA716 a<br />

AY260563 AY255868<br />

U. pertusa Kjellman Tan et al. 1999 AJ234321 na<br />

U. pseudocurvata Koeman et van den Hoek Tan et al. 1999 AJ234312 AY255869<br />

U. rigida C. Agardh Cádiz, Spain. Coll. J. Berges AY260565 na<br />

U. rotundata Bliding Coat et al. 1998 na na<br />

U. sc<strong>and</strong>inavica Bliding Tan et al. 1999 AJ234317 AY255870<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong> sp. I Coihuin, Puerto Montt, Chile. 17 Oct 2000. Coll. J.R.<br />

Waal<strong>and</strong><br />

AY260566 AY255871<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong> sp. II Tamarama, Sydney, NSW. 9 Aug 1999. Coll. G.<br />

Zucc<strong>are</strong>llo<br />

AY260567 AY255872<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong> sp. III Newport Beach, CA, USA. 15 Jun 1999. Coll. H.S.<br />

Hayden & S. Murray<br />

AY260568 AY255873<br />

U. stenophylla Setchell et Gardner Seattle, WA, USA. 2 Jun 2000. Coll. H.S. Hayden,<br />

MA721 a<br />

AY260569 AY255874<br />

U. taeniata (Setchell in Collins, Holden et Setchell) Monterey, CA, USA. 17 Jun 1999. Coll. H.S. Hayden,<br />

Setchell et Gardner<br />

MA722 a<br />

AY262335 AY255875<br />

Umbraulva olivascens (P.J.L Dangeard) Bae et I.K. Lee<br />

Outgroups<br />

Portaferry, Strangford Lough, N. Irel<strong>and</strong>. 5 May 2000.<br />

Coll. C.A. Maggs<br />

AY260564 AY255876<br />

Blidingia minima (Nägeli ex Ku¨ tzing) Kylin var. minima Bolinas, CA, USA. 16 Jun 2000. Coll. H.S. Hayden na AF499675<br />

Kornmannia leptoderma (Kjellman) Bliding Vancouver Is., B.C., Canada. 29 Jun 1999. Coll. H.S.<br />

Hayden<br />

na AF499661<br />

Percursaria percursa (C. Agardh) Rosenvinge MA230 a<br />

AY260570 AF499658<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong>ria obscura var. blyttii (Areschoug) Bliding Padilla Bay, WA, USA. 25 Apr 1997. Coll. H.S.<br />

Hayden<br />

AY260571 AF499657<br />

a Cultures <strong>are</strong> in the University of Washington Culture Collection (UWCC).<br />

279<br />

<strong>was</strong> carried out in a PTC-100 Programmable Thermal<br />

Controller (MJ Research, NJ, USA). Primers used to<br />

amplify <strong>and</strong> sequence ITS nrDNA <strong>and</strong> the rbcL gene <strong>are</strong><br />

listed in Table 2. A fragment containing ITS1, ITS2 <strong>and</strong><br />

the 5.8S ribosomal subunit <strong>was</strong> amplified using primers<br />

18S1505 <strong>and</strong> ENT26S, which anneal to the 18S <strong>and</strong> 26S<br />

ribosomal subunits, respectively. The reaction profile<br />

included an initial denaturation at 948C for 5 min,<br />

followed by 1 min at 948C <strong>and</strong> 3 min at 608C for 30<br />

cycles, <strong>and</strong> a final 10 min extension at 608C (Blomster et<br />

al., 1998). The rbcL gene <strong>was</strong> amplified using primers<br />

from Manhart (1994). These primers amplified the first<br />

1357 bp of the rbcL gene excluding primers. This

H. S. Hayden et al.<br />

Table 2. Primers used in this study for PCR amplification <strong>and</strong> sequencing<br />

Primer Sequence Target<br />

18S1505 a<br />

18S1763 b<br />

5.8S30 a<br />

5.8S142 a<br />

ENT26S c<br />

RH1 d<br />

rbc571 a<br />

rbc590 a<br />

1385r d<br />

fragment excludes the variable 3’ terminus <strong>and</strong> represents<br />

95% of the gene. The reaction profile included an<br />

initial denaturation at 948C for 3 min, followed by 35<br />

cycles of 1 min at 948C, 2 min at 458C <strong>and</strong> 3 min at<br />

658C. PCR products were run on 1.5% agarose gels<br />

(SeaKem LE, FMC Bioproducts), stained in a solution<br />

of 0.5 mg ml –1 ethidium bromide (Gibco BRL) <strong>and</strong><br />

visualized under UV light. Products were pooled then<br />

purified using a polyethylene glycol (PEG) precipitation<br />

(Sigma). Briefly, an equal volume of a 20% PEG – 8000/<br />

2.5M NaCl stock solution <strong>was</strong> added to pooled PCR<br />

product. Following mixing, solutions were incubated at<br />

378C for 15 min <strong>and</strong> microcentrifuged for 15 min. The<br />

supernatant <strong>was</strong> removed <strong>and</strong> the DNA pellet <strong>was</strong><br />

<strong>was</strong>hed twice in 80% cold ethanol, dried down <strong>and</strong><br />

resuspended in double-distilled, UV-treated water for<br />

sequencing. Purified PCR products were sequenced<br />

using a dideoxy chain termination protocol with the<br />

ABI Prism BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready<br />

Reaction Kit (PE Applied Biosystems). Both str<strong>and</strong>s of<br />

PCR products were sequenced on an automated DNA<br />

sequencer (ABI 377).<br />

Sequences for the rbcL gene were aligned using<br />

Clustal X (Thompson et al., 1997) <strong>and</strong> edited by eye.<br />

ITS nrDNA regions were aligned manu<strong>all</strong>y using Se-Al<br />

version 1.0a1. All positions of ITS1 <strong>and</strong> ITS2 that<br />

could <strong>not</strong> be aligned with confidence were removed<br />

prior to analyses. Sequence divergence values were<br />

calculated using uncorrected ‘p’ distances. Maximum<br />

parsimony (MP) <strong>and</strong> maximum likelihood (ML)<br />

analyses were performed for each data set using<br />

PAUP* version 4.0b8 (Swofford, 1999). A MP analysis<br />

<strong>was</strong> also conducted for a combined data set; however, a<br />

ML analysis of the combined data <strong>was</strong> <strong>not</strong> performed<br />

due to computational limitations. Prior to analysis of<br />

the combined data, the incongruence length difference<br />

test (ILD) of Farris et al. (1994), implemented in<br />

PAUP* as the partition homogeneity test, <strong>was</strong><br />

performed. This test assesses heterogeneity among<br />

user-designated partitions, e.g. genes or codon positions.<br />

A non-significant result indicates that userdesignated<br />

data partitions <strong>are</strong> <strong>not</strong> significantly different<br />

from r<strong>and</strong>om partitions of the combined data set.<br />

Congruent data partitions may then be combined in a<br />

5’ TCTTTGAAACCGTATCGTGA 3’ ITS1<br />

5’ GGTGAACCTGCGGAGGGATCATT 3’ ITS1<br />

5’ GCAACGATGAAGAACGCAGC 3’ ITS2<br />

5’ TATTCCGACGCTGAGGCAG 3’ ITS1<br />

5’ GCTTATTGATATGCTTAAGTTCAGCGGGT 3’ ITS2<br />

5’ ATGTCACCACAAACAGAAACTAAAGC 3’ rbcL<br />

5’ TGTTTACGAGGTGGTCTTGA 3’ rbcL<br />

5’ TCAAGACCACCTCGTAAACA 3’ rbcL<br />

5’ AATTCAAATTTAATTTCTTTCC 3’ rbcL<br />

a Primer name includes gene abbreviation <strong>and</strong> approximate position to which primer anneals in <strong>Ulva</strong>.<br />

b Modified from Blomster et al. (1998).<br />

c Blomster et al. (1998).<br />

d Manhart (1994).<br />

280<br />

single phylogenetic analysis (de Queiroz et al., 1995;<br />

Huelsenbeck et al., 1996). In MP analyses, <strong>all</strong><br />

characters <strong>and</strong> character state changes were weighted<br />

equ<strong>all</strong>y <strong>and</strong> gaps were coded as missing data. Heuristic<br />

searches were performed with tree bisection-reconnection<br />

(TBR), MulTrees <strong>and</strong> steepest descent options in<br />

effect. Ten replicate searches with r<strong>and</strong>omized taxon<br />

input were conducted to avoid local optima of most<br />

parsimonious trees. To comp<strong>are</strong> relative support for<br />

branches, 1000 bootstrap replications (Felsenstein,<br />

1985) were performed using heuristic searches with<br />

simple taxon addition, TBR <strong>and</strong> MulTrees options in<br />

effect.<br />

Prior to likelihood searches, several parameters were<br />

estimated using PAUP*. Base frequencies, transition to<br />

transversion ratio, proportion of invariable sites <strong>and</strong> siteto-site<br />

rate heterogeneity were estimated under maximum<br />

likelihood criteria from an optimal parsimony topology<br />

(Swofford et al., 1996). These parameters were then set to<br />

estimated values in ensuing ML searches. Based on these<br />

estimations, substitution bias <strong>was</strong> modelled by the<br />

general time-reversible model (Yang, 1994a) with invariable<br />

sites (Hasegawa et al., 1985), <strong>and</strong> rate heterogeneity<br />

<strong>was</strong> modelled using the gamma distribution method<br />

(Yang, 1994b) with four discrete rate categories <strong>and</strong> a<br />

single shape parameter (alpha) (model GTR + I + G). A<br />

heuristic search <strong>was</strong> conducted using an optimal starting<br />

tree from MP analyses with TBR, MulTrees <strong>and</strong> steepest<br />

descent options in effect.<br />

Results<br />

MP <strong>and</strong> ML analyses were conducted using 471<br />

aligned characters from the spacers <strong>and</strong> the 5.8S<br />

gene. Boundaries for the 5.8S gene were defined<br />

according to Thompson & Herrin (1994). The 5’<br />

end of ITS1 <strong>and</strong> the 3’ end of ITS2 were determined<br />

according to van de Peer et al. (2000) <strong>and</strong> Wuyts et<br />

al. (2001), respectively. The ITS1 spacer ranged in<br />

length from 154 to 218 bp <strong>and</strong> the ITS2 from 162<br />

to 184 bp among the surveyed taxa. A total of 141

<strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> <strong>are</strong> <strong>not</strong> <strong>distinct</strong> genera<br />

characters were excluded from the spacers prior to<br />

analyses because positional homology could <strong>not</strong> be<br />

confidently determined. In contrast, the 5.8S<br />

nrDNA gene <strong>was</strong> 158 bp in <strong>all</strong> surveyed taxa <strong>and</strong><br />

had only 14 variable sites. The lengths of the<br />

spacers <strong>and</strong> the 5.8S gene <strong>are</strong> comparable to those<br />

of other taxa in the Ulvophyceae (Bakker et al.,<br />

1995a, b; van Oppen, 1995; Friedl, 1996).<br />

Alignment of rbcL sequences required the addition<br />

of a single gap of three nucleotides in <strong>all</strong><br />

sequences relative to the outgroup Kornmannia<br />

leptoderma. The additional amino acid in K.<br />

leptoderma is present in other green algae sequenced<br />

to date (e.g. Yang et al., 1986; Kono et<br />

al., 1991; Manhart, 1994; Sherwood et al., 2000),<br />

with the exception of other <strong>Ulva</strong>les (Sherwood et<br />

al., 2000; Hayden & Waal<strong>and</strong>, 2002). The final<br />

rbcL alignment included 1357 characters.<br />

The ILD test using partitions for rbcL versus ITS<br />

nrDNA <strong>was</strong> non-significant (p = 0.99); thus, data<br />

sets were combined in a single analysis. The<br />

alignment of combined data included <strong>all</strong> taxa, <strong>and</strong><br />

rbcL positions were coded as missing data for the<br />

taxa in which this gene <strong>was</strong> <strong>not</strong> sequenced (Table 1).<br />

MP analysis of ITS nrDNA data resulted in 90<br />

optimal trees of 347 steps. There were 147 variable<br />

sites in the analysed data set, <strong>and</strong> 108 sites were<br />

parsimony-informative. The strict consensus of<br />

most-parsimonious trees is shown in Fig. 1a. The<br />

ML analysis resulted in a single tree (Fig. 2) which<br />

is similar to the strict consensus tree based on ITS<br />

nrDNA sequences (Fig. 1a). Minor differences<br />

between trees can be seen in the clades comprising<br />

U. lactuca, U. australis, etc., <strong>and</strong> U. stenophylla, E.<br />

prolifera, etc. <strong>and</strong> the positions of E. flexuosa <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> sp. II.<br />

Fig. 1. Comparison of strict consensus trees derived from (a) nuclear ribosomal ITS sequence data <strong>and</strong> (b) the chloroplastencoded<br />

rbcL gene. Bootstrap percentages (1000 replicates samples) <strong>are</strong> shown above branches. Nodes with bootstrap values of<br />

less than 50% <strong>are</strong> <strong>not</strong> labelled.<br />

281

H. S. Hayden et al.<br />

Fig. 2. Phylogram of sampled taxa based on ML analysis of ITS nrDNA sequences ( – lnL = 2424.316). Bootstrap percentages<br />

(1000 replicates samples) <strong>are</strong> shown above branches. Nodes with bootstrap values of less than 50% <strong>are</strong> <strong>not</strong> labelled.<br />

MP analysis of the rbcL data set resulted in<br />

six optimal trees of 473 steps. The strict<br />

consensus tree is shown in Fig. 1b. There were<br />

291 variable sites in the data set, <strong>and</strong> 138 sites<br />

were parsimony-informative. Clades with bootstrap<br />

values of 50% or greater in the consensus<br />

282<br />

tree (Fig. 1b) were also resolved in the ML tree<br />

(Fig. 3) with one exception. In the ML tree<br />

Umbraulva olivascens rather than <strong>Ulva</strong>ria obscura<br />

var. blyttii is basal in the clade that is<br />

sister to the remaining <strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong><br />

species.

<strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> <strong>are</strong> <strong>not</strong> <strong>distinct</strong> genera<br />

Fig. 3. Phylogram of a subset of sampled taxa based on ML analysis of rbcL sequences ( – lnL = 4435.492). Bootstrap<br />

percentages (1000 replicates samples) <strong>are</strong> shown above branches. Nodes with bootstrap values of less than 50% <strong>are</strong> <strong>not</strong> labelled.<br />

MP analysis of the combined data resulted in 117<br />

trees of 824 steps (Fig. 4). A total of 1828<br />

characters were included in the analysis, of which<br />

246 were parsimony-informative. Clades resolved<br />

in the combined data consensus tree (Fig. 4) <strong>are</strong><br />

similar to those in the ITS nrDNA <strong>and</strong> rbcL<br />

283<br />

consensus trees (Fig. 1) but they have higher<br />

bootstrap values. In <strong>all</strong> trees a clade consisting of<br />

<strong>all</strong> <strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> species is strongly<br />

supported. The topology of the deepest branches<br />

within this clade varies among trees; however, in <strong>all</strong><br />

analyses there <strong>are</strong> well-supported clades which

H. S. Hayden et al.<br />

Fig. 4. Strict consensus of 117 most parsimonious trees of 824 steps from the analysis of combined ITS nrDNA <strong>and</strong> rbcL<br />

sequences. Bootstrap percentages (1000 replicate samples <strong>are</strong> shown above branches. Nodes with bootstrap values of less than<br />

50% <strong>are</strong> <strong>not</strong> labelled.<br />

contain both <strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> species.<br />

Examples of such clades include: (1) E. compressa<br />

<strong>and</strong> U. pseudocurvata; (2) these taxa plus E.<br />

intestinalis <strong>and</strong> E. intestinaloides; (3) U. californica<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> sp. I; (4) these taxa plus<br />

284<br />

Chloropelta caespitosa; <strong>and</strong> (5) E. clathrata plus<br />

several species of <strong>Ulva</strong>. Several additional clades<br />

that have moderate to strong bootstrap values in<br />

<strong>all</strong> consensus trees contain either <strong>Ulva</strong> or <strong>Enteromorpha</strong><br />

species.

<strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> <strong>are</strong> <strong>not</strong> <strong>distinct</strong> genera<br />

Sequence divergence among the ITS nrDNA<br />

sequences ranged from 0 between U. fasciata <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Ulva</strong> sp. II to nearly 18% between Percursaria<br />

percursa <strong>and</strong> some species of <strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong>.<br />

The Umbraulva olivascens sequence <strong>was</strong><br />

approximately 7% divergent from <strong>Ulva</strong>ria obscura<br />

var. blyttii <strong>and</strong> P. percursa <strong>and</strong> more than 13%<br />

divergent from <strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> sequences.<br />

The greatest divergence among ingroup taxa<br />

(minus U. olivascens) <strong>was</strong> 13.3% between U.<br />

taeniata <strong>and</strong> E. compressa. Divergence among<br />

species found in mixed <strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong><br />

clades varied. There <strong>was</strong> 0.2% divergence between<br />

E. compressa <strong>and</strong> U. pseudocurvata <strong>and</strong> approximately<br />

6% between these taxa <strong>and</strong> E. intestinalis.<br />

Sequence divergence <strong>was</strong> 1.3% between U. californica<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> sp. I, approximately 3%<br />

between these taxa <strong>and</strong> C. caespitosa, <strong>and</strong> 5.0 –<br />

6.5% between E. clathrata <strong>and</strong> closely related <strong>Ulva</strong><br />

taxa.<br />

Sequence divergence values in the rbcL data set<br />

were gener<strong>all</strong>y lower than those observed in the ITS<br />

nrDNA data set. They ranged from 0.1% between<br />

two pairs of taxa, U. lactuca /U. fenestrata <strong>and</strong> E.<br />

compressa/U. pseudocurvata, to nearly 14% between<br />

ingroup taxa <strong>and</strong> the two outgroups, K.<br />

leptoderma <strong>and</strong> B. minima var. minima. Umbraulva<br />

olivascens <strong>was</strong> less than 3% divergent from <strong>Ulva</strong>ria<br />

obscura var. blyttii <strong>and</strong> P. percursa <strong>and</strong> 3.7 – 4.4%<br />

divergent from <strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> taxa. In<br />

mixed clades, there <strong>was</strong> 1.9% sequence divergence<br />

between E. intestinalis <strong>and</strong> either E. compressa or<br />

U. pseudocurvata. Divergence <strong>was</strong> 0.5% between U.<br />

californica <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> sp. I, 0.7 – 0.8%<br />

between C. caespitosa <strong>and</strong> these taxa, <strong>and</strong> 0.9 –<br />

1.6% between E. clathrata <strong>and</strong> related <strong>Ulva</strong> species.<br />

The greatest sequence divergence among ingroup<br />

taxa (minus U. olivascens) <strong>was</strong> 3.6%.<br />

Discussion<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> together form a strongly<br />

supported clade in <strong>all</strong> analyses, but they <strong>are</strong> <strong>not</strong><br />

monophyletic. These results, combined with earlier<br />

findings from molecular (Blomster et al., 1999; Tan<br />

et al., 1999) <strong>and</strong> culture studies (Gayral, 1959,<br />

1967; Føyn, 1960, 1961; Løvlie, 1964; Provasoli,<br />

1965; Berglund, 1969; Kapraun, 1970; Fries, 1975;<br />

Bonneau, 1977; Provasoli & Pintner, 1980), provide<br />

strong evidence that <strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> <strong>are</strong><br />

<strong>not</strong> <strong>distinct</strong> evolutionary entities <strong>and</strong> should <strong>not</strong> be<br />

recognized as separate genera.<br />

Addition<strong>all</strong>y, Chloropelta caespitosa is nested<br />

among <strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> taxa. Tanner (1979,<br />

1980) described C. caespitosa on the basis of its<br />

unique developmental pattern. Early in development,<br />

cells in the tubular germling undergo one<br />

285<br />

division producing a distromatic tubular germling<br />

<strong>not</strong> seen in other <strong>Ulva</strong>ceae. Rupture of the apical<br />

end of the germling <strong>and</strong> continued growth eventu<strong>all</strong>y<br />

result in a peltate distromatic blade (Tanner,<br />

1980). Despite its unique development, which is<br />

very <strong>distinct</strong>ive in culture (Hayden, personal<br />

observation), C. caespitosa groups with U. californica<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> sp. I from California in <strong>all</strong><br />

trees, <strong>and</strong> bootstrap support for this grouping is<br />

strong (Fig. 4). Thus, the type <strong>and</strong> only species of<br />

Chloropelta should also be transferred to <strong>Ulva</strong>.<br />

However, because the resulting binomial would be<br />

a later homonym of <strong>Ulva</strong> caespitosa Withering<br />

(Bot. Arr. Veg. Gt. Brit.: 735. 1776), the basionym<br />

of Catenella caespitosa (Withering) L. Irvine (J.<br />

Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK, 56: 590. 1976), the following<br />

substitute name is proposed:<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong> tanneri H.S. Hayden & J.R. Waal<strong>and</strong>, nom.<br />

nov.<br />

Replaced name: Chloropelta caespitosa C.E.<br />

Tanner (J. Phycol., 16: 130, figs 2 – 49. 1980).<br />

In the ensuing discussion, the clade comprising<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong>, <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> <strong>and</strong> Chloropelta taxa will be<br />

referred to as the <strong>Ulva</strong> clade. Umbraulva olivascens<br />

is discussed further below.<br />

Mixed clades of <strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong><br />

Within the <strong>Ulva</strong> clade several subclades consisting<br />

of both distromatic <strong>and</strong> tubular species received<br />

strong support. E. compressa <strong>and</strong> U. pseudocurvata<br />

<strong>are</strong> <strong>all</strong>ied with 100% bootstrap support in trees<br />

from <strong>all</strong> analyses. E. compressa is common in the<br />

British Isles <strong>and</strong> is morphologic<strong>all</strong>y similar to the<br />

type species of <strong>Enteromorpha</strong>, E. intestinalis;<br />

however, these two species have been shown to be<br />

<strong>distinct</strong> evolutionary entities using crossing experiments<br />

(Larsen, 1981) <strong>and</strong> phylogenetic analysis of<br />

ITS nrDNA sequences (Blomster et al., 1998). <strong>Ulva</strong><br />

pseudocurvata is a typical <strong>Ulva</strong> species with a<br />

distromatic, medium to light green membranaceous<br />

blade (Koeman & van den Hoek, 1981). ITS<br />

nrDNA sequence divergence among isolates of<br />

these two species <strong>was</strong> similar to levels of divergence<br />

within clearly monospecific groupings, such as<br />

geographic<strong>all</strong>y <strong>distinct</strong> collections of E. intestinalis<br />

<strong>and</strong> E. compressa (up to 2.3%) (Blomster et al.,<br />

1998). Distances between rbcL sequences among<br />

conspecifics range from 0.0 to 0.4% (Hayden,<br />

2001). Thus, divergence between E. compressa <strong>and</strong><br />

U. pseudocurvata in the rbcL gene ( 5 0.1%) is also<br />

within the range of conspecifics.<br />

A<strong>not</strong>her mixed <strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> pair that<br />

is well supported in trees is U. californica <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> sp. I from California. U. californica<br />

is a distromatic species found <strong>along</strong> the Pacific

H. S. Hayden et al.<br />

coast of North America from the Alaska Peninsula<br />

to Baja California. Morphological <strong>and</strong> culture<br />

studies have revealed that while this species has a<br />

wide range of environment<strong>all</strong>y influenced blade<br />

forms, it shows a <strong>distinct</strong>ive developmental pattern<br />

which clearly separates it from other species of<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong> (Tanner, 1979, 1986). These developmental<br />

characteristics <strong>are</strong> the presence of a germination<br />

tube <strong>and</strong> the early development of an extensive<br />

basal system of rhizoids (Tanner, 1986). <strong>Enteromorpha</strong><br />

sp. I, a tubular alga with a branched<br />

morphology similar to E. prolifera, has a similar<br />

distribution to that of U. californica (Hayden,<br />

2001). Divergence between these taxa is 1.3% <strong>and</strong><br />

0.5% for ITS nrDNA <strong>and</strong> rbcL sequences,<br />

respectively – values <strong>not</strong> much greater than those<br />

for E. compressa <strong>and</strong> U. pseudocurvata.<br />

One explanation for these observations is that<br />

these paired taxa represent two phases in the life<br />

history of a single species. However, an isomorphic<br />

life history has been observed in E. compressa<br />

(Bliding, 1968), U. pseudocurvata (Koeman & van<br />

den Hoek, 1981) <strong>and</strong> U. californica (Tanner, 1979,<br />

1986). Further, the type of sexual life history is<br />

used to delimit the <strong>Ulva</strong>les (isomorphic) from the<br />

Ulotrichales (heteromorphic) (Kornmann, 1965),<br />

<strong>and</strong> its use at this taxonomic level is supported by<br />

molecular <strong>and</strong> ultrastructural data (Floyd &<br />

O’Kelly, 1984; Hayden & Waal<strong>and</strong>, 2002). Thus,<br />

an alternation of heteromorphic generations in this<br />

clade is unlikely. An alternative explanation is that<br />

these pairs represent separate species <strong>and</strong> that<br />

observed low sequence divergences <strong>are</strong> due either to<br />

recent speciation, i.e. they <strong>are</strong> in the early stages of<br />

diverging from one a<strong>not</strong>her, or to other factors,<br />

such as convergent evolution. Data supporting<br />

their status as individual species exist. In Tan et al.<br />

(1999) the monophyly of E. compressa accessions is<br />

strongly supported by ITS nrDNA analyses.<br />

Similarly, geographic<strong>all</strong>y <strong>distinct</strong> isolates of U.<br />

californica form a clade, as do isolates of <strong>Enteromorpha</strong><br />

sp. I in ITS nrDNA <strong>and</strong> rbcL trees<br />

(Hayden, 2001). Thus, these taxa <strong>are</strong> considered<br />

separate species.<br />

Tan et al. (1999) hypothesized that a reversible<br />

morphogenetic switch (or switches) controls gross<br />

morphology in these algae: the switch from a blade<br />

to a tube morphology (or vice versa) is activated<br />

infrequently in nature perhaps by various environmental<br />

cues, <strong>and</strong> it is more frequent in culture due<br />

to stresses unique to artificial systems. It is clear<br />

from the position of <strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> taxa<br />

in the present trees <strong>and</strong> those of Tan et al. (1999)<br />

that gross morphology has been fixed in certain<br />

lineages. It is unclear whether the same mechanism(s)<br />

is involved in culture experiments. Culture<br />

studies citing flexibility of form show <strong>Ulva</strong> taxa<br />

with tubular or globular morphologies (Løvlie,<br />

286<br />

1964; Gayral, 1959, 1967; Bonneau, 1977; Føyn,<br />

1960, 1961), but although monostromatic sheets<br />

<strong>are</strong> formed under green tide conditions (Blomster<br />

et al., 2002) there <strong>are</strong> no culture studies which show<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> with distromatic morphologies.<br />

Further, observations of cultures suggest that<br />

altered morphologies in cultures of <strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>are</strong> <strong>not</strong><br />

uncommon (Hayden, personal observation). With<br />

the exception of Percursaria, <strong>all</strong> ulvacean taxa pass<br />

through a tubular stage in development. Distromatic<br />

species growing without exposure to wave<br />

action, desiccation or other environmental factors<br />

may <strong>not</strong> develop norm<strong>all</strong>y beyond the tubular<br />

stage. Some culture studies of <strong>Ulva</strong> species have <strong>not</strong><br />

reported altered morphology (e.g. Bliding, 1963,<br />

1968; Kapraun, 1970; Tanner, 1979). It is possible<br />

that certain culture conditions foster normal<br />

development, or that some species <strong>are</strong> capable of<br />

normal development in culture while others <strong>are</strong><br />

<strong>not</strong>. Further research, including field outplanting<br />

of culture material, may help to resolve these issues<br />

<strong>and</strong> lead to a better underst<strong>and</strong>ing of the mechanism(s)<br />

underlying morphology in these algae.<br />

Morphological synapomorphies<br />

A comparison of traits for surveyed species<br />

revealed few synapomorphies. Given that clades<br />

<strong>are</strong> <strong>not</strong> defined on the basis of distromatic versus<br />

tubular morphology, it is <strong>not</strong> surprising that they<br />

<strong>are</strong> also <strong>not</strong> defined by the type of blade (e.g.<br />

exp<strong>and</strong>ed versus linear) or tube (e.g. branched<br />

versus unbranched). Other characters <strong>are</strong> too<br />

conserved, e.g. mode of reproduction (Floyd &<br />

O’Kelly, 1984) or too variable, e.g. cell size,<br />

number of pyrenoids (Tanner, 1979; Phillips,<br />

1988). The difficulty in identifying morphological<br />

synapomorphies for clades in molecular-based trees<br />

is <strong>not</strong> unique to this group of seaweeds (e.g. Stiller<br />

& Waal<strong>and</strong>, 1993). These results reinforce the need<br />

for great caution when using morphological<br />

characters in comparative, taxonomic or systematic<br />

studies in this <strong>and</strong> other groups of morphologic<strong>all</strong>y<br />

simple algae. Characters commonly used to distinguish<br />

species <strong>are</strong> listed in Table 3. Of these<br />

characters, only two potential synapomorphies<br />

were identified. E. compressa, U. pseudocurvata,<br />

E. intestinalis <strong>and</strong> E. intestinaloides <strong>are</strong> <strong>all</strong> described<br />

as having ‘hood’- or ‘cup’-shaped chloroplasts<br />

which <strong>are</strong> predominantly oriented apic<strong>all</strong>y<br />

in cells of the middle <strong>and</strong> apical regions (Blomster<br />

et al., 1998; Koeman & van den Hoek, 1981, 1982).<br />

Some taxa, such as U. lactuca <strong>and</strong> U. rigida, have<br />

been observed to have similarly shaped chloroplasts<br />

in these th<strong>all</strong>us regions, but their chloroplasts<br />

<strong>are</strong> variously oriented rather than apic<strong>all</strong>y<br />

oriented (Koeman & van den Hoek, 1981). Other<br />

taxa have chloroplasts which completely fill cells in

<strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> <strong>are</strong> <strong>not</strong> <strong>distinct</strong> genera<br />

Table 3. Characters used to delimit species of <strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> based on Koeman <strong>and</strong> van den Hoek (1981)<br />

<strong>and</strong> Bliding (1963, 1968). Characters <strong>not</strong>ed with (E) <strong>and</strong> (U)<br />

<strong>are</strong> used only in <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Ulva</strong>, respectively.<br />

Character<br />

Gross morphology, including colour <strong>and</strong> texture of mature plant<br />

Structure of plant base<br />

Arrangement <strong>and</strong> shape of cells in surface view<br />

Structure of branch tips (E)<br />

Number of pyrenoids per cell<br />

Shape of chloroplast in surface view<br />

Cell size at base, middle <strong>and</strong> apex of th<strong>all</strong>us<br />

Height-to-width ratio of cells in cross section (U)<br />

Th<strong>all</strong>us thickness (U)<br />

Morphology of young germling<br />

Mode of reproduction<br />

Ecology<br />

surface view. Neither of the latter chloroplast<br />

positions appears to delimit clades. Studies by<br />

Britz & Briggs (1976, 1983) <strong>and</strong> Mishkind et al.<br />

(1979) showed that chloroplasts in some <strong>Ulva</strong><br />

species migrate within the cells according to a<br />

circadian rhythm. Such movement <strong>was</strong> <strong>not</strong> detected<br />

in certain <strong>Ulva</strong>les, including an alga<br />

identified as E. intestinalis (Britz & Briggs, 1976).<br />

These studies may suggest that chloroplast position<br />

is too variable for use in systematic studies.<br />

Conversely, the presence of diurnal changes in<br />

chloroplast position may prove to be a synapomorphy,<br />

but at present this phenomenon has been<br />

studied in only a limited number of taxa.<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong> species in the clade with E. clathrata (Fig. 4)<br />

sh<strong>are</strong> the presence of microscopic teeth <strong>along</strong> the<br />

blade margin. E. clathrata has a tubular morphology<br />

<strong>and</strong> therefore lacks a blade margin; however,<br />

one of the diagnostic characters for this species is<br />

the presence of ‘spine-like’ short branchlets<br />

throughout the th<strong>all</strong>us (Bliding, 1963; Blomster et<br />

al., 1999, as E. muscoides). These branchlets have a<br />

broad base composed of several cells <strong>and</strong> a narrow<br />

tip which typic<strong>all</strong>y ends in a single cell. Their<br />

appearance is reminiscent of marginal teeth observed<br />

in <strong>Ulva</strong> species (Dion et al., 1998); however,<br />

marginal dentition has been described in two other<br />

surveyed taxa – U. rotundata (Bliding, 1968) <strong>and</strong> U.<br />

australis (Phillips, 1988; Woolcott & King, 1999) –<br />

which were <strong>not</strong> placed in the same clade as E.<br />

clathrata, suggesting that this trait has evolved<br />

more than once in these algae.<br />

Comparison with other molecular studies<br />

Relationships of taxa in the present trees <strong>are</strong><br />

gener<strong>all</strong>y congruent with those in Tan et al.<br />

(1999) <strong>and</strong> Blomster et al. (1999), although the<br />

latter study included a relatively sm<strong>all</strong> number of<br />

287<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> species. Differences in the<br />

positions of three taxa between the present study<br />

<strong>and</strong> that of Tan et al. (1999) <strong>are</strong> <strong>not</strong>eworthy. In the<br />

present study, Umbraulva olivascens is <strong>all</strong>ied with<br />

the designated outgroups, <strong>Ulva</strong>ria <strong>and</strong> Percursaria,<br />

<strong>and</strong> these three taxa comprise the sister group to<br />

the <strong>Ulva</strong> clade in the rbcL trees. In Tan et al. (1999)<br />

U. olivascens (as <strong>Ulva</strong> olivascens) occupied a basal<br />

position among the sampled <strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong><br />

leading to the conclusion that <strong>all</strong> <strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> species form a clade. However,<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong>ria <strong>and</strong> Percursaria were <strong>not</strong> included in their<br />

study, rather Blidingia (<strong>Ulva</strong>les) <strong>and</strong> Gloeotilopsis<br />

(Ulotrichales) served as the sole outgroups <strong>and</strong><br />

introduced a relatively long branch into the ITS<br />

nrDNA-based trees.<br />

Umbraulva olivascens, found in the northeast<br />

Atlantic <strong>and</strong> Mediterranean, <strong>was</strong> named for its<br />

characteristic olive-green th<strong>all</strong>us (Dangeard, 1951,<br />

1961, as <strong>Ulva</strong> olivascens). Other traits which<br />

distinguish this taxon from <strong>Ulva</strong> species include<br />

the presence of (1) relatively large cells in the<br />

mature plant, (2) characteristic<strong>all</strong>y rounded cells in<br />

apical regions, <strong>and</strong> (3) a marginal region of sterile<br />

cells distal to zoosporangia that detaches in<br />

‘threadlike masses’ following reproductive cell<br />

release (Bliding, 1968; Burrows, 1991). At present,<br />

there <strong>are</strong> no clear morphological traits that would<br />

suggest affinities of U. olivascens to <strong>Ulva</strong>ria or<br />

Percursaria other than its early development, which<br />

is typic<strong>all</strong>y ulvacean (Bliding, 1968), <strong>and</strong> the<br />

relationship between these three taxa requires<br />

further investigation.<br />

The positions of two additional <strong>Ulva</strong> species, U.<br />

fenestrata <strong>and</strong> U. californica, differ in the present<br />

trees comp<strong>are</strong>d with those in Tan et al. (1999). Tan<br />

et al. (1999) found that U. fenestrata <strong>was</strong> <strong>all</strong>ied<br />

with U. armoricana, <strong>and</strong> their collection of U.<br />

californica appe<strong>are</strong>d in a clade of multiple geographic<strong>all</strong>y<br />

<strong>distinct</strong> collections of U. lactuca, the<br />

type species of <strong>Ulva</strong>. In the present trees the close<br />

relationship of U. fenestrata <strong>and</strong> U. lactuca is<br />

strongly supported. Sequence divergence values<br />

between these taxa <strong>are</strong> within the range of<br />

conspecifics: 0.5% <strong>and</strong> 0.1% for ITS nrDNA <strong>and</strong><br />

rbcL, respectively (Blomster, 1998, 1999; Hayden,<br />

2001). A study of <strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> from the<br />

northeast Pacific including collections of U. californica<br />

<strong>and</strong> U. fenestrata from throughout their<br />

distribution ranges found similar relationships of<br />

these species to others (Hayden, 2001). This<br />

suggests that the U. californica <strong>and</strong> U. fenestrata<br />

collections in Tan et al. (1999) were misidentified.<br />

Given the morphological plasticity exhibited by<br />

these taxa, <strong>and</strong> overlapping distribution ranges <strong>and</strong><br />

ecology (Tanner, 1979, 1986; Gabrielson et al.,<br />

2000), it is <strong>not</strong> unreasonable that an individual of<br />

U. californica would be misidentified as U.

Table 4. Valid <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> binomials with authorities, in current usage (Wynne, 1998; Guiry & NicDonncha, 2002) or otherwise of interest as indicated, with existing binomials in <strong>Ulva</strong>, new<br />

combinations in <strong>Ulva</strong>, or explanations why binomials in <strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>are</strong> blocked (Index Nominum Algarum, 2002). Infraspecific taxa <strong>are</strong> omitted<br />

Binomial in <strong>Enteromorpha</strong><br />

Basionym (if different)<br />

Binomial in <strong>Ulva</strong><br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> acanthophora Ku¨ tzing (1849) Sp. Alg.: 479<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong> acanthophora (Ku¨ tzing) comb. nov.<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> atroviridis (‘atro-viridis’)<br />

(Levring) M.J. Wynne (1986)<br />

Nova Hedwigia 43: 324<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong> atroviridis Levring (1938) Lunds Univ. A˚ rsskr. N.F. Avd. 2,<br />

34(9): 4, fig. 2; pl. 1: fig. 1<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> bulbosa (Suhr) Montagne (1846) Voy. Bonite, Crypt.<br />

Cell.: 33<br />

Solenia bulbosa Suhr (1839) Flora 22: 72, pl. IV: fig. 46<br />

Solenia bulbosa Suhr <strong>was</strong> transferred to <strong>Ulva</strong> by Trevisan (Fl.<br />

Eugan.: 51. 1842), but <strong>Ulva</strong> bulbosa (Suhr) Trevisan is a later<br />

homonym of <strong>Ulva</strong> bulbosa Palisot de Beauvois (Fl. Ow<strong>are</strong> 1: 20, pl.<br />

XIII: fig. 1. 1805) from Ghana, of uncertain identity<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> chaetomorphoides Børgesen (1911) Bot. Tidsskr. 31:<br />

149, fig. 12<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong> chaetomorphoides (Børgesen) comb. nov.<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> clathrata (Roth) Greville<br />

Conferva clathrata Roth (1806) Cat. bot. III: 175 – 8<br />

Type locality; collector<br />

Type material (with relevant reference if any)<br />

Type or other authentic material examined<br />

Bay of Isl<strong>and</strong>s, New Zeal<strong>and</strong>; J.D. Hooker<br />

Type: L 938.19.134 (Womersley, 1956)<br />

Hotel Rocks, Port Nolloth, Cape Province, South Africa<br />

Type: GB (Wynne, 1986)<br />

Peru<br />

Type: L 1391 sheet 40 (Ricker, 1987)<br />

Material examined: BM, Peru, ex herb. Montagne<br />

Bovoni Lagoon, St Thomas, Virgin Isl<strong>and</strong>s<br />

Holotype: C (Bliding, 1963)<br />

Type locality: Fehmarn, SW Baltic (original material missing)<br />

Neotype: LD 137737 from L<strong>and</strong>skoma, Baltic Oresund, 1829<br />

(Blomster et al., 1999; illustrated in Bliding 1963, figs 69a, b)<br />

Taxonomic <strong>not</strong>es (non-type material examined)<br />

Currently placed in synonymy with E. clathrata but we concur with<br />

Adams (1994) that New Zeal<strong>and</strong> material might be <strong>distinct</strong> (E.<br />

acanthophora, BM, Chatham Isl<strong>and</strong>s, H.E. Maltby xi 1905)<br />

South African endemic resembling E. linza (Wynne, 1986; Stegenga<br />

et al., 1997)<br />

Highly morphologic<strong>all</strong>y variable, from tubular to cornucopia-like<br />

(Ricker, 1987). Many putative synonyms. As the <strong>Ulva</strong> binomial<br />

can<strong>not</strong> be used, a synonym is chosen here. The most appropriate<br />

geographic<strong>all</strong>y is E. hookeriana Kützing (see below)<br />

Very finely branched material, often growing with Rhizoclonium.<br />

(BM, Puerto Rico, various collections)<br />

Heterotypic synonyms include:<br />

E. crinita Nees (1820) Hor. Phys. Berol.: Index [2]<br />

E. muscoides (Clemente) J. Cremades in J. Cremades & J.L. Pe´ rez-<br />

Cirera (1990) Anales Jard. Bot. Madrid 47: 489, based on <strong>Ulva</strong><br />

muscoides Clemente (1807) Ensayo sobre las Variedades de la Vid:<br />

320 (erroneously regarded as the oldest valid name by Blomster et<br />

al., 1999)<br />

E. ramulosa (J.E. Smith) Carmichael<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> welwitschii J. Agardh (1883) Alg. Syst. 3: 143. Tagus<br />

R. near Aldea, Portugal; Welwitsch, Phyc. Lusitan. 289. Syntypes:<br />

BM<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> gelatinosa Kützing (1849) Sp. Alg.: 482. Canary<br />

Isl<strong>and</strong>s, Despreaux<br />

non <strong>Ulva</strong> gelatinosa Ku¨ tzing (1856) Tab. Phyc. VI, Tab. 32<br />

(continued )<br />

H. S. Hayden et al.<br />

288

Table 4. (continued )<br />

Binomial in <strong>Enteromorpha</strong><br />

Basionym (if different)<br />

Binomial in <strong>Ulva</strong><br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> compressa (<strong>Linnaeus</strong>) Nees (1820) Hor. Phys. Berol.:<br />

Index [2]<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong> compressa <strong>Linnaeus</strong> (1753) Sp. Pl. 2: 1163<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> crassimembrana V.J. Chapman (1956) J. Linn. Soc.<br />

London, Bot. 55: 424, fig. 74<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong> crassimembrana (V.J. Chapman) comb. nov.<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> flexuosa (Wulfen) J. Agardh (1883) Alg. Syst. 3: 126<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong> flexuosa Wulfen (1803) Crypt. Aquat.: 1., new name for<br />

Conferva flexuosa Roth 1800 (nom. illeg.; see Silva et al., 1996,<br />

p. 732)<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> hookeriana Ku¨ tzing (1849) Sp. Alg.: 480<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong> hookeriana (Ku¨ tzing) comb. nov.<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> intestinalis (<strong>Linnaeus</strong>) Nees (1820) Hor. Phys. Berol.:<br />

Index [2]<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong> intestinalis <strong>Linnaeus</strong> (1753) Sp. Pl. 2: 1163<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> intestinaloides R.P.T. Koeman & C. van den Hoek<br />

(1982) Arch. Hydrobiol. Suppl. 63 [Algol. Stud. 32]: 321, figs. 115 –<br />

129<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong> intestinaloides (R.P.T. Koeman & C. van den Hoek) comb. nov.<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> kylinii Bliding 1948: 199 – 204, figs 1 – 3<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong> kylinii (Bliding) comb. nov.<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> lingulata J. Agardh (1883) Alg. Syst. 3: 143<br />

Can<strong>not</strong> be transferred to <strong>Ulva</strong> because of the prior existence of <strong>Ulva</strong><br />

lingulata A.P. de C<strong>and</strong>olle (in Lamarck & de C<strong>and</strong>olle, 1805, Fl.<br />

Franc. ed. 3, 2: 14), of uncertain identity but most likely referable to<br />

Hypoglossum hypoglossoides<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> linza (<strong>Linnaeus</strong>) J. Agardh (1883) Alg. Syst. 3: 134.<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong> linza <strong>Linnaeus</strong> (1753) Sp. Pl. 2: 1163.<br />

Type locality; collector<br />

Type material (with relevant reference if any)<br />

Type or other authentic material examined<br />

Bognor, Sussex, Engl<strong>and</strong>?<br />

Typotype (= epitype): OXF. Lectotype: Dillenius (1742: pl. 9, fig. 8;<br />

Blomster et al., 1998)<br />

Cape Maria van Diemen, New Zeal<strong>and</strong><br />

Type: AKU (Chapman, 1956)<br />

Duino, near Trieste, Italy<br />

Holotype: W, Wulfen no. 23 (Bliding, 1963)<br />

Berkeley Sound, Falkl<strong>and</strong> Isl<strong>and</strong>s; J.D. Hooker<br />

Type: L? Isotype: BM, iv 1842<br />

Woolwich, London, Engl<strong>and</strong>?<br />

Typotype (= epitype): OXF. Lectotype: Dillenius (1742: pl. 9, fig. 7;<br />

Blomster et al., 1998)<br />

Westkapelle, Netherl<strong>and</strong>s; R.P.T. Koeman (iv.1976)<br />

Holotype: L; Isotype: GRO (Koeman & van den Hoek, 1982)<br />

Kristineberg, Swedish west coast<br />

Holotype: LD (Bliding, 1963)<br />

North Atlantic; Gulf of Mexico; Tasmania; New Zeal<strong>and</strong><br />

Syntypes: L 13522 to 13576 (some European, mostly from Australia;<br />

Bliding, 1963)<br />

Sheerness, Kent, Engl<strong>and</strong><br />

Epitype: OXF. Lectotype: Dillenius (1742: pl. 9, fig. 6), Tremella<br />

marina fasciata (L.M. Irvine, <strong>not</strong>e dated xii 1966, in Herb. OXF)<br />

Taxonomic <strong>not</strong>es (non-type material examined)<br />

Heterotypic synonyms: <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> usneoides J. Agardh (1883)<br />

Alg. Syst. 3: 159 [misnumbered 157] (Blomster et al., 1998)<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> complanata Ku¨ tzing 1845: 248; see Silva et al. (1996)<br />

Known only from northern North I., New Zeal<strong>and</strong> (Adams, 1994)<br />

Heterotypic synonym: <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> tubulosa (Ku¨ tzing) Ku¨ tzing,<br />

based on <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> intestinalis var. tubulosa Ku¨ tzing (1845)<br />

Phycol. Germ.: 247 (Bliding, 1963)<br />

Currently treated as a synonym of <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> bulbosa (Suhr)<br />

Montagne, which can<strong>not</strong> be transferred to <strong>Ulva</strong> due to a prior<br />

homonym (see above)<br />

Type species of <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> Link (1820)<br />

Algae in Nees, Hor. Phys. Berol.: 5<br />

nom. cons. vs. Splaknon Adanson 1763, nom. rej.<br />

Differs morphologic<strong>all</strong>y <strong>and</strong> ecologic<strong>all</strong>y from E. intestinalis (Koeman<br />

& C. van den Hoek, 1982)<br />

Recorded widely from NE Atlantic <strong>and</strong> elsewhere (e.g. Coppejans,<br />

1995; Silva et al., 1996; Furnari et al., 1999)<br />

Recorded widely in Atlantic <strong>and</strong> Pacific Oceans (e.g. Silva et al.,<br />

1996; Wynne, 1998)<br />

Type material investigated by Bliding (1963) <strong>was</strong> conspecific with or<br />

closely related to <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> flexuosa (Wulfen) J. Agardh so a<br />

new name is <strong>not</strong> proposed here<br />

(continued )<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> <strong>are</strong> <strong>not</strong> <strong>distinct</strong> genera<br />

289

Table 4. (continued )<br />

Binomial in <strong>Enteromorpha</strong><br />

Basionym (if different)<br />

Binomial in <strong>Ulva</strong><br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> muscoides (Clemente) J. Cremades in J. Cremades &<br />

J.L. Pérez-Cirera (1990) Anales Jard. Bot. Madrid 47: 489.<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong> muscoides Clemente (1807) Ensayo sobre las Variedades de la<br />

Vid: 320.<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> paradoxa (C. Agardh) Ku¨ tzing (1845) Phycol. Germ.:<br />

247.<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong> paradoxa C. Agardh (1817), new name, Syn. Alg. Sc<strong>and</strong>.: XXII.<br />

Conferva paradoxa Dillwyn 1809 (illeg.)<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> procera Ahlner (1877) Bidr. <strong>Enteromorpha</strong>: 40, fig. 5.<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong> procera (Ahlner) comb. nov.<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> prolifera (O.F. Mu¨ ller) J. Agardh (1883) Alg. Syst. 3:<br />

129.<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong> prolifera O.F. Mu¨ ller (1778) Fl. Dan. 5(13): 7, pl. DCCLXIII(1)<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> pseudolinza R.P.T. Koeman & C. van den Hoek<br />

(1982) Arch. Hydrobiol. Suppl. 63 [Algol. Stud. 32]: 302, figs. 50 – 69<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong> pseudolinza (R.P.T. Koeman & C. van den Hoek) comb. nov.<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> radiata J. Agardh 1883: 156<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong> radiata (J. Agardh) comb. nov.<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> ralfsii Harvey (1851) Phycol. Brit. 3: pl. CCLXXXII<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong> ralfsii (Harvey) Le Jolis (1863) Me´ m. Soc. Imp. Sci. Nat.<br />

Cherbourg 10: 54<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> simplex (K.L. Vinogradova) R.P.T. Koeman & C. van<br />

den Hoek (1982, p. 42)<br />

E. prolifera f. simplex K.L. Vinogradova 1974, Ul’vovye Vodorosli<br />

SSSR: 99, pl. XXXIII: 5 – 12<br />

<strong>Ulva</strong> simplex (K.L. Vinogradova) comb. nov.<br />

Type locality; collector<br />

Type material (with relevant reference if any)<br />

Type or other authentic material examined<br />

Cádiz, Algeciras, Spain; Clemente<br />

Lectotype: MA-Algae 1713 (Blomster et al., 1999).<br />

Bangor, Wales<br />

Lectotype: LD 13702 (Bliding, 1960, fig. 43a – d; Womersley, 1984)<br />

Typified by the type of Conferva paradoxa Dillwyn (1809) Conf. Syn.<br />

70, suppl. pl. F.<br />

Sweden<br />

Type: S. Should be typified with material of E. procera f. denudata<br />

Ahlner Bidr. <strong>Enteromorpha</strong>: 42 (Bliding’s ‘E. ahlneriana Typus III’;<br />

Bliding, 1963)<br />

Nebbelund, Loll<strong>and</strong> Isl<strong>and</strong>, Denmark<br />

Type lost (Womersley, 1984). In the absence of material, we hereby<br />

designate by Fl. Dan. pl. DCCLXIII(1) as lectotype.<br />

Den Helder, Netherl<strong>and</strong>s; R.P.T. Koeman (vi.1975)<br />

Holotype: L<br />

Arctic Norway, Berggren<br />

Lectotype: LD 14233 (Bliding, 1963)<br />

Bangor, North Wales; J. Ralfs<br />

No types in TCD (Bliding, 1963) nor in BM. Lectotype: Harvey<br />

(1851) Phycol. Brit. 3: pl. CCLXXXII<br />

K<strong>and</strong>alakshski Zaliv, Beloye More, Murmansk Oblast, Russia; K.L.<br />

Vinogradova (8.viii.1967)<br />

Holotype: LE<br />

Taxonomic <strong>not</strong>es (non-type material examined)<br />

Heterotypic synonyms include:<br />

E. clathrata (Roth) Greville; E. crinita Nees; E. ramulosa (J.E. Smith)<br />

Carmichael (see Blomster et al., 1999)<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> welwitschii J. Agardh (1883) Alg. Syst. 3: 143. Tagus<br />

R. near Aldea, Portugal; Welwitsch, Phyc. Lusitan. 289. Syntypes:<br />

BM.<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> gelatinosa Ku¨ tzing (1849) Sp. Alg.: 482. Canary<br />

Isl<strong>and</strong>s, Despreaux. non <strong>Ulva</strong> gelatinosa Ku¨ tzing (1856) Tab. Phyc.<br />

VI, Tab. 32<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> flexuosa subsp. paradoxa (C. Agardh) Bliding (1963);<br />

recognized at species level by Womersley (1984)<br />

Heterotypic synonym:<br />

E. plumosa Ku¨ tzing (Bliding, 1963)<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> ahlneriana Bliding (1944)<br />

Bot. Not. 1944: 338, 355 is an illegitimate new name for E. procera<br />

Ahlner<br />

Heterotypic synonyms:<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> salina Ku¨ tzing 1845: 247 (Guiry & NicDonncha, 2002)<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> torta (Mertens) Reinbold (Burrows, 1991)<br />

<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> prolifera subsp. radiata (J. Agardh) Bliding (1963, p.<br />

56)<br />

Recognized in NE Atlantic: Coppejans (1995); Stegenga et al. (1997)<br />

H. S. Hayden et al.<br />

290

<strong>Ulva</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> <strong>are</strong> <strong>not</strong> <strong>distinct</strong> genera<br />

Table 5. <strong>Enteromorpha</strong> binomials that <strong>are</strong> currently regarded as synonyms of other valid names, <strong>not</strong> in current usage, <strong>and</strong>/or <strong>not</strong><br />

valid. Infraspecific taxa <strong>are</strong> omitted. Binomials indicated by an asterisk lack valid binomials in <strong>Ulva</strong>, so if they were to be<br />

recognized at the species level in this genus they would require transfer to <strong>Ulva</strong>. Binomials in p<strong>are</strong>ntheses <strong>are</strong> either <strong>not</strong> valid or<br />

<strong>not</strong> legitimate. Binomials in squ<strong>are</strong> brackets <strong>are</strong> currently placed in genera other than <strong>Enteromorpha</strong>. For taxa shown in bold,<br />

transfer to <strong>Ulva</strong> is blocked by pre-existing <strong>Ulva</strong> binomials (for details see Index Nominum Algarum)<br />

(E. adriatica Bliding)<br />

*E. africana Kützing<br />

(E. ahlneriana Bliding)<br />

E. angusta (Setchell & Gardner) M.S. Doty<br />

(E. aragoensis Bliding)<br />

*E. arctica J. Agardh<br />

E. attenuata (C. Agardh) Greville<br />

[E. aureola (C. Agardh) Kützing] a<br />

*E. basiramosa Fritsch<br />

*E. bayonnensis P.J.L. Dangeard<br />

(E. bertolonii Montagne)<br />

*E. biflagellata Bliding<br />

(E. byssoides Nees)<br />

*E. caerulescens Harvey<br />

*E. canaliculata Batters<br />

E. capillaris M. Noda<br />

[*E. chadefaudii J. Feldmann] b<br />

*E. chartacea Schiffner<br />

*E. chlorotica J. Agardh<br />

*E. clathrata (Roth) Greville (see Table 4)<br />

E. clavata Wollny<br />

[*E. coarctata Kjellman] b<br />

(E. comosa J. Agardh)<br />

*E. complanata Ku¨ tzing (see Table 4)<br />

*E. confervacea (Kützing) Kützing<br />

*E. confervicola DeNotaris<br />

(E. constricta (J. Agardh) S.M. Saifullah & M. Nizamuddin)<br />

*E. corniculata Ku¨ tzing<br />

E. cornucopiae (Lyngbye) Carmichael<br />

*E. coziana P.J.L. Dangeard<br />

*E. crinita Nees (see Table 4)<br />

E. crispa (Kützing) Kützing<br />

E. crispata (Bertoloni) Piccone<br />

*E. cruciata Collins<br />

(E. cylindracea J. Blomster)<br />

E. dangeardii H. Parriaud<br />

*E. denudata (Ahlner) Hylmö<br />

*E. echinata (Roth) Nees<br />

*E. ectocarpoidea Zanardini<br />

E. erecta (Lyngbye) Carmichael<br />

E. fascia Postels & Ruprecht (see Table 4)<br />

E. fasciculata P.J.L. Dangeard<br />

*E. firma Schiffner<br />

*E. flabellata P.J.L. Dangeard<br />

*E. fucicola (Meneghini) Kützing<br />

E. fulvescens (C. Agardh) Greville<br />

(<strong>Enteromorpha</strong> fulvescens Schiffner)<br />

(E. gayraliae P.J.L. Dangeard)<br />

E. gelatinosa Kützing (see Table 4)<br />

*E. gracillima G.S. West<br />

[E. grevillei Thuret] c<br />

[*E. groenl<strong>and</strong>ica (J. Agardh) Setchell & Gardner] a<br />

*E. gujaratensis S.R. Kale<br />

[E. gunniana J. Agardh] b<br />

(E. hendayensis P.J.L. Dangeard & H. Parriaud)<br />

*E. hirsuta Kjellman<br />

*E. hookeriana Kützing (see Table 4)<br />

E. hopkirkii M’C<strong>all</strong>a ex Harvey<br />

*E. howensis Lucas<br />

a Species of Capsosiphon (Burrows, 1991).<br />

b Species of Blidingia (Womersley, 1956, 1964; Burrows, 1991; Benhissoune et al., 2001).<br />

c Species of Monostroma (Burrows, 1991).<br />

d Species of Percursaria (Bliding, 1963).<br />

e Species of <strong>Ulva</strong> (Silva et al., 1996).<br />

*E. intermedia Bliding<br />

(E. juergensii Kützing)<br />

(E. jugoslavica Bliding)<br />

E. lanceolata (<strong>Linnaeus</strong>) Rabenhorst<br />

*E. limosa A. Parriaud<br />

E. linkiana Greville<br />

(E. linziformis Bliding)<br />

*E. littorea Ku¨ tzing<br />

E. livida W.J. Hooker<br />