Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

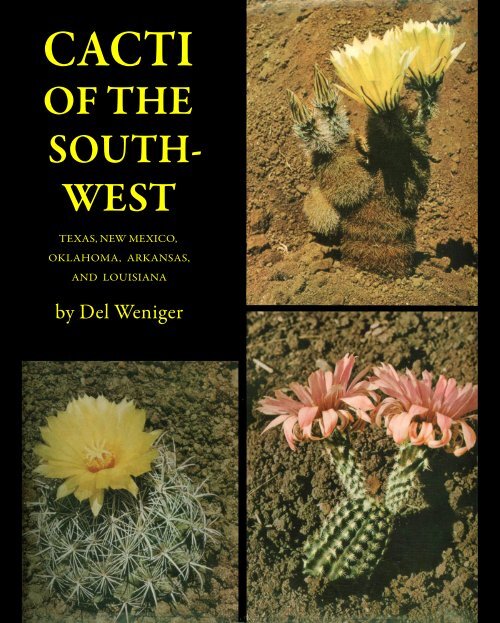

CACTI<br />

<strong>OF</strong> <strong>THE</strong><br />

<strong>SOUTH</strong>-<br />

<strong>WEST</strong><br />

TEXAS, NEW MEXICO,<br />

OKLAHOMA, ARKANSAS,<br />

AND LOUISIANA<br />

by Del Weniger

CACTI <strong>OF</strong> <strong>THE</strong> <strong>SOUTH</strong><strong>WEST</strong>

NUMBER FOUR<br />

The Elma Dill Russell Spencer Foundation Series

Echinocereus lloydii.

Cacti of the Southwest<br />

Texas, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Luosiana<br />

By D E L W E N I G E R<br />

U N I V E R S I T Y O F T E X A S P R E S S A U S T I N & L O N D O N

Standard Book Number 292–70000–8<br />

Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 78–104326<br />

All rights reserved<br />

Printed by Brüder Hartmann, Berlin, West Germany

To Ellen Schultz Quillin

CONTENTS<br />

Acknowledgments . . . . . . . . . . . . . x<br />

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . xi<br />

What Is a Cactus? . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3<br />

Key to the Genera of the Cacti . . . . . . . . . . 8<br />

Genus Echinocereus Engelmann . . . . . . . . . . 10<br />

Key to the Echinocerei, page 11<br />

Genus WTzlcoxia . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55<br />

Genus Peniocereus . . . . . . . . . . . . . 57<br />

Genus Acanthocereus . . . . . . . . . . . . 6o<br />

Genus Echinocactus . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63<br />

Key to the Echinocacti, page 65<br />

Genus Lophophora . . . . . . . . . . . . . 95<br />

Genus Ariocarpus . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100<br />

Genus Pediocactus . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103<br />

Genus Epithelantha . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107<br />

Genus Mammillaria . . . . . . . . . . . . . 110<br />

Key to the Mammillarias, page 112<br />

Genus Opuntia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 159<br />

Key to the Opuntias, page 162<br />

Glossary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 241<br />

Index of Scientific Names . . . . . . . . . . . 243<br />

Index of Common Names . . . . . . . . . . . 248

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS<br />

Support for this study was graciously provided by a grant-inaid<br />

for research from the Society of the Sigma Xi. Appreciation<br />

is expressed to Our Lady of the Lake College which granted<br />

me time for the study and made available certain facilities for<br />

growing and photographing the plants.<br />

Gratitude is also expressed to many individuals who contributed<br />

in various ways to the completion of the present study.<br />

First among them is Mrs. Roy W. Quillin (Ellen D. Schulz) who<br />

gave constant encouragement and advice and the use of books<br />

from her fine library on the Cactaceae. Dr. E. F. Castetter of the<br />

Biology Department of the University of New Mexico contributed<br />

valuable information and some specimens from New Mexico.<br />

He also arranged for the preparation and housing of my<br />

collection of important specimens gathered in this study. Numbering<br />

over seven hundred specimens of cacti, this collection is,<br />

as a result of his interest, permanently deposited in the her-<br />

barium of the University of New Mexico.<br />

The cacti of the following herbaria were studied in their entirety,<br />

thanks to the help of the staffs and especially of the persons<br />

mentioned here: the United States National Museum of the<br />

Smithsonian Institution, Dr. Jason R. Swallen and Dr. Velva<br />

Rudd being particularly helpful; the New York Botanical Garden;<br />

the Missouri Botanical Garden in St. Louis; The University<br />

of Texas; Southern Methodist University, with appreciation<br />

to Dr. Lloyd Shinners; the University of New Mexico and Dr.<br />

Castetter, as already mentioned; and the University of Colo-<br />

rado.<br />

Many others provided valuable information and aid of one<br />

kind or another. Appreciation goes to Dr. Barton H. Warnock<br />

of Sul Ross College; Drs. Claude W. Gatewood and Bruce<br />

Blauch, then of Oklahoma State University; Mr. Charles Polaski<br />

of Oklahoma City; Mr. Homer Jones and Mr. P. M. Plimmer<br />

of Alpine, Texas; Mr. Clark Champie of Anthony, New<br />

Mexico; Mr. Fred Nadolney, Mr.-Prince Pierce, and Mr. and<br />

Mrs. Earl Newhouse of Albuquerque, New Mexico; Mr. Horst<br />

Kuenzler and Mr. Dennis Cowper of Belen, New Mexico; Mr.<br />

L. J. Holland, Mr. and Mrs. S. L. Heacock, and Mrs. Ethel B.<br />

Karr, all of Colorado; Mr. and Mrs. Walter Hems of Rogers,<br />

Arkansas; Miss Lorene Martin of the Arkansas State Plant<br />

Board; Dr. T. M. Howard, Mr. Kim Kuebel, and Mr. H. C. Lawson<br />

of San Antonio, Texas; Mr. Glenn Spraker of Houston,<br />

Texas; Sr. Orton Cerna of Rosita, Coahuila, Mexico; and Sr.<br />

Romo Ruiz of Musquiz, Coahuila, Mexico.<br />

Mr. Larry Nichols and Mr. Gibbs Milliken aided the writer in<br />

making some of the photographs. The photograph of Lopho-<br />

phora williamsii var. echinata was made by Mr. David Smith.<br />

The chromatographs mentioned in the text were run by my<br />

students, Misses Vicki Perez, Rosemary Drake, and Ethel Matthews<br />

in the Biology Department of Our Lady of the Lake College.

INTRODUCTION<br />

Portrayed among the ancient stone carvings of Mexico, woven<br />

through the legends of that land, and central in the seal of the<br />

nation itself is the strange thick stem or the spiny jointed bush<br />

of the cactus. These plants must have been ever present for the<br />

people of that land, interesting to them and of some significance<br />

to their lives as far back as we can know. How strange to realize<br />

then that this fantastic group of plants had never been<br />

seen by anyone in the so-called civilized world until after<br />

Columbus discovered America. Yet this must be true; for, except<br />

for two or three small, inconspicuous, and very uncactus-like<br />

species found in places even more unknown to early travelers<br />

in the jungles of Madagascar and Ceylon, the cacti grow naturally<br />

only in the Western Hemisphere. They are as American<br />

as corn, tomatoes, tobacco, or potatoes.<br />

So they must have been seen—and felt—by the conquistadors<br />

who drove their horses across America in search of gold.<br />

No doubt these men paid little attention to the native flora as<br />

they passed, but the cacti they would have noticed for at least<br />

two reasons. How could they have failed to see the huge thickets<br />

of these devilish plants which blocked their paths to the<br />

envisioned gold and which they had to learn to respect? And<br />

when, wandering in the arid expanses, they grew hungry<br />

and had nothing else to eat, they must quickly have learned<br />

from the Indians to spot the cactus species whose fruits were<br />

succulent and sweet to the taste. We can imagine the stories they<br />

told about these outlandish plants of the New World.<br />

These accounts must have spread very rapidly, for we already<br />

have in The Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes, by John<br />

Gerarde, published in London in 1597, the descriptions and<br />

woodcut illustrations of four cacti. Gerarde names them as follows:<br />

“The Hedgehogge Thistle,” which is clearly seen from the<br />

picture to be a Melocactus from the Caribbean area, “The Torch<br />

or Thornie Euphorbium,” which is easily recognized to be a<br />

Cereus, “The Thornie Reede of Peru,” another Cereus, and “The<br />

Indian Fig Tree,” obviously a giant Opuntia. This is already<br />

an array of cacti from widely separated parts of Central and<br />

South America.<br />

Soon there followed explorers who were more directly interested<br />

in the flora of the New World. These early explorers<br />

took living specimens of the cacti home to Europe, not only<br />

because of their uniqueness, but because they would survive the<br />

long sea voyages when other plants, except in the seed stage,<br />

would not. They could even be transported all the way without<br />

the prohibitive weight of soil on their roots.<br />

Early botanists, beginning to study these plants, faced a problem.<br />

Since the plants had been totally unknown in the Old<br />

World until this time, there were no words for them at all in<br />

classical Greek or Latin. Like John Gerarde, the botanists often<br />

thought of these plants, because of their spininess, as new sorts<br />

of thistles, and so the Greek word for thistle, Kaktos, became<br />

somehow applied to them. This has become our cactus of to-<br />

day.<br />

There were soon expeditions of botanists just to study the<br />

new plants of America. An example was the Ruiz and Paron<br />

expedition of 1777 to 1787. This expedition to Peru was commissioned<br />

by the King of Spain and encompassed ten years of<br />

exploring in most difficult terrain; Spain spent upon the venture<br />

twenty million pesetas. Thousands of plant specimens were<br />

sent back, with cacti among them.<br />

The interest in these strange plants grew and soon amounted<br />

to a “cactus craze.” The extent of the “craze” is hard for us to<br />

comprehend today. By 1800 businesses were being set up by<br />

French, Belgian, and German importers to sell quantities of the<br />

plants sent by professional collectors maintained in Central and<br />

South America. Societies and wealthy enthusiasts commissioned<br />

collectors to travel to America and bring them newer and yet<br />

more strange species. Extensive collections were soon formed,<br />

grown at great pains in greenhouses. About 1830 the Duke of

xii cacti of the southwest<br />

Bedford had such a collection of cacti at Woburn Abbey. Other<br />

famous collectors in England were the Duke of Devonshire and<br />

the Reverend Mr. H. Williams of Hendon.<br />

This cultivation of the cacti must at first have been a very<br />

expensive, very genteel hobby, open only to the rich; the plants<br />

had to be expensive after having been shipped all the way from<br />

the wilds of the Western Hemisphere, and the resources necessary<br />

to keep them alive in the climate of most of Europe before<br />

the advent of gas and electric heat must have been great. The<br />

greenhouse full of cacti may well have been one of the few<br />

warmed buildings for miles around on freezing winter nights.<br />

Borg has pointed out that the cultivation of cacti has paralleled<br />

the cultivation of orchids in many ways, and this is easy to understand,<br />

since these are two of the most exotic groups of plants<br />

which can be found.<br />

But the cultivation of the cacti became the common man’s<br />

hobby much more easily than did that of the orchids. With<br />

botanical associations and importers putting out long lists of<br />

available species, cacti became cheap and available in Europe<br />

in large numbers. Soon many a humble home had at least a few<br />

of these peculiar plants in a window somewhere. We like to<br />

think of this as wonderful and of these cherished cacti as beautiful,<br />

but we must admit that even then they were not universally<br />

appreciated. Dickens, for instance, must have had an active<br />

aversion to them. While attesting to the broadness of the interest<br />

in cacti, his description of Paul Dombey’s nurse, Mrs. Pipchin,<br />

reveals his dislike for them, for he wrote of her, “Among her<br />

failings was a fondness for cactus. In the window of her parlor<br />

were half a dozen specimens writhing round bits of lath like<br />

hairy serpents.”<br />

Perhaps Dickens was sensing something cunning and insidious<br />

in these cacti, which events proved was there. They were early<br />

grown in southern Europe, and it was found that they could be<br />

grown without protection in outdoor gardens in southern Italy,<br />

Spain, Sicily, and Greece, on the Riviera, and, of course, all<br />

along the southern shore of the Mediterranean. In these areas<br />

are still today some of the finest cactus gardens in the world,<br />

with beautiful, hundred-year-old specimens to be seen.<br />

But once introduced into the Mediterranean area, certain of<br />

the Opuntias, the hardiest and most easily spread of cacti, found<br />

the hot, arid region too much to their liking and so escaped<br />

from cultivation and established themselves as permanent residents<br />

of the area. These cacti have now spread through many<br />

Mediterranean countries. Though the time required to accomplish<br />

this was actually comparatively short, man’s memory is<br />

even shorter, for so completely are they already accepted as a<br />

normal part of the flora that in many areas one finds hardly<br />

a resident who realizes that his ancestors could not have known<br />

these immigrants. Sometimes one even sees cacti in pictures and<br />

movies supposedly reconstructing the time of Christ and the<br />

Roman Empire, or in otherwise accurate portrayals of classic<br />

Greek times.<br />

In one other place cacti escaped like this and became one of<br />

the worst plant scourges ever known. This was in Australia,<br />

where several Opuntias, in the absence of their natural enemies<br />

and in an arid situation exactly to their liking, took over millions<br />

of acres and rendered them useless for anything else. Much<br />

money and effort was spent in discovering how to control these<br />

cacti in Australia, and the effort has been largely successful.<br />

They have been eliminated from huge areas and are being kept<br />

in check in others.<br />

But these two instances of cacti escaping and invading new<br />

areas are the exceptions. Usually, when taken from their natural<br />

haunts, the cacti survive only under very precise conditions<br />

and when great care is lavished upon them by their growers.<br />

Almost none of them can survive unaided even when only<br />

transplanted from one state to another within the United States.<br />

Within the Americas, where they are at home, cacti as a<br />

group are very widespread. They range from Alberta and British<br />

Columbia in Canada on the north to Patagonia, toward the<br />

tip of South America on the south. Their greatest development<br />

in both numbers and diversity is in two areas, one along the<br />

Tropic of Cancer in Mexico and the other near the Tropic of<br />

Capricorn in South America. While flourishing the most in the<br />

American deserts, they are far from restricted to these places.<br />

Special forms are found in tropical rain forests; others abound<br />

along the seashores of the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean, and<br />

the Pacific Ocean; while some thrive in mountain forests and a<br />

few are at home on bleak mountain slopes to as high as fourteen<br />

thousand feet. There are also some forms which abound on the<br />

Great Plains all the way into Canada, and within the United<br />

States it is said that indigenous cacti have been found growing<br />

in every state except Maine, Hawaii, and Alaska, although in<br />

many states they are so rare and inconspicuous that their pres-<br />

ence is unsuspected by most residents.<br />

This picture of far-ranging cacti is misleading if one thinks<br />

of any single form as so far-flung. This is the range of the group,<br />

which is a huge and diverse aggregation. It is probably fruitless<br />

to try to estimate the number of cactus forms that exist, because<br />

new publications are constantly adding new-found forms to the<br />

list, as well as realigning those already known. But it is said that<br />

there are well over three thousand known species in all. Of<br />

these, almost none range across from one America to the other.<br />

A very few species, considered broadly, may range practically<br />

across a continent, and some few cover large expanses of one or<br />

the other of the Americas, but the much more usual situation is<br />

for each species to inhabit a range measured in a few hundred<br />

square miles or less. It is very common for a species to inhabit<br />

only a certain valley or mountain range, and there are numerous<br />

forms so restricted in habitat that two or three Texas-sized<br />

ranches will contain them all.<br />

As we have seen, the cacti which excited the first interest and<br />

touched off the first cactus craze were the huge and spectacular<br />

Central and South American forms. The cacti of the United<br />

States were hardly known until later. Early botanists on the<br />

east coast of the United States found only two or three very

introduction xiii<br />

inconspicuous and uninteresting little prickly pears which they<br />

dutifully recorded and no one got excited about. As they pushed<br />

west, they found little else until they got beyond the Mississippi<br />

River. But once they began to explore the West, the study of<br />

U.S. cacti began.<br />

The first great student of U. S. cacti was the famous botanist<br />

Dr. George Engelmann. He made his headquarters at the Missouri<br />

Botanical Garden, the remarkable early botanical center<br />

in St. Louis, and studied the specimens and descriptions sent in<br />

by botanists on the early governmental surveys through the<br />

West. These botanists—such as Wislizenus, Wright, Bigelow,<br />

Parry, and Poselger—were the heroes of early cactus studies in<br />

the United States, and some of their names will be met with<br />

later, since Engelmann acknowledged his debt to them by sometimes<br />

naming cacti after them. They must have been hardy souls,<br />

riding on long treks with expeditions such as the Mexican<br />

Boundary Survey, the Pacific Railroad Survey, Pike’s expedition,<br />

and others; and one must admire their stamina, gathering<br />

cacti all day on the trail, then, while the others rested, making<br />

their records and descriptions and packing up specimens of these<br />

unpleasant-to-handle plants to send back to Engelmann. Their<br />

routes took them through the heart of the cactus country of the<br />

West, and we are amazed at the number of plants found only in<br />

places almost inaccessible even a hundred years later, which<br />

they located and recorded so long ago.<br />

Beginning in about 1846, Engelmann started publishing the<br />

results of these expeditions. He faced the herculean task of listing<br />

and describing a huge population of cacti almost unknown<br />

before to the world. He coined names for the multitude of<br />

forms, worked out something of their relationships, and presented<br />

descriptions and some of the finest botanical illustrations<br />

ever made for any plants. Although his material was sometimes<br />

incomplete and so his descriptions were sometimes deficient, he<br />

gave us the first information we have of approximately two-<br />

thirds of the U. S. cacti, information so remarkably accurate<br />

that in a few cases it has taken us almost a hundred years to<br />

verify it. Modern concepts have sometimes revised his ideas of<br />

the relationships between the forms, but almost never have we<br />

found him in error when he told where a plant grew or what it<br />

looked like.<br />

The next effort at studying the cacti of the United States was<br />

made by the great botanist John M. Coulter. In 1894 he began<br />

publishing a major work on the cacti of North America. Mostly<br />

he built on the foundation laid down by Engelmann, with the<br />

benefit of much more material collected since Engelmann’s time,<br />

but he added little really new to what was already known. It is<br />

indicative of the difficulty of studying cacti that he is said to<br />

have given up the study of this group in disgust and spent the<br />

rest of his life with other plant groups after misidentifying a<br />

cactus he had earlier named himself.<br />

About the same time as Coulter’s study, a large, general work<br />

on cacti was being produced in the German language by Karl<br />

Schumann. He did firsthand work on the cacti of the then In-<br />

dian Territory and the Canadian River area, but did not travel<br />

widely in the United States, and so his work has limited value<br />

for us today in the study of U. S. cacti.<br />

A major project on cacti was then undertaken by the Carnegie<br />

Institute. Dr. N. L. Britton and Dr. J. N. Rose, with the<br />

support of that institution, undertook to list and describe all<br />

the cacti of the world. They traveled widely throughout the<br />

Americas and visited the European collections, and as a result<br />

published a four-volume work, The Cactaceae, in 1919 to 1923.<br />

Their work had probably the greatest effect of anything ever<br />

published on the study of cacti as well as on the growing popularity<br />

of these plants. They greatly revised the classification of<br />

the group, adding a multitude of new genera and species, and<br />

their beautiful volumes, with fine color illustrations, were widely<br />

circulated, giving many people, especially in the United States,<br />

their first knowledge of the beauty of the cacti. Even today,<br />

most people still think of cacti strictly in the terms of the<br />

Britton and Rose accounts.<br />

No new attempt to encompass all of the cacti in one large<br />

study was made for many years. The task had become just too<br />

big. But the great German student of cacti, Curt Backeberg, did<br />

not flinch at the challenge, and in 1958 he brought out the first<br />

volume of a new world-wide survey, Die Cactaceae. It was<br />

completed shortly before his death and comprises six large volumes<br />

of fine descriptions, with many good pictures of the cacti<br />

of the world. It is truly a monumental work.<br />

But the great diversity of the cacti and the fact, already mentioned,<br />

that the majority of them are limited to areas which are<br />

very small (often single mountain ranges or river valleys), when<br />

set against the huge expanse covered by the group as a whole,<br />

make it very difficult for any major flora or all-inclusive cactus<br />

work to be useful on a local level. Who wants to carry the four<br />

volumes of Britton and Rose or the six of Backeberg to the Big<br />

Bend of Texas or the mountains of Peru? And if these works<br />

were to give really detailed accounts of the cacti found in all<br />

of such areas, exactly the information which the local student<br />

needs, they would become encyclopedic in size. This fact explains<br />

the numerous regional publications on cacti, both articles<br />

in journals and separate books. If one is to understand the local<br />

cacti, he must refer to these publications, done by people on the<br />

scene who have studied the larger picture and then sought out<br />

and portrayed the details of the local forms he sees about him.<br />

This book is intended to be such a regional guide.<br />

In the United States there has long been a tendency to break<br />

down the treatment of cacti into state studies. States are artificial<br />

areas and their boundaries have nothing to do with plant<br />

distribution, but it has been impossible to ignore them. The present<br />

study, however, includes the cacti of five states: Arkansas,<br />

Louisiana, Oklahoma, Texas, and New Mexico. These five states<br />

make up a unit much more logically considered, cactuswise, than<br />

any one of them alone, and a unit for whose cacti there has<br />

never been a complete guide. While lists of cactus species and<br />

some good descriptions are found in the floras of the respective

xiv cacti of the southwest<br />

states (as for instance those of Wooton and Standley for New<br />

Mexico) and many articles concerning various cacti in this region<br />

are scattered all through the literature, there has been only<br />

one complete work on cacti within this area: Texas Cacti, by<br />

Ellen D. Schulz (Mrs. Roy Quillin) and Robert Runyon. This<br />

was published in 1930, covered only the cacti of Texas, and is<br />

now out of print.<br />

The need for such a guide for these five states seems, therefore,<br />

clear. While the cacti of the far Southwest have been dealt<br />

with in numerous publications—Stockwell and Brezzeale’s Arizona<br />

Cacti of 1933, Baxter’s California Cacti of 1935, Boissevain<br />

and Davidson’s Colorado Cacti of 1940, Benson’s The<br />

Cacti of Arizona of 1950, and Earle’s Cacti of the Southwest<br />

of 1963—none of these covered more than those few forms of<br />

cacti which happened to extend their range into our area from<br />

the West. And where the cacti of this five-state area have been<br />

written about in journals or magazines it has usually been done<br />

by students who lived and worked in the far West or even in<br />

Europe, and who wrote of our cacti after brief trips through<br />

this vast area or from secondhand accounts.<br />

The cacti of this area have not lacked a detailed treatment<br />

because they were fewer in number or less diverse than those<br />

of the far Southwest. If anything, they may have presented too<br />

great a challenge just because of their number. I have found<br />

some professional botanists who believed, probably because of<br />

the greater size and conspicuousness of the Arizona species plus<br />

the greater publicity they have received, that the greatest speciation<br />

in the United States occurs in the far Southwest. Actually,<br />

this is not true. Texas alone presents more species of cacti than<br />

all of the rest of the United States combined. L. Benson lists 60<br />

cactus species in Arizona. California is said to have about 20<br />

natives; and New Mexico, about 50. On the other hand the<br />

number of separate species listed here for our five-state area is<br />

119. Earle, the most recent writer on the cacti of the Southwest,<br />

lists 121 forms, counting varieties as well as separate species for<br />

all of California, Arizona, Colorado, Utah, Nevada, and western<br />

New Mexico. Within our area we find 172 different forms.<br />

Within Texas alone can be found 106 species and 142 recognizable<br />

forms.<br />

The present work, then, lists all of the forms of cacti presently<br />

known to be growing within the five states: Arkansas, Louisiana,<br />

Oklahoma, Texas, and New Mexico. They are listed by<br />

their recognized scientific names, and immediately following<br />

(in every case where such exist) are given all of the common<br />

names which could be discovered, by which the cactus is known<br />

in various localities, including the Spanish and sometimes the<br />

Indian names. Spellings of these common names show the local<br />

variations found in the literature.<br />

A description of the whole cactus plant, not meant to be tedious<br />

but made full enough to be useful for the serious student,<br />

is then given. This description is patterned on the original one<br />

of the species, but it takes into account other descriptions by<br />

more recent students plus our own observations and so may be<br />

broader than the original in the case of quantitative characters<br />

and may add information not covered in the original.<br />

Following this is outlined the known range of natural distribution<br />

for the cactus. This is given in rather general terms, partly<br />

because there is still more to be learned about the spread of some<br />

of these plants and partly because it is not meant to be a guide<br />

telling exactly which mountain slope will provide the collector<br />

with the cactus he wants. The publication of such specific information<br />

all too often has meant that the slope is bare of any<br />

cacti at all the next year. There are no laws protecting cacti in<br />

any of the states covered in this study, and the conservation of<br />

our cacti is a real problem today. While this work gives no inaccurate<br />

or misleading information about where the various<br />

cacti are to be found, the exact locations of specific populations<br />

are not usually given. Any cactus hunter worthy of the title of<br />

“cactophile,” once given the general territory where the plant<br />

grows, might rather search out the prize himself.<br />

Next follows a discussion of each cactus listed. This is a<br />

gathering together of any remarks I might have on anything<br />

unusual or especially interesting about the cactus. Included<br />

under remarks also, because these are purely my own opinions<br />

after studying the plants and the literature upon them, are suggestions<br />

concerning its relationship to its fellows, with restatement<br />

of the specific characters which distinguish it from its<br />

closest relatives.<br />

These relationships are very complex, and the concepts of<br />

them have been almost constantly changing throughout the<br />

study of the cacti, as can be quickly traced by looking at the<br />

synonymy in almost any listing. In an attempt to avoid making<br />

this part another series of synonym lists in fine print—or a dry,<br />

dead discussion of dead names-this synonymy is presented as<br />

a historical account of the vicissitudes through which individual<br />

cactus forms, individual plant names, and the ideas of individual<br />

students went from their discovery and their first<br />

statements until the present. Such a historical approach to this<br />

material has not been made before, and it can enable us to<br />

understand much about the science of botany and about men,<br />

as well as about cacti. Of course, the material is much simplified<br />

and rendered as nontechnical as possible. Nevertheless an attempt<br />

is made to evaluate fairly, from the vantage point of the<br />

present, each important author's arguments and to assign his<br />

proposal its proper place in the history of the cactus being discussed.<br />

Lastly, each cactus form is illustrated by a full-color photograph<br />

of the plant, in most cases in bloom. A few of these<br />

photographs were made in the plant's natural location, but in<br />

most cases this proved to be impractical. Most cacti bloom only<br />

a few days out of the year, and it was obviously impossible to<br />

be in a canyon of the Texas Big Bend, on the Wichita Mountains<br />

of Oklahoma, on an Indian reservation in northwest New<br />

Mexico, and on an Ozark slope in Arkansas on precisely the<br />

days when each cactus chose to bloom. Much effort, therefore,<br />

has gone into the work of locating the various forms in the

introduction xv<br />

wild, then bringing them in and growing them in such congenial<br />

environments that they have bloomed, so that they could<br />

be pictured at the right moment. Unless otherwise stated, I<br />

made all photographs myself.<br />

The soils and backgrounds visible in the pictures are, therefore,<br />

not usually the natural environments of the plants. In fact,<br />

the colors of these have often been chosen to contrast with and<br />

make as clearly visible as possible the spines and other characters<br />

of the cacti. This means that no conclusion about the environments<br />

of these plants can be drawn from these pictures.<br />

While some readers may consider this a drawback, it should be<br />

remembered that most of these cacti use protective coloration<br />

and camouflage. Pictures of them in their natural habitats, while<br />

of value to the ecologist, usually show little detail of the plants,<br />

if they are visible at all. An extreme illustration of this difficulty<br />

would be the case of Mammillaria nellieae Croiz., where<br />

the whole plant is usually totally covered by the moss which<br />

grows with it in its rock crevice; a picture of it in loco would<br />

show only the flower apparently blooming on the moss and<br />

would be useless in illustrating what the cactus is really like.<br />

In the verbal description of the flower parts, I was confronted<br />

with the choice of employing standardized color names, such<br />

as those given in A Dictionary of Color by Maerz and Paul, or<br />

of using more general terms which would be meaningful to the<br />

average reader. I decided on the latter course in the belief that<br />

what would be gained in preciseness by the use of terms from A<br />

Dictionary of Color would be counterbalanced by the incon-<br />

venience of having to consult this reference work in a library in<br />

order to determine what was meant by the shade names used.<br />

Although as full as possible a rendering of the beauty of the<br />

flowers is an aim of these pictures, this is not their only goal. It<br />

is hoped that they may also convey a real concept of the plant<br />

body itself and of the spine character; sometimes the flower is<br />

shown at less than full angle because of this other aim.<br />

In organizing this presentation, one of the biggest problems<br />

was the delineation of the genera. The widest possible range of<br />

opinions is held today by the different authorities in the field<br />

on the limits of the genera in the Cactaceae. It seems that the<br />

present extent of the knowledge of the cacti does not enable<br />

anyone to give as definite a list of cactus genera as can be made<br />

for many other plant groups. There are several very different<br />

systems of genera, each very logical in the light of a certain set<br />

of assumptions. I have attempted to re-evaluate these in the<br />

light of the latest research available. The work of Dr. Boke at<br />

Oklahoma University and results of our own chromatographic<br />

studies seem particularly important here. The resulting alignment<br />

of the genera is in no case a new one, but in some cases<br />

favors one previous proposal and in some another.<br />

Within the genera no attempt has been made to organize the<br />

species into tribes or sections, since this sort of thing—as, for<br />

instance, various proposals for the genus Opuntia—seems still<br />

to be based on conjecture, and I find little newer and more solid<br />

evidence for any of the various contradictory proposals already<br />

made.

P L AT E S<br />

Measurements given in the photograph captions are the plant body<br />

sizes of the specific plants pictured and do not, unless otherwise stated,<br />

include flowers. In most cases this size is smaller than the maximum<br />

size achieved by the species.

Echinocereus viridiflorus var. viridiflorus. Larger plant 21/4 inches tall.<br />

Echinocereus viridiflorus var. cylindricus. 41/4 inches tall. Echinocereus viridiflorus var. standleyi. 4 inches tall.<br />

1

2<br />

Echinocereus davisii. 1 inch tall.<br />

Echinocereus chloranthus var. neocapillus. 31/2 inches tall.<br />

Echinocereus chloranthus var. chloranthus. Young plant (left):<br />

mature plant, 4 inches tall (right).<br />

Echinocereus chloranthus var. neocapillus. Immature plant (center),<br />

11/4 inches tall, flanked by mature specimens.

Echinocereus russanthus. 41/2 inches tall.<br />

(above, right)<br />

Echinocereus caespitosus var. caespitosus.<br />

The white-spined “Lace Cactus,” 3 inches tall.<br />

Echinocereus caespitosus var. caespitosus. The<br />

brown-spined “Brown-Lace Cactus,” 5 inches tall.<br />

3

4<br />

Echinocereus caespitosus var. minor. Largest stem pictured, 2 inches tall.<br />

Echinocereus caespitosus var. perbellus. 2 inches tall.

Echinocereus melanocentrus. 2 inches tall.<br />

(above, left)<br />

Echinocereus caespitosus var. purpureus.<br />

31/3 inches tall.<br />

Echinocereus fitchii.<br />

21/4 inches tall.<br />

5

Plate 6<br />

(above, left) Echinocereus baileyi.<br />

White-spined. 41/4 inches tall.<br />

(above, right) Echinocereus baileyi. Brown-spined,<br />

clustering. Largest stem pictured, 21/4 inches tall.<br />

(below) Echinocereus albispinus. Tallest stem<br />

pictured, 2 inches high.<br />

Plate 7 (opposite)<br />

(above, left) Echinocereus pectinatus var. wenigeri.<br />

Stem 41/2 inches tall.<br />

(above, right) Echinocereus pectinatus var. rigidissimus.<br />

6 inches tall.<br />

(below, left) Echinocereus chisoensis.<br />

7 inches tall.<br />

(below, right) Echinocereus pectinatus var. ctenoides (right)<br />

and Echinocereus caespitosus var. caespitosus (left).<br />

Note typical ovary and fruit coverings.

8<br />

Echinocereus pectinatus var. ctenoides. 3 inches tall.

Echinocereus dasyacanthus var. dasyacanthus.<br />

Yellow-flowered. 101/2-inch stem.<br />

Echinocereus dasyacanthus var. hildmanii. Stem 5 inch tall.<br />

Echinocereus dasyacanthus var. dasyacanthus.<br />

Pink-flowered. 12-inch stem.<br />

9

10<br />

Echinocereus roetteri. 43/4 inches tall.

Echinocereus lloydii.<br />

12 inches tall.<br />

Echinocereus triglochidiatus var. triglochidiatus.<br />

8 inches tall.<br />

11

12<br />

Echinocereus triglochidiatus var. octacanthus.<br />

Stems 41/4 inches tall.<br />

(below, left)<br />

Echinocereus triglochidiatus var. gonacanthus.<br />

4 inches tall.<br />

(below, right)<br />

Echinocereus triglochidiatus var. coccineus.<br />

61/2 inches tall.

Echinocereus coccineus var. conoides. 8 inches tall. Echinocereus polyacanthus var. rosei. 8 inches tall.<br />

Echinocereus polyacanthus var. neo-mexicanus. 41/2 inches tall.<br />

13

14<br />

Echinocereus stramineus. Clump, 30 inches in diameter. Echinocereus enneacanthus var. enneacanthus.<br />

Clustered stems, 13 inches across.<br />

Echinocereus enneacanthus var. carnosus. Tallest stem 8 inches high.

Echinocereus fendleri var. rectispinus.<br />

Tallest stem pictured, 8 inches high.<br />

(above, left)<br />

Echinocereus fendleri var. fendleri.<br />

Stem 53/4 inches tall.<br />

Echinocereus dubius. Tallest stem<br />

9 inches high. Two specimens of<br />

Lophophora williamsii in right<br />

foregrounds.<br />

15

Echinocereus papillosus var. angusticeps.<br />

Tallest stem pictured, 3 inches high.<br />

16<br />

(above, right)<br />

Echinocereus papillosus var. papillosus.<br />

Sprawling stems, 2 inches high.<br />

Echinocereus pentalophus. Stems approximately<br />

3/4 inch in diameter.

Wilcoxia poselgeri. Single<br />

upright stem, 12 inches long.<br />

Echinocereus papillosus var.<br />

papillosus on ground.<br />

(above, left)<br />

Echinocereus blanckii.<br />

Stem pictured, 101/2 inches long.<br />

Echinocereus berlandieri. Tallest<br />

stems pictured, 4 inches high.<br />

17

18<br />

Peniocereus greggii. Flowers<br />

27/8 inches in diameter.<br />

(below, left)<br />

Acanthocereus pentagonus. Flower 61/2 inches<br />

long, including ovary and tube.<br />

(below right)<br />

Echinocactus horizonthalonius var. curvispina. 6<br />

inches in diameter.

Echinocactus texensis.<br />

6 inches in diameter.<br />

(above, left)<br />

Echinocactus horizonthalonius var. moelleri.<br />

7 inches in diameter.<br />

Echinocactus asterias.<br />

21/2 inches in diameter.<br />

19

20<br />

Echinocactus uncinatus var. wrightii. 8 inches tall.<br />

(above, left)<br />

Echinocactus wislizeni.<br />

14 inches in diameter.<br />

Echinocactus whipplei.<br />

3 inches in diameter.

Echinocactus mesae-verdae.<br />

13/4 inches in diameter.<br />

(below, left)<br />

Echinocactus brevihamatus.<br />

4 inches tall.<br />

(below, right)<br />

Echinocactus scheeri.<br />

21/2 inches tall.<br />

21

22<br />

Echinocactus tobuschii.<br />

25/8 inches in diameter.<br />

(below, left)<br />

Echinocactus setispinus var. hamatus.<br />

7 inches tall.<br />

(below, right)<br />

Echinocactus setispinus var. setaceus.<br />

10 inches tall.

Echinocactus sinuatus. 5 inches diameter.<br />

Echinocactus hamatacanthus.<br />

12 inches in diameter.<br />

(below, left)<br />

Echinocactus bicolor var. schottii. 4 inches in diameter.<br />

(below, right)<br />

Echinocactus flavidispinus. 2 inches in diameter.<br />

23

24<br />

Echinocactus intertextus var. intertextus.<br />

When collected, 23/4 inches in diameter.<br />

Echinocactus intertextus var. dasyacanthus.<br />

23/4 inches in diameter.<br />

Echinocactus intertextus var. intertextus. Same plant<br />

after 1 year of cultivation. 27/8 inches in diameter.<br />

Echinocactus erectocentrus var. pallidus.<br />

21/2 inches in diameter.

Echinocactus mariposensis. Green-flowered.<br />

15/8 inches in diameter.<br />

Echinocactus conoideus. 3 inches in tall.<br />

Echinocactus mariposensis. Pink-flowered.<br />

17/8 inches in diameter.<br />

25

26<br />

Plate 26<br />

(above, left) Ariocarpus fissuratus. 35/8 inches in diameter.<br />

(above, right) Lophophora williamsii var. williamsii.<br />

Largest stem 3 inches in diameter.<br />

(below) Lophophora williamsii var. echinata.<br />

Largest stem 21/2 inches in diameter.<br />

Plate 27 (opposite)<br />

(above, left) Pediocactus simpsonii var. simpsonii. 3 inches in diameter.<br />

(above, right) Pediocactus knowltonii. 1 inch in diameter.<br />

(below, left) Pediocactus papyracanthus. 2 inches tall.<br />

(below, right) Epithelantha micromeris. 11/2 inches in diameter.

28<br />

Mammillaria scheeri. 6 inches in diameter. Mammillaria scolymoides. 31/4 inches in diameter.<br />

Mammillaria echinus. Stem 21/4 inches in diameter.<br />

Mammillaria sulcata.<br />

41/8 inches in diameter.

Mammillaria ramillosa. 31/4 inches in diameter.<br />

29

Mammillaria macromeris. Young plant,<br />

not yet clustered. 3 inches tall.<br />

(below, left)<br />

Mammillaria runyonii.<br />

4 inches in diameter.<br />

(below, right)<br />

Mammillaria similis. Typical small<br />

plant; diameter 3 inches.<br />

30

Mammillaria similis. Old plant<br />

in full bloom. Diameter 12 inches.<br />

Mammillaria vivipara var. vivipara.<br />

21/4 inches in diameter.<br />

31

Mammillaria vivipara var. arizonica. 3 inches in diameter. Mammillaria fragrans 21/4 inches in diameter.<br />

Plate 32 (opposite)<br />

(above, left) Mammillaria vivipara var. radiosa.<br />

2 inches in diameter.<br />

(above, right) Mammillaria vivipara var. neo-mexicana. Large stem<br />

21/4 inches in diameter.<br />

(below, left) Mammillaria vivipara var. borealis.<br />

2 inches in diameter.<br />

(below, right) Mammillaria vivipara var. neo-mexicana.<br />

Young plants, showing juvenile spination on sides of stem and<br />

mature spines at the tips. Larger plant 2 inches in diameter.<br />

33

34<br />

Mammillaria tuberculosa.<br />

Main stem 35/8 inches tall.<br />

Mammillaria dasyacantha. Plant<br />

pictured, 3 inches in diameter.<br />

Plate 35 (opposite)<br />

(above) Mammillaria dasyacantha and<br />

tuberculosa, growing together.<br />

(below left) Mammillaria duncanii. Showing root<br />

formation. Spiny portion of the stem 1 inch tall.<br />

(below right)<br />

Mammillaria duncanii. Same plant, with fruit,<br />

after 3 months’ cultivation.

36<br />

Mammillaria albicolumnaria. Plant pictured, 27/8 inches in diameter.

Mammillaria varicolor. Largest stem<br />

12/3 inches in diameter.<br />

(below, left)<br />

Mammillaria hesteri.<br />

4 inches tall.<br />

(below, right)<br />

Mammillaria nellieae. Blooming<br />

plant, 1 inch in diameter.<br />

37

38<br />

Mammillaria roberti. Largest stem 13/8 inches in diameter.<br />

Mammillaria sneedii. Blooming stem 3/4 inch in diameter.

(above, left)<br />

Mammillaria leei. Plants in garden cultivation.<br />

Clusters 4 to 6 inches in diameter.<br />

(above, right)<br />

Mammillaria leei. Typical root formation.<br />

Large clump, 41/4 inches across.<br />

(below, left)<br />

Mammillaria pottsii. Largest stem, 11/3 inches<br />

across. M. lasiacantha var. denudata in foreground.<br />

(below, right)<br />

Mammillaria lasiacantha var. lasiacantha.<br />

Stem 1 inch in diameter.<br />

39

40<br />

Mammillaria lasiacantha var. denudata. Stem 2 inches in diameter. Mammillaria microcarpa. 2 inches tall.<br />

Mammillaria multiceps. Cluster of stems, 41/8 inches across.

Mammillaria wrightii. Stem 13/16 inches in diameter.<br />

41

42<br />

Mammillaria wilcoxii.<br />

Stem 17/8 inches in diameter.<br />

Mammillaria heyderi var. heyderi.<br />

41/3 inches across. Mammillaria heyderi var. applanata.<br />

4 inches across.<br />

Plate 43 (opposite)<br />

(above) Mammillaria heyderi var. hemisphaerica.<br />

31/2 inches across.<br />

(below) Mammillaria meiacantha.<br />

4 inches across.

44<br />

Opuntia stricta. Plant pictured 26 inches tall.<br />

Opuntia engelmannii var. engelmannii.<br />

Pad 12 inches long.<br />

Mammillaria sphaerica. Main plant, with offsets,<br />

43/4 inches across.

Opuntia engelmannii var. texana. Largest pads pictured,<br />

8 inches wide.<br />

Opuntia engelmannii var. alta. Red-flowered.<br />

Blooming pads, 51/2 inches across.<br />

45

46<br />

Opuntia engelmannii var. alta. White-flowered.<br />

Flower 31/8 inches across.<br />

Opuntia engelmannii var. cacanapa. Largest<br />

pad shown, 7 inches across.<br />

Opuntia engelmannii var. flexispina. Main pad 101/2 inches<br />

wide. White spots are cochineal insects.

Opuntia engelmannii var. aciculata. Largest pad<br />

62/3 inches across.<br />

(above) Opuntia engelmannii var. dulcis. Largest pad<br />

8 inches in diameter. This plant grew for many years in<br />

an urn by the entrance to the Old Trail Driver’s Museum<br />

in San Antonio.<br />

Opuntia engelmannii var. subarmata.<br />

Main pad 12 inches across.<br />

47

48<br />

Opuntia engelmannii var. linguiformis.<br />

Blooming pad 16 inches long. White spots<br />

are cochineal insects.<br />

(below, left)<br />

Opuntia chlorotica. Plant about 22 inches tall.<br />

(below, right)<br />

Opuntia tardospina. 9 inches tall.

Opuntia rufida. Largest pad<br />

pictured, 7 inches long.<br />

(above, left)<br />

Opuntia spinosibacca. Largest pad<br />

pictured, 53/4 inches long.<br />

Opuntia macrocentra. Largest pad<br />

pictured, 6 inches long.<br />

49

50<br />

Opuntia gosseliniana var. santa-rita.<br />

15 inches tall.<br />

(below, left)<br />

Opuntia strigil. Largest pad pictured,<br />

73/4 inches long.<br />

(below, right)<br />

Opuntia atrispina. Largest pad pictured,<br />

6 inches across.

(above) Opuntia phaeacantha var. major. Largest pad<br />

shown, 8 inches across.<br />

(below) Opuntia phaeacantha var. nigricans. Old 6-inch<br />

pad sprawling; and new, sprouting 4-inch pads.<br />

(above, left) Opuntia leptocarpa. Shown in fruit.<br />

Plant 15 inches tall.<br />

(below, left) Opuntia leptocarpa in foreground and<br />

Opuntia engelmannii var. texana in background.<br />

51

52<br />

Opuntia phaecantha var. brunnea. Wide-open flowers, 3 inches across.

Opuntia cymochila. Largest pad pictured, 4 inches across.<br />

(above, left)<br />

Opuntia phaeacantha var. camanchica. Largest pad<br />

pictured, 41/3 inches long.<br />

Opuntia phaeacantha var. tenuispina.<br />

Pads 9 inches long.<br />

53

54<br />

Opuntia compressa var. humifusa. Largest pad<br />

pictured, 3 inches across.<br />

Opuntia compressa var. microsperma. Largest pad<br />

pictured, 3 inches long.<br />

Opuntia compressa var. macrorhiza.<br />

Pad 4 inches long, blooming.<br />

Opuntia compressa var. fusco-atra. Two specimens from the same<br />

locality. Largest pad on stunted plant, 21/4 inches long;<br />

largest pad on vigorous plant, 5 inches long.

Opuntia compressa var. fusco-atra. An abnormal form known as O. macateei.<br />

Open flower 2 inches across.<br />

Opuntia compressa var. allairei. Largest pad pictured, 61/4 inches long.<br />

Opuntia compressa var. grandiflora. Largest<br />

pad pictured, 51/4 inches long.<br />

55

56<br />

Opuntia compressa var. stenochila. Largest pad pictured, 4 inches across.<br />

Opuntia ballii. Pad<br />

21/3 inches across.<br />

Opuntia pottsii. 61/2 inches tall, exclusive of fruits. Opuntia plumbea. Pad 21/4 inches long.

Opuntia drummondii. Largest pad pictured, 3 inches long.<br />

Opuntia fragilis. Clump 61/2 inches across. Opuntia sphaerocarpa. In winter condition.<br />

Largest pad pictured, 31/4 inches across.<br />

57

58<br />

Opuntia rhodantha var. rhodantha. Yellow flowered. 61/2 inches tall. Opuntia rhodantha var. rhodantha. Pink flowered. 8 inches tall.<br />

Opuntia rhodantha var. spinosior. Larger<br />

pad pictured, 41/2 inches long.<br />

Opuntia polyacantha. Typical, heavily spined.<br />

Largest pad pictured, 4 inches long.

Opuntia polyacantha. With spines few and short.<br />

Largest pad pictured, 55/8 inches long.<br />

Opuntia hystricina. Upright pad, 4 inches long.<br />

Opuntia arenaria. Largest pad pictured 23/4 inches long. Opuntia grahamii. Pictured clump, 7 inches across.<br />

59

60<br />

Opuntia Stanlyi. Largest joint<br />

pictured, 4 inches long.<br />

(below, left)<br />

Opuntia schottii. Pictured joints,<br />

each 2 inches long.<br />

(below, right)<br />

Opuntia clavata. Largest joints pictured.<br />

11/2 inches in diameter.

Opuntia imbricata var. arborescens. Branch white ripe<br />

fruits. Main pictured. 11/4 inches in diameter.<br />

Opuntia imbricata var. viridiflora. Pictured plant 15 inches tall.<br />

(above, left)<br />

Opuntia imbricata var. arborescens. Section of the<br />

main stem pictured, 11/4 inches in diameter.<br />

(below, left)<br />

Opuntia imbricata var. vexans. Branch with ripe fruits.<br />

Largest fruit pictured, 15/8, inches in diameter.<br />

61

62<br />

Opuntia spinosior. Largest stem pictured, 1 inch in diameter. Opuntia whipplei. In winter condition, 10 inches tall.

Opuntia davisii. Largest branch<br />

pictured, 5/8 inch in diameter.<br />

Opuntia tunicata. Plant pictured,<br />

13 inches across.<br />

63

64<br />

Opuntia leptocaulis. Main stem pictured, 1/4 inch in diameter. Opuntia kleinei. Plant pictured, 4 feet tall.

CACTI <strong>OF</strong> <strong>THE</strong> SOUT<strong>WEST</strong>

What Is a Cactus?<br />

Before going directly into the description of the various<br />

cacti we might pause to consider, for those who have not concerned<br />

themselves about these things before, how a cactus differs<br />

from other plants, what is so special about it, and what are<br />

some of the problems the uniqueness of its form and physiology<br />

bring to it in its natural situation and to us if we desire to raise it.<br />

It is harder to say exactly what a cactus is and how it differs<br />

from other plants than one might think. It is obvious that a<br />

cactus is a unique plant, with special problems. Imagining how<br />

it got that way, learning how to recognize it when we see it, and<br />

understanding its adaptations to its special problems—each of<br />

these presents us with special difficulties.<br />

The origin of the cactus family remains almost completely a<br />

mystery. We are balked here by the fact that there are no fossils<br />

of any cacti. So anxious have we been for such evidence that<br />

there have been several remains grasped hopefully as being cactus<br />

fossils, but all these, such as the famous one optimistically<br />

christened Eopuntia douglassii Chaney, have since proved not<br />

to be connected with the cacti at all. The most primitive and<br />

least cactus-like forms that we know are the members of the<br />

genus Pereskia, still alive, flourishing, and all-cactus, giving us<br />

no clear clues as to how they got that way. This leaves us with<br />

only theories based on comparative anatomy studies to satisfy us.<br />

Mostly because of certain flower characteristics, it is quite<br />

often assumed that cacti are related to the Rose Family. From<br />

here one can go as far as his imagination chooses to range, presuming<br />

with some that the roses of the West Indies changed in<br />

order to adapt to more arid conditions and so gave rise to the<br />

Pereskias and through them to all cacti. This is an enchanting<br />

story, and I am sure that the cactophiles are pleased with the<br />

idea that their favorites might be descendants of the rose, but I<br />

am not so certain that the rose enthusiasts are as sympathetic to<br />

the idea of appending the cacti to their queen of the flowers.<br />

Most agree that the cacti are a young group, maybe 20,000<br />

years old, and an equally big problem is how they could have<br />

developed their extreme and fantastic adaptations in such a<br />

comparatively short time.<br />

Be that as it may, the cacti are here, and one needs to know<br />

how to recognize them. This task is complicated by the fact that<br />

most of the obvious characters by which one thinks to recognize<br />

them are shared by some plant or other somewhere in the<br />

world. This is true of such things as large, fleshy stems, vicious<br />

spines, and reduction of leaves, which to an amateur mean cactus<br />

every time. There are other plants showing all of these characteristics,<br />

some of them to almost the extent the cacti do.<br />

It is a failure to recognize this fact that accounts for the popular<br />

articles, nursery ads, and many “cactus plantings,” containing<br />

mention or actual specimens of completely unrelated plants<br />

under the banner of cactus. Although they show some at least<br />

of the above characteristics, it must be stated that such things<br />

as yuccas, agaves, century plants, sotol, and so on, are not cacti<br />

at all, but extremely modified members of the Lily Family.<br />

Ocotillo and allthorn are individual residents of the desert community<br />

showing some of the same adaptations, but belonging to<br />

other plant families. Then there is the whole multitude of African<br />

plants paralleling the cacti in almost every feature of stem,<br />

rib, spine, and leaf, but all belonging to the huge, world-wide<br />

genus Euphorbia which also includes such plants as the Poinsettia.<br />

We sometimes speak of all these other plants as succulents,<br />

setting up the categories of cacti and succulents—although<br />

the cacti are also succulent, since the word merely means<br />

“fleshy.”<br />

How then do you tell a cactus? There is no easy way to do it<br />

without close observation of details and something of a bota-

4 cacti of the southwest<br />

nist’s eye. However, a cactus is always a dicot, and its two seed<br />

leaves will distinguish it at once from all those members of the<br />

Lily Family so often called cacti, since they are monocots and<br />

have only one seed leaf.<br />

Then, a feature which all cacti have and share with no other<br />

plant is the structure called the areole. All cacti have areoles<br />

quite liberally scattered over the surface, and usually arranged<br />

in rows or spirals in the most conspicuous places. These are<br />

round to elongated spots from 1/16 to sometimes well over 1/2<br />

inch in greatest measurement; their surfaces are hard, rough,<br />

uneven, and brown or blackish or else covered with white to<br />

brown or blackish wool. These areoles are now considered to be<br />

the equivalent of complex buds, and it is from these that whatever<br />

spines the cactus possesses grow. These spines, since they<br />

come from these areoles, are always arranged in clusters, which<br />

is another feature not found on other spiny plants, whose spines<br />

are produced singly from some source other than an areole.<br />

Beyond this, for the actual features separating cacti from all<br />

other plants, one has to look to the flower. Certain rather technical<br />

features of the flower are cited, such as its having sepals<br />

and petals numerous and intergrading, its having an inferior<br />

ovary with one seed chamber and having one single style with<br />

several stigma lobes.<br />

The key to understanding why the cactus is such a strange<br />

plant is the understanding of its major problem and how it<br />

solves it. This is its water problem.<br />

Most plants are great spendthrifts when it comes to water.<br />

They stand with their roots in unfailing water supplies from<br />

streams or from moisture stored in the soil between rains; and<br />

they constantly absorb quantities of water, which they use and<br />

then pass on out through their leaves into the atmosphere. This<br />

passage of water through the typical plant is so great that we<br />

call it the transpiration stream and can best think of such plants<br />

as constantly flowing fountains of water. If there is too little<br />

water available near them such plants normally solve the problem<br />

by developing extra long roots which go where the water<br />

is, and if this fails they dry out and die.<br />

But the cactus is typically a resident of the desert or else of<br />

habitats where, for one reason or another, the water supply is<br />

practically nonexistent at least part of the time. It may be<br />

because of inadequate rainfall or because the soil is too coarse<br />

or too thin to hold much water. So the cactus has a water<br />

problem which it solves in its own way.<br />

The cactus disdains to put out the extreme root systems, often<br />

drilling fifty feet deep, used by other desert plants to find the<br />

precious water which enables them to stay alive. Instead it sits<br />

and waits for the infrequent showers which ultimately do come,<br />

even in the desert, or for the rainy season. And when moisture<br />

does come the plant is ready. Its finely branching roots absorb<br />

water rapidly when it is available, and in a short time it has<br />

taken in a large amount. But there will be another drought to<br />

come, when it may be able to take in little if any water for<br />

weeks or months, so it stores this bonanza of water to the limit<br />

of its capacity, and its adaptations for great water-storing capacity<br />

form the basis for the most obvious peculiarity of the<br />

cactus.<br />

The commonest and most simple means of storing water found<br />

in these plants is by the enlarging of the stem into a thick, fleshy<br />

column or even a round ball. A cactus adapted this way becomes<br />

literally a water-filled column or ball, actually, in large<br />

specimens, a barrel of water-from which comes the common<br />

term, “barrel cactus.” The interior of such a cactus is not a reservoir<br />

of pure water into which you could dip a ladle, as cartoons<br />

sometimes show the thirsty prospector doing, but a mass<br />

of soft tissue permeated with water. Except for the supporting<br />

framework necessary in larger species, that interior is of about<br />

the consistency of a melon’s watery pulp. When rain comes it<br />

fills to the maximum with water, and in times of drought this<br />

reserve is gradually reduced. Thus, the cactus stem swells and<br />

shrinks according to the water supply, and there is always an<br />

arrangement of ribs or tubercles which make this change in bulk<br />

possible without the whole stem alternately caving in or split-<br />

ting open.<br />

In a number of the cacti where adaptations for clambering up<br />

trees, camouflage in thickets, or something else limits the thickness<br />

or size of the stems, the root may become the water-storage<br />

organ instead. In these cacti the root may become a carrot-like<br />

taproot weighing up to fifty pounds (in the extreme case of an<br />

old Peniocereus greggii specimen) or a cluster of tubers (as<br />

found on Wilcoxia poselgeri and some of the Opuntias).<br />

The cactus, then, is a plant which solves the problem of insufficient<br />

water in its habitat by storing large amounts of water<br />

within its tissues, and this explains its succulent consistency and<br />

bloated stem. Due to this habit it is internally among the softest,<br />

most delicate of plants.<br />

But standing there as almost literally a column or barrel of<br />

water in the middle of the thirsty desert brings problems requiring<br />

still further adaptations, giving us the other remarkable<br />

characteristics of a cactus. Since the cactus may have to survive<br />

for weeks or months on the moisture it has within it, it cannot<br />

afford to be a spendthrift with water like other plants. It has<br />

to give up a little at all times to stay alive, but it must sacrifice<br />

the smallest possible amount and protect its precious store<br />

against the dryness of the desert air which would otherwise<br />

evaporate it all in a matter of hours.<br />

For this reason the leaves of a cactus are reduced or eliminated<br />

altogether. After all, leaves are for the purpose of increasing<br />

the evaporative and light-absorbing surface of the plant, and<br />

the cactus needs to reduce the evaporative surface to a minimum,<br />

while certainly, in the glaring desert, it need not spread<br />

out its surface after light. Therefore, the more strictly a desert<br />

dweller it is, the more completely the leaves tend to be reduced<br />

or absent and the green stems to take over their functions. Then,<br />

its compact form is covered with a thick, waxy epidermis which<br />

is impervious to water, and even its stomata are equipped with<br />

means to reduce moisture loss. There is great variation in the

what is a cactus? 5<br />

tenacity with which individual cacti hold water, with the most<br />

extreme desert forms said to release up to six thousand times<br />

less water in a given moment than an ordinary plant of the<br />

same weight.<br />

The thick, dry, protective covering of the cactus is so deceptive<br />

to us that we seldom think of the soft, delicate, watery interior<br />

which it protects, but we may be sure the thirsty denizens<br />

of the desert, where water is life itself, are ever conscious of it.<br />

They would eat the plant immediately just for the water, if they<br />

could get at it. So the cactus has had to add protection against<br />

all the living water-seekers which surround it, and this gives yet<br />

another of its peculiarities.<br />

The almost universal solution of the cactus to this problem is<br />

to cover itself with an armament of spines. The succulent flesh<br />

is entirely covered with a system of spines so sharp and dangerous<br />

and so perfectly spreading and interlacing that neither the<br />

browsers nor the rodents can get their teeth between them to<br />

bite into the plant. The spines are never poisonous, and one can’t<br />

ascribe maliciousness to a plant for having them. They are there<br />

as necessary protection for the otherwise most delicate, most<br />

defenseless member of the desert community. It should help one<br />

to understand the spiny thing to realize that in the desert, when<br />

an injury or a malformation leaves a space wide enough for the<br />

jaws of a rabbit or even a mouse to get between the spines and<br />

start working, the cactus is soon eaten entirely. If one goes out<br />

on the desert and cuts all of the spines off a cactus, it usually<br />

disappears overnight. Ranchers have long ago learned to profit<br />

by this fact, and in some areas, by merely burning the spines off<br />

the huge prickly pears, provide their cattle with tons of free,<br />

succulent forage. The water problem, then, is directly responsible<br />

for the soft make-up of a cactus and indirectly responsible<br />

for its hard, waxy exterior and its often unpleasant but also<br />

fascinating array of spines.<br />

The cactus faces another closely related problem. Its habitats<br />

are usually extreme in their heat and the intensity of their light.<br />

The temperature on a south-facing, rocky desert slope reaches<br />

almost unbelievable heights on a summer afternoon. Even the<br />

desert reptiles are said to avoid the sun in which the extreme<br />

desert forms of cactus have to stand all day. How can they sur-<br />

vive this baking heat and searing light?<br />

Of course many cacti could not, and these grow only in the<br />

shade of thickets or trees, but the ones which stand and take it<br />

are said to depend on their own spines for shade. The spines<br />

achieve their shading effect, somewhat after the manner of a<br />

lath-house cover, by breaking the radiation up into moving<br />

strips of endurable duration. These forms also protect the exposed<br />

surface, especially the tender growing area at the top,<br />

with a covering of wool or hair, usually white and reflective.<br />

One can fairly well judge how extreme a desert situation a<br />

species comes from and how much sun it can stand by looking<br />

at how extensively this wool is developed or how complete the<br />

spine shading is.<br />

With no tender leaves, the compact body of the cactus, with-<br />

in its spiny envelope, is thus remarkably well protected against<br />

any of the natural forces or living enemies of its habitat, and it<br />

can survive in places where only the hardiest persist. Yet it has<br />

one more major problem to surmount. It must reproduce itself.<br />

And to do this it must usually produce a flower. Some of the<br />

cacti avoid this at all but the most favorable times, and depend<br />

instead upon very well-developed vegetative reproduction, but<br />

sooner or later all have to bloom.<br />

Now, a flower is an amazingly complex structure of extremely<br />

delicate parts. Flowering is a time when the plant must<br />

open and expose for the generating touch the most precious<br />

centers of its being. It is a time of vulnerability, and not even the<br />

cactus has succeeded in armoring the flower. It may swathe the<br />

bud in spines and wool, but when the moment comes it must<br />

expose the flower to the cruel desert situation as unprotected as<br />

any rose or lily. This presents another immense problem for the<br />

cactus and its way of solving it gives us both the wonderful<br />

beauty for which the flower is famous, and the extreme fleet-<br />

ingness of the flower which exasperates us.<br />

The cactus flower is almost always renowned for its size and<br />

beauty, which are said to be for the purpose of attracting insects<br />

or other flying forms across the arid distances to pollinate<br />

it. At any rate it does not seem to be beautiful for our benefit,<br />

because the flower usually lasts so short a period and blooms at<br />

such an unfavorable time that we hardly ever catch a glimpse<br />

of it and it usually is “born to blush unseen and waste its sweet-<br />

ness on the desert air.”<br />

Most cacti have flowers which open in the worst heat of the<br />

day, usually for only a few hours, and then are closed and fading<br />

before the cool of the evening begins. It is as though the<br />

plant waits until the heat of the day drives most of its enemies<br />

under the protection of some shade to unfold these tender morsels<br />

which it cannot otherwise protect. Thus, in most forms, the<br />

flower has its brief life, the reproductive act is completed by<br />

the insects which scorn the heat, and the life spark is already<br />

down within the spiny ovary before the desert cools, so that its<br />

thirsty tribes find only wilted petals for their evening meals.<br />

Many tropical and a few of our U. S. cacti reverse this schedule<br />

entirely and open their gigantic, wonderfully fragrant flowers<br />

at night to be pollinated by night-flying insects or in a few<br />

cases by bats. In most cases these species produce their flowers<br />

on tall, spiny stems where no ordinary enemy could reach them<br />

anyway, but they fade as quickly as the others, and are usually<br />

only sadly wilted remains by dawn. Only the saguaro, whose<br />

flowers are inaccessible to almost any enemy, and some other<br />

forms protected by especially long, vicious spines seem able to<br />

enjoy the luxury of longer lasting flowers.<br />

The cactus fruit, which follows the flower, is usually protected<br />

at first by spines or wool, and grows to become a berry with<br />

numerous small seeds. In some cases this dries up and the seeds<br />

are allowed to scatter, but in many species the ripe berry becomes<br />

fleshy and at the same time loses its spines or rises out of<br />

its wool covering. Here is probably the only part of a cactus

6 cacti of the southwest<br />

purposely left unprotected. It is never poisonous, and it ranges<br />

from sour to very sweet in different species. It is snapped up<br />

and carried off by animals and birds who finally get a meal<br />

from the cactus, but who pay for it by scattering the seeds far<br />

and wide. Some of the sweetest of these fruits are relished by<br />

humans. Those of the Opuntias are called “tunas”; and the<br />

“strawberry cactus” (of which there are several species) bears<br />

this common name because the flavor of the red fruits suggests<br />

that of strawberries.<br />

In all of its stages, then, the cactus is admirably adapted for<br />

survival in an arid environment, with all of these special features<br />

accentuated to the extreme in the forms inhabiting the<br />

more severe desert regions and less markedly developed in those<br />

of less extreme situations. But these same wonderful features<br />

which make the cactus so successful in the desert bring their<br />

own problems with them, limiting it in important ways even<br />

in its natural environment and making the tough desert thing<br />

one of the most vulnerable of plants when brought out of the<br />

desert into cultivation.<br />

Its very life, we have seen, depends upon the large amount<br />

of water stored within it as watery pulp. But this brings also<br />

the greatest danger to the cactus. Everyone knows how easily<br />

bruised and how quickly rotting is the watery flesh of melons<br />

and other soft fruits. A sharp blow or a gash through the protective<br />

covering of such structures causes a breakdown of the<br />

soft tissues which often spreads like wildfire throughout, leaving<br />

the whole thing a putrid, rotten mass. This is because such<br />

soft, nutrient-filled tissues form the perfect media for the<br />

growth of bacteria and all sorts of fungi.<br />

The interior of even the toughest cactus is just as vulnerable<br />

to fungi. It survives because this tender core is surrounded by<br />

the tough, fungus-resistant epidermis. The cactus is only safe<br />

when this forms an unbroken barrier covering not only the<br />

stem but the roots of the plant. But the slightest injury, any<br />

break in this epidermis, may let in a fungus, and if one gets in<br />

before the plant can repair the break with scar tissue and starts<br />

growing in the interior, the outwardly invincible old cactus<br />

will be attacked from within. It will then be quickly permeated<br />

by the fungus and will collapse into a foul, oozing thing—often<br />

literally overnight. For this reason any injury is a greater danger<br />

to a cactus than to most plants, especially if it has been<br />

removed from the desert, where fungi are not as numerous, to<br />

a more damp climate where they abound.<br />

But the fungi often gain entrance to our cacti in a more subtle<br />

way. The epidermis on the roots of these plants is necessarily<br />

thinner than that on the stems, and it is in constant contact<br />

with the fungus-populated soil. If there is very little rainfall<br />

or the soil is open and fast-draining, all will probably be well,<br />

but if there are periods of continuous rainfall, or if the soil is<br />

close-packed and remains for any time water-saturated, then<br />

the normally hard, dry, and impervious epidermis of the roots<br />

becomes wet through and softened, and loses its impermeability<br />

to the fungi. The defense barrier is dissolved, and almost any<br />

cactus whose roots lie in waterlogged soil for over twenty-four<br />

hours or so will be invaded and reduced in about that much<br />

longer to stinking carrion. This is the fate of most cacti taken<br />

in from the desert and planted in heavy yard soil in a more<br />

rainy region or else in a pot which is watered every day along<br />