Biological Society of Washington - Department of Botany ...

Biological Society of Washington - Department of Botany ...

Biological Society of Washington - Department of Botany ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

BULLETIN <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>Biological</strong> <strong>Society</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Washington</strong><br />

ISSN 0097-0298<br />

checklist <strong>of</strong> freshwater fishes <strong>of</strong> the guiana shield<br />

10 September 2009<br />

NUMBER 17

Bulletin Editor: Stephen L. Gardiner<br />

Review Editor: Bruce B. Collette<br />

Copies available as the supply lasts from:<br />

The Custodian <strong>of</strong> Publications<br />

<strong>Biological</strong> <strong>Society</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Washington</strong><br />

MRC 116<br />

National Museum <strong>of</strong> Natural History<br />

P.O. Box 37012<br />

<strong>Washington</strong>, D.C. 20013-7012<br />

(Cost $20.00, including postage and handling)<br />

© <strong>Biological</strong> <strong>Society</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Washington</strong>, 2009

CHECKLIST OF THE FRESHWATER FISHES OF THE<br />

GUIANA SHIELD<br />

Richard P. Vari, Carl J. Ferraris, Jr., Aleksandar Radosavljevic, and Vicki A. Funk<br />

i

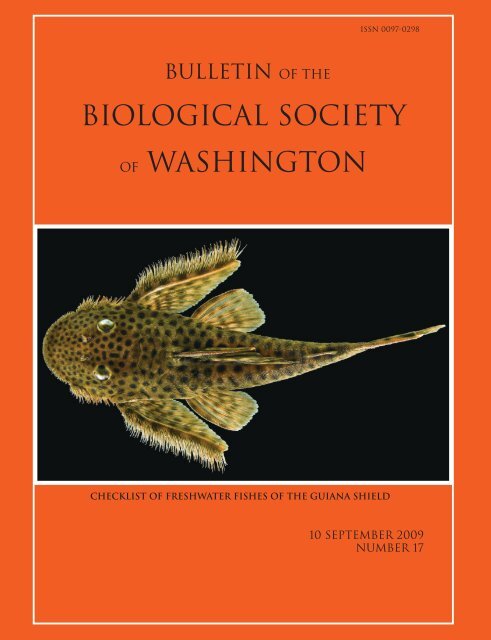

Front cover illustration: Pseudolithoxus dumus, family Loricariidae (see Plate 12, Figure G).<br />

Illustrations facing each section:<br />

For the Introduction, montage <strong>of</strong> radiographs <strong>of</strong> fishes from the rivers <strong>of</strong> the Guiana Shield, upper left –<br />

Rhaphiodon vulpinis, Cynodontidae; upper right – Prochilodus mariae, Prochilodontidae; center – Serrasalmus<br />

irritans, Characidae, Serrasalminae; lower left – Corydoras filamentosus, Callichthyidae; and lower right,<br />

Sternarchorhynchus roseni, Apteronotidae, mature male with enlarged dentary dentition. Images and plate<br />

prepared by S. Raredon.<br />

For the Fishes <strong>of</strong> the Guiana Shield, Acnodon oligocanthus (Serrasalminae, juvenile) from Steindachner, F. 1915.<br />

Denkschriften der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen<br />

Classe, Wien 93:15–105 (date based on release <strong>of</strong> separates <strong>of</strong> main work published in 1917).<br />

For the Guide to the Checklist, Acroronia nassa (Cichlidae) from Steindachner, F. 1875. Sitzungsberichte der<br />

Akademie der Wissenschaften, Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Classe, Wien 71:61–137.<br />

For the Photographic Atlas <strong>of</strong> Fishes <strong>of</strong> the Guiana Shield, Leptodoras hasemani (Doradidae) from Steindachner,<br />

F. 1915. Denkschriften der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen<br />

Classe, Wien 93:15–105 (date based on release <strong>of</strong> separates <strong>of</strong> main work published in 1917).<br />

Preferred citations:<br />

Vari, R. P., C. J. Ferraris, Jr., A. Radosavljevic, & V. A. Funk, eds., 2009. Checklist <strong>of</strong> the freshwater fishes <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Guiana Shield.—Bulletin <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Biological</strong> <strong>Society</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Washington</strong>, no. 17.<br />

or, e.g.,<br />

Vari, R. P., & C. J. Ferraris, Jr. 2009. Fishes <strong>of</strong> the Guiana Shield. In Vari, R. P., C. J. Ferraris, Jr., A.<br />

Radosavljevic, & V. A. Funk, eds., 2009. Checklist <strong>of</strong> the freshwater fishes <strong>of</strong> the Guiana Shield.—Bulletin <strong>of</strong><br />

the <strong>Biological</strong> <strong>Society</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Washington</strong>, no. 17.<br />

ii

CONTENTS<br />

CONTRIBUTORS. . . ......................................................... iv<br />

ABSTRACT . . . ............................................................. vii<br />

INTRODUCTION. . . .........................................................<br />

Vicki A. Funk and Carol L. Kell<strong>of</strong>f<br />

1<br />

FISHES OF THE GUIANA SHIELD. .............................................<br />

Richard P. Vari and Carl J. Ferraris, Jr.<br />

9<br />

GUIDE TO THE CHECKLIST . .................................................<br />

Aleksandar Radosavljevic<br />

21<br />

CHECKLIST. . . ............................................................. 25<br />

Pristiformes . ............................................................. 25<br />

Mylobatiformes . . ......................................................... 25<br />

Osteoglossiformes. ......................................................... 25<br />

Anguilliformes . . . ......................................................... 25<br />

Clupeiformes ............................................................. 25<br />

Characiformes . . . ......................................................... 25<br />

Siluriformes . ............................................................. 36<br />

Gymnotiformes . . ......................................................... 45<br />

Cyprinodontiformes . . . ..................................................... 47<br />

Beloniformes ............................................................. 48<br />

Synbranchiformes. ......................................................... 48<br />

Perciformes . ............................................................. 48<br />

Pleuronectiformes. ......................................................... 51<br />

Tetraodontiformes ......................................................... 51<br />

Lepidosireniformes ......................................................... 51<br />

PHOTOGRAPHIC ATLAS OF FISHES OF THE GUIANA SHIELD. .....................<br />

Mark Sabaj Pérez<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

53<br />

APPENDIX: PLATES ..................................................... 61<br />

INDEX TO ORDERS, FAMILIES, AND SUBFAMILIES . ............................. 95<br />

iii

CONTRIBUTORS<br />

James S. Albert, <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> Biology, University <strong>of</strong> Louisiana at Lafayette, Lafayette, Louisiana 70504-2451,<br />

U.S.A., e-mail: jxa4003@louisiana.edu<br />

Jonathan W. Armbruster, <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Biological</strong> Sciences, 331 Funchess, Auburn University, Alabama 36849,<br />

U.S.A., e-mail: armbrjw@auburn.edu<br />

Paulo A. Buckup, Departamento de Vertebrados, Museu Nacional, Quinta da Boa Vista, 20940-040 Rio de<br />

Janeiro, RJ, Brazil, e-mail: buckup@acd.ufrj.br<br />

Ricardo Campos-da-Paz, Escola de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Av.<br />

Pasteur, 458/sala 408, Urca - Rio de Janeiro, RJ, 22290-240, Brazil, e-mail: rcpaz@acd.ufrj.br<br />

Marcelo R. de Carvalho, Instituto de Biociências, Universidade de Sâo Paulo, Rua do Matão, Trav. 14, no. 101,<br />

São Paulo, SP, 05508-900, Brazil, e-mail: mrcarvalho@ib.usp.br<br />

Lilian Cassati, Laboratório de Ictiologia, Departamento de Zoologia e Botânica, IBILCE-UNESP, Rua Cristóvão<br />

Colombo, 2265, São José do Rio Preto, SP, 15054-000, Brazil, e-mail: licasatti@hotmail.com<br />

Ning Labbish Chao, Universidade Federal do Amazonas, Caixa Postal 3695, Manaus, AM 69051-970, Brazil,<br />

e-mail: piabas@gmail.com<br />

Bruce B. Collette, National Marine Fisheries Service, Systematics Laboratory MRC 153, National Museum <strong>of</strong><br />

Natural History, <strong>Washington</strong> D.C. 20560-0153, U.S.A., e-mail: collettb@si.edu<br />

Wilson J. E. M. Costa, Laboratório de Ictiologia Geral e Aplicada, Departamento de Zoologia -- UFRJ, Caixa<br />

Postal 68049, 21944-970 Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil, e-mail: wcosta@acd.ufrj.br<br />

Fabio di Dario, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Av. São José do Barreto, São José do Barreto, Caixa<br />

Postal 119331, Macae, RJ, 27921-550, Brazil, e-mail: didario@gmail.com<br />

Carl J. Ferraris, Jr., 2944 NE Couch St., Portland, OR 97232, USA; and Division <strong>of</strong> Fishes, National Museum <strong>of</strong><br />

Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, <strong>Washington</strong>, D.C. 20560-0159, U.S.A., e-mail: carlferraris@comcast.net<br />

John P. Friel, Museum <strong>of</strong> Vertebrates, Cornell University, E151 Corson Hall, Ithaca, New York 14853-2701,<br />

U.S.A., e-mail: jpf19@cornell.edu<br />

Vicki A. Funk, <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Botany</strong>, National Museum <strong>of</strong> Natural History, Smithsonian Institution,<br />

<strong>Washington</strong>, D.C. 20560-0166, U.S.A., e-mail: funkv@si.edu<br />

Michel Jégu, Antenne IRD, UR 131, Laboratoire d’Ichtyologie, M.N.H.N., 43 rue Cuvier, 75231 Paris Cedex 05,<br />

France, e-mail: jegu@mnhn.fr<br />

Carol L. Kell<strong>of</strong>f, <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Botany</strong>, National Museum <strong>of</strong> Natural History, Smithsonian Institution,<br />

<strong>Washington</strong>, D.C. 20560-0166, U.S.A., e-mail: kell<strong>of</strong>fc@si.edu<br />

Sven O. Kullander, <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> Vertebrate Zoology, Swedish Museum <strong>of</strong> Natural History, P. O. Box 50007, SE-<br />

104 05 Stockholm, Sweden, e-mail: sven.kullander@nrm.se<br />

Francisco Langeani Neto, Laboratório de Ictiologia, Departamento de Zoologia e Botânica, IBILCE-UNESP, Rua<br />

Cristóvão Colombo, 2265, São José do Rio Preto, SP, 15054-000, Brazil, e-mail: langeani@zoo.ibilce.unesp.br<br />

Flávio C. T. Lima, Museu de Zoologia, Universidade de São Paulo, Caixa Postal 42594, São Paulo, SP, 04299-970,<br />

Brazil, e-mail: fctlima@usp.br<br />

Rosana S. Lima, Universidade de Estado de Rio de Janeiro, Faculdade de Formação de Pr<strong>of</strong>essores, Rua Dr.<br />

Francisco Portela, 794, São Gonçalo, RJ, 24435-000, Brazil, e-mail: rosanasl@yahoo.com.br<br />

Carlos A. S. Lucena, Laboratory <strong>of</strong> Ichthyology, Museu de Ciências e Tecnologia PUCRS, Caixa Postal 1429,<br />

Porto Alegre, RS, 90619-900, Brazil, e-mail: lucena@pucrs.br<br />

iv

Paulo H. F. Lucinda, Laboratório de Ictiologia, Universidade do Tocantins - Campus de Porto Nacional Caixa<br />

Postal 25, Porto Nacional, TO, 77500-000, Brazil, e-mail: plucinda@unitins.br<br />

John G. Lundberg, The Academy <strong>of</strong> Natural Sciences, <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ichthyology, 1900 Benjamin Franklin<br />

Parkway, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19103, U.S.A., e-mail: lundberg@acnatsci.org<br />

Luiz R. Malabarba, Departamento de Zoologia -- IB, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Av. Bento<br />

Gonçalves, 9500 - bloco IV - Prédio 43435, Porto Alegre, RS, 91501-970, Brazil, e-mail: malabarb@ufrgs.br<br />

John D. McEachran, <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> Wildlife & Fishery Science, Texas A&M University, 22587 AMU, College<br />

Station, Texas 77843-2258, U.S.A., e-mail: jmceachran@tamu.edu<br />

Naércio A. Menezes, Museu de Zoologia, Universidade de São Paulo, Caixa Postal 42594, São Paulo, SP, 04299-<br />

970, Brazil, e-mail: naercio@usp.br<br />

Cristiano Moreira, Departamento de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Rua Pr<strong>of</strong>. Artur<br />

Riedel, 275, Diadema, SP, 09972-270, Brazil, e-mail: Moreira.c.r@gmail.com<br />

Carla S. Pavanelli, Fundação Universidade Estadual de Maringá, Nupelia, Av. Colombo, 3690, Maringá, PR,<br />

87020-900, Brazil, e-mail: carlasp@nupelia.uem.br<br />

Aleksandar Radosavljevic, The City College <strong>of</strong> New York, 526 Marshal Science Building, 160 Convent Avenue,<br />

New York, New York 10031, U.S.A., e-mail: alex.radosavljevic@gmail.com<br />

Robson T. C. Ramos, Depto de Sistemática e Ecologia, Universidade Federal da Paraíba, PB, João Pessoa, 58059-<br />

900, Brazil, e-mail: robtamar@dse.ufpb.br<br />

Roberto E. Reis, Laboratory <strong>of</strong> Ichthyology, Museu de Ciências e Tecnologia PUCRS, Caixa Postal 1429, Porto<br />

Alegre, RS, 90619-900, Brazil, e-mail: reis@pucrs.br<br />

Ricardo S. Rosa, Depto de Sistemática e Ecologia, Universidade Federal da Paraíba, João Pessoa, PB, 58059-900,<br />

Brazil, e-mail: rsrosa@dse.ufpb.br<br />

Mark Sabaj Pérez, The Academy <strong>of</strong> Natural Sciences, <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ichthyology, 1900 Benjamin Franklin<br />

Parkway, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19103, U.S.A., e-mail: sabaj@acnatsci.org<br />

Scott A. Schaefer, Division <strong>of</strong> Vertebrate Zoology, American Museum <strong>of</strong> Natural History, Central Park West at<br />

79th Street, New York, New York 10024-5192, U.S.A., e-mail: schaefer@amnh.org<br />

Oscar A. Shibatta, Departamento de Biologia Animal e Vegetal, Centro de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade<br />

Estadual de Londrina, 86051-990 Londrina, PR, Brazil, e-mail: shibatta@uel.br<br />

Mônica Toledo-Piza, Departamento de Zoologia, Instituto de Biociências, Universidade de São Paulo, Caixa<br />

Postal 11461, 05422-970 São Paulo, SP, Brazil, e-mail: mtpiza@usp.br<br />

Richard P. Vari, Division <strong>of</strong> Fishes, National Museum <strong>of</strong> Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, <strong>Washington</strong>,<br />

D.C. 20560-0159, U.S.A., e-mail: varir@si.edu<br />

Claude Weber, <strong>Department</strong> d’Herpetologie et d’Ichtyologie, Museum d’Histoire Naturelle, P. O. Box 434, CH-<br />

1211 Genève, Switzerland, e-mail: claude.weber@mhn.ville-ge.ch<br />

Marilyn Weitzman, Division <strong>of</strong> Fishes, National Museum <strong>of</strong> Natural History, Smithsonian Institution,<br />

<strong>Washington</strong>, D.C. 20560-0159, U.S.A., e-mail: weitzmam@si.edu<br />

Stanley H. Weitzman, Division <strong>of</strong> Fishes, National Museum <strong>of</strong> Natural History, Smithsonian Institution,<br />

<strong>Washington</strong>, D.C. 20560-0159, U.S.A., e-mail: weitzmas@si.edu<br />

Wolmar Wosiacki, Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, Laboratório de Ictiologia, Av. Magalhães Barata 376 Caixa<br />

Postal Box 399, Belém, PA, 66040-170, Brazil, e-mail: wolmar@museu-goeldi.br<br />

Angela M. Zanata, Departamento de Zoologia, Universidad Federal da Bahia, Rua Barão de Geremoabo, Campus<br />

de Ondina, Salvador, BA, 40170-290, Brazil, e-mail: a_zanata@yahoo.com.br<br />

v

Abstract.—Distributions are provided for 1168 species <strong>of</strong> fishes that live in the<br />

freshwater drainage systems overlying the Guiana Shield in Brazil, Colombia,<br />

French Guiana, Guyana, and Suriname. This total includes representatives <strong>of</strong><br />

376 genera, 49 families, and 15 orders, with five orders (Characiformes,<br />

Siluriformes, Perciformes, Gymnotiformes, and Cyprinodontiformes) accounting<br />

for 96.7% <strong>of</strong> the diversity. Drainage systems on the Guiana Shield are home<br />

to approximately 23% <strong>of</strong> the freshwater species known from Central and South<br />

America. A summary is provided <strong>of</strong> ichthyological collecting on the Shield along<br />

with summaries <strong>of</strong> major publications dealing with fishes <strong>of</strong> each region on the<br />

Shield. Factors that may account for the high species level diversity in that<br />

region are discussed. Methods for photographing fishes are detailed, and a<br />

photographic album <strong>of</strong> 127 species <strong>of</strong> 46 families that occur on the Shield is<br />

included.<br />

Key Words.—Guiana Shield Fishes, Freshwaters, Brazil, Colombia, French<br />

Guiana, Guyana, Suriname, Venezuela.<br />

vii

In the face <strong>of</strong> the growing biodiversity crisis, we must<br />

move to document and evaluate the biota <strong>of</strong> our<br />

natural areas. As taxonomists, it is part <strong>of</strong> our job to<br />

name, place into groups, and keep track <strong>of</strong> the species<br />

that we study. Often we use the distribution <strong>of</strong> the taxa<br />

to help with our work and to provide a broader context<br />

for the results. In doing this job, taxonomists produce<br />

checklists, floras and faunas, and monographs. In fact,<br />

collecting specimens and producing these documents<br />

are essential elements in our quest to understand the<br />

natural world and how it evolved. Checklists are the<br />

‘‘first pass’’ in our attempts to understand the diversity<br />

<strong>of</strong> an area. They give us the first approximation <strong>of</strong> the<br />

known diversity <strong>of</strong> any group or groups <strong>of</strong> organisms<br />

and they <strong>of</strong>ten provide the first pr<strong>of</strong>ile <strong>of</strong> the biodiversity<br />

in relatively poorly known parts <strong>of</strong> the globe. For<br />

many groups, they may represent the most complete<br />

information available and since basic taxonomic data<br />

provide the essential information for studies in systematic<br />

and evolutionary biology, we continually seek<br />

to improve and update it. Checklists have many uses:<br />

they are aids in the identification and correct naming <strong>of</strong><br />

species, they serve as essential resources for biodiversity<br />

estimates and biogeographic studies, and they are<br />

starting points for more detailed studies <strong>of</strong> an area’s<br />

biota. When reviewed by many specialists, they <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

represent the most advanced state <strong>of</strong> knowledge available<br />

in the field. But they do more than that, beyond<br />

these basics they increase our knowledge <strong>of</strong> this fascinating<br />

region and act as a starting point for additional<br />

biodiversity research because they give insight into the<br />

species richness, endemicity, and floral and faunal<br />

affinities for the region and provide the baseline<br />

information for analyzing species turnover rates and<br />

migration or invasion events and many other biological<br />

phenomena (e.g., Funk & Richardson 2002, Funk et al.<br />

2002, 2005; Ferrier et al. 2004, Kell<strong>of</strong>f & Funk 2004).<br />

Checklists also increase national and regional pride by<br />

demonstrating the diversity <strong>of</strong> the area and provide<br />

important public outreach and fundamental information<br />

to be used by governments and conservation<br />

organizations in addressing the biodiversity crisis. This<br />

Checklist <strong>of</strong> the Fishes <strong>of</strong> the Guiana Shield, when<br />

combined with the recently published Checklist <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Terrestrial Vertebrates <strong>of</strong> the Guiana Shield (Hollowell<br />

& Reynolds 2005), and Checklist <strong>of</strong> the Plants <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Guiana Shield (Funk et al. 2007), provides a sound<br />

basis for future research and conservation efforts.<br />

This Checklist <strong>of</strong> the Fishes <strong>of</strong> the Guiana Shield is an<br />

excellent example <strong>of</strong> effective interaction, involving<br />

ichthyologists from around the world who contributed<br />

in diverse ways to its completion. It began as an<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

V. A. FUNK and CAROL L. KELLOFF<br />

extraction from Reis et al. (2003) but quickly grew into<br />

a larger and more involved project. As with any<br />

endeavor <strong>of</strong> this type, insights that specialists have<br />

gained through their experience are irreplaceable in<br />

correcting errors and updating classifications. In order<br />

to make future editions <strong>of</strong> this checklist as current and<br />

accurate as possible, specialists are encouraged to<br />

contact the Smithsonian’s <strong>Biological</strong> Diversity <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Guiana Shield Program with additions or corrections.<br />

The Guiana Shield<br />

The Guiana Shield region is a biologically rich area<br />

that includes much <strong>of</strong> northeastern South America<br />

(Fig. 1). It is strictly defined by the underlying<br />

geological formation known as the Guiana Shield,<br />

and in the context <strong>of</strong> this volume the term Guiana<br />

Shield also refers to the corresponding geographic<br />

region. That region includes the Venezuelan states <strong>of</strong><br />

Bolívar and Amazonas, and a portion <strong>of</strong> Delta<br />

Amaçuro; all <strong>of</strong> Guyana, Suriname, and French<br />

Guiana; and parts <strong>of</strong> northern Brazil. Several geological<br />

outliers <strong>of</strong> the Guiana Shield occur west <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Orinoco River in Colombia. In Spanish and Portuguese<br />

speaking countries, the region is <strong>of</strong>ten referred to<br />

as the ‘‘Guayana’’; thus the terms Colombian<br />

Guayana, Brazilian Guayana, and Venezuelan<br />

Guayana are <strong>of</strong>ten used. The total area <strong>of</strong> the Guiana<br />

Shield is approximately 1,520,000 km 2 . Table 1 lists the<br />

square kilometers <strong>of</strong> political divisions that occur<br />

within the region. See Berry et al. (1995) for a review<br />

<strong>of</strong> definitions <strong>of</strong> and terminology related to the Guiana<br />

Shield region.<br />

Geology<br />

The Guiana Shield (Fig. 1) is a distinct geologic<br />

region that underlies Guyana, Suriname, French<br />

Guiana, parts <strong>of</strong> Venezuela, and Brazil, and a small<br />

area in Colombia. It is roughly bounded by the<br />

Atlantic Ocean to the north and east, the Orinoco<br />

River to the north and west, the Río Negro (a major<br />

tributary <strong>of</strong> the Amazon River) to the southwest, and<br />

the Amazon River to the south (Gibbs & Barron 1993).<br />

The Guiana Shield is a distinct ancient geological<br />

formation that includes the mountain systems that<br />

form the watershed boundary between the Amazon<br />

and Orinoco rivers. On the Shield’s western side, the<br />

Orinoco River and Río Negro are connected by the<br />

Río Casiquiare, making most <strong>of</strong> the region somewhat<br />

like an island; however, there are some areas <strong>of</strong> nearby<br />

Colombia that have remnants <strong>of</strong> the Shield formation.<br />

The southern boundary <strong>of</strong> the Guiana Shield is

2 BULLETIN OF THE BIOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF WASHINGTON<br />

Figure 1. The Guiana Shield; adapted from Gibbs & Barron (1993), with the region <strong>of</strong> western outliers indicated.<br />

difficult to define precisely, as a broad band <strong>of</strong> outwash<br />

materials resulting from erosion occurs between<br />

mountains on the southern boundary <strong>of</strong> the Shield<br />

and the Amazon and Negro rivers stretching into parts<br />

<strong>of</strong> northern Brazil. Also, much <strong>of</strong> the Venezuelan state<br />

<strong>of</strong> Delta Amacuro occurs over thick sediments<br />

deposited primarily by the Orinoco River and is really<br />

not strictly part <strong>of</strong> the Shield; however, some mountains<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Guiana Shield occur in this state’s southern<br />

section, and a large proportion <strong>of</strong> the sediments <strong>of</strong> the<br />

delta are derived from outwash from the highlands <strong>of</strong><br />

the Shield. For more detailed discussions <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Table 1.—Divisions <strong>of</strong> the Guiana Shield in approximately west to<br />

east arrangement, with abbreviations used and estimated areas.<br />

Division Abbr. Area (km 2 )<br />

*Colombian Guayana CG 120,325<br />

Amazonas, Venezuela VA 175,750<br />

Bolívar, Venenzuela BO 238,000<br />

*Delta Amacuro, Venezuela DA 40,200<br />

*Amazonas, Brazil BA 125,550<br />

*Roraima, Brazil RO 173,750<br />

*Pará, Brazil PA 243,280<br />

*Amapá, Brazil AP 98,750<br />

Guyana GU 214,970<br />

Suriname SU 163,270<br />

French Guiana FG 91,000<br />

Total (km 2 ) 1,896,845<br />

*5 not all parts <strong>of</strong> these politically defined areas are included in<br />

the Guiana Shield region.<br />

geology <strong>of</strong> the area, readers should refer to Gibbs &<br />

Barron (1993) and Huber (1995a).<br />

The base <strong>of</strong> the Guiana Shield is composed <strong>of</strong><br />

crystalline rocks <strong>of</strong> Proterozoic origin; these are mainly<br />

granites and gneisses formed between 3.6 and 0.8<br />

billion years ago (Mendoza 1977, Schubert & Huber<br />

1990). Large areas <strong>of</strong> the Shield were overlain with<br />

sediments from 1.6 to 1 billion years ago and cemented<br />

during thermal events (Huber 1995a). These quartzite<br />

and sandstone rocks comprise the Roraima formation<br />

and today remnants are scattered across the central<br />

portion <strong>of</strong> the Shield extending west from the Potaro<br />

Plateau <strong>of</strong> the Pakaraima Mountains in central<br />

Guyana through parts <strong>of</strong> Venezuela and Colombia<br />

(Arbeláez & Callejas 1999) and south into northern<br />

Brazil (Leechman 1913, Gibbs & Barron 1993). Within<br />

this area, erosion has resulted in numerous verticalwalled,<br />

frequently flat-topped mountains called ‘‘tepuis,’’<br />

among them are Chimantí-tepui (2550 m), Cerro<br />

Duida (2358 m), and Auyán-tepui (2450 m). Pico de<br />

Neblina (3014 m) is the Shield’s western-most tepui<br />

and highest point, located on the southern-most<br />

segment <strong>of</strong> the border between Venezuela and Brazil.<br />

Mount Roraima (2810 m) is located at the juncture <strong>of</strong><br />

Guyana, Venezuela, and Brazil and includes the<br />

highest point within Guyana. The eastern-most peaks<br />

in Guyana reach approximately 2000 m elevation,<br />

including Mt. Ayanganna (2041 m). Several <strong>of</strong> these<br />

mesa-like formations are virtually inaccessible by foot

NUMBER 17 3<br />

and are so unusual that they inspired a fictional<br />

scientific expedition referred to one as ‘‘The Lost<br />

World’’ (Doyle 1912), a term sometimes applied to all<br />

tepuis. Notable waterfalls <strong>of</strong> the region include Angel<br />

Falls (979 m) on Auyán-tepui in Venezuela and<br />

Kaieteur Falls (226 m), which flows year around, on<br />

the eastern-most edge <strong>of</strong> the Roraima formation<br />

known as the Potaro Plateau in Guyana.<br />

Granitic dome mountains occur on the Shield in the<br />

southern part <strong>of</strong> the three Guianas (Guyana, Suriname,<br />

French Guiana), where they are known as<br />

‘‘inselbergs,’’ as well as in the western extreme <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Shield in the Puerto Ayacucho region in Venezuela<br />

where they are called ‘‘lajas.’’ Deposits <strong>of</strong> low-nutrient<br />

white sands occur inland <strong>of</strong> the coastal plain, in belts<br />

across the Shield, and in isolated pockets. Large areas<br />

<strong>of</strong> savanna are found in the region, particularly the<br />

complex <strong>of</strong> savannas that includes the Rupununi<br />

Savanna in southwestern Guyana, the Gran Sabana<br />

in eastern Venezuela, and the savannas <strong>of</strong> northern<br />

Roraima, Brazil. In some <strong>of</strong> these areas the sands<br />

overlay a clay hardpan that is resistant to penetration<br />

by tree roots and that floods during the heavy rainy<br />

season, resulting in limited forest growth. Tertiary and<br />

Quaternary sediments separate the southern edge <strong>of</strong><br />

the Guiana Shield from the Amazon River and the<br />

eastern edge from the Atlantic Ocean.<br />

Climate<br />

As a whole, the Guiana Shield region has a tropical<br />

climate characterized by a relatively high mean annual<br />

temperature exceeding 25uC at sea level, an annual<br />

monthly maximum temperature range <strong>of</strong> less than 5uC,<br />

and an average daily temperature range <strong>of</strong> approximately<br />

6uC (Snow 1976). Because <strong>of</strong> the Guiana<br />

Shield’s location just north <strong>of</strong> the equator, its climate<br />

varies primarily according to elevation and effects <strong>of</strong><br />

the trade winds that combine to affect rainfall patterns.<br />

The trade winds blow consistently from the east and<br />

northeast, <strong>of</strong>f <strong>of</strong> the Atlantic Ocean onto northeastern<br />

South America, with wind speeds averaging from 3–4<br />

m per second. Due to orographic effects, the easternmost<br />

escarpments <strong>of</strong> the mountains <strong>of</strong> the Guiana<br />

Shield are generally localities <strong>of</strong> increased precipitation<br />

where these moisture-laden winds meet the slopes<br />

(Clarke et al. 2001). Seasonal oscillations <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) also bring<br />

variations in rainfall as the locations <strong>of</strong> low pressure<br />

zones near the equator change (Snow 1976). Varying<br />

primarily by latitude, one or two rainy seasons result<br />

from shifts in the ITCZ. The heaviest rains usually<br />

occur between May and August, whereas the rainy<br />

season running from December to January is shorter<br />

and less intense, with rains that do not penetrate as far<br />

inland. Even during most dry seasons, frequent storms<br />

provide adequate moisture to allow evergreen tropical<br />

moist forests to persist in most low elevation parts <strong>of</strong><br />

the region.<br />

<strong>Biological</strong> Diversity<br />

The variety <strong>of</strong> landscapes <strong>of</strong> the Guiana Shield<br />

includes sandstone tepuis, granite inselbergs, white<br />

sands, seasonally flooded tropical savannas, lowlands<br />

with numerous rivers, isolated mountain ranges, and<br />

coastal swamps, each supporting a characteristic<br />

vegetation (Huber 1995b, Huber et al. 1995). This<br />

variety accounts for a great deal <strong>of</strong> the high diversity<br />

and endemicity <strong>of</strong> the Shield’s biota. The highlands <strong>of</strong><br />

the Shield have a flora and fauna with numerous<br />

endemic species. Some tepui endemic species occur as<br />

low as 300 m in elevation, with increasing numbers by<br />

1500 to 1800 m, and fully developed communities<br />

occurring by 2000 m. Few if any plant or animal<br />

specimens have been collected from most medium to<br />

high elevation areas <strong>of</strong> the Guiana Shield. Many parts<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Shield are poorly explored, including parts <strong>of</strong><br />

Brazil north <strong>of</strong> the Amazon River, much <strong>of</strong> eastern<br />

Colombia, and the southern parts <strong>of</strong> Venezuela,<br />

Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana.<br />

Conservation<br />

With the exceptions <strong>of</strong> the populated localities such<br />

as Puerto Ayacucho, Ciudad Guayana, Ciudad Bolívar,<br />

Boa Vista, Georgetown, Paramaribo, Cayenne, the<br />

agricultural coastal areas, and open areas like the<br />

Rupununi Savanna, the environment <strong>of</strong> the Guiana<br />

Shield has benefited from limited access and low<br />

population densities, although this same isolation has<br />

hindered biodiversity research. Estimates vary, but<br />

much <strong>of</strong> the vegetation is still relatively undisturbed by<br />

human activities. Recently, however, the pace <strong>of</strong><br />

disturbance has greatly increased. Current threats to<br />

the environment include large-scale logging by Asian<br />

and local companies, large- and small-scale gold and<br />

diamond mining, oil prospecting, bauxite mining,<br />

hydroelectric dams, wildlife trade, and populationrelated<br />

pressures such as burning, grazing, agriculture,<br />

and the expansion <strong>of</strong> towns and villages. Taken<br />

together, these impacts have begun to take their toll,<br />

with vast areas vulnerable to increasing disturbance a<br />

fact easily observed by using Google Earth and<br />

‘‘flying’’ over the area.<br />

The status <strong>of</strong> conservation efforts varies by country.<br />

Throughout the Guiana Shield, many areas that are<br />

designated as protected or otherwise restricted are<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten only ‘‘paper’’ parks because <strong>of</strong> a lack <strong>of</strong><br />

infrastructure, funds, and will to actually protect the<br />

areas. Over the last four decades, Venezuela has<br />

established seven national parks, 29 natural monuments,<br />

and two biosphere reserves covering about<br />

142,280 km 2 , more than 30% <strong>of</strong> its share <strong>of</strong> the

4 BULLETIN OF THE BIOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF WASHINGTON<br />

Guiana Shield (Funk & Berry 2005). In Guyana, the<br />

progress <strong>of</strong> conservation efforts has been slower, with<br />

the only substantial protected area being Kaieteur<br />

National Park, its 627 km 2 comprising about 3% <strong>of</strong><br />

the country’s area (Kell<strong>of</strong>f 2003, Kell<strong>of</strong>f & Funk<br />

2004), with additional reserves under consideration.<br />

Guyana’s 3710 km 2 Iwokrama forest (Clarke et al.<br />

2001) has parts listed as reserves, but overall it is<br />

dedicated to sustainable use; unfortunately, logging<br />

has begun, and the section <strong>of</strong> the road from Boa Vista,<br />

Brazil, to Georgetown, Guyana, that runs through<br />

Iwokrama is about to be paved. Suriname’s protected<br />

areas system includes one national park and a network<br />

<strong>of</strong> 11 reserves, totaling almost 20,000 km 2 , over 12%<br />

<strong>of</strong> its total area. This includes the recently created<br />

16,000 km 2 Central Suriname Nature Reserve, a<br />

UNESCO World Heritage Site that joined and<br />

expanded three existing reserves (see http://www.<br />

stinasu.com). French Guiana has no <strong>of</strong>ficially designated<br />

protected areas, but 18 proposed sites total 6710<br />

km 2 , about 7.5% <strong>of</strong> its area (Lindeman & Mori 1989).<br />

The natural areas <strong>of</strong> Venezuela and Guyana are<br />

currently under the most anthropogenic pressure,<br />

while those <strong>of</strong> French Guiana are probably less<br />

threatened.<br />

The Shield encompasses part or all <strong>of</strong> six countries<br />

with six different governments, five <strong>of</strong>ficial languages<br />

and many more indigenous languages. Cooperation is<br />

sometimes hampered by border disputes, illegal crossborder<br />

activities involving gold and wildlife, and a lack<br />

<strong>of</strong> interest by governments that are located far away.<br />

The implementation <strong>of</strong> conservation practices is<br />

further complicated by many issues concerning the<br />

indigenous peoples <strong>of</strong> the region. All <strong>of</strong> these<br />

challenges will have to be overcome on the way to<br />

designing and maintaining a viable reserve system for<br />

the Guiana Shield. However, it is critical that we gain<br />

an understanding <strong>of</strong> the flora and fauna <strong>of</strong> the Shield<br />

area so that decisions can be made on critical areas that<br />

have high priority for conservation and so data can be<br />

collected from areas that might ultimately be destroyed.<br />

Because it is an ancient, fairly isolated<br />

geological area, it is rich in endemic plant and animal<br />

taxa, with many more likely to be discovered with<br />

additional exploration. In addition, because this area<br />

has been long neglected by biologists, it is <strong>of</strong>ten an area<br />

<strong>of</strong> ‘‘inadequate information’’ for many biodiversity<br />

analyses.<br />

This volume contains the fishes from the Guiana<br />

Shield, when paired with the previously published<br />

Checklist <strong>of</strong> the Terrestrial Vertebrates <strong>of</strong> the Guiana<br />

Shield (Hollowell & Reynolds 2005), we can examine<br />

the size and scope <strong>of</strong> Vertebrates, an important<br />

monophyletic group, known to inhabit the Guiana<br />

Shield. Table 2 lists the vertebrate groups and their<br />

sizes. The two checklists include a total <strong>of</strong> 53 orders,<br />

189 families, 1190 genera, and 301 species. A large<br />

Table 2.—Number <strong>of</strong> vertebrate taxa at different ranks.<br />

Orders Families Genera Species<br />

Amphibians 2 13 59 269<br />

Reptiles 3 22 119 295<br />

Mammals 11 35 143 282<br />

Birds 22 70 493 1004<br />

Fishes 15 49 376 1168<br />

Total 53 189 1190 3018<br />

percentage <strong>of</strong> the species (38%) are contributed by the<br />

fishes listed in this volume.<br />

Figure 2 compares the vertebrate diversity across the<br />

major political areas <strong>of</strong> the Guiana Shield and shows<br />

the species turnover between different areas. The<br />

mammals and reptiles have the most similar fauna<br />

across the Shield with a 58% and 53% overlap,<br />

respectively, between French Guiana (the extreme east)<br />

and Venezuela-Amazonas (the extreme west). Fish and<br />

birds have the least (24% and 10%, respectively). With<br />

fishes this can probably be explained by the fact that<br />

the headwaters <strong>of</strong> the rivers in the east are widely<br />

separated from those <strong>of</strong> the west. The rivers <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Shield in the west (Venezuela) have their source in the<br />

Venezuelan Guayana and the Andes, in the central<br />

portion (Guyana) the Essequibo drains mainly from<br />

the Acari Mountains which lie on the border with<br />

Brazil as does the Corantijn River (border between<br />

Guyana and Suriname). To the east, rivers such as the<br />

Maroni and Oyapock drain from the Tumuk-Humak<br />

Mountains. The bird diversity percentage <strong>of</strong> ‘turn over’<br />

was surprisingly small until one realizes that there are<br />

very different flyways that go across the eastern and<br />

western parts <strong>of</strong> the Shield. When the three major<br />

avenues <strong>of</strong> vertebrate mobility are examined (land, air,<br />

water), it seems that the land provides the most stable<br />

species make up and the air and water provide the<br />

least. Could this have anything to do with the resulting<br />

high species diversity <strong>of</strong> the birds and fishes?<br />

In the wider scope <strong>of</strong> biological understanding, the<br />

goal <strong>of</strong> checklists <strong>of</strong> this type is to understand diversity<br />

in terms <strong>of</strong> the spatial, evolutionary, and ecological<br />

settings <strong>of</strong> physical environments, rather than simply<br />

by political boundaries. The assembly <strong>of</strong> these lists is a<br />

step toward considering the fauna in terms <strong>of</strong> the<br />

geological entity <strong>of</strong> the Guiana Shield. Future studies<br />

will include the analyses <strong>of</strong> animal community composition<br />

on finer landscape scales, using developing<br />

abilities to produce customized checklists for research<br />

and conservation with Geographic Information System<br />

(GIS) technologies drawing upon comprehensive databases<br />

that include georeferenced museum specimen<br />

records.<br />

<strong>Biological</strong> Diversity <strong>of</strong> the Guiana Shield (BDG)<br />

The ‘‘<strong>Biological</strong> Diversity <strong>of</strong> the Guiana Shield<br />

Program’’ (BDG) is a field-oriented program <strong>of</strong> the

NUMBER 17 5<br />

Figure 2. A comparison <strong>of</strong> the species lists <strong>of</strong> the political areas <strong>of</strong> the Guiana Shield Region.<br />

National Museum <strong>of</strong> Natural History that began in<br />

1983 (federally funded since 1987). The goal <strong>of</strong> the<br />

BDG is to ‘‘study, document and preserve the<br />

biological diversity <strong>of</strong> the Guiana Shield.’’ Most <strong>of</strong><br />

the program’s field work has taken place in Guyana,<br />

but data analyses cover the majority <strong>of</strong> the Shield. In<br />

Guyana, the BDG operates under the auspices <strong>of</strong> the<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Guyana (UG). The BDG program is<br />

designed to provide specimens and data to address<br />

questions about many groups <strong>of</strong> organisms from<br />

locations across the Shield. Information from BDG<br />

collections and from other herbarium collections is<br />

used to produce checklists, vegetation maps, floristic<br />

and faunistic studies, revisions, and monographs. The<br />

data generated from these studies are used to ask<br />

questions about the make up <strong>of</strong> Guiana Shield<br />

biological diversity, such as species turnover rates,<br />

surrogate taxa, and areas <strong>of</strong> high diversity. Finally, the<br />

BDG is exploring practical applications <strong>of</strong> the data<br />

that have been collected through regular collaborations<br />

with conservation and government agencies.<br />

In addition to collecting and research, the BDG<br />

Program trains students and scientists in both the<br />

U.S.A. and Guyana, assists in their research, and has<br />

established and helped to maintain collections. Over<br />

the years several events have been hosted in Guyana,<br />

including two Amerindian training courses, two bird<br />

preparation courses, two plant identification courses, a<br />

variety <strong>of</strong> lectures at the University and public venues,<br />

and a public scientific symposium on the biological<br />

diversity <strong>of</strong> Guyana. We also <strong>of</strong>fer training opportunities;<br />

nearly every year since 1987 the Program has<br />

hosted at least one Guyanese student or UG staff<br />

member at the Smithsonian. Many have participated in<br />

the Natural History Museum’s Research Training<br />

Program or the SI/MAB training courses. BDG<br />

worked with the University <strong>of</strong> Guyana to raise funds<br />

from the Royal Bank <strong>of</strong> Canada to construct a new<br />

building, the ‘‘Centre for the Study <strong>of</strong> <strong>Biological</strong><br />

Diversity,’’ located on the campus <strong>of</strong> UG. More<br />

recently, we worked with UG to raise funds from<br />

USAID to build an extension on the original building.

6 BULLETIN OF THE BIOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF WASHINGTON<br />

The Centre houses collections and research space,<br />

provides a library, and houses a Geographic Information<br />

System (GIS) facility. The goal <strong>of</strong> the Centre is to<br />

combine research, education and conservation in the<br />

study <strong>of</strong> biological diversity. The Centre is funded from<br />

outside grants, but the staff is part <strong>of</strong> the University.<br />

Currently, the plant database maintained by BDG has<br />

161,108 specimen records and all sheets have been<br />

barcoded. The BDG Program is working to make its<br />

data available to the scientific community. The<br />

collections are being mapped using ArcMap and then<br />

displayed on Google Earth as place marks. The<br />

project, Georeferencing Plants <strong>of</strong> the Guiana Shield is<br />

available on the <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Botany</strong> public website<br />

(http://botany.si.edu/bdg/georeferencing.cfm).<br />

Acknowledgments<br />

Special thanks go to the University <strong>of</strong> Guyana and<br />

the Guyana EPA who have consistently supported our<br />

efforts, including Mike Tamessar, Indarjit Ramdass,<br />

and Philip da Silva, as well as past and present staff<br />

members <strong>of</strong> the Centre for the Study <strong>of</strong> <strong>Biological</strong><br />

Diversity, in particular Calvin Bernard. This is number<br />

153 in the Smithsonian’s <strong>Biological</strong> Diversity <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Guiana Shield Program publication series.<br />

References<br />

Arbeláez, M. V., & R. Callejas. 1999. Flórula de la Meseta de<br />

Arensica de la comunidad de Monochoa (Región de<br />

Araracuara, Medio Caquetá). Tropenbos, Bogotá, Colombia.<br />

Berry, P. E., B. K. Holst, & K. Yatskievych (eds.). 1995. Flora <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Venezuelan Guayana. Vol. 1: Introduction. J. A. Steyermark,<br />

P. E. Berry, & B. K. Holst, general eds. Missouri Botanical<br />

Garden, St. Louis, 306 pp.<br />

Clarke, H. D., V. Funk, & T. Hollowell. 2001. Using checklists and<br />

collections data to investigate plant diversity. I: a comparative<br />

checklist <strong>of</strong> the plant diversity <strong>of</strong> the Iwokrama Forest,<br />

Guyana.—Sida Botanical Miscellany 21:1–86.<br />

Doyle, A. C. 1912. The Lost World. Puffin Books, London.<br />

Ferrier, S., G. V. N. Powell, K. S. Richardson, G. Manion, J. M.<br />

Overton, T. F. Allnutt, S. E. Cameron, K. Mantle, N. D.<br />

Burgess, D. P. Faith, J. F. Lamoreux, G. Kier, R. J. Hijmans,<br />

V. A. Funk, G. A. Cassis, B. L. Fisher, P. Flemons, D. Lees, J.<br />

C. Lovett, & R. S. A. R. Van Rompaey. 2004. Mapping more<br />

<strong>of</strong> terrestrial biodiversity for Global Conservation assessment.—BioScience<br />

54(12):1101–1109.<br />

Funk, V. A., & P. E. Berry. 2005. The Guiana Shield. Pp. 76–79 in G.<br />

A. Krupnick & W. J. Kress, eds., Plant conservation: a natural<br />

history approach. University <strong>of</strong> Chicago Press, Chicago, 235<br />

pp.<br />

———, & K. S. Richardson. 2002. Systematic data in biodiversity<br />

studies: use it or lose it.—Systematic Biology 51:303–316.<br />

———, ———, & S. Ferrier. 2005. Survey-gap analysis in<br />

expeditionary research: where do we go from here?—<br />

<strong>Biological</strong> Journal <strong>of</strong> the Linnean <strong>Society</strong> 85:549–567.<br />

———, A. K. Sakai, & K. Richardson. 2002. Biodiversity: the<br />

interface between systematics and conservation.—Systematic<br />

Biology 51:235–237.<br />

———, T. Hollowell, P. Berry, C. Kell<strong>of</strong>f, & S. N. Alexander. 2007.<br />

Checklist <strong>of</strong> the plants <strong>of</strong> the Guiana Shield (Venezuela:<br />

Amazonas, Bolívar, Delta Amaçuro; Guyana, Surinam,<br />

French Guiana).—Contributions from the United States<br />

National Herbarium 55:1–584.<br />

Gibbs, A. K., & C. N. Barron. 1993. The geology <strong>of</strong> the Guiana<br />

Shield. Oxford University Press, New York, 246 pp.<br />

Hollowell, T., & R. P. Reynolds (eds.). 2005. Checklist <strong>of</strong> the<br />

terrestrial vertebrates <strong>of</strong> the Guiana Shield.—Bulletin <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>Biological</strong> <strong>Society</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Washington</strong> 13:i–ix + 1–98.<br />

Huber, O. 1995a. Geography and physical features. Pp. 1–61 in P. E.<br />

Berry, B. K. Holst, & K. Yatskievych, eds., Flora <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Venezuelan Guayana. Vol. 1: Introduction. J. A. Steyermark,<br />

P. E. Berry, & B. K. Holst, general eds. Missouri Botanical<br />

Garden, St. Louis.<br />

——— 1995b. Vegetation. Pp. 97–160 in P. E. Berry, B. K. Holst, &<br />

K. Yatskievych, eds., Flora <strong>of</strong> the Venezuelan Guayana. Vol.<br />

1: Introduction. J. A. Steyermark, P. E. Berry, & B. K. Holst,<br />

general eds. Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis.<br />

———, G. Gharbarran, & V. A. Funk. 1995. Preliminary vegetation<br />

map <strong>of</strong> Guyana. <strong>Biological</strong> Diversity <strong>of</strong> the Guianas Program,<br />

Smithsonian Institution,<strong>Washington</strong>, D.C.<br />

Kell<strong>of</strong>f, C. L. 2003. The use <strong>of</strong> biodiversity data in developing<br />

Kaieteur National Park, Guyana, for ecotourism and<br />

conservation.—Contributions to the Study <strong>of</strong> <strong>Biological</strong><br />

Diversity, University <strong>of</strong> Guyana, Georgetown 1:1–44.<br />

———, & V. A. Funk. 2004. Phytogeography <strong>of</strong> the Kaieteur Falls,<br />

Potaro Plateau, Guyana: floral distributions and affinities.—<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> Biogeography 31:501–513.<br />

Leechman, A. 1913. The British Guiana handbook. ‘‘The Argosy’’<br />

Co., Ltd., Georgetown, British Guiana, and Dulau & Co.,<br />

London, 283 pp.<br />

Lindeman, J. C., & S. A. Mori. 1989. The Guianas. Pp. 375–391 in D.<br />

G. Campbell & H. D. Hammond, eds., Floristic inventory <strong>of</strong><br />

tropical countries. New York Botanical Garden, New York.<br />

Mendoza, V. 1977. Evolución tectónica del Escudo de Guayana.—<br />

Boletín de Geología. Publicación Especial 7(3):2237–2270.<br />

Reis, R. E., S. O. Kullander, & C. J. Ferraris, Jr. (eds.). 2003. Check<br />

list <strong>of</strong> the freshwater fishes <strong>of</strong> South and Central America.<br />

Edipucrs, Porto Alegre, Brazil, 729 pp.<br />

Schubert, C., & O. Huber. 1990. The Gran Sabana: panorama <strong>of</strong> a<br />

region. Lagoven Booklets, Caracas, 107 pp.<br />

Snow, J. W. 1976. Climates <strong>of</strong> northern South America. Pp. 295–403<br />

in W. Schwerdtfeger, ed., Climates <strong>of</strong> Central and South<br />

America. Elsevier Scientific Publishing Company, Amsterdam.

History<br />

A vast complex <strong>of</strong> wetlands, lakes, streams, and<br />

rivers drains the broad savannas, dense rainforests,<br />

extensive uplands, and tepuis <strong>of</strong> the Guiana Shield.<br />

Early European explorers and colonists were impressed<br />

not only by the many unusual fish species dwelling in<br />

these water systems but also by the diversity <strong>of</strong> the<br />

ichthy<strong>of</strong>auna. Accounts <strong>of</strong> fishes from those drainage<br />

systems commenced with descriptions by pre-Linnaean<br />

naturalists (e.g., Gronovius 1754, 1756) based on<br />

specimens returned to Europe, with Linnaeus (1758)<br />

formally describing a number <strong>of</strong> these species.<br />

Much <strong>of</strong> the early descriptive activity involving<br />

fishes <strong>of</strong> the Guiana Shield centered on the ichthy<strong>of</strong>auna<br />

<strong>of</strong> British Guiana (5 Guyana). Commentaries<br />

on fishes from that colony by Bancr<strong>of</strong>t (1769) and<br />

Hilhouse (1825) preceded the formal description <strong>of</strong><br />

catfish species from the Demerara by Hancock (1828).<br />

Cuvier and Valenciennes summarized the available<br />

information on the ichthy<strong>of</strong>auna <strong>of</strong> all <strong>of</strong> the Guianas<br />

in their series entitled Histoire Naturelle des Poissons<br />

that documented the fish species known worldwide to<br />

science to that time; with the catfishes being the first <strong>of</strong><br />

the groups inhabiting the shield discussed by those<br />

authors (Cuvier & Valenciennes 1840a, b). These and<br />

the other treatments <strong>of</strong> that era were, however, largely<br />

opportunistic accounts based on scattered samples<br />

returned to Europe rather than derivative <strong>of</strong> focused<br />

studies on the fish fauna <strong>of</strong> any region on the shield.<br />

Consequently, the scale <strong>of</strong> the species-level diversity <strong>of</strong><br />

that ichthy<strong>of</strong>auna remained unknown and underappreciated.<br />

Indications <strong>of</strong> the scale <strong>of</strong> the richness <strong>of</strong> the fish<br />

fauna inhabiting the rivers <strong>of</strong> the Guiana Shield<br />

commenced with the expeditions <strong>of</strong> the Schomburgk<br />

brothers, Richard and Robert. In a remarkable<br />

endeavor for that era, Robert collected fishes from<br />

1835 to 1839 both in the more accessible shorter<br />

northerly flowing rivers <strong>of</strong> the Guianas and through<br />

portions <strong>of</strong> the Río Orinoco and Río Negro and the<br />

Rio Branco. Drawings <strong>of</strong> fishes prepared during<br />

Schomburgk’s travels across the shield served as the<br />

basis for 83 species accounts in Jardine’s ‘‘Naturalist’s<br />

Library’’ (1841, 1843), including the formal descriptions<br />

<strong>of</strong> a series <strong>of</strong> species. Unfortunately, the specimens<br />

that were the basis for the drawings were not<br />

preserved, and some illustrations combined details <strong>of</strong><br />

more than one species. Subsequent expeditions by the<br />

Schomburgks traversed portions <strong>of</strong> what are now<br />

Guyana, Venezuela, Suriname, and Brazil and yielded,<br />

what was for that time, large numbers <strong>of</strong> fish specimens.<br />

In a series <strong>of</strong> publications Müller & Troschel (1845,<br />

FISHES OF THE GUIANA SHIELD<br />

RICHARD P. VARI and CARL J. FERRARIS, JR.<br />

1848, 1849) recognized 141 species in the Schomburgk<br />

collections and provided the first detailed illustrations<br />

<strong>of</strong> fishes from South American freshwaters.<br />

Diverse factors resulted in a lag in the state <strong>of</strong><br />

knowledge <strong>of</strong> the fishes inhabiting many portions <strong>of</strong><br />

the shield, with the comparative difficulty in accessibility<br />

to inland regions clearly a paramount issue for<br />

many areas. Supplementing that impediment were a<br />

series <strong>of</strong> misadventures that bedeviled collectors who<br />

sampled the fish fauna <strong>of</strong> the western portions <strong>of</strong> the<br />

shield. Alexandre Rodriques Ferreira headed an<br />

expedition that explored a significant portion <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Rio Negro basin, commencing with a major collecting<br />

effort through the Rio Branco system in 1786 (Ferreira<br />

et al. 2007:12). Confounding Ferreira’s attempts to<br />

publish his results were a string <strong>of</strong> unfortunate events<br />

that culminated with the 1807 invasion <strong>of</strong> Portugal by<br />

Napoleonic forces and the seizure and shipment <strong>of</strong><br />

Ferreira’s collections to Paris. Ferreira’s report on<br />

animals from the Rio Branco region remained unpublished<br />

until long after his death, and even then, only<br />

parts appeared in print (see references in Ferreira<br />

1983). In two expeditions between 1850 and 1852,<br />

Alfred Russel Wallace (<strong>of</strong> Natural Selection fame)<br />

collected over 200 species <strong>of</strong> fishes throughout the Rio<br />

Negro basin including rivers draining the shield.<br />

Wallace’s collections were lost with the sinking <strong>of</strong> the<br />

ship returning him to England. Nonetheless, his field<br />

sketches (Wallace 2002) document that the lost<br />

collection included a number <strong>of</strong> species <strong>of</strong> fishes then<br />

unknown to science (Regan 1905a, Toledo-Piza et al.<br />

1999, Vari & Ferraris 2006).<br />

An accelerating pace <strong>of</strong> ichthyological collecting<br />

across many portions <strong>of</strong> the Guiana Shield during the<br />

latter part <strong>of</strong> the nineteenth century resulted in the<br />

discovery and description <strong>of</strong> numerous species. These<br />

collections also documented the presence on the Shield<br />

<strong>of</strong> many species originally described from elsewhere in<br />

cis-Andean South America. Notwithstanding those<br />

advances, the information was dispersed through<br />

revisionary (e.g., Regan 1905b, c) and monographic<br />

studies (e.g., Eigenmann & Eigenmann 1890), general<br />

ichthy<strong>of</strong>aunal summaries <strong>of</strong> regions on the shield (e.g.,<br />

Pellegrin 1908), and species descriptions in multiple<br />

languages.<br />

Exceptions to this pattern <strong>of</strong> scattered publication<br />

were limited to a handful <strong>of</strong> papers focused on subsets<br />

<strong>of</strong> the ichthy<strong>of</strong>auna from comparatively small regions.<br />

Among the more notable <strong>of</strong> these were the analysis <strong>of</strong><br />

the catfishes <strong>of</strong> Suriname (Bleeker 1862), discussions <strong>of</strong><br />

the fishes present in portions <strong>of</strong> French Guiana<br />

(Vaillant 1899, 1900), and a semi-popular overview <strong>of</strong>

10 BULLETIN OF THE BIOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF WASHINGTON<br />

the fishes <strong>of</strong> French Guiana (Pellegrin 1908). Compendia<br />

<strong>of</strong> the freshwater fish species known from<br />

individual colonies, countries, or regions were not<br />

developed, let alone summaries <strong>of</strong> the fishes inhabiting<br />

in the numerous streams, rivers, and lakes across the<br />

shield. The dispersed literature prevented an appreciation<br />

<strong>of</strong> the scale <strong>of</strong> the diversity <strong>of</strong> the shield<br />

ichthy<strong>of</strong>auna.<br />

The first overview <strong>of</strong> the freshwater fishes <strong>of</strong><br />

northeastern South America, including the Guiana<br />

Shield, was Eigenmann’s (1912) treatise on the<br />

freshwater fishes <strong>of</strong> British Guiana. Although Eigenmann<br />

sampled the fish fauna <strong>of</strong> only a comparatively<br />

small section <strong>of</strong> British Guiana, his collections were<br />

extensive for that era. In a series <strong>of</strong> papers, he and his<br />

students described 128 new species from those collections<br />

(Eigenmann 1912:133). Eigenmann’s monograph<br />

included data from his own collections, information<br />

from the literature, and records <strong>of</strong> fishes that<br />

originated on the Shield in various museums. Summary<br />

tables (Eigenmann 1912:64) detailed the fish species<br />

known from ten subunits that fall, at least in part,<br />

within the boundaries <strong>of</strong> the Guiana Shield (Río<br />

Orinoco basin, ‘‘West Coast’’ <strong>of</strong> British Guiana<br />

[5 Barima River basin], Rio Branco basin, Rupununi<br />

River, Lower Essequibo River, Lower Potaro River,<br />

Demerara River, Dutch Guiana [5 Suriname], and<br />

French Guiana [5 Guyane Française]).<br />

Eigenmann (1912) reported 493 species from those<br />

ten geographic units; a total that was in excess <strong>of</strong> the<br />

species reported to that time from the rivers <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Shield. These additional species were a function <strong>of</strong> two<br />

factors. His total included all <strong>of</strong> the fish species then<br />

known to inhabit the Río Orinoco; however, that vast<br />

river system extends far beyond the Shield boundaries<br />

with approximately only 40% <strong>of</strong> that watershed<br />

overlying the Shield. Many <strong>of</strong> the fish species known<br />

at the end <strong>of</strong> the first decade <strong>of</strong> the twentieth century<br />

from the Río Orinoco basin originated in the llanos<br />

(savannas) <strong>of</strong> the north central and western portions <strong>of</strong><br />

the basin. Aquatic habitats and the fish faunas in these<br />

floodplain savanna settings differ dramatically from<br />

the ecosystems and fish communities <strong>of</strong> the more<br />

rapidly flowing rivers that drain the forested northern<br />

slope <strong>of</strong> the Guiana Shield. Further inflating Eigenmann’s<br />

species total was his inclusion <strong>of</strong> some<br />

primarily marine forms. Such species penetrate the<br />

lower reaches <strong>of</strong> the rivers draining the Guianas during<br />

periods <strong>of</strong> low river flow and consequent increased<br />

estuarine salinity. Few, if any, <strong>of</strong> these species are likely<br />

to range upriver onto the Shield even during the height<br />

<strong>of</strong> the dry season.<br />

The decades since Eigenmann’s monograph have<br />

seen numerous ichthyological collecting expeditions in<br />

many systems on the Shield. Two wide-ranging and<br />

productive collecting endeavors through that region<br />

during the first half <strong>of</strong> the twentieth century remain<br />

relatively poorly known. John Haseman, who collected<br />

throughout the Rio Branco basin and the southernmost<br />

portion <strong>of</strong> the Rupununi River system in 1912<br />

and 1913, made the first <strong>of</strong> these. Haseman deposited<br />

these extensive collections in the Naturhistorisches<br />

Museum in Vienna where he studied them for a year in<br />

collaboration with Franz Steindachner. Nonetheless,<br />

only one major publication based on those collections<br />

was published (Steindachner 1915), most likely because<br />

<strong>of</strong> the onset <strong>of</strong> World War I, disruptions during and<br />

immediately after the conflict, and the death <strong>of</strong><br />

Steindachner soon after the cessation <strong>of</strong> hostilities.<br />

Various revisionary studies in recent decades incorporated<br />

subsets <strong>of</strong> Haseman’s collection; nonetheless,<br />

much <strong>of</strong> the material is yet-to-be analyzed critically.<br />

The second collector, Carl Ternetz, sampled fishes<br />

through the Rio Negro, Río Casiquiare, and Río<br />

Orinoco basins during 1924 and 1925. Myers<br />

(1927:107) remarked that the collection was ‘‘a<br />

magnificent series <strong>of</strong> fishes, most <strong>of</strong> them hitherto<br />

unexplored systematically by an ichthyologist.’’ Notwithstanding<br />

the description <strong>of</strong> some new species<br />

collected by Ternetz in rivers <strong>of</strong> the shield by Myers<br />

(1927) and other authors and the use <strong>of</strong> portions <strong>of</strong><br />

that collection in some studies (e.g., Myers & Weitzman<br />

1960), most <strong>of</strong> the material remains unstudied,<br />

even after its transfer from Indiana University to the<br />

California Academy <strong>of</strong> Sciences.<br />

The 1960s brought a resurgence <strong>of</strong> major ichthyological<br />

collecting efforts in many <strong>of</strong> the river systems<br />

on the shield (e.g., the Brokopondo Project; Boeseman<br />

1968:4), with the pace <strong>of</strong> these endeavors accelerating<br />

during recent decades. A compendium <strong>of</strong> these<br />

collecting efforts lies beyond the purpose and scope<br />

<strong>of</strong> this paper; however, as summarized in the next<br />

section many <strong>of</strong> these expeditions were integral to<br />

checklists, regional revisionary studies, and summaries<br />

<strong>of</strong> the ichthy<strong>of</strong>auna in river basins or regions <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Shield.<br />

State <strong>of</strong> Knowledge <strong>of</strong> the Shield Fish Fauna<br />

The nearly ten decades since the preparation <strong>of</strong><br />

Eigenmann’s 1912 magnum opus saw numerous<br />

publications on fishes <strong>of</strong> the Guiana Shield. Many<br />

were revisionary studies <strong>of</strong> genera or families whose<br />

ranges extend far beyond the limits <strong>of</strong> the Shield, <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

across major portions <strong>of</strong> cis-Andean South America<br />

and in some instances into trans-Andean regions or<br />

occasionally Central America. Other publications were<br />

restricted to the members <strong>of</strong> a genus, subfamily, or<br />

family from a country within the Shield region (e.g.,<br />

Suriname: Boeseman 1968, Nijssen 1970, Kullander &<br />

Nijssen 1989) or across a major portion <strong>of</strong> that area<br />

(e.g., Boeseman 1982). Relatively few <strong>of</strong> these papers<br />

involved broad surveys <strong>of</strong> an entire ichthy<strong>of</strong>auna in a<br />

river system or country on the Shield with those that

NUMBER 17 11<br />

did so summarized below arranged by the geographic<br />

subdivisions in the checklist. Many include associated<br />

ecological and life history information for fish communities<br />

and individual species.<br />

Brazil, Pará (PA). The single publication <strong>of</strong> note<br />

from this region is Ferreira (1993) that summarized the<br />

results <strong>of</strong> intensive collecting efforts at sites within the<br />

Rio Trombetas, one <strong>of</strong> the major northern tributaries<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Amazon River east <strong>of</strong> the Rio Negro.<br />

Brazil, Roraima (RO). Ferreira et al. (1988) summarized<br />

the ichthy<strong>of</strong>auna at several closely situated<br />

localities in the Rio Mucajai, a tributary <strong>of</strong> the Rio<br />

Branco. More recently, Ferreira et al. (2007) provided<br />

detailed information on the ichthy<strong>of</strong>auna across the<br />

expanse <strong>of</strong> the Rio Branco basin, supplemented by<br />

numerous color photographs, discussions <strong>of</strong> habitats,<br />

and comments on the anthropogenic impact on the<br />

aquatic systems within the basin.<br />

French Guiana (FG). French Guiana has the most<br />

intensely studied ichthy<strong>of</strong>auna <strong>of</strong> any portion <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Guyana Shield. The first attempt to summarize<br />

information on the fishes <strong>of</strong> the entire department<br />

was that <strong>of</strong> Puyo (1949). Géry (1972) followed up with<br />

studies <strong>of</strong> the characiforms (his characoids) from the<br />

Guianas with a particular focus on French Guiana.<br />

Planquette et al. (1996), Keith et al. (2000), and Le Bail<br />

et al. (2000), in a groundbreaking series <strong>of</strong> publications,<br />

brought together information on the spectrum <strong>of</strong><br />

the freshwater fish fauna in that department. Each<br />

species account includes a description, illustration, and<br />

comments on its biology. Distributions within and<br />

beyond French Guiana are discussed, and the sites <strong>of</strong><br />

occurrences <strong>of</strong> the species in the department are<br />

plotted.<br />

Guyana (GU). Notwithstanding the title <strong>of</strong> the<br />

publication, Eigenmann’s (1912) monographic study<br />

was based primarily on collections from the northern<br />

portions <strong>of</strong> Guyana, in particular the Potaro River and<br />

lower courses <strong>of</strong> the Essequibo and Demerara rivers,<br />

albeit with that data supplemented with information<br />

from the literature. Hardman et al. (2002) reported on<br />

the fish fauna captured at Eigenmann’s collecting<br />

localities nine decades after his expedition and provided<br />

a checklist <strong>of</strong> the 272 species collected in that survey.<br />

Lowe (McConnell) (1964) included lists <strong>of</strong> fishes from<br />

the southern most reaches <strong>of</strong> the Essequibo River<br />

system along with observations on their ecology and on<br />

the movements <strong>of</strong> various species during the yearly<br />

flood and drought cycles. Watkins et al. (2004)<br />

provided a summary <strong>of</strong> the fishes <strong>of</strong> the Iwokrama<br />

Forest Reserve.<br />

Suriname (SU). The ichthy<strong>of</strong>auna <strong>of</strong> Suriname<br />

remains relatively poorly documented, with the listing<br />

<strong>of</strong> the freshwater fishes in the country by Eigenmann<br />

(1912:64–73) largely derived from literature information.<br />

Boeseman (1952, 1953, 1954) supplemented<br />

Eigenmann’s listing. Ouboter & Mol (1993) presented<br />

the most comprehensive published list <strong>of</strong> the freshwater<br />

fishes <strong>of</strong> Suriname. Kullander & Nijssen (1989)<br />

published a detailed analysis <strong>of</strong> the cichlids <strong>of</strong><br />

Suriname.<br />

Venezuela, Amazonas (VA). The state <strong>of</strong> Amazonas,<br />

Venezuela, includes portions <strong>of</strong> the south-flowing Río<br />

Negro <strong>of</strong> the Amazon basin, the north-draining Río<br />

Orinoco and the entirety <strong>of</strong> the intervening Río<br />

Casiquiare. Mago-Leccia (1971) produced the first<br />

summary <strong>of</strong> the fishes <strong>of</strong> the Río Casiquiare. Lasso<br />

(1992), Royero et al. (1992), and Lasso et al. (2004a,<br />

2004b) provided information on the fish faunas <strong>of</strong><br />

various river systems within the state.<br />

Venezuela, Bolivar (BO). A series <strong>of</strong> studies treated<br />

the fish fauna <strong>of</strong> several right bank tributaries <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Río Orinoco that drain the northern slopes <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Guyana Shield. These included summaries <strong>of</strong> species in<br />

various basins, with those listings supplemented in<br />

some instances by information on fish biology and<br />

distribution. Significant publications on the ichthy<strong>of</strong>auna<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Río Caroni were published by Lasso<br />

(1991) and Lasso et al. (1991a, b) and for the Río<br />

Caura by Lasso et al. (2003a, b), Rodríquez-Olarte et<br />

al. (2003), and Vispo et al. (2003). The Río Cuyuni, a<br />

western tributary <strong>of</strong> the Essequibo River, drains the<br />

eastern portions <strong>of</strong> the Shield in the state <strong>of</strong> Bolivar.<br />

Machado-Allison et al. (2000) summarized the fish<br />

fauna <strong>of</strong> the Venezuelan portions <strong>of</strong> that river system.<br />

Lasso et al. (2004a) and Girardo et al. (2007) provide<br />

supplemental information on the ichthy<strong>of</strong>auna <strong>of</strong> that<br />

drainage basin.<br />

Ichthy<strong>of</strong>aunal Richness<br />

This checklist <strong>of</strong> fishes known from the water<br />

systems <strong>of</strong> the Guiana Shield includes 1168 species.<br />

Included in that total are representatives <strong>of</strong> 376 genera,<br />

49 families, and 15 orders. Five orders are dominant in<br />

terms <strong>of</strong> number <strong>of</strong> species living on the shield and<br />

account for 96.7% <strong>of</strong> the species (Characiformes, 478<br />

species and 41.0%; Siluriformes, 425 species and 36.4%;<br />

Perciformes, 126 species and 10.8%; Gymnotiformes,<br />

52 species and 4.5%; Cyprinodontiformes, 47 species<br />

and 4.0%). This sum <strong>of</strong> 1168 species attests to the<br />

dramatic improvement <strong>of</strong> our knowledge <strong>of</strong> the<br />

freshwater fish fauna on the Shield in slightly less than<br />

a century since Eigenmann (1912) documented fewer<br />

than 500 species from that region. The 1168 species are<br />

approximately 4.1% <strong>of</strong> the 28,400 fish species recently<br />

estimated to be present in all marine and freshwater<br />

systems worldwide (Nelson 2006), a percentage that<br />

amply testifies to the striking diversity <strong>of</strong> the ichthy<strong>of</strong>auna<br />

within that region. All the more noteworthy is<br />

the species-level richness <strong>of</strong> the ichthy<strong>of</strong>auna within the<br />

context <strong>of</strong> the overall Neotropical freshwater fish<br />

fauna. According to a recent summary, approximately<br />

5000 species <strong>of</strong> freshwater fishes occur across the

12 BULLETIN OF THE BIOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF WASHINGTON<br />

entirety <strong>of</strong> Central and South America (Reis et al.<br />

2003). Thus, the drainage systems <strong>of</strong> the Guiana Shield<br />

are home to approximately 23% <strong>of</strong> the freshwater fish<br />

species that occur across the vast expanse between<br />

southern South America and the southern border <strong>of</strong><br />

Mexico. Many factors contributed to the Shield region<br />

being a repository <strong>of</strong> freshwater ichthyological diversity,<br />

with a few particularly worthy <strong>of</strong> comment.<br />

Physiography<br />

The Guiana Shield is the ancient Precambrian<br />

Guianan formation resulting from the uplift <strong>of</strong> the<br />

underlying craton (Gibbs & Barron 1993) and demonstrates<br />

attributes that generally lead to high levels <strong>of</strong><br />

biodiversity: geological diversity, a topographically<br />

variable landscape, and transitions between ecosystems<br />

(Killeen et al. 2002). Overall the region has a primarily<br />

low to somewhat hilly physiography, albeit with some<br />

abrupt changes in topography in the regions proximate<br />

to the tepui formations that extend across much <strong>of</strong> the<br />

region in an approximately east to west alignment.<br />

Some river valleys have marked shifts in topography<br />

with resultant waterfalls, rapids, and riffles that<br />

increase the complexity <strong>of</strong> drainage system structure.<br />