Michael J. Thompson Stephen Eric Bronner Wadood Hamad - Logos

Michael J. Thompson Stephen Eric Bronner Wadood Hamad - Logos

Michael J. Thompson Stephen Eric Bronner Wadood Hamad - Logos

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

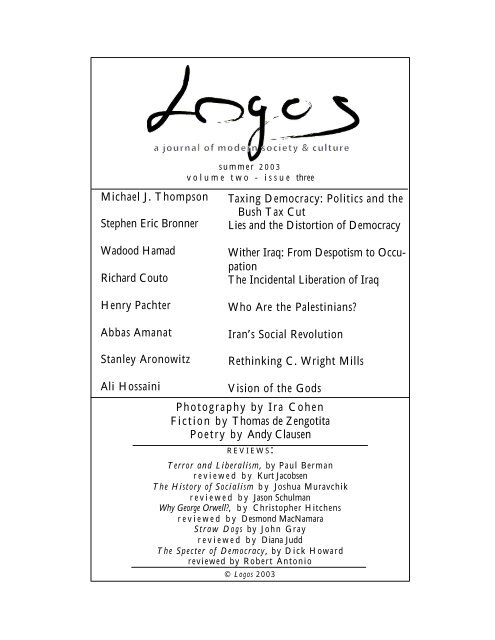

<strong>Michael</strong> J. <strong>Thompson</strong><br />

<strong>Stephen</strong> <strong>Eric</strong> <strong>Bronner</strong><br />

<strong>Wadood</strong> <strong>Hamad</strong><br />

Richard Couto<br />

Henry Pachter<br />

Abbas Amanat<br />

Stanley Aronowitz<br />

Ali Hossaini<br />

summer 2003<br />

volume two - issue three<br />

Taxing Democracy: Politics and the<br />

Bush Tax Cut<br />

Lies and the Distortion of Democracy<br />

Wither Iraq: From Despotism to Occupation<br />

The Incidental Liberation of Iraq<br />

Who Are the Palestinians?<br />

Iran’s Social Revolution<br />

Rethinking C. Wright Mills<br />

Vision of the Gods<br />

Photography by Ira Cohen<br />

Fiction by Thomas de Zengotita<br />

Poetry by Andy Clausen<br />

REVIEWS:<br />

Terror and Liberalism, by Paul Berman<br />

reviewed by Kurt Jacobsen<br />

The History of Socialism by Joshua Muravchik<br />

reviewed by Jason Schulman<br />

Why George Orwell?, by Christopher Hitchens<br />

reviewed by Desmond MacNamara<br />

Straw Dogs by John Gray<br />

reviewed by Diana Judd<br />

The Specter of Democracy, by Dick Howard<br />

reviewed by Robert Antonio<br />

© <strong>Logos</strong> 2003

F<br />

<strong>Michael</strong> J. <strong>Thompson</strong><br />

Taxing Democracy:<br />

Politics and the Bush Tax Cut<br />

by<br />

<strong>Michael</strong> J. <strong>Thompson</strong><br />

<strong>Logos</strong> 2.3 – Summer 2003<br />

The science of economics is a political science.<br />

—Max Weber<br />

ew domestic political issues have been debated with more passion than<br />

the tax cut that was proposed by the Bush administration and recently<br />

passed by Congress. The tax cuts have been characterized as everything from<br />

a giveaway to the rich to a stimulus package for an ailing economy. Political<br />

rhetoric frequently coalesces with “social science,” statistics and economic<br />

argumentation, but—interestingly enough—the political character of<br />

decision-making on tax policy has tended to disappear from the public<br />

debate. What I think is happening, however, is not simply a rethinking of tax<br />

codes or a move away from the redistributional character of the post-war<br />

American welfare state. Rather, there is a reformation of American democracy<br />

through the policy prescriptions of the Bush administration where the acute<br />

separation of economics from politics may very well lead to an erosion of the<br />

democratic character of the United States. What characterizes the political<br />

rhetoric of the Bush administration and neoconservatives?<br />

Without question, linking taxes and democracy has been a consistent theme<br />

in American politics. From the birth of the republic, through the massive<br />

inequities of the Gilded Age and the great redistributive policies of the New<br />

Deal, the War On Poverty and the Great Society, there has always existed a<br />

consistent link between the emergence of the state as a participant in the<br />

public sphere and the expansion of democracy, especially in economic terms.<br />

But recently, the view has emerged that the expansion of the state and the<br />

services it provides, its public goods—what we commonly call the welfare<br />

state—stands in sharp contradiction to the values of liberty, freedom and<br />

democracy. The more the state encroaches on me, the citizen, the less free I<br />

am; the less money I am able to keep from what I earn, the more the<br />

government is interfering with my liberty. This is the essential rhetoric of<br />

anti-tax conservatives like Grover Norquist, one of George W. Bush’s top<br />

political advisors:

<strong>Michael</strong> J. <strong>Thompson</strong><br />

Look, the center right coalition in American politics today is<br />

best understood as a coalition of groups and individuals [and]<br />

the issue that brings them to politics [is that] what they want<br />

from the government is to be left alone. Taxpayers, don’t raise<br />

my taxes. Property owners, don’t restrict or limit my property.<br />

Home-schoolers, let me educate my own kids. Gun owners,<br />

don’t restrict my Second Amendment rights. All communities<br />

of faith, Evangelical Christians, conservative Catholics,<br />

Mormons, Muslims, Orthodox Jews, people want to practice<br />

their own religion and be left alone to raise their own kids. 1<br />

Known as the “leave us alone” coalition, such is the ideological context that<br />

includes the politics of the most recent tax cuts; an ideology grounded in a<br />

much broader conception of society, politics and culture; one premised on a<br />

curious mix of libertarian individualism with a provincial, parochial<br />

communitarianism. But this is merely a surface phenomenon. It appeals only<br />

to the conservative sentiments of a public that has been ideologically dragged<br />

to the right over the past two and a half decades. But the material impact of<br />

the tax cuts are typically felt at the local levels. This is, in part, a result of tax<br />

cutting policies which begin at the federal level and have trickled down over<br />

the years into the policies of states.<br />

As federal tax cuts increased throughout the 1980s and 1990s there was an<br />

increased pressure states and cities to shoulder the cost of schools and other<br />

social services. The politics of the tax cut must therefore be seen first and<br />

foremost as a broad attempt to reorient the way in which American<br />

democracy was heading since the New Deal which itself was based on the<br />

realization that the effects of capitalism on society required the intervention<br />

of the state in order to counteract the effects of what <strong>Stephen</strong> <strong>Eric</strong> <strong>Bronner</strong><br />

has called the “whip of the market” from staggering economic inequality and<br />

poverty reduction and cyclical economic crises. Later, issues ranging from<br />

pollution to enhanced social services and programs were on the minds of the<br />

public and began to enter the political agenda of the Democratic Party. It was<br />

a conception of democracy that realized that unequal economic power<br />

rendered “equal” political rights practically meaningless and that only<br />

through the fair distribution of social wealth could political and social rights<br />

truly be extended and realized.<br />

<strong>Logos</strong> 2.3 – Summer 2003

<strong>Michael</strong> J. <strong>Thompson</strong><br />

One of the main functions of tax policy is the redistribution of income and it<br />

is around this issue that the rallying cry for those who seek the reformation of<br />

the tax code in America is organized. Whatever else taxes may actually do as<br />

an instrument of public policy, the core argument used for the tax cuts has<br />

consistently been to link economic productivity (the welfare of everyone) and<br />

personal income (the welfare of the individual or family). It is, in so many<br />

ways, a flawless political strategy—one that hits Americans where they feel<br />

they need it the most, even though the numbers do not work out in their<br />

benefit. Most taxpayers therefore see their responsibility as restricted to the<br />

sphere of the local. In this sense, an element of racism often enters the picture<br />

once largely white and better-off municipalities pay taxes that are<br />

redistributed to inner city neighborhoods located close by. What is seen by<br />

the average taxpayer is therefore not a set of goods and services, but a<br />

complex tax system that is impenetrable and, at the local level, even seen as<br />

simply unfair where ailing inner city schools require tax revenues collected at<br />

the state or county level from more affluent, largely white suburbs.<br />

Redistribution is one of the main targets of the Bush tax cut and its impact<br />

will be substantial. Recent data show that, even before the current tax cut was<br />

put into effect, the top 400 wealthiest taxpayers paid less taxes in 2000 than<br />

in both 1995 and in 1992. In the past nine years, the incomes of the “top<br />

400 tax payers increased 15 times the rate of the bottom 90 percent of<br />

Americans.” 2 And it is important to point out in this context that the top 1<br />

percent of income earners in America have a 26 percent share of the tax<br />

burden while their share of the Bush tax cuts is over 50 percent. 3<br />

However we may view the rhetoric of the tax cuts, what is becoming ever<br />

more apparent is a gradual destruction of the public sector and the expansion<br />

of the market to more domains of society. In this sense, the Bush tax cuts are<br />

not merely an expression of fiscal policy. They also fundamentally serve a<br />

larger project of redirecting the way that American democracy has functioned<br />

throughout the post-war era. This redirection involves a wholesale<br />

transformation in the way that government can act to soften the harsh<br />

impacts of the capitalist economy whether it is in the form of economic<br />

inequality or environmental degradation.<br />

<strong>Logos</strong> 2.3 – Summer 2003

<strong>Michael</strong> J. <strong>Thompson</strong><br />

Tax Reform and Political Opportunism: Bush in Context<br />

THE TREND TOWARD TAX REFORM in the 1980s was, it should be admitted,<br />

the result of many legitimate economic pressures. The problem was not in<br />

the changing economics of global capitalism but in the way the politics of the<br />

right in America—as well as other nations—used this economic pressure for<br />

its own ideological ends. This can be explained in the flowing way. During<br />

the post-war years, there was a general consensus among policy makers that<br />

taxes should be progressive and used as tools for economic management.<br />

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, this Keynesian logic made possible<br />

spending on large social programs and the investment in infrastructure.<br />

Business and the wealthy paid large marginal tax rates as opposed to the poor,<br />

working, and middle classes. This form of redistribution that allowed<br />

working people and even entire regions of the country to migrate to<br />

improved living conditions and to enjoy improved social services and public<br />

goods.<br />

Arguments were often made about the degree to which these taxes were<br />

indeed progressive. Political élites—more often than not representatives of<br />

business interests—made the argument time and again that a reduction of<br />

taxes would mean an increase in economic growth and productivity (a rise in<br />

GDP). However, such political arguments had very little support. First, there<br />

was the problem of politics. Americans overwhelmingly supported progressive<br />

taxation since the majority of them benefited from it directly. But next, the<br />

few studies that were made on the link between taxation and economic<br />

growth showed that there was no relationship at all. 4 Anti-tax political<br />

rhetoric therefore lacked, through the 1950s and 1960s and well into the<br />

1970s, any political support from the citizenry of the United States and also<br />

any empirical support from the social science establishment.<br />

This situation began to change in the late 1970s. For one thing, as American<br />

workers began to prosper they also started moving up in income tax brackets<br />

and getting hit by increasingly higher tax rates. This was part of the system’s<br />

design, and it also showed the old system was actually working. Tax revenues<br />

were supposed to grow automatically since “as the economy expanded,<br />

inflation pushed more and more individuals into higher and higher tax<br />

brackets as their nominal incomes increased.” 5 The tax system that had been<br />

devised and implemented in the 1950s and early 1960s began to lose its<br />

redistributive impact since the classes that, in the past, had benefited from<br />

the redistribution of wealth were now being taxed at ever higher rates and the<br />

<strong>Logos</strong> 2.3 – Summer 2003

<strong>Michael</strong> J. <strong>Thompson</strong><br />

benefits were no longer as clear as they once were. The result was a sharp<br />

increase in political pressure toward tax reform which, with the election of<br />

Ronald Reagan in 1980, led to a wholesale redirection of American<br />

government and its tax policies from the weakening of government agencies<br />

such as Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to an expanded federal<br />

deficit and the start of a widening gap in income and wealth that continues<br />

to grow today.<br />

The economic facts were merely an entrée for neoconservatives to argue their<br />

case for the minimal state and the reduction of taxes on corporations and the<br />

wealthy. Tax reform was necessary, but not the sort of draconian cuts in<br />

public services and institutions that served the working poor that were<br />

inevitably enacted. Instead of a reworking of increasingly complex tax codes<br />

and regulations, tax cuts were initiated that helped exacerbate inequalities<br />

that were growing from the impacts of a post-industrial economy. What the<br />

conservatives of the “Reagan Revolution” did was to focus opportunistically<br />

on public dissatisfaction about growing tax burdens created by a system that<br />

was in need of reform and use this public sentiment to trample the welfare<br />

state.<br />

On the whole, the statistical data is clear for anyone who has any casual<br />

acquaintance with the econometric studies and economic data: since 1980,<br />

there is a statistically significant relationship between the level of taxation and<br />

economic growth: as taxes increased, economic performance lessened in terms<br />

of GDP growth. This situation changed from the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s<br />

because there was a reconfiguration of global capitalism. From the 1980s<br />

onward, there was an increased global mobility of capital and the result was<br />

that corporations were able to move spatially to avoid costs. Taxes were<br />

among these costs. By 1990, this was a general theory of business planning<br />

with <strong>Michael</strong> Porter’s book, The Competitive Advantage of Nations, serving as<br />

one of the central texts coaching businesses in how to avoid the costs of<br />

producing in only one site, especially a site that was not “friendly” to business<br />

in terms of tax rates and regulatory limitations. Corporations were<br />

encouraged to move to places where the tax burden—as well as wages and<br />

other limitations—were less prohibitive to profits. In the United States, this<br />

meant moving many factory jobs out of the northeastern states, where labor<br />

unions were strong and businesses taxes were higher at the state and local<br />

levels, to the south or to other countries (i.e., Mexico).<br />

<strong>Logos</strong> 2.3 – Summer 2003

<strong>Michael</strong> J. <strong>Thompson</strong><br />

As the global economy began to change, the political economy of American<br />

taxation began to change as well. But this is where the crucial issue arises:<br />

even though there clearly were economic pressures brought on by this<br />

restructuring and the American tax system was in need of reform to remain a<br />

viable method of redistribution, the political reality was something quite<br />

different. The populist cry for tax reform was translated by the Reagan<br />

administration into a project of restructuring the state—a project which is<br />

still ongoing—where the role of the state in providing services was bypassed<br />

in favor of privatization and the redistributive functioning of taxation was<br />

rolled back. Legitimate needs for tax reform were therefore twisted by<br />

conservatives in an attempt to reorganize government and transform<br />

American democracy.<br />

Redefining and Restructuring American Democracy<br />

In 1843, the German economist Wilhelm Roscher wrote that political<br />

economy is not merely the “art of acquiring wealth; it is a political science<br />

based on evaluating and governing people.” 6 Economics is therefore a field<br />

that is fundamentally concerned with the very idea of the public good, it is<br />

far from being a value-free science. This is something that has been lost in<br />

recent debates on the politics of the Bush tax cut. The assumption—or even<br />

the outright belief—remains that there are legitimate economic reasons that<br />

can justify the various tax cuts which, and this is usually openly admitted,<br />

explicitly favor the wealthy. Inequalities that are generated from the tax cuts<br />

are considered “justifiable” first on supposedly economic grounds (i.e.,<br />

promoting growth and employment) and, at times, on ethical grounds, in the<br />

sense that everyone deserves to keep whatever they “earn.” But neither of<br />

these contentions actually make sense. No empirical evidence links tax cuts<br />

on wealthier income earners and employment, nor is there any reliable<br />

evidence that supports a link between tax cuts on individual income and<br />

economic growth, even if there is evidence, as was discussed above, that<br />

corporate tax rates do affect growth rates. Economic policy is being done for<br />

political ends and the actual content and intention of this politics needs to be<br />

seen for what it is: a reconfiguration of American democracy. This<br />

reconfiguration means a retreat from the idea that the state ought to<br />

meliorate class differences, the acceptance of the idea that political democracy<br />

is somehow indifferent to economic and social inequality, and toward a<br />

situation where the market extends to almost every aspect of public life.<br />

<strong>Logos</strong> 2.3 – Summer 2003

<strong>Michael</strong> J. <strong>Thompson</strong><br />

It is interesting to note that the Bush administration openly admits that its<br />

tax cuts favor the wealthy. This is a marked change from even twenty years<br />

ago when the political theorist Philip Green could write that “[s]pecial<br />

advantages for economic élites, as in the United States tax code, are<br />

introduced sub rosa, never proclaimed out loud. No one defends legislation<br />

by suggesting that the better class should be rewarded more and the inferior<br />

class less.” 7 Today, there has been a shift in the political sensitivity to social<br />

inequality and class division.<br />

It is a specific political philosophy, or ideology, that essentially defines the<br />

Bush tax cuts. The Bush administration’s economic argument that the tax<br />

cuts will somehow stimulate a dragging economy and increase employment<br />

has little support in theory and no support empirically. The tax cuts are<br />

proposed as part of a stimulus package, one that will promote economic<br />

growth. But, as James K. Galbraith has recently pointed out, these cuts are<br />

not a growth policy for two crucial reasons: “They are targeted to the<br />

wealthy, and they are back-loaded so as to conceal their true long-term<br />

impact on budget deficits.” 8 The extent of the tax cuts is therefore structured<br />

so that the real effects on the budget will not show up for another ten years or<br />

so since tax cuts on the wealthy will continue to diminish tax revenues and<br />

therefore increasingly bankrupt the state. Of course, this is not obvious when<br />

one examines the tax plan since such easily perceived hardship would cause at<br />

least a small degree of backlash.<br />

It is well-known economic logic that growth could be stimulated by new and<br />

increased government spending, something that has not even been publicly<br />

debated by the Bush administration’s economic policy advisors. This is<br />

because it would put the United States back in a Keynesian policy state of<br />

mind; and this means that there would be legitimacy in refunding the state<br />

and this would give some weight to political interests that want to expand the<br />

welfare state, government programs, regulatory agencies and other things<br />

which would be antithetical to the pro-business mentality and interests of the<br />

neoconservative agenda. In other words, once the state becomes more active<br />

in the economy, there is more likelihood that that state will also be used for<br />

expanding social programs. This runs directly counter to the current trend of<br />

shrinking the state and its influence in both economy and society.<br />

There is also the question of economic growth and job creation. This issue<br />

has been at the core of the Bush administration’s arguments for the tax cuts<br />

<strong>Logos</strong> 2.3 – Summer 2003

<strong>Michael</strong> J. <strong>Thompson</strong><br />

as well as a broad conservative wave of support. Heritage Foundation<br />

economist Mark Wilson claimed in a recent study that if the tax cuts were<br />

made retroactive to the beginning of 2003, 1.6 million jobs would be added<br />

to the economy by 2011 and expand economic output by another $248<br />

billion. 9 But there have been no academic economists who have been able to<br />

verify these findings in a single peer reviewed professional journal, and it is<br />

little surprise why. The rationale is classic “supply-side” economic thinking:<br />

the more money that is poured into the economy by letting people keep what<br />

they earn—so the supply-siders argue, in theory of course—the more society<br />

as a whole will benefit since people—especially the wealthy—will be more<br />

likely to invest in the economy and start new enterprises. A “free” market<br />

liberated from any type of restraint, regulation and public accountability is<br />

therefore the optimal arrangement for liberty and democracy. 10 This is the<br />

essential view that informs neoconservative political and social thought, but it<br />

is not a fact of economic science. Recall 1993 when there was an increase in<br />

the top income tax rate from 33 percent to 39.6 percent and still there was an<br />

increase in capital investment and a flourishing economy throughout the<br />

remainder of the 1990s. From the point of view of empirical evidence, the<br />

conservative argument quite simply makes no sense.<br />

It is more correct to say, then, that there is a political imperative behind this<br />

shift in economic policy, and its agenda is the fundamental transformation of<br />

American democracy as we have known it throughout the post-war period.<br />

The primary motivation is the ideological view that the state needs to be<br />

reduced, to be minimized. The conservative economist Robert Barro of<br />

Harvard University and the Hoover Institution put it most bluntly:<br />

One attraction of tax cuts and deficits is that they starve the<br />

government of revenue and thereby promote spending<br />

restraint. This worked particularly well in the 1980s. The<br />

Reagan tax reductions were a proclamation that the growth<br />

in government had to stop—and, with something of a lag,<br />

that happened from the mid-1980s through the 1990s. . . .<br />

[M]ost people’s income comes from their skill and effort<br />

(or, through inheritance, from the skill and effort of their<br />

parents). People deserve to keep most of what they have<br />

produced and earned, after sharing reasonably in the tax<br />

burden for financing a limited government. 11<br />

<strong>Logos</strong> 2.3 – Summer 2003

<strong>Michael</strong> J. <strong>Thompson</strong><br />

In many ways, Barro’s comment outlines in brief the basic ideology behind<br />

the politics of the tax cuts. The starving of the state is part and parcel of a<br />

political philosophy that sees an increase in the extent to which the market—<br />

and therefore not public, but private interests—control many, if not most, of<br />

the production and supply of public goods and services (school vouchers are<br />

one example of this). But the reality of the implications of a social policy<br />

driven by low taxes is never highlighted by any of these thinkers or writers.<br />

Take California, a state that passed Proposition 13 in 1978 which says that<br />

property taxes cannot be greater than 1 percent of the actual sales price on<br />

real estate with a limited increase of 2 percent per year. Although the tax was<br />

clearly something that most homeowners supported—and still do, it still has<br />

a support rating of 60 percent in the state—the benefits flowed to<br />

corporations whose property taxes on land and buildings are under-assessed<br />

and therefore drain the state, and its municipalities, of essential tax dollars. 12<br />

California now faces a $38 billion deficit and its public services have<br />

suffered—its schools are consistently ranked in the bottom half of the nation<br />

when it comes to spending per-student.<br />

Why people accept this situation is a crucial question that needs to be asked.<br />

For one thing, there is an ideological explanation. Taxes themselves are not<br />

seen as public goods and services, but as redistributive mechanisms to those<br />

that do not deserve it—i.e., the poor—or as funding an ever-expanding state<br />

and government waste. This is, in part, the product of the rhetoric of the<br />

Reagan administration and its attack on welfare. But there has also been a<br />

general consensus in the media—one that has become almost universally<br />

accepted—that government programs are inherently inefficient and never<br />

benefit those that they intent to help. This negative view of government<br />

programs is partly due to a certain ideology that has been nurtured by<br />

conservative think tanks, writers and politicians for more than three decades.<br />

In this sense, the middle class in America sees fewer of its interests in<br />

common with the lower class, even though this is clearly not the case. 13<br />

As this divide has increased—especially as the racialization of this divide also<br />

has increased—the largely white middle class sees the social cost of promoting<br />

more equality through taxation as increasingly unfair since it sees itself as<br />

shouldering much of this burden, never mind the fact that the middle class,<br />

too, has been affected by falling incomes and will increasingly see a slide in<br />

their own quality of life and the public institutions around them. This<br />

ideological explanation translates into a political reality where the lower<br />

classes are largely disenfranchised and the middle and upper classes would<br />

<strong>Logos</strong> 2.3 – Summer 2003

<strong>Michael</strong> J. <strong>Thompson</strong><br />

prefer to keep their incomes safe from taxation and have little interest in an<br />

increase in social equality and do not see the deteriorating quality of their<br />

public services as being connected with dwindling tax revenues. Either way,<br />

this cleavage between the lower and middle classes is politically debilitating<br />

since the Democratic Party sees its traditional constituency of the working<br />

poor and middle class workers with divergent political interests even though<br />

they have more in common with each other than either of them do with the<br />

wealthy. The fact is that fighting for improved public services and worker<br />

protections of all kinds are things that both the working poor and the middle<br />

class share as common interests. The problem remains articulating a political<br />

message that bridges this divide.<br />

This reorientation of American democracy puts markets and private interest<br />

over that of the public interest. Indeed, this has been the mainstay of<br />

American public life, but the new phase of this trend threatens to make it a<br />

more permanent reality. The reality of this situation can be seen most<br />

explicitly in the rise in economic inequality in the United States. The income<br />

tax was started in 1914 as a “class tax,” one that took from the wealthy and<br />

redistributed to the rest of society. This turned into a “mass tax” during the<br />

Second World War to accrue monies for the war effort. However, it is<br />

precisely the notion of class that has been allowed to drop out of the<br />

discussion. Class is at the center of the tax cut debate because, as Barro<br />

incorrectly states, it is not the case that wealthy people are the ones that<br />

“produce” and therefore “earn” what they receive in terms of income.<br />

Capitalism is an economic system that produces profits from social labor; the<br />

fact that corporate CEOs make more than 400 times the income of the<br />

workers that actually produce the products and services can hardly be<br />

justified through an argument based along the lines of earning one’s pay.<br />

This may be an extreme example, but all one needs to do is look at any<br />

corporation that develops, say, new technologies. Most, if not all, new<br />

technologies are developed in labs and research departments by Ph.D.s or<br />

other highly-skilled researchers earning middle income salaries whereas<br />

owners earn profits and income that are exponentially higher.<br />

What this discussion points to is that the very meaning of democracy in<br />

America is being transformed, perhaps transmogrified is a better term. In<br />

place of public concerns and the public interest, it is private interest that has<br />

now become paramount in social policy. Whereas the general character of the<br />

American welfare state in the post-war period implicitly recognized that<br />

political democracy and political equality are practically meaningless without<br />

<strong>Logos</strong> 2.3 – Summer 2003

<strong>Michael</strong> J. <strong>Thompson</strong><br />

some degree of economic equality and that capitalism as an economic system<br />

had serious deleterious effects on society, we now see an institutional<br />

transformation where the welfare state is being rolled back to allow the<br />

market once again—as in the 19th century—to operate freely irrespective of<br />

its social costs. The peculiar caste of American liberalism has typically been<br />

seen as strongly Lockean: private property and the ability to accumulate<br />

property indefinitely and, therefore, wealth, has always been its backbone.<br />

But there have also been other aspects of liberalism: those that stood up for<br />

the unpropertied and those whose interests were not served by the free<br />

activities of those who owned private property. Indeed, the expansion of<br />

American liberalism came not—as neoconservatives have been arguing in<br />

recent years—from the ability of individuals to own property and pursue an<br />

“American dream,” but rather from labor unions and working people that<br />

pushed for democratic reforms in the economy, the state and society. 14<br />

Democracy is now being translated into a laissez-faire libertarian reality: as<br />

the organization of the entirety of society around the pivot of self-interest<br />

subject to minor legal restraints by a minimal state.<br />

Bankrupting the state is therefore a primary aim of the conservative<br />

revolution. The very core of any substantive democracy, the public sphere,<br />

has slowly eroded through the further separation between state, society and<br />

economy, a separation made initially by Locke and then intensified by<br />

revolutionary thinkers like Thomas Paine. But American democracy was not<br />

initially grounded in Lockean notions of liberalism as writers such as Louis<br />

Hartz have insisted. Rather, it was the tradition of republicanism that<br />

informed the American Revolution and the early vision of the kind of<br />

democracy and society that it would usher in. In this sense, American<br />

democracy was initially concerned with the preservation of the public good<br />

through political institutions that were publicly accountable; it was not selfinterest<br />

and the accumulation of private property that initially informed<br />

broad sections of the American citizenry. But throughout American political<br />

history, there has been a real tension between this tradition of republicanism<br />

and its emphasis on the public good and Lockean liberalism that places<br />

emphasis on private property and a liberal political order insisting on the<br />

separation the political and economic spheres. Thinkers like William Graham<br />

Sumner in the 19th century and, more recently, Milton Friedman, have<br />

interpreted American democracy through the lens of individual liberty and,<br />

therefore, as economic and political liberalism, a position grounded in the<br />

individual and not in a conception of the public.<br />

<strong>Logos</strong> 2.3 – Summer 2003

<strong>Michael</strong> J. <strong>Thompson</strong><br />

Progressive alternatives to the tax cuts need to be articulated. A tax system<br />

that is as indecipherable and impenetrable as that in the United States<br />

requires serious reform. However, this does not mean eliminating tax<br />

revenues through tax cuts. Taxes on wealth would be much more effective<br />

than taxes on income since inequality has risen most in terms of wealth and<br />

not in terms of income. 15 In this way, the place where social inequality is<br />

most intense—in the unequal distribution of wealth—would be the place<br />

where redistribution would be concentrated. Wealth inequality between<br />

households means a disparity in the ability to buy a home, is more “likely to<br />

be better able to provide for its children’s educational and health needs, live<br />

in a neighborhood characterized by more amenities and lower levels of crime,<br />

have greater resources that can be called upon in times of economic hardship,<br />

and have more influence in political life.” 16<br />

But even more, the central problem—and one that would no doubt capture<br />

the attention of much of the electorate—would be to advocate job growth<br />

through government stimulus. What the Democrats in Washington should<br />

be pushing for in place of simply smaller tax cuts is an expansion in<br />

government programs that provide both public services and employment.<br />

Education, health care as well as transportation infrastructure are specific<br />

examples. Aside from being excellent opportunities for the state to create<br />

useful and dearly needed public services, they would also create well-paying<br />

jobs for large segments of the population. These are programs that have<br />

actually worked in the past and today require more serious attention in part<br />

because they are in stark opposition to the supply-side policies that the Bush<br />

administration has been pushing. Indeed, the empirical evidence for job<br />

growth resulting from increased consumer spending is extremely weak<br />

compared to that of state and federal programs. 17<br />

A responsible left program needs to counter the ideology that currently<br />

hampers economic policy and move toward policies that will capture the<br />

interests of working people and connect their concerns with broader public<br />

programs at the state and federal level. This has not happened for a variety of<br />

reasons, one of which can be located in the general ideological view of the<br />

contemporary left and its attitude toward the state. In many ways, this is a<br />

product of the 1960s and the New Left which was overtly hostile toward the<br />

state. From anarchist-inspired movements to the Arendtians and the<br />

emphasis on communitarianism over what was generally seen as the<br />

coerciveness of the state—all of which were quite respectable positions on the<br />

left in the 1960s—the New Left promulgated a general political view that<br />

<strong>Logos</strong> 2.3 – Summer 2003

<strong>Michael</strong> J. <strong>Thompson</strong><br />

was in opposition to the state, not merely in practice, but in theory as well. 18<br />

The New Left’s attack on the state left liberal Democrats with few allies when<br />

conservatives took power in 1980 with their own anti-state agenda. The state<br />

programs of the Roosevelt and Johnson administrations seem utopian now in<br />

the present context and the left has itself to blame in part for the lack of<br />

political and ideological support for the state and it has no practical<br />

institutional alternatives to the neoconservative vision that is emerging as<br />

present reality.<br />

Even more, there was also—beginning in the early 1970s—an effort by big<br />

business to clamp down on labor unions and also begin a campaign of<br />

political activism themselves to help stem the tide of anti-business sentiment<br />

whipped up during the 1960s. This is where institutions such as the<br />

American Enterprise Institute, the Cato Institute and the Heritage<br />

Foundation got started and by the end of the decade, they had succeeded in<br />

electing a president with their own ideological perspective.<br />

As a result of these different political trends, the Bush tax cuts will be able to<br />

push further a liberalized economic order that at the same time promotes<br />

economic inequality and the concentration of power in the hands of the few<br />

at the expense of the many, whether it be through wealth, property, or media<br />

control. This agenda goes against the grain of much of Western political<br />

thought which constantly repeats the injunction against extreme inequalities<br />

in property and wealth. From Plato and Aristotle through Locke, Smith,<br />

Hegel, Tocqueville and Dewey, among so many others, gross social<br />

inequalities have been seen as a major threat to the common good and a<br />

democratic polity. More and more, the republican strain in American politics<br />

is being eroded and the move toward a democracy based on the foundation<br />

of private interest is being increasingly privileged. Such a reconfigured<br />

democracy will see the roll back of the institutions and policies that have<br />

helped those disadvantaged by the economy; it will increase economic<br />

inequalities as well as inequalities in quality of life; and, in the end, it will<br />

affect the way that political power is distributed in the United States. The<br />

Bush tax cuts are therefore more complex and even more dangerous than<br />

initially meets the eye, and it is the very structure of American democratic<br />

culture and governance that hangs in the balance.<br />

<strong>Logos</strong> 2.3 – Summer 2003

<strong>Michael</strong> J. <strong>Thompson</strong><br />

Notes<br />

1 Grover Norquist on NOW in conversation with Bill Moyers, transcript at:<br />

http://www.pbs.org/now/printable/transcript_norquist_print.html. It must<br />

be said that there is also a bit of hysteria mixed in with this rhetoric. Norquist<br />

again: “Guys with guns will show up if you don’t pay your taxes and take<br />

that money from you. And I think that we want in order to have a free<br />

society to have as little as possible done coercively.” (Ibid.)<br />

2 David Cay Johnston, “Very Richest’s Share of Income Grew Even Bigger,<br />

Data Show,” The New York Times, June 26, 2003.<br />

3 See Laura D’Andrea Tyson, “Tax Cuts for the Rich Are Even More Wrong<br />

Today,” Business Week Online at:<br />

http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/02_27/b3790053.htm.<br />

4 See Claudio Katz, Vincent Mahler and <strong>Michael</strong> Franz, “The Impact of<br />

Growth and Distribution in Capitalist Countries: A Cross National Study,”<br />

American Political Science Review, vol. 77, no. 4, 1983.<br />

5 Sven Steimo, “Why Tax Reform? Understanding Tax Reform in its Political<br />

and Economic Context,”<br />

http://stripe.colorado.edu/%7Esteinmo/reform.html.<br />

6 Grundrisse zu Vorlesungen über die Staatswirtschaft quoted in George E.<br />

McCarthy, Classical Horizons: The Origins of Sociology in Ancient Greece<br />

(Albany: SUNY Press, 2003).<br />

7 The Pursuit of Inequality, p. 3 (New York: Pantheon Books, 1981).<br />

8 “Socking It to the States,” p. 12 The Nation, June 9, 2003.<br />

9 See David Francis, “Bush Tax Cuts Widen US Income Gap,” The Christian<br />

Science Monitor and Common Dreams at:<br />

www.commondreams.org/headlines01/0523-02.htm.<br />

10 Of course, there really is no such thing as a truly free market since there is<br />

always some form of corporate welfare or tariffs that benefit corporations.<br />

The key issue that should be emphasized is that any regulation that<br />

potentially helps working people is attacked whereas those regulatory bodies<br />

and policies that help capital are promoted or maintained.<br />

11 “There’s A Lot to Like About Bush’s Tax Plan,” p. 28, Business Week,<br />

February 24, 2003.<br />

12 See Mark Baldassare, “How the West Is Taxed,” Op-Ed Section The New<br />

York Times, June 27, 2003.<br />

13 See William Julius Wilson, The Bridge Over the Racial Divide: Rising<br />

Inequality and Coalition Politics (Berkeley: University of California Press,<br />

1999).<br />

<strong>Logos</strong> 2.3 – Summer 2003

<strong>Michael</strong> J. <strong>Thompson</strong><br />

14 For an excellent statement of this position, see Karen Orren, Belated<br />

Feudalism (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991).<br />

15 See Edward N. Wolff, Top Heavy: The Increasing Inequality of Wealth in<br />

America and What Can Be Done About It (New York: The New Press, 2002).<br />

16 Edward N. Wolff, “Racial Wealth Disparities,” p. 7 Jerome Levy Institute of<br />

Economics Public Policy Brief, no. 66, 2001.<br />

17 See Jeff Madrick “Economic Scene,” The New York Times, July 10, 2003.<br />

18 Sadly, this is still a thriving view among leftist thinkers. See the recent<br />

“Rosa Luxemburg Debate” concerning the state in New Politics, vol. VIII,<br />

2002 no. 4; vol. IX, 2002, no. 1 and no. 2.<br />

<strong>Michael</strong> J. <strong>Thompson</strong> is the founder and editor of <strong>Logos</strong> and teaches Political<br />

Science at Hunter College, CUNY. His new book, Islam and the West: Critical<br />

Perspectives on Modernity, has just been released from Rowman and Littlefield<br />

Press.<br />

<strong>Logos</strong> 2.3 – Summer 2003

L<br />

<strong>Stephen</strong> <strong>Eric</strong> <strong>Bronner</strong><br />

American Landscape: Lies, Fears, and the<br />

Distortion of Democracy<br />

by<br />

<strong>Stephen</strong> <strong>Eric</strong> <strong>Bronner</strong><br />

ying has always been part of politics. Traditionally, however, the lie was<br />

seen as a necessary evil that those in power should keep from their<br />

subjects. Even totalitarians tried to hide the brutal truths on which their<br />

regimes rested. This disparity gave critics and reformers their sense of<br />

purpose: to illuminate for citizens the difference between the way the world<br />

appeared and the way it actually functioned. In the aftermath of the Iraqi<br />

War, however, that sense of purpose has become imperiled along with the<br />

trust necessary for maintaining a democratic discourse. The Bush<br />

administration has boldly proclaimed the legitimacy of the lie, the irrelevance<br />

of trust, while the mainstream media has essentially looked the other way.<br />

Not since the days of Senator Joseph McCarthy has such purposeful<br />

misrepresentation, such blatant lying, permeated the political culture of the<br />

United States. It has now become clear to all except the most stubborn that<br />

the justification for war against Iraq was not simply based on “mistaken”<br />

interpretations, or “false data,” but on sheer mendacity. Current discussions<br />

among politicians and investigators focus almost exclusively on the false<br />

assertion made in sixteen words of a presidential speech that Saddam sought<br />

to buy uranium for his weapons of mass destruction in Africa. The forest has<br />

already been lost for the trees. It has all become a matter of faulty intelligence<br />

by subordinates rather than purposeful lying by those in authority. CIA<br />

officials have, however, openly stated that they were pressured to make their<br />

research results support governmental policy. Secretary of State Colin Powell<br />

has still not substantiated claims concerning the existence of weapons of mass<br />

destruction that he made in his famous speech to the United Nations. Other<br />

important members of the Bush inner circle have openly admitted that that<br />

the threat posed by Iraq was grossly exaggerated even though emphasizing it<br />

served to build a consensus for war. They have nonchalantly verified what<br />

critics have always known: that American policy was propelled by thoughts of<br />

<strong>Logos</strong> 2.3 – Summer 2003

<strong>Stephen</strong> <strong>Eric</strong> <strong>Bronner</strong><br />

an Iraqi nation “swimming in oil,” control over four rivers in an arid region,<br />

throwing the fear of the western God into Teheran and Damascus, and<br />

establishing an alternative military presence to what once existed in Saudi<br />

Arabia. The Bush administration has chastised none of them and criticisms<br />

by politicians stemming from the Democratic Party have been tempered to<br />

the point of insignificance. “Leaders” of the so-called opposition party<br />

obviously fear being branded disloyal.<br />

As they quake in their boots and wring their hands, however, issues<br />

concerning the broader justification of the war have disappeared entirely<br />

from the widely read right-wing tabloids like The New York Post and, at best,<br />

retreated to the middle pages of more credible newspapers. Enough elected<br />

politicians in both parties, scurrying for cover, now routinely make sure to<br />

note that their support for the war did not rest on the existence of weapons of<br />

mass destruction in Iraq. Rarely mentioned is that the lack of such weapons,<br />

combined with the inability to find proof of links between Saddam Hussein<br />

and Al Qaeda, invalidates the claim that Iraq actually posed a national<br />

security threat to the United States. Everyone in the political establishment<br />

now points to humanitarian motives. For the most part, however, such<br />

concerns were not upper-most in their minds then and there is little reason to<br />

believe that they believed them decisive for the public opinion of the<br />

American public: human rights indeed became championed by self-styled<br />

“realists” like Paul Wolfowitz and Henry Kissinger—whose reputations were<br />

previously based on denying them—only when claims concerning the<br />

imperiled national interests of the United States were revealed as vacuous.<br />

President Bush and members of his cabinet may now insist that the weapons<br />

will ultimately be found, with luck perhaps just before the next election, and<br />

the links to Al Qaeda will soon be unveiled. But this is already to admit that<br />

the evidence did not exist when the propaganda machine began to roll out its<br />

arguments for war. The administration had untold intellectual resources from<br />

which to learn that the United States would not be welcomed as the liberator<br />

of Iraq and that serious problems would plague the post-war reconstruction.<br />

But the administration wasn’t interested: it was content to forward its<br />

position and then find information to back it up. This indeed begs two<br />

obvious questions that are still hardly ever asked by the mainstream media:<br />

Would the American public have supported a war against Iraq under those<br />

circumstances and, perhaps more importantly, did this self-induced ignorance<br />

about conditions in Iraq help produce the current morass in which billions of<br />

<strong>Logos</strong> 2.3 – Summer 2003

<strong>Stephen</strong> <strong>Eric</strong> <strong>Bronner</strong><br />

dollars have been wasted and, seemingly every day, another few young<br />

American soldiers are being injured or killed?<br />

Millions of dollars were wasted by a special prosecutor on investigating false<br />

allegations of financial impropriety by Bill and Hillary Clinton.<br />

Impeachment proceedings were begun following the revelations of an affair<br />

between the then president and an intern. The media was up in arms and its<br />

champions still pat themselves on the back for their role in bringing about<br />

the Watergate hearings. When it comes to the chorus of untruth perpetrated<br />

over Iraq, which brought a nation into war with the resulting loss of lives and<br />

resources, it seems the public interest is best served by “bi-partisan”<br />

committees and a submissive press. Just as the Republican Party has been<br />

flagrant in its refusal to rationally justify its war of “liberation,” which is<br />

leaving an increasingly sour taste in the mouths of occupiers and occupied<br />

alike, the centrist Democratic Leadership Council made famous by Bill<br />

Clinton is now warning the public that—with the recent surge in the polls of<br />

Governor Howard Dean—its party is on the verge of being taken over by a<br />

“far left” intent upon opposing tax cuts, introducing “costly” social programs,<br />

and criticizing the foreign policy of the Bush administration.<br />

Leading members of the DLC poignantly ask whether the Democrats wish<br />

“to vent or govern” and when questioned whether the current disarray in<br />

which the party finds itself was a product of Republican success or<br />

Democratic blunders, Senator Evan Bayh of Indiana, chairman of the<br />

organization, responded that it was a matter of “assisted suicide.” Forgotten<br />

was the election of November 2002 in which, by every serious account, it was<br />

the inability of the Democratic Party to offer any meaningful alternative to<br />

the policy of President Bush that led to the most disastrous non-presidential<br />

year losses in American history. It doesn’t seem to matter that the “bipartisan”<br />

candidates like Joseph Lieberman, who refuse to offer a coherent<br />

alternative on domestic and foreign policy issues, are not catching on with<br />

the American public. It also doesn’t seem to matter that the proposed tax cuts<br />

work against the interests of the party’s own constituency, that social welfare<br />

programs would cost a fraction of the billion dollars a month spent in Iraq,<br />

and that the current foreign policy is undermining respect for the United<br />

States throughout the world. Ignored is the way in which the Democratic<br />

Party—the party of FDR, Bobby Kennedy, and Paul Wellstone—has become<br />

a joke on the mid-night talk shows. And, all the while, the “liberal” media<br />

nods its head and counsels prudence. Senator Bayh has no clue: as it now<br />

<strong>Logos</strong> 2.3 – Summer 2003

<strong>Stephen</strong> <strong>Eric</strong> <strong>Bronner</strong><br />

stands, the Democratic Party can neither “vent” nor “govern.” Democrats<br />

should worry about their image—especially since they don’t have one.<br />

The United States is ever more surely appearing less like a functioning<br />

democracy in which ideologically distinct parties and groups debate the issues<br />

of the day than a one-party state ruled by shifting administrative factions.<br />

Free speech exists, but to have a formal right and to make substantive use of<br />

it is a very different matter. Consensus and bi-partisanship are becoming<br />

increasingly paranoid preoccupations of the media whose range of debate is<br />

becoming narrowed to that between humpty and dumpty. Noam Chomsky<br />

may not be everyone’s taste, but his little collection of interviews 9-11 (New<br />

York: Seven Stories Press) was the best-selling work on that terrible event:<br />

when was the last time you saw him interviewed on mainstream media? It is<br />

the same with Barbara Ehrenreich, Frances Fox Piven, and any number of<br />

other radical or progressive public figures. Every now and then, of course,<br />

Cornel West may pop up for an interview on MSNBC, there are still a few<br />

critical editorialists like Paul Krugman in The New York Times and Robert<br />

Scheer in The Los Angeles Times, and Sean Penn can still pay for a full page<br />

advertisement to express his critical views on the war. Nevertheless, their<br />

voices are being drowned out by the right-wing pundits that dominate what<br />

conservatives—ever ready to view themselves as the victim of the system they<br />

control—castigate as the “liberal” media.<br />

The situation brings to mind the vision of a society dominated by what<br />

Herbert Marcuse once termed “repressive tolerance”: a world in which<br />

establishmentarians can point to the rare moment of radical criticism to<br />

better enjoy the reign of an overwhelming conformity. The evidence is<br />

everywhere: CNN is only a minor player when compared with the combined<br />

power of television news shows with huge audiences hosted by megacelebrities—still<br />

relatively unknown in Europe—like Rush Limbaugh, Bill<br />

O’Reilly, and Pat Robertson. Belief in the reactionary character of the<br />

American public has generated a self-fulfilling prophecy: the public gets the<br />

shows it wants that, in turn, only strengthen the original prejudices. Edward<br />

R. Murrow, so courageous in his resistance to the hysteria of the 1950s, may<br />

often be invoked by the “fourth estate,” but that invocation is merely<br />

symbolic.<br />

Hardly a word is said any longer about the skepticism of millions who<br />

participated in the mass demonstrations that rocked the United States or how<br />

the mainstream media criticism of Tony Blair has transformed the English<br />

<strong>Logos</strong> 2.3 – Summer 2003

<strong>Stephen</strong> <strong>Eric</strong> <strong>Bronner</strong><br />

political landscape. One criterion for judging democracy is the plurality of<br />

views presented to the public. That is because the number of views expressed<br />

usually reflects the number of political choices from which the public can<br />

choose. It is striking to reflect upon the range of perspectives expressed<br />

during the era of Progressivism, the New Deal, and the 1960s. By the same<br />

token, however, the attempt to constrict civil liberties in moments of crisis<br />

has been a fundamental trend of American history. Thus, in the current<br />

context, it is chilling to consider the narrowing of debate over the legitimacy<br />

of a terrible war to sixteen words made in a presidential speech, an<br />

increasingly corrupt evaluation of policy options, and a growing inability of<br />

the American public to grasp the distrust its present government inspires<br />

elsewhere.<br />

A current Pew Poll of more than forty-four countries, directed by former<br />

Secretary of State Madeline Albright, shows that distrust of the United States<br />

has grown in an exceptionally dramatic fashion in each of them. This<br />

includes sensitive nations like Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Indonesia<br />

where unfavorable ratings of the United States have gone from 36% in the<br />

summer of 2002 to 83% in May of 2003. The “streets” of Europe and, more<br />

importantly, the Arab world have been lost. Perhaps they will be regained at a<br />

future time. But the numbers in this poll express anger at a basic reality.<br />

With its new strategy of the “pre-emptive strike” buttressed by a $400 billion<br />

defense budget, bigger than that of the next eighteen nations put together,<br />

the United States has rendered illusory the idea of a “multi-polar world.” It<br />

has become the hegemon amid a world of subaltern states and it has no need<br />

to listen or debate. The difference between truth and falsehood no longer<br />

matter. There remains only the fact of victory, the fall of Saddam Hussein,<br />

and the bloated self-justifications attendant upon what Senator J. William<br />

Fulbright, the great critic of the Vietnam War, termed “the arrogance of<br />

power.”<br />

Americans have traditionally tended to rally around the president in times of<br />

war. But this war, according to the president, has no end in sight. A new<br />

department of “homeland security” is being contemplated and the civil<br />

liberties of citizens are imperiled. Justification is supplied by manipulative<br />

and self-serving “national security alerts” in which the designation of danger<br />

shifts from yellow to orange to red and then back again without the least<br />

evidence being presented regarding why a certain color was chosen and why<br />

it was changed. The bully pulpit of the president, as Theodore Roosevelt<br />

called it, can go a long way in defining the style of national discourse and a<br />

<strong>Logos</strong> 2.3 – Summer 2003

<strong>Stephen</strong> <strong>Eric</strong> <strong>Bronner</strong><br />

sense of what is acceptable to its citizenry. This is where leadership asserts<br />

itself. Nevertheless, precisely on this question of leadership for which<br />

President Bush has received such lavish praise, he is weakest.<br />

Beyond all social policy concerns, or disagreements over any particular issue<br />

of foreign policy, this president is presiding over a newly emerging culture in<br />

which truth is subordinate to power, reason is the preserve of academics,<br />

paranoia is hyped, and know-nothing nationalism is celebrated. No longer is<br />

the constructive criticism of genuine democratic allies taken seriously: better<br />

to rely on a corrupt “coalition of the willing” whose regimes have been<br />

bribed, whose economies have been threatened, and whose soldiers have been<br />

exempt from fighting this unending war on terror. There is little critical selfreflection<br />

and not the hint of an apology for its conduct in the weeks before<br />

the war broke out. It is dangerous to underestimate the moral high ground<br />

that has been squandered since 9/11. The question for other nations is this:<br />

how to trust the liar whose arrogance is such that he finds it unnecessary to<br />

conceal the lie?<br />

Democracy remains elusive in Iraq, and Afghanistan is languishing in misery<br />

while the creation of new threats to the national security of the United States<br />

is being undertaken right now. Iran trembles. Syria, too. And there is always<br />

Cuba or North Korea. The enemy can change in the blink of an eye. The<br />

point about arbitrary power is, indeed, that it is arbitrary. What happens<br />

once the next lie is told and the next gamble is made? It is perhaps useful to<br />

think back to other powerful nations whose leaders liked to lie and loved to<br />

gamble—and who won and won and won again until finally they believed<br />

their own lies and gambled once too often.<br />

<strong>Stephen</strong> <strong>Eric</strong> <strong>Bronner</strong> is Professor (II) of Political Science, German Studies and<br />

Comparative Literature at Rutgers University. A new edition of his book A<br />

Rumor About the Jews is forthcoming from Oxford University Press.<br />

<strong>Logos</strong> 2.3 – Summer 2003

T<br />

<strong>Wadood</strong> <strong>Hamad</strong><br />

Wither Independence?<br />

Iraq in Perspective: From Despotism to Occupation<br />

by<br />

<strong>Wadood</strong> <strong>Hamad</strong><br />

I<br />

here has been nearly unanimous consensus among Iraqis that a new age<br />

of possible progress and prosperity has dawned upon their battered and<br />

war-fatigued country with the downfall of Saddam Hussein on April 9 th .<br />

However, much had tainted this rosy image, and much more could still mar<br />

the outcome. A principal factor has been the highly incompetent and<br />

nonchalant manner in which the U.S.-U.K. occupying forces have conducted<br />

themselves: one wonders if this is a result of sheer imperial arrogance, or<br />

ignorance of the region, or a combination of both. None of the above reasons<br />

is excusable in any way, of course. When a disproportionate U.S. force<br />

decimated Saddam Hussein’s two infamous sons, Uday and Qusay, and their<br />

few companions and then showed their battered images to the world, two<br />

messages may be read therefrom. First, the U.S. will absolutely contravene<br />

every mode of rational, moral, ethical and reasonable behavior to make their<br />

point and achieve success (in their own assessment). Why did they not arrest<br />

these two criminals and have them justly tried in Iraqi courts? Second, U.S.<br />

policy planners have an inveterate attachment to change through force. The<br />

lessons from the 20 th century are aplenty (as the Hiroshima anniversary,<br />

amongst others, adequately reminds us), and the difference now is of volume<br />

and rate rather than quality.<br />

Those of us who vehemently opposed the launch of an immoral, unjust and<br />

illegal war have to seriously address now the occupation: not in a romantic,<br />

knee-jerk oppositional fashion—which has become commonplace among<br />

western as well as Arab oppositionists to U.S. imperialist plans—but in a<br />

calculated manner that puts the interests of the Iraqi people<br />

uncompromisingly at the forefront. Thus, what are the facts on the ground,<br />

and what may be done? In what follows, I am more interested in raising<br />

questions than providing simple, speculative answers. What deeply angers<br />

and pains me are the cold as well as condescending views offered by Arabs or<br />

<strong>Logos</strong> 2.3 – Summer 2003

<strong>Wadood</strong> <strong>Hamad</strong><br />

Americans, alike, when it comes to dealing with Iraq. To these two groups,<br />

governments and populace, Iraq seems to be a possession, and each has an<br />

opinion on what to do with it. Very little attention is given to the how to<br />

achieve results, which leads me, and a few others, to believe that none is really<br />

interested in the well-being of Iraqis.<br />

II<br />

The U.S. has waged the war against Iraq in spite of unprecedented<br />

worldwide public pressure against it. The pretexts for the war, Saddam<br />

Hussein’s possession of Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) and his<br />

alleged link to al-Qaeda, have been in dispute from the very beginning. Four<br />

months after the war and neither a trace of WMD exists, nor a hint of a link<br />

to al-Qaeda terrorists, rather an unraveling of a series of apocryphal stories<br />

penned by elected and unelected officials in the U.S. and U.K. governments<br />

with the sole purpose of manipulating public opinion prior to waging war.<br />

Now the sad fact is that such despicable tactics—and the list could be long—<br />

have placed the fallen despot, Saddam Hussein, and his regime in a rather<br />

romantic-heroic position among many a person within the Arab world, the<br />

third world and elsewhere. Rather than containing terrorist groups and<br />

cutting their lifelines, U.S. actions have given life to a litany of fragmented,<br />

but ruthless, reactionary groups intent on inflicting damage on all symbols of<br />

modernity—and certainly not limited to the U.S. and its interests.<br />

To this day, many cannot fathom the horrific and criminal nature of the<br />

deposed Iraqi regime; and U.S. tactics in Iraq have allowed people to<br />

compare to and contrast with a fictitious version of Saddam Hussein’s reign.<br />

Every visitor to Iraq speaks of war-torn cities, devastation, dilapidated services<br />

and war- and sanctions-fatigued populace, on the one hand, and the existence<br />

of monstrous, grand palaces and edifices, on the other: All being the direct<br />

outcome of 30+ years of authoritarian rule and 12 years of the most<br />

suffocating (U.S.-U.K. instigated and propelled) economic sanctions ever<br />

imposed. But Iraqis returning for the first time after decades of exile have<br />

observed one thing of significant importance in the midst of the rubble:<br />

people feel free and hopeful. There is a satisfying, inner happiness one feels<br />

when free that can only be understood if one’s freedom has been curtailed: no<br />

explanation, lengthy or terse, would do justice. This is what precisely gives<br />

<strong>Logos</strong> 2.3 – Summer 2003

<strong>Wadood</strong> <strong>Hamad</strong><br />

one hope for a better tomorrow. Alas, both are slowly being nibbled at, and<br />

the prospects are unclear.<br />

Four months after the fall of Saddam Hussein’s hierarchical structure of<br />

governance, basic municipal and civic services are at an appallingly low level.<br />

The work force has no work and only portion of it has started receiving<br />

salaries, some of which were given in useless currency that further aggravated<br />

an already drained populace. 1 Security is deteriorating mainly in Baghdad and<br />

environs, while most other cities function much better. Further, the rumor<br />

mill is grinding absolutely anything imaginable, which only contributes to<br />

increasing the level of uncertainty in the country. The Coalition Provisional<br />

Authority (CPA) promulgated actions that could only worsen a very<br />

unsettled situation, namely: dissolving the Army and affiliated organizations,<br />

as well as the Ministry of Information, thus rendering more than 250,000<br />

without recourse to any source of livelihood. Furthermore, the so-called<br />

process of de-Baathification is purely ideological in nature—principally<br />

fueled by the hawks in the U.S. Administration and their Iraqi underlings,<br />

most notably Ahmed Chalabi, Kanan Makiya and Co.<br />

In a country where membership to the Baath party became the only means<br />

for advancement for many, this tactic is bound to engulf the country in a<br />

process of vilification and counter-vilification based on personal, rather than<br />

objective, accounts. What would be more a appropriate and just recourse is<br />

to judiciously investigate the role of senior Baath functionaries: trying before<br />

the law all those guilty of crimes against the people, and pardoning those<br />

whose hands were untainted. A national heeling and reconciliation process is<br />

essential if the tragedies and horrors of the past 30 years are to be<br />

constructively addressed, and avoid institutionalizing recrimination and guilt<br />

by association. The latter is likely to take the country down a dangerous<br />

spiral, which accentuates antiquated tribal rule—that Saddam Hussein<br />

himself tried to resuscitate in the latter part of the nineties to further buttress<br />

his reign. Iraq’s political parties must resist this and instead press for just trials<br />

and a process of reconciliation. Interestingly, the majority of Iraqis seems to<br />

favor this approach as evinced by personal and televised accounts (albeit not<br />

polled scientifically), thus presenting yet another hopeful scenario for Iraq<br />

and its people if left alone.<br />

Events indicate that the U.S. invading-cum-occupying forces, while<br />

possessing formidable fire power, have seemingly less than formidable<br />

<strong>Logos</strong> 2.3 – Summer 2003

<strong>Wadood</strong> <strong>Hamad</strong><br />

planning and analytical powers. Most echelons of the decision-making<br />

process within the U.S. government had apparently been surprised by the run<br />

of events. More surprisingly, no contingency plans had been prepared for the<br />

(speedy) fall of Saddam Hussein’s government and the ensuing dissolution of<br />

ministries, state organizations, the police, etc. What would a rational person<br />

expect would happen if a highly centralized structure of governance<br />

dependent on a ruthless social policy grounded in chauvinistic and sectarian<br />

politics suddenly collapsed? Why, then, have U.S. planners and their research<br />

centers and institutes been unable to anticipate at least a general framework<br />

for dealing with events?<br />

The sanctions-fatigued, repressed Iraqis with hardly adequate access to basic<br />

food requirements, never mind super-dooper search engines, computing<br />

power, etc., could—and would—have done much better than the<br />

functionaries of the CPA. It is also worthy of note that this just-do-and-waitto-see-what-happens<br />

is essentially the same obscurantism governing<br />

doctrinaire religious teachings (of whatever color): a complete and utter<br />

absence of critical thought. This behavior fundamentally stems from what the<br />

U.S. feels itself to be: the unparalleled imperial power of our age. Thus,<br />

ideology is fundamentally and intrinsically at the core of all that is<br />

happening, and the media have performed a compelling job of disinforming<br />

the U.S. populace and effectively contributing to a brainwashing campaign at<br />

an astounding rate. A pressing question presents itself: Will the U.S. populace<br />

seek to change this through ballot boxes in 2004? Will they come to really<br />

understand that they would not be hated in the world if they actually<br />

thought of the rest of the world on an equal footing and genuinely divorced<br />

themselves from condescending attitudes that are so prevalent in almost every<br />

segment of class, profession, ethnic and religious background?<br />

III<br />

IRAQ IS BEING CONSTANTLY PORTRAYED AS A FRAGILE formation of ethnoreligious<br />

groups, essentially violent and vying for power. Is there a country on<br />

this planet that is not an amalgamation of ethno-religious groups? Even Israel<br />

as a Jewish State comprises various ethnicities, and hence is heterogeneous.<br />

Modern Iraq has been a staunchly secular country where the separation of<br />

religion from the state has been a fact of life—respected and adopted by all,<br />

<strong>Logos</strong> 2.3 – Summer 2003

<strong>Wadood</strong> <strong>Hamad</strong><br />

and certainly by its Shiite and Sunni religious establishments. While not a<br />

phenomenon at the popular level, ethno-sectarian chauvinism has been<br />

institutionalized by the state since its inception: the progeny of the British<br />

concocted Cox-al-Naqeeb plan laying down the foundation for the pyramidal<br />

power structure in the nascent government of Iraq in 1921. To ensure<br />

reliance on foreign forces, state power was entrusted to a minority elite, with<br />

a clear segregation of the largesse among the vying groups: Officers of the<br />

erstwhile Ottoman Army, Sunni landowners and religious notables, and a<br />

handful of Shiite landowners and religious notables and Jewish and Christian<br />

businessmen. 2 The association was entrenched in the belonging to a group,<br />

ethnic, religious or sectarian, rather than to the country Iraq. It may be moot<br />

to question whether that was not a reflection of the lack of a national<br />

identity; however, history indicates that the inhabitants of Iraq had strongly<br />

identified themselves with the land of Mesopotamia, and their association has<br />

since been with it rather than strictly speaking the tribe, or religion or sect.<br />

1958, marking the overthrow of the monarchy and the establishment of the<br />

first republic, ushered in a new period where Iraqis identified themselves as<br />

citizens and not according to tribal, religious or sectarian divides. The<br />

modern political formations, Communist or Pan-Arab—principally the<br />

Baath party, have been clearly secular and encompassed all sectors of society<br />

along ideological rather than ethno-sectarian divisions. The Baath party<br />

slowly degenerated since Saddam Hussein became the “strong man” in the<br />

early seventies, and in the summer of 1979 he consummated his power by<br />

annihilating the leftist wing within the party (led by Abdel Khaleq al-<br />

Samarai, who was summarily purged with more than 50 of his comrades,<br />

most of whom were executed by Saddam and his underlings). During the<br />

1980s Saddam Hussein embarked on entrenching a family-based rule, and<br />

the remnants of the party had become a façade to one of the darkest periods<br />

of Iraq’s history. In the 1990s, with the help of the sanctions, the government<br />

had further degenerated into a brutal mafia-style repression against any<br />

modicum of opposition. The inhabitants of the south, mostly Shias, paid a<br />

particularly heavy price as a result of their uprising following the 1991 Gulf<br />

War. Prior to 1991 the government had forcibly transferred Arabs from the<br />

south to the Kurdish north, especially oil-rich Kirkuk, with the objective of<br />

creating a new demographic reality. Moreover, a diligent student of the<br />

British colonizers, Saddam Hussein fervently adopted an approach favoring<br />

one or other Sunni clan for wealth and governmental positions, and<br />

continually pitted one tribe against the other. This ipso facto created a<br />

<strong>Logos</strong> 2.3 – Summer 2003

<strong>Wadood</strong> <strong>Hamad</strong><br />