TORAH

12gwXwFFX

12gwXwFFX

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

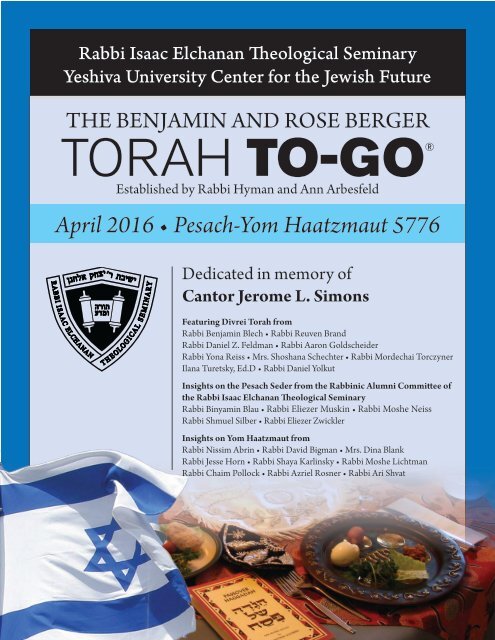

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary<br />

Yeshiva University Center for the Jewish Future<br />

THE BENJAMIN AND ROSE BERGER<br />

<strong>TORAH</strong> TO-GO®<br />

Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld<br />

April 2016 • Pesach-Yom Haatzmaut 5776<br />

Dedicated in memory of<br />

Cantor Jerome L. Simons<br />

Featuring Divrei Torah from<br />

Rabbi Benjamin Blech • Rabbi Reuven Brand<br />

Rabbi Daniel Z. Feldman • Rabbi Aaron Goldscheider<br />

Rabbi Yona Reiss • Mrs. Shoshana Schechter • Rabbi Mordechai Torczyner<br />

Ilana Turetsky, Ed.D • Rabbi Daniel Yolkut<br />

Insights on the Pesach Seder from the Rabbinic Alumni Committee of<br />

the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary<br />

Rabbi Binyamin Blau • Rabbi Eliezer Muskin • Rabbi Moshe Neiss<br />

Rabbi Shmuel Silber • Rabbi Eliezer Zwickler<br />

Insights on Yom Haatzmaut from<br />

Rabbi Nissim Abrin • Rabbi David Bigman • Mrs. Dina Blank<br />

Rabbi Jesse Horn • Rabbi Shaya Karlinsky • Rabbi Moshe Lichtman<br />

Rabbi Chaim Pollock • Rabbi Azriel Rosner • Rabbi Ari Shvat<br />

1<br />

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • The Benjamin and Rose Berger CJF Torah To-Go Series • Pesach 5776

We thank the following synagogues who have pledged to be<br />

Pillars of the Torah To-Go® project<br />

Congregation Ahavas<br />

Achim<br />

Highland Park, NJ<br />

Congregation Ahavath<br />

Torah<br />

Englewood, NJ<br />

Congregation Beth<br />

Shalom<br />

Rochester, NY<br />

Congregation<br />

Shaarei Tefillah<br />

Newton Centre, MA<br />

The Jewish Center<br />

New York, NY<br />

Young Israel of Beth El in<br />

Boro Park<br />

Brooklyn, NY<br />

Young Israel of<br />

Century City<br />

Los Angeles, CA<br />

Young Israel of<br />

New Hyde Park<br />

New Hyde Park, NY<br />

Young Israel of<br />

West Hempstead<br />

West Hempstead, NY<br />

Richard M. Joel, President and Bravmann Family University Professor, Yeshiva University<br />

Rabbi Kenneth Brander, Vice President for University and Community Life, Yeshiva University<br />

Rabbi Yaakov Glasser, David Mitzner Dean, Center for the Jewish Future<br />

Rabbi Menachem Penner, Max and Marion Grill Dean, Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary<br />

Rabbi Robert Shur, Series Editor<br />

Rabbi Joshua Flug, General Editor<br />

Rabbi Michael Dubitsky, Editor<br />

Andrea Kahn, Copy Editor<br />

Copyright © 2016 All rights reserved by Yeshiva University<br />

Yeshiva University Center for the Jewish Future<br />

500 West 185th Street, Suite 419, New York, NY 10033 • office@yutorah.org • 212.960.0074<br />

This publication contains words of Torah. Please treat it with appropriate respect.<br />

For sponsorship opportunities, please contact Paul Glasser at 212.960.5852 or paul.glasser@yu.edu.<br />

2<br />

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • The Benjamin and Rose Berger CJF Torah To-Go Series • Pesach 5776

Table of Contents<br />

Pesach—Yom Haatzmaut 2016/5776<br />

Dedicated in memory of Cantor Jerome L. Simons<br />

The Seder of the Seder<br />

Rabbi Benjamin Blech . . . . . .. . ..................................................................... Page 5<br />

Defining Mesorah<br />

Rabbi Reuven Brand . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ................................................................... Page 8<br />

In Time, Out of Time, or Beyond Time? Women and Sefiras HaOmer<br />

Rabbi Daniel Z. Feldman . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ......................................................... Page 13<br />

The Giving Jew: Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik on Yachatz and Hachnasat<br />

Orchim<br />

Rabbi Aaron Goldscheider . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ................................................................. Page 17<br />

Understanding an Unfriendly Minhag: Not Eating Out on Pesach<br />

Rabbi Yona Reiss . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ............................................................................ Page 21<br />

Freedom To…Not Freedom From: Pesach and the Road to Redemption<br />

Mrs. Shoshana Schechter . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ................................................................. Page 26<br />

When Iyov Left Egypt<br />

Rabbi Mordechai Torczyner . . . . . . . . . . . . ................................................................. Page 30<br />

How do We Transmit Emunah? Maximizing the Pesach Seder<br />

Ilana Turetsky, Ed.D. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ................................................................. Page 33<br />

The Original Birthright: Seder Night in Jerusalem<br />

Rabbi Daniel Yolkut . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ................................................................. Page 37<br />

Insights to the Pesach Seder<br />

From the Rabbinic Alumni Committee of the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary . . . . . . . Page 39<br />

Yom Haatzmaut: An Introduction<br />

Mrs. Stephanie Strauss . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ................................................................. Page 45<br />

Eretz Yisroel: The Prism of God<br />

Rabbi Nissim Abrin . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ................................................................. Page 48<br />

The Meaning of the Establishment of the State of Israel<br />

Rabbi David Bigman . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ................................................................. Page 50<br />

3<br />

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • The Benjamin and Rose Berger CJF Torah To-Go Series • Pesach 5776

Yom Ha’atzmaut: Heeding the Call<br />

Mrs. Dina Blank . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ................................................................. Page 52<br />

Eretz Yisrael and the First 61 Chapters of the Torah<br />

Rabbi Jesse Horn . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ................................................................. Page 54<br />

Kedushat Eretz Yisrael<br />

Rabbi Shaya Karlinsky . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ................................................................. Page 56<br />

Simchah Shel Mitzvah<br />

Rabbi Moshe Lichtman . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ................................................................. Page 58<br />

A Torah Approach to Medinat Yisrael<br />

Rabbi Chaim Pollock . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ................................................................. Page 60<br />

Three Days before Aliyah<br />

Rabbi Azriel Rosner . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ................................................................. Page 62<br />

What’s So Important About Eretz Yisrael?!<br />

Rabbi Ari Shvat . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ................................................................. Page 64<br />

4<br />

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • The Benjamin and Rose Berger CJF Torah To-Go Series • Pesach 5776

Introduction<br />

For some families, it is the odors<br />

of charred metal mixing with<br />

the fresh scents of new plastic<br />

counter coverings. For others, it is<br />

the neatly piled clothing next to the<br />

suitcases being filled to capacity. But<br />

for all, the hullabaloo of the night<br />

preceding the Pesach seder is broken<br />

by the family gathering to fulfill the<br />

mitzvah of bedikas chametz. Searching<br />

for chametz is a process that begins<br />

long before we begin negotiating<br />

who will hold the candle, feather,<br />

spoon, and bag for our formal bedikas<br />

chametz. Our homes are essentially<br />

chametz-free when we commence this<br />

sacred obligation, and the chametz<br />

not located can be rendered ownerless<br />

by the process of bitul (nullification).<br />

Moreover, our custom (see Rama,<br />

OC 432:2) is to distribute 10 pieces<br />

of bread throughout the house in<br />

order to ensure that the effort results<br />

in some form of productive outcome.<br />

How are we to understand this<br />

entire experience? On the one hand,<br />

searching for chametz is one of the<br />

most central elements of preparing<br />

for Pesach, yet the mitzvah of bedikas<br />

chametz — as is practiced today in<br />

homes that are already free of chametz<br />

— seems to be a manufactured ritual<br />

that is devoid of any true purpose,<br />

with an artificial outcome.<br />

The answer is that Pesach is about<br />

more than just celebrating the<br />

redemption of the Jewish people.<br />

Recalling the narrative of our Exodus<br />

from Egypt is an obligation that is<br />

incumbent upon us every single<br />

day. The distinguishing dynamic<br />

of the Pesach seder is that we care<br />

about more than just the outcome<br />

of redemption — we care about the<br />

process that anticipates it as well. On<br />

the seder night, we are obligated to<br />

evoke the curiosity of our children<br />

and each other. Beyond providing<br />

essays and answers that depict<br />

the miraculous journey of yetzias<br />

Mitzrayim, we are also seeking to<br />

inspire the Jewish people to aspire and<br />

reach for the world of redemption as<br />

well. Indeed, to question and to search<br />

is part of the journey of redemption<br />

as well. We engage in many rituals<br />

that solicit the questioning of the next<br />

generation because redemption must<br />

be built upon a foundation of desire<br />

and aspiration.<br />

We may all be aware that the search for chametz<br />

will likely produce very limited unanticipated<br />

results. Yet there is inherent and deep value to<br />

the experience of “searching” in general.<br />

Rabbi Yaakov Glasser<br />

David Mitzner Dean, YU Center for the Jewish Future<br />

Rabbi, Young Israel of Passaic-Clifton<br />

We may all be aware that the search<br />

for chametz will likely produce very<br />

limited unanticipated results. Yet<br />

there is inherent and deep value to the<br />

experience of “searching” in general.<br />

As we walk through our homes,<br />

and through our lives, we begin to<br />

appreciate where the exile has taken<br />

hold, and left our lives incomplete,<br />

where our “questions” have been left<br />

unanswered by G-d’s hidden presence,<br />

and how redemption would bring<br />

seder, order, to our personal, familial,<br />

and national lives.<br />

We are living in a generation of deep<br />

confusion. On the one hand, our<br />

home is so well prepared for Pesach,<br />

our world so primed for redemption.<br />

We enjoy countless synagogues,<br />

schools, outreach organizations, and<br />

a homeland to which we can return.<br />

On the other hand, redemption seems<br />

so elusive as uncertainty and terror<br />

grip so many nations, including our<br />

precious State of Israel. It is our role<br />

to continue to aspire, to continue to<br />

question, to continue to search, until<br />

we discover the ultimate redemption<br />

and can once again celebrate Pesach<br />

together in Yerushalayim Ir Hakodesh.<br />

5<br />

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • The Benjamin and Rose Berger CJF Torah To-Go Series • Pesach 5776

The Seder of the Seder<br />

The word seder means order —<br />

and yet the order of the seder<br />

seems very strange.<br />

The ritual of Passover night is divided<br />

into three distinct parts. The first is<br />

comprised of all the readings from the<br />

Haggadah until the section known<br />

as shulchan orech, the prepared table.<br />

At this point we pause to eat our<br />

festive meal. Then we return to the<br />

text to conclude the readings and final<br />

portions of the holiday text.<br />

Simply put, it is pray, eat, and pray<br />

again.<br />

Somehow that begs for an<br />

explanation. With regard to our<br />

morning prayers, Jewish law is quite<br />

clear. We must first take care of our<br />

spiritual obligations to God before we<br />

are permitted to satisfy our physical<br />

wants. We have to complete our<br />

prayers before we are allowed to sit<br />

down for our morning meal.<br />

Yet at the seder, Jewish law seems<br />

unable to make up its mind about<br />

proper priorities. Yes, prayers to God<br />

do come first. We spend considerable<br />

time until we get to our food. But in<br />

what would appear to be “the middle<br />

of the book,” we halt our God-talk to<br />

placate our hunger. We recline and<br />

leisurely eat until we are satiated and<br />

then our slowly closing eyes are pulled<br />

back open to conclude the closing<br />

unit of the Haggadah.<br />

Is this simply a concession to human<br />

frailty, an acknowledgment that it<br />

would be too difficult to continue<br />

reading from a text without some<br />

sustenance? Is the placement of<br />

the meal in the middle no more<br />

meaningful than an intermission made<br />

necessary by a Rabbinic recognition<br />

that people couldn’t be expected to<br />

pray for so long a time without a break<br />

for nourishment?<br />

Or is there in fact some greater<br />

meaning, some profound order, to the<br />

seder of the seder?<br />

The answer becomes clear when we<br />

take note of the exact placement<br />

of the meal in the context of<br />

the entire Haggadah. Hallel is a<br />

magnificent selection of Psalms that<br />

are customarily recited on holidays.<br />

It consists of a number of chapters<br />

that together form a self-contained<br />

unit. When recited in the synagogue,<br />

the Hallel begins with a blessing<br />

and closes with a blessing — a clear<br />

indication that it is meant to be<br />

uninterrupted, an organic whole with<br />

a clearly defined structure.<br />

How remarkable then that at the<br />

seder, we read but the first two<br />

chapters of Hallel, chapters 113 and<br />

114 of the Book of Psalms, and then<br />

move on to the meal only to return to<br />

the concluding portion, chapters 115-<br />

118, after we have eaten our fill.<br />

Our original question becomes even<br />

stronger. If we feel that it is only<br />

right, just as with our daily morning<br />

practice, to fulfill the spiritual<br />

Rabbi Benjamin Blech<br />

Faculty, IBC Jewish Studies Program,<br />

Yeshiva University<br />

obligation of praise to God before<br />

tending to our physical needs and<br />

we therefore recite the beginning of<br />

Hallel, why not at the very least finish<br />

it? Would it really be so hard to delay<br />

eating for just a little bit longer? And<br />

if indeed a complete Hallel is out of<br />

place because of its length and the<br />

rabbis felt that the seder participants<br />

were entitled at long last to start the<br />

meal, couldn’t they have deferred<br />

the first two paragraphs to the aftermeal<br />

location accorded to the major<br />

portion of the prayer?<br />

Surely the exact place where we make<br />

the break in Hallel has a great deal of<br />

significance. And once we identify<br />

the thematic difference between the<br />

first two chapters of Hallel and the<br />

remainder, we will have the key to<br />

understanding the reason for the<br />

remarkable sequence we’ve identified<br />

as pray-eat-pray.<br />

The seder consists of three main units<br />

because it is on Passover night that we<br />

as a people first came to accept and<br />

understand God.<br />

The English word God is a contraction<br />

of good. It conveys only one aspect of<br />

His being: His goodness. In Hebrew,<br />

the four letter name of God, the<br />

Tetragrammaton, is a combination<br />

of three words that express the three<br />

6<br />

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • The Benjamin and Rose Berger CJF Torah To-Go Series • Pesach 5776

categories of time: Hoyah means was;<br />

Hoveh means is; Yihyeh means will be.<br />

These three words combined together<br />

are the most powerful way we refer<br />

to the Almighty. By using this name,<br />

we acknowledge God’s presence for<br />

all time. God was in the past, the allpowerful<br />

Creator of the world Who<br />

revealed Himself to our ancestors. He<br />

is in the present as the ongoing source<br />

of all of our daily blessings. And He<br />

will continue to be in the future,<br />

fulfilling all the promises He made as<br />

part of our covenantal relationship.<br />

To believe in a God who is limited<br />

to a presence that fails to encompass<br />

all three aspects of time is to make<br />

a mockery of His greatness. And<br />

so every year on the first night of<br />

Passover we conduct a seder divided<br />

into three acts:<br />

• The first is devoted to explaining the<br />

role of God in the past.<br />

• The second emphasizes His<br />

closeness to us in the present.<br />

• The last stresses our firm belief that<br />

just as He redeemed us long ago from<br />

the slavery of Egypt, He will finally<br />

bring about the promised messianic<br />

redemption in the future.<br />

Look carefully at the prayers and the<br />

rituals before the meal and you will<br />

see that their intent is to elaborate on<br />

God’s role in the past. The response to<br />

the young children’s four questions,<br />

the Mah Nishtanah, about the<br />

meaning of this night, begins with<br />

the paragraph that recounts how<br />

“we were slaves to Pharaoh in Egypt<br />

and the Lord our God took us out<br />

from there with a strong hand and an<br />

outstretched arm.” We go back to the<br />

time when our ancestors at first were<br />

idolaters and then the Lord drew us<br />

near to His service. We talk about<br />

Laban, the wandering Aramean, and<br />

how we ended up in Egypt. We recite<br />

the 10 plagues and, with Dayenu,<br />

express our gratitude for all the things<br />

that God did for us, each one of which<br />

alone would have warranted gratitude.<br />

That, we then sum up, is why we have<br />

the Paschal lamb, the matzoh, and the<br />

bitter herbs.<br />

And that is why we then recite only<br />

the two chapters from the Book<br />

What’s on the<br />

Seder Plate?<br />

Although the history of the Seder goes back<br />

thousands of years, each item on the Seder<br />

Plate still has deep significance to our<br />

personal lives today.<br />

EGG<br />

Reminds us to mourn that we can no<br />

longer offer the Korban Chagigah<br />

(Holiday sacrifice) since we no longer have<br />

the Temple. An egg is a sign of mourning<br />

because it is round, symbolizing the cycle<br />

of life from birth to death.<br />

We yearn for God to redeem us<br />

from our present exile so<br />

that we will be able to serve<br />

God in the most optimal way.<br />

LETTUCE<br />

A form of Marror.<br />

Lettuce is not<br />

always bitter, but it<br />

can become hard<br />

and bitter if left in the<br />

ground for too long<br />

before being harvested.<br />

This hardening process<br />

parallels the transformation<br />

in attitude that the Egyptians<br />

had toward the Jews: Just as<br />

lettuce starts out soft and ends up<br />

hard and bitter, so too, the Egyptians<br />

originally welcomed Jacob and the Jewish<br />

people to Egypt with open arms, but later turned<br />

their backs on the Jewish people and subjected<br />

them to backbreaking labor.<br />

The lettuce reminds us to remain loyal<br />

and appreciative toward the people who<br />

help us. We should not be like the<br />

Egyptians and the lettuce, which are soft<br />

at first but later become hard and bitter.<br />

of Psalms out of the larger prayer<br />

commonly recited as Hallel, chapters<br />

113 and 114.<br />

These chapters share this emphasis<br />

on praise for past kindnesses. We<br />

who were once slaves to Pharaoh<br />

are now servants of the Lord (Psalm<br />

113). God intervened on our behalf<br />

with great miracles, with the splitting<br />

of the sea and the trembling of the<br />

ROASTED BONE<br />

Reminds us of the Korban Pesach (Paschal Lamb) that was eaten at the<br />

seder in the times of the Temple. Since we no longer have our Temple, we<br />

can’t offer the Korban Pesach any more, and we don’t eat this meat, either.<br />

The Korban Pesach was roasted because roasted meat is considered<br />

something eaten only by royals; poor people are more likely to just boil<br />

their meat. The Korban Pesach reminds us to celebrate that God elevated<br />

us from a nation of slaves to a holy nation of royalty. We are not<br />

just regular people, we are children of the King!<br />

HORSERADISH<br />

Reminds us of the bitter<br />

enslavement of our forefathers in<br />

Egypt. Many people eat LETTUCE<br />

(see above) for Marror instead of<br />

horseradish.<br />

CHAROSET<br />

A mixture of apples, cinnamon,<br />

nuts, and wine. Its<br />

appearance reminds us of<br />

the bricks and mortar<br />

the Jews used in Egypt.<br />

We dip the bitter Marror<br />

into the Charoset to<br />

sweeten the bitterness of<br />

the Marror. This is a<br />

reminder that we can<br />

always find a spark of<br />

goodness and something<br />

to appreciate within every<br />

challenge we face in life.<br />

Every dark cloud has a silver<br />

lining.<br />

KARPAS<br />

A vegetable like celery or a potato. We<br />

dip the Karpas into saltwater to remind<br />

us of the salty tears the Jews shed from<br />

the backbreaking labor in Egypt.<br />

When God saw the Jews’ tears and heard<br />

their cries, God‘s mercy was aroused<br />

and He brought the Jews out of Egypt.<br />

The salty tears therefore remind us of<br />

God’s tremendous mercy, and<br />

the power of prayer to<br />

save us from even the<br />

most difficult of<br />

circumstances.<br />

We dip the Karpas<br />

into saltwater<br />

Infographic by Rachel First, Educational Designer for NCSY Education.<br />

For more educational infographics and materials from NCSY, please visit: education.ncsy.org<br />

7<br />

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • The Benjamin and Rose Berger CJF Torah To-Go Series • Pesach 5776

mountains (Psalm 114). We go no<br />

further at this point because we<br />

have not yet shifted our attention<br />

to the second major way in which<br />

we understand God’s role in time as<br />

expressed by His very name — Hoveh<br />

— He Is.<br />

An anonymous author put it very well<br />

when he said, “The past is history. The<br />

future is mystery. The here and now<br />

is a precious gift from God — and<br />

that’s why we call it the present.” We<br />

could not survive even for a moment<br />

without God’s providential care. The<br />

most powerful way in which this<br />

is expressed is by way of our daily<br />

bread. Manna may no longer descend<br />

from heaven as it miraculously did<br />

for our ancestors in the desert, but<br />

we are spiritually sensitive enough to<br />

recognize that without the Almighty,<br />

we wouldn’t be blessed with the most<br />

basic requirements for our continued<br />

existence. To eat our food is to know<br />

God in the present. Shulchan orech,<br />

the section of the seder in which we<br />

partake of our meal, is to absorb in<br />

both a literal and metaphorical way<br />

the reality of God’s nearness. He feeds<br />

us — so we know that He loves us.<br />

The meal portion of the seder is not<br />

an intermission. It is another moment<br />

of awareness, different and elevated.<br />

It moves us from the Hoyah to the<br />

Hoveh. It makes the concept of the<br />

God of the past developed in the<br />

first section much more meaningful,<br />

something that is relevant for us<br />

today. In this second section, the God<br />

of the present is personal. We sit at<br />

His table and we know that just like<br />

a concerned parent, God nudges us,<br />

“Eat my child, eat.”<br />

We express all of this every time we<br />

recite the Grace After Meals:<br />

ברוך אתה ה’, א-לוקינו מלך העולם, הזן את<br />

העולם כולו בטובו, בחן בחסד וברחמים, הוא<br />

נותן לחם לכל בשר, כי לעולם חסדו ... כי הוא<br />

א-ל זן ומפרנס לכל ומטיב לכל, ומכין מזון<br />

לכל בריותיו אשר ברא.<br />

Blessed are you, Hashem (the one whose<br />

name includes a relationship with us<br />

in the present) our God, King of the<br />

universe, who nourishes (present tense)<br />

the entire world in his goodness, with<br />

grace, with kindness, and with mercy.<br />

He provides (present tense) food to all<br />

flesh, for his kindness is eternal ... He<br />

is God who nourishes (present tense)<br />

and sustains (present tense) all, and He<br />

prepares (present tense) food for all of<br />

His creatures which He has created.<br />

The seder has brought us from the<br />

past to the present. But it is still not<br />

enough. The seder still cannot be<br />

over. We need to move on to the final<br />

and most complete understanding<br />

of God’s relationship with us. After<br />

the meal we at last turn to tzofun, the<br />

Hebrew word for hidden. It represents<br />

the matzoh we set aside at the<br />

beginning of the meal to be “saved for<br />

later.” It is not the matzoh of the past<br />

but the matzoh of the future. It is not<br />

the matzoh of memory that recalls the<br />

Exodus from Egypt. It is the matzoh<br />

of hope for a not as yet fulfilled<br />

redemption from the bitterness of the<br />

exile and the diaspora. It is the matzoh<br />

that was wrapped up for the children<br />

in the firm belief that they will enjoy<br />

a long awaited future of messianic joy.<br />

Tzofun serves as a bridge to the third<br />

part of the seder when we move from<br />

gratitude for what is to even greater<br />

anticipation of what will be.<br />

It is the third part of the seder that<br />

captures the real significance of the<br />

Passover festival. This is not meant to<br />

be a holiday designated primarily as<br />

a trip down memory lane, a nostalgic<br />

reminder of an ancient story that<br />

has no realistic relevance to us. The<br />

conclusion of the seder comes to<br />

affirm that what happened before<br />

will happen again. The first ge’ulah<br />

(redemption) was but a preview<br />

of coming attractions. There will<br />

assuredly be a ge’ulah sh’lemah — a<br />

final and complete redemption.<br />

And so we open the door for Elijah,<br />

the prophet Jewish tradition identifies<br />

as the one who comes to announce<br />

the arrival of the Messiah. Better yet,<br />

we ask our children to perform this<br />

task. After all, it is a ritual that relates<br />

to the future and it is the young who<br />

will most benefit from its fulfillment.<br />

We ask God to pour forth his wrath<br />

upon the nations who so viciously<br />

abused us. We recite those passages<br />

of Hallel rooted in our hopes for the<br />

future that we did not yet say in the<br />

first section of the seder concentrating<br />

on the past. We pray for the return to<br />

Jerusalem, not just the city but the<br />

rebuilt city, the city of King David’s<br />

dreams and King Solomon’s Temple.<br />

We close with the nirtzah, in which<br />

we express the hope that soon and<br />

speedily God “will redeem us to Zion<br />

with glad song,” and Passover will at<br />

last fulfill its full promise.<br />

Pray, eat, and then pray again. The<br />

seder captures the three tenses of<br />

God’s name. It incorporates all of<br />

time. And that is what makes the seder<br />

timeless.<br />

8<br />

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • The Benjamin and Rose Berger CJF Torah To-Go Series • Pesach 5776

Defining Mesorah<br />

Every year, on the night of<br />

Pesach, Jewish people around<br />

the world convene at their<br />

seder tables and collectively, we share<br />

our story with the next generation.<br />

This transmission of our heritage, its<br />

laws and values, ensures the continuity<br />

of our Jewish community and creates<br />

a bond of tradition we call mesorah —<br />

tradition. The full import and meaning<br />

of this Hebrew term is lacking<br />

somewhat in the English translation.<br />

Beyond “tradition,” the overarching<br />

character of mesorah connotes a<br />

connection to a narrative, movement,<br />

and mission that transcends<br />

generational boundaries. Mesorah is<br />

expressed in the transmission of living<br />

teachings, character, and profiles of a<br />

Torah community, and is an essential<br />

component of Judaism. Hence, while<br />

mesorah has seventy faces, its basic<br />

and universal qualities transcend all<br />

boundaries and unite all segments of<br />

the Torah community.<br />

Yet over the generations we struggle<br />

with the question: how do we define<br />

our mesorah? What are its features<br />

and parameters? Which practices fit<br />

within its broad parameters and how<br />

do we apply it in every generation?<br />

Surely, there are notable differences<br />

between various specific practices at<br />

the seder that vary from community<br />

to community and from time to time,<br />

so how are we to determine what<br />

developments fall within our mesorah?<br />

It is fascinating that the Hagadah can<br />

be a helpful guide in addressing these<br />

issues. The Hagadah is not only a<br />

traditional text — it is a paradigmatic<br />

text of tradition including elements<br />

that, as we study it, give us insight<br />

into the nature, character and key<br />

components of mesorah. Although<br />

these reflections are not ironclad<br />

proofs to a full definition of mesorah,<br />

we can still gain insight into this crucial<br />

concept. 1 With the Hagadah as our<br />

guide, we can learn timeless lessons.<br />

The concept of mesorah, which<br />

reflects and represents continuity of<br />

generations, is primarily focused on<br />

the Oral tradition. The Written Torah<br />

— the Tanach — is the backbone of<br />

our relationship with Hashem, while<br />

the Oral Torah provides spirit, depth,<br />

context, and meaning. At Sinai, Hashem<br />

instructed that we interpret the Written<br />

Torah through the Oral Torah, to guide<br />

how our Jewish lives take shape and<br />

form. It is this oral transmission that is<br />

the shared covenantal bond between us<br />

and Hashem. 2<br />

Our Hagadah dedicates its largest<br />

section — Tzei Ul’mad — to the<br />

midrashic interpretation of the story<br />

of yetziat Mitzrayim. It is because<br />

this is the primary expression of<br />

mesorah — the Oral tradition and<br />

its transmission of the methodology<br />

Rabbi Reuven Brand<br />

Rosh Kollel, YU Torah Mitzion Kollel of Chicago<br />

and understanding of Torah analysis<br />

from teacher to student and parent to<br />

child in each generation. The Hagadah<br />

is teaching that our mesorah and our<br />

collective story is built on the internal<br />

logic of the halachic system taught<br />

to us by our sages, expressed in this<br />

selection of midrash.<br />

Perhaps this is also the reason why the<br />

selection in Devarim was chosen as the<br />

Biblical text for discussion at the seder.<br />

As opposed to verses in Shemot, these<br />

four verses in Devarim lend themselves<br />

to deep midrashic explication, while<br />

the narrative in Shemot is understood<br />

on its primary, pshat level.<br />

We can also understand why the seder<br />

includes many Rabbinic mitzvot. The<br />

Rambam, in the introduction to his<br />

commentary on the Mishna, explains<br />

that our Torah Sheba’al Peh includes<br />

both the exegetical interpretations<br />

of Torah, which are binding on a<br />

Biblical level, and the Rabbinic<br />

aspects of Jewish life including<br />

Rabbinic mitzvot, enactments, and<br />

restrictions. Hence our seder includes<br />

many Rabbinic requirements that play<br />

a prominent role, such as drinking<br />

four cups and leaning in a luxurious<br />

manner, which express this dimension<br />

of our mesorah of Torah Sheba’al Peh.<br />

Many thanks to Mrs. Ora Lee Kanner, Rabbi Dr. Leonard Matanky, Professor Leslie Newman<br />

and Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. Schacter for their assistance with this article.<br />

9<br />

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • The Benjamin and Rose Berger CJF Torah To-Go Series • Pesach 5776

However, it is not only the legal,<br />

learning aspects of Torah that<br />

comprise mesorah. There is a second,<br />

core aspect of mesorah. It transmits the<br />

behaviors and practices of generations<br />

over time, reflecting the contours<br />

of the Torah community. Rabbi<br />

Joseph B. Soloveitchik developed this<br />

notion at length in a Yahrzeit shiur in<br />

memory of his father:<br />

שתי מסורות ישנן: א( מסורה אחת המתיחסת<br />

כולה למסורה של לימוד, ויכוח, משא ומתן<br />

והוראה שכלית, זה אומר כך וזה אומר כך, זה<br />

נותן טעם לדבריו וזה נותן טעם לדבריו, ועומדין<br />

למנין, כמו שהתורה מציירת לנו בפרשת זקן<br />

ממרא. ב( מסורת מעשית של הנהגת כלל<br />

ישראל בקיום מצוות וזו מיסדת על הפסוק<br />

"שאל אביך ויגדך זקניך ויאמרו לך."<br />

שיעורים לזכר אבא מרי ז"ל חלק א' עמ' רמ"ט<br />

There are two types of mesorah: 1) One<br />

type of mesorah that wholly relates to<br />

learning: the debate, the exchange and<br />

the logical instruction; one says this and<br />

one says that; one provides his reasoning<br />

and the other provides his reasoning<br />

and they come to a consensus as the<br />

Torah describes in the section about the<br />

rebellious elder. 2) There is a mesorah<br />

based on the [actual] practices of the<br />

Jewish people and this is based on the<br />

verse “Ask your father and he will relate it<br />

to you, the elders and they will tell you.”<br />

Shiurim L’Zecher Abba Mari z”l<br />

Vol. I pg. 249<br />

Therefore, our seder includes not only<br />

paragraphs of limud and Rabbinic<br />

requirements derived through limud, it<br />

also shares a vision of the way a seder<br />

should take shape. These traditions<br />

of mesorah include various minhagim<br />

— customs. Some customs are the<br />

mesorah of a particular community<br />

that develop over time, such as which<br />

specific vegetables to use for dipping<br />

and how to arrange the seder plate.<br />

Other traditions are universal and<br />

remain unmoved. One example is the<br />

practice of leaning as an expression<br />

of freedom. The overwhelming<br />

tradition is to maintain our fealty to<br />

the Talmudic practice of reclining<br />

even though its rationale is no longer<br />

operative today. 3<br />

The Hagadah also teaches by example<br />

that the sages of the generation — the<br />

chachmei hamesorah, in the words<br />

of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik,<br />

are crucial to defining mesorah. In<br />

his brief introduction to the Mishne<br />

Torah, the Rambam enumerates the<br />

names of forty sages who transmitted<br />

the tradition from Moshe at Sinai to<br />

Rav Ashi at the close of the Talmud.<br />

This list is not merely a historical<br />

record; it serves to identify the<br />

stewards of the mesorah over the<br />

generations. Mesorah is not only<br />

transmitted by communal practice —<br />

it is shepherded and defined by the<br />

Rabbinic stewards of each generation.<br />

Rabbi Soloveitchik discussed this idea<br />

in a talk he delivered on June 19, 1975<br />

to the RIETS Rabbinic alumni: 4<br />

The truth in talmud Torah can<br />

be achieved through singular<br />

halachic Torah thinking, and Torah<br />

understanding. The truth is attained<br />

from within, in accord with the<br />

methodology given to Moses and passed<br />

on from generation to generation. The<br />

truth can be discovered only through<br />

joining the ranks of the chachmei<br />

hamesorah.<br />

This idea was expressed by Rabbi<br />

There are two types<br />

of mesorah, one that<br />

wholly relates to<br />

learning: the debate, the<br />

exchange and the logical<br />

instruction and there is<br />

a mesorah based on the<br />

[actual] practices of the<br />

Jewish people.<br />

10<br />

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • The Benjamin and Rose Berger CJF Torah To-Go Series • Pesach 5776

Soloveitchik more than thirty years<br />

earlier based on conversations and<br />

teachings that he received from his<br />

own father: 5<br />

פעמים רבות הרצתי לפני אבא מרי הגאון<br />

החסיד, זצ”ל, והוא שבח את הדברים מאד<br />

וגם חזר עליהם בשיעוריו, כי מדברי הרמב”ם<br />

מוכח, שמסורה מהוה חלות שם בפ”ע בנוגע<br />

לתורה שבע”פ, ואינה רק דין נאמנות וברור.<br />

ונראה, דבעיקר של אמתת תורה שבע”פ<br />

נאמרו שתי הלכות מיוחדות: א( דחכמי<br />

המסורה ממשה ואילך נאמנים למסר את<br />

התורה שקבלו מסיני, ותורה שבע”פ, המצויה<br />

עכשיו בידינו, היא, היא, אותה התורה,<br />

שנתנה למשה מפי הגבורה; ב( דעצם הקבלה<br />

אינה רק מעשה בירור בעלמא, אלא מהוה<br />

חלות שם בפ”ע של מסורה וקבלה, דתורה<br />

שבע”פ נתנת להמסר כמו תורה שבכתב,<br />

שנתנה להכתב, ועצמה של תורה שבע”פ<br />

נתפס במסורה כמו זו שבכתב — בכתיבה.<br />

Many times I presented this idea to my<br />

father, the pious scholar, zt”l, and he<br />

greatly praised this idea and presented it<br />

in his lectures — that from the language of<br />

Rambam, it is clear that the mesorah has<br />

its own unique status when it comes to the<br />

Oral Tradition. It is not merely a means<br />

of verifying the information. It seems<br />

that there are two distinct laws regarding<br />

the verification of the Oral Tradition. 1)<br />

The scholars of the mesorah from Moshe<br />

Rabbeinu and on are the authorities to<br />

transmit the Torah that was received from<br />

Sinai and the Oral Tradition that is now<br />

in our hands is the same Torah that was<br />

given to Moshe by the Almighty. 2) The<br />

actual transmission is not just a means<br />

of verification but has an independent<br />

status of mesorah. The Oral Tradition<br />

was intended to be transmitted the same<br />

way that the Written Torah was intended<br />

to be written. The actual Oral Tradition<br />

achieves its status through mesorah just<br />

as the Written Torah achieves its status<br />

through writing it.<br />

We now appreciate why our Hagadah<br />

introduces the story of the Exodus<br />

with the story of five Tanaim (rabbis<br />

of the Mishna) in Bnei Brak, who<br />

discussed yetziat Mitzrayim all night.<br />

We open our seder with this anecdote<br />

not just to show the extent to which<br />

we should aspire to perform this great<br />

mitzvah, but also to frame it in the<br />

context of our chachmei hamesorah.<br />

We recognize that there are great<br />

sages, people who devote themselves<br />

so fully to Torah that their study<br />

would continue unabated had they not<br />

been interrupted by their students,<br />

to whom we look for direction when<br />

shaping our story of vehigad’ta levincha<br />

— you shall tell your children.<br />

This story also alludes to the<br />

community’s role in guiding the<br />

mesorah. While the Rabbinic<br />

luminaries of each generation are<br />

the arbiters of mesorah, they do so<br />

with sensitivity to and in concert<br />

with the community. Hence it was<br />

the students, the populace, who<br />

reminded the sages that it was time<br />

for Shacharit, and the Bnei Brak seder<br />

then ended. The Rabbis’ students,<br />

who comprise and are immersed in<br />

the general population, reflect the<br />

realities and needs of the people<br />

of that time so that the sages can<br />

lead in a way that meets the needs<br />

of the specific time and place. 6 In<br />

addition, the students’ presence<br />

was also important to establish a<br />

communal precedent that sippur<br />

yetziat Mitzrayim may be fulfilled all<br />

night, in accordance with the view of<br />

Rabbi Akiva. It is up to the chachmei<br />

hamesorah to determine normative<br />

practice, and it is the community<br />

that carries the responsibility to<br />

maintain the mesorah and continue<br />

its practice. It is precisely due to this<br />

fealty, that the chachmei hamesorah<br />

give significant weight to the practices<br />

of the community as they reflect<br />

the mesorah. 7 Therefore, even Hillel<br />

the elder, when faced with a Pesachrelated<br />

question about which he was<br />

unsure, instructed his questioners to<br />

inquire how people practice to clarify<br />

what the ruling should be:<br />

אמר להן הלכה זו שמעתי ושכחתי אלא הנח<br />

להן לישראל אם אין נביאים הן בני נביאים<br />

הן למחר מי שפסחו טלה תוחבו בצמרו מי<br />

שפסחו גדי תוחבו בין קרניו ראה מעשה ונזכר<br />

הלכה ואמר כך מקובלני מפי שמעיה ואבטליון.<br />

פסחים סו.<br />

“I have heard this law,” he answered,<br />

“but have forgotten it. But leave it to<br />

Israel: if they are not prophets, yet they<br />

are the children of prophets!” On the<br />

morrow, he whose Passover was a lamb<br />

stuck it [the knife] in its wool; he whose<br />

Passover was a goat stuck it between<br />

its horns. He saw the incident and<br />

recollected the halachah and said, “Thus<br />

have I received the tradition from the<br />

mouth[s] of Shemaiah and Abtalyon.”<br />

Pesachim 66a (Soncino<br />

Translation)<br />

We learn an additional lesson from<br />

the next section of the Hagadah:<br />

that an individual rabbi alone does<br />

not establish mesorah. The Hagadah<br />

relates that although Rabbi Elazar<br />

ben Azaryah viewed himself as a<br />

sage of seventy, he did not merit to<br />

teach the obligation of reciting yetziat<br />

Mitzrayim at night until Ben Zoma<br />

taught it. Rabbi Elazar ben Azarya was<br />

convinced of his view in the halacha<br />

and knew he was a great scholar. Yet<br />

it wasn’t until his idea was recognized<br />

and accepted by the great Rabbinic<br />

authority of the generation (Ben<br />

Zoma was the senior Darshan, see<br />

Sotah 15) that it became normative<br />

mesorah. 8 When a question regarding<br />

a significant change in practice or<br />

approach in mesorah is raised, only a<br />

Rabbinic luminary, who is recognized<br />

by the Torah community as a giant<br />

of the generation, can establish a<br />

precedent for the mesorah. It is then<br />

that the practice becomes an accepted<br />

mesorah by the community.<br />

11<br />

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • The Benjamin and Rose Berger CJF Torah To-Go Series • Pesach 5776

Simultaneously, the great sages of<br />

the generation do not shape the<br />

contours of mesorah through the<br />

exercise of power or authority, rather<br />

though the weight and merit of their<br />

views. Perhaps this is why Rabban<br />

Gamliel, who was the most senior<br />

Rabbinic personality during the<br />

Yavneh period, is noticeably absent<br />

from the aforementioned seder of the<br />

five sages; according to the Tosefta,<br />

he was celebrating the seder in Lod.<br />

The seder scene we describe likely<br />

occurred while Rabban Gamliel was<br />

removed from his role as Nasi of<br />

the Beit Din due to his overly harsh<br />

imposition of authority over his<br />

disciple, Rabbi Yehoshua. The Gemara<br />

(Berachot 27) relates that the Rabbinic<br />

community removed Rabban Gamliel<br />

from his post and replaced him with<br />

Rabbi Elazar ben Azarya. For this<br />

reason, Rabbi Elazar ben Azarya is<br />

seated at the head of the table in Bnei<br />

Brak, in the center of the Rabbis. 9 We<br />

learn that no matter how great a sage<br />

one may be, the halacha and mesorah<br />

cannot be determined by force, only<br />

by consensus of sages. 10<br />

In closing, we can readily understand<br />

why mesorah plays such a central role<br />

in the seder and the Hagadah, since<br />

its focus — the mitzvah of sippur<br />

yetziat Mitzrayim— is primarily an<br />

educational one. Ideally, it entails<br />

sharing our story with the next<br />

generation. It is precisely through<br />

a fealty to mesorah that we have a<br />

connection that transcends generations<br />

and a collective story to share.<br />

Without the mesorah of learning,<br />

with its internal logic and intellectual<br />

rigor, and the mesorah of practice,<br />

A Personal Account of The Rav on Mesorah<br />

The old Rebbe walks into the classroom crowded with students who are young enough to be his grandchildren.<br />

He enters as an old man with wrinkled face, his eyes reflecting the fatigue and sadness of old age. You have to be<br />

old to experience this sadness. It is the melancholy that results from an awareness of people and things which have<br />

disappeared and linger only in memory. I sit down; opposite me are rows of young beaming faces with clear eyes<br />

radiating the joy of being young. For a moment, the Rebbe is gripped with pessimism, with tremors of uncertainly.<br />

He asks himself: Can there be a dialogue between an old teacher and young students, between a Rebbe in his Indian<br />

summer and students enjoying the spring of their lives? The Rebbe starts his shiur, uncertain as to how it will proceed.<br />

Suddenly the door opens and an old man, much older than the Rebbe, enters. He is the grandfather of the Rebbe,<br />

Reb Chaim Brisker. It would be most difficult to study Talmud with students who are trained in the sciences and<br />

mathematics, were it not for his method, which is very modern and equals, if not surpasses, most contemporary<br />

forms of logic, metaphysics or philosophy. The door opens again and another old man comes in. He is older than Reb<br />

Chaim, for he lived in the 17th century. His name is Reb Shabtai Cohen, known as the Shach, who must be present<br />

when dinai mamonot (civil law) is discussed. Many more visitors arrive, some from the 11th, 12th and 13th centuries,<br />

and others harking back to antiquity – Rabbeinu Tam, Rashi, Rambam, Raavad, Rashba, Rabbi Akiva and others.<br />

These scholarly giants of the past are bidden to take their seats. The Rebbe introduces the guests to his pupils, and<br />

the dialogue commences. The Rambam states a halacha; the Raavad disagrees sharply, as is his wont. Some students<br />

interrupt to defend the Rambam, and they express themselves harshly against the Raavad, as young people are apt to<br />

do. The Rebbe softly corrects the students and suggest more restrained tones. The Rashba smiles gently. The Rebbe<br />

tries to analyze what the students meant, and other students intercede. Rabeinu Tam is called upon to express his<br />

opinion, and suddenly, a symposium of generations comes into existence. Young students debate earlier generations<br />

with an air of daring familiarity, and a crescendo of discussion ensues.<br />

All speak one language; all pursue one goal; all are committed to a common vision; and all operate with the same<br />

categories. A Mesorah collegiality is achieved, a friendship, a comradeship of old and young, spanning antiquity,<br />

the Middle Ages and modern times. This joining of the generations, this march of centuries, this dialogue and<br />

conversation between antiquity and the present will finally bring about the redemption of the Jewish people.<br />

After a two or three hour shiur, the Rebbe emerges from the chamber young and rejuvenated. He has defeated age. The<br />

students look exhausted. In the Mesorah experience, years play no role. Hands, however parchment-dry and wrinkled,<br />

embrace warm and supple hands in commonality, bridging the gap with separates the generations. Thus, the “old ones”<br />

of the past continue their great dialogue of the generations, ensuring an enduring commitment to the Mesorah.<br />

Reflections of the Rav Vol. II pp. 22-23<br />

12<br />

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • The Benjamin and Rose Berger CJF Torah To-Go Series • Pesach 5776

with its traditional values and profile,<br />

Judaism would have no future. It is<br />

precisely due to our commitment to<br />

mesorah that enables each of our seder<br />

stories to unite as one eternal story of<br />

Knesset Yisrael.<br />

Addendum<br />

Perhaps the role of mesorah in the<br />

Hagadah explains an overarching<br />

peculiarity about the Hagadah. The<br />

mitzvah of sippur yetziat Mitzrayim—<br />

retelling the Exodus from Egypt — is<br />

derived from the verse (Shemot<br />

בעבור זה עשה ה' לי בצאתי (13:8<br />

— Because of this, God did ממצרים<br />

this for me when I left Egypt. The<br />

Mishna (Pesachim 116b) takes notice<br />

of the first-person language of the<br />

verse and requires each one of us to<br />

personalize the story. The Hagadah<br />

itself emphasizes this point when it<br />

cites the aforementioned verse toward<br />

the culmination of maggid charging us<br />

with the responsibility that we must<br />

see ourselves as if we personally and<br />

individually had left Egypt.<br />

It is, therefore, interesting that the<br />

main text of the Hagadah — the<br />

means by which we tell this story<br />

itself — is fixed and rigid. While<br />

seder tables vary widely in their<br />

style, character, and experience, the<br />

traditional core text of the Hagadah<br />

remains standard throughout the<br />

Torah world and has attracted more<br />

commentaries than perhaps any other<br />

Torah work. Why would a mitzvah<br />

which is supposedly so individual and<br />

personal be limited to a specific text?<br />

How can it be that the core of each<br />

and every person’s story at the seder is<br />

the same the world over?<br />

In light of our understanding of the<br />

role of mesorah in the Hagadah, we<br />

can appreciate this as well. Without a<br />

unifying mesorah text, each generation<br />

would be a standalone unit, disjointed<br />

from previous and subsequent eras,<br />

and every individual would be merely<br />

an individual, without a connection to<br />

the greater Knesset Yisrael. 11 If every<br />

person at their seder table would fulfill<br />

the mitzvah of sippur yetziat Mitzrayim<br />

by creating their own text, then their<br />

story would be personal and unique,<br />

but it would be theirs alone. By sharing<br />

a mesorah text, the story that I share<br />

in my unique way at my unique seder<br />

table is not only my story, but it is part<br />

of a larger story of the entire Jewish<br />

people. 12 Yes, every person’s retelling of<br />

the Exodus is unique, in fulfillment of<br />

— כל המרבה הרי זה משובח the principle<br />

which encourages an individual to add<br />

their personal touch to the story. At the<br />

same time, through a shared mesorah,<br />

my personal story is transformed into a<br />

transcendent, eternal story of the ages.<br />

Notes<br />

1. See Ramban’s introduction to his<br />

commentary Milchamot Hashem regarding the<br />

difficulty of creating an irrefutable proof.<br />

2. See Talmud Bavli, Gittin 59b.<br />

3. See the Rama, O.C. 472:4 who notes that<br />

women did not have the practice to recline<br />

because they relied on the opinion that since<br />

today reclining does not reflect freedom it<br />

should not be done at all.<br />

4. The full audio of the shiur is available at:<br />

http://www.yutorah.org/lectures/lecture.<br />

cfm/767722/.<br />

5. This talk was delivered at the Anshei<br />

Brisk synagogue in Brooklyn, New York on<br />

Shabbat Parshat Behaalotecha 5703. It was<br />

transcribed by Rabbi Shmuel Aharon Pardes<br />

and published in Hapardes no. 17. Vol. 11.<br />

6. For this reason, the Rambam (Hilchot<br />

Mamrim, Perek 2) places clear limits on<br />

the ability of the sages to exact rules on the<br />

community unilaterally. The sages may not<br />

enact a decree that majority of the community<br />

cannot follow and if they do enact such a<br />

decree, it is not binding.<br />

7. There is a symbiotic relationship between<br />

the communal practice and Rabbinic<br />

leadership that establishes mesorah. In some<br />

cases, it is unclear which came first, the<br />

communal practice or Rabbinic enactment,<br />

such as the practice of Jewish women to<br />

observe seven clean days (see Ritva and Meiri,<br />

Berachot 31a).<br />

8. This explanation is similar to those of the<br />

Ri ben Yakar, Siddur Rashi and Meyuchas<br />

LiRashi commentaries on the Hagadah, in the<br />

Toras Chaim edition of the Hagadah.<br />

9. Rabbi Elazar ben Azarya also refers to<br />

himself as being “like seventy years old,”<br />

which Ritva and many other Hagadah<br />

commentaries in the Rishonim understand<br />

as a reference to the Talmud’s tradition that<br />

he grew a hoary beard once appointed as the<br />

new Chief Rabbi. See also Hagadah of Rabbi<br />

Jonathan Sacks.<br />

10 . The Talmud (Shabbat 59b) suggests that<br />

even a heavenly voice and Divine intervention<br />

do not establish normative communal practice<br />

without consensus of the sages, as occurred<br />

in the dispute between Rabbi Eliezer and<br />

the sages. This concept was taught by Akavia<br />

ben Mahalalel to his son in his final hours, as<br />

described by the Mishna in Eduyot chapter 5.<br />

11 . This concept is true of other core mesorah<br />

texts, such as the Talmud Bavli, whose<br />

words and pages have survived and thrived<br />

for centuries and it connects all those who<br />

have studied it throughout the generations.<br />

Obviously, the text of the Hagadah developed<br />

over generations, much like the Talmud;<br />

the uniformity and ubiquity of the text that<br />

coalesced matched the increasing need for<br />

stronger mesorah with increased dispersion.<br />

12 . This suggestion was offered by Rabbi Dr.<br />

Avi Oppenheimer.<br />

Find more shiurim and articles from Rabbi Reuven Brand at<br />

http://www.yutorah.org/Rabbi-Reuven-Brand<br />

13<br />

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • The Benjamin and Rose Berger CJF Torah To-Go Series • Pesach 5776

In Time, Out of Time, or<br />

Beyond Time? Women and<br />

Sefiras HaOmer<br />

It is a well-known and oft-discussed<br />

feature of Jewish law that women<br />

are exempt from certain mitzvos,<br />

identified by the categorical name<br />

of mitzos asei she-ha-zman gramman,<br />

roughly translatable as “positive<br />

commandments that are caused by<br />

time,” or more loosely as “time-bound<br />

positive commandments.” 1 Many<br />

of these commandments and their<br />

applicability to women have been the<br />

subject of extensive discussion and<br />

debate. However, one mitzvah that is<br />

often overlooked in the debate, and<br />

perhaps forgotten, is the very mitzvah<br />

we most worry about forgetting:<br />

sefiras ha-omer.<br />

At first glance, there should be<br />

nothing to talk about: sefiras ha-omer<br />

is clearly a time-bound mitzvah, if<br />

there ever was one. It is applicable<br />

only seven weeks a year. During that<br />

time, it is performed once a day, and<br />

that performance can only take place<br />

on that specific day of the omer.<br />

Further, according to some Rishonim,<br />

the obligation can only be fulfilled<br />

at night. 2 Aside from the technical<br />

details, sefiras ha-omer is uniquely<br />

pressured from a time perspective:<br />

as alluded to above, it brings with<br />

it the constant anxiety that if it is<br />

not accomplished within a certain<br />

window, there will be consequences<br />

for the entire year’s omer cycle, in the<br />

loss of a berachah and perhaps the<br />

mitzvah itself, in whole or in part. It<br />

would seem that there is more than<br />

enough reason to safely place this<br />

mitzvah in the time-bound category.<br />

Indeed, this is the position held by<br />

Rishonim such as the Rambam 3 and<br />

the Sefer HaChinuch. 4<br />

And yet here, as is so often the case,<br />

we are surprised by the words of the<br />

Ramban. The Talmud, in a source that<br />

could be considered “zman gerama”<br />

due to its recent appearance in the<br />

Daf Yomi, 5 provides a list of mitzvos<br />

that are obligatory upon women,<br />

as they are non-time dependent.<br />

Commenting on this list, the Ramban<br />

observes that it is not exhaustive.<br />

There are mitzvos that are obligatory<br />

for women, and yet are not included,<br />

such as for example, kibbud av v’eim,<br />

mora av v’eim, and ... sefiras ha’omer.<br />

The Ramban’s words demand<br />

attention both in terms of analysis<br />

and application. Regarding the latter,<br />

normative halachah appears to claim<br />

Rabbi Daniel Z. Feldman<br />

Rosh Yeshiva, RIETS<br />

Rabbi, Congregation Ohr Sadya, Teaneck, NJ<br />

that women are exempt from sefiras<br />

ha-omer as a time-bound mitzvah, but<br />

the matter does not end there.<br />

Many of the Ashkenazic Rishonim 6<br />

are of the view that women are<br />

permitted to volunteer to perform<br />

the mitzvos that exempt them, and to<br />

do so with a berachah. Thus, it would<br />

seem that sefiras ha-omer, with a<br />

berachah, should be allowed, as the<br />

Arukh HaShulchan in fact maintains.<br />

Further, the Magen Avraham asserts<br />

that women have accepted upon<br />

themselves sefiras ha-omer as an<br />

obligation. 7 Some 8 compare this<br />

notion to the contemporary attitude<br />

toward the Ma’ariv prayer: despite the<br />

fact that the Talmud identifies it as a<br />

“reshut,” many Rishonim assert that it<br />

is now accepted as obligatory. While<br />

the position of the Ramban does not<br />

seem to dictate the halachah, it might<br />

be influencing practice nonetheless;<br />

it could be argued that this mitzvah,<br />

from among those that are timebound,<br />

should be singled out for<br />

14<br />

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • The Benjamin and Rose Berger CJF Torah To-Go Series • Pesach 5776

voluntary acceptance in deference to<br />

his view, as sefiras ha-omer is unique<br />

among time-bound mitzvos due to<br />

the existence of a major authority who<br />

believes it is incumbent upon women.<br />

However, the Mishnah Berurah 9 asserts<br />

that the practice as he encounters it is<br />

against the Magen Avraham, and that<br />

women have no obligation in sefiras<br />

ha-omer, voluntary or otherwise. In<br />

addition, he asserts that the mitzvah<br />

should be differentiated from other<br />

mitzvos shehzman gramman in the<br />

other direction, in that women should<br />

not make a berachah, despite the<br />

view of the Ashkenazic authorities to<br />

allow such recitation. This view, which<br />

is attributed to the sefer Shulchan<br />

Shlomo, is explained by a concern that<br />

the woman in question will “certainly<br />

omit [at least] one day.”<br />

This appears to be a reference to the<br />

view of Rishonim, adopted by the<br />

Shulchan Arukh, 10 that one does not<br />

continue counting the omer with a<br />

berachah if one misses a complete<br />

day. The implication is that sefiras<br />

ha-omer is one integrated mitzvah of<br />

49 counted days, and thus any omitted<br />

day invalidates the whole mitzvah,<br />

rendering a berachah unjustified.<br />

If that is true of the days after the<br />

omitted day, then it should also be<br />

true retroactively: all the earlier<br />

berachos were also unwarranted. 11<br />

One who is obligated in the mitzvah<br />

has no choice but to assume this<br />

risk. However, if one is not obligated,<br />

perhaps this is not an appropriate<br />

candidate for volunteering, given the<br />

risk of multiple unjustified berachos.<br />

However, it is possible to take a<br />

different view for a number of reasons.<br />

One possibility is the position of some<br />

authorities that there is no such thing<br />

as a retroactive berachah le-vatalah;<br />

any berachah that was justified at the<br />

time of its recital is valid, regardless of<br />

anything that happens later to cast the<br />

relevant mitzvah into doubt. 12<br />

Further, there are those, such as Rav<br />

Soloveitchik, who understood the<br />

discontinuation of a berachah when<br />

a day is omitted in a fundamentally<br />

different way. In this understanding,<br />

the berachah is discontinued not<br />

because the mitzvah is one unit, but<br />

rather because counting cannot exist<br />

without building on a continuous<br />

preceding process. If so, the berachah<br />

is only problematic prospectively;<br />

there is no impact on any earlier day,<br />

and thus no reason to hesitate starting<br />

the count with a berachah, even if one<br />

knew that it was likely or even definite<br />

that a day will be missed down the<br />

line.<br />

R. Yisrael David Harfenes 13 was not<br />

worried about the Mishneh Berurah’s<br />

concerns, suggesting that it is possible<br />

to set up a system of reminders to<br />

mitigate the likelihood of forgetting<br />

a day. Further, after noting the<br />

possibilities mentioned above that<br />

there is no such thing as a retroactive<br />

berachah levatalah, or that sefiras<br />

ha-omer itself does not pose this<br />

issue, he observes that the Mishneh<br />

Berurah’s source, the Shulchan Shlomo,<br />

is itself not actually concerned about a<br />

retroactive berachah levatalah. Rather,<br />

examining that source in the original,<br />

it becomes clear that the fear was<br />

that the woman in question would<br />

miss a day, and would then continue<br />

counting with a berachah, unaware<br />

that it is against the accepted halachah.<br />

To this, R. Harfenes asserts, there is<br />

an easy remedy: teach the halachah<br />

in its totality, so she can count in<br />

confidence, and know what to do if a<br />

day is indeed omitted. 14<br />

Aside from the question of<br />

practice, there remains the task of<br />

understanding the foundation of the<br />

Ramban’s position: why, after all is<br />

said and done, should sefiras ha-omer<br />

be classified as a non-time-bound<br />

mitzvah? Attempting to answer this<br />

question could yield insights about<br />

sefiras ha-omer, about mitzvos aseh<br />

shehazman gramman, or both.<br />

The bluntest approach to the Ramban<br />

is that of the Shut Divrei Malkiel<br />

(V, 65), who simply declares the<br />

statement to be a typographical error,<br />

a taus sofer. However, even a sweeping<br />

theory such as that needs to provide<br />

an alternative for what the text should<br />

have said, and thus we are given two<br />

possibilities: either it should have<br />

been included among the exemptions,<br />

rather than the obligations; or the<br />

text should have instead referred to<br />

the bringing of the omer, which, as a<br />

sacrificial offering, presumably applies<br />

to women as well. 15<br />

Others point to the majority view<br />

among the Rishonim (against that of<br />

the Rambam) that sefiras ha-omer is a<br />

Rabbinic mitzvah in the modern era,<br />

and that its original Torah mandate<br />

does not apply in the absence of the<br />

Beis HaMikdash. This fact may have<br />

both specific and general reasons for<br />

relevance. From a general perspective,<br />

some Rishonim maintain that only<br />

Torah mitzvos that are time-bound<br />

exempt women; this exemption<br />

does not apply to Rabbinic mitzvos,<br />

even if they are time-bound. 16 This<br />

view is interesting, because one<br />

would have expected the rabbis to<br />

continue the Torah’s policy in this<br />

area, as they generally pattern their<br />

enactments after Torah law. To draw<br />

a distinction in this way is to suggest<br />

that the Torah did not exempt timebound<br />

obligations because of the<br />

fact of being time-bound, but rather<br />

exempted a small number of mitzvos<br />

15<br />

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • The Benjamin and Rose Berger CJF Torah To-Go Series • Pesach 5776

for other reasons, and they happen to<br />

be identifiable through the common<br />

feature of being time-bound.<br />

A more specific relevance might<br />

be if the Rabbinic mitzvah is<br />

fundamentally different than the<br />

Torah mitzvah. Perhaps the rabbis<br />

The word tamim has multiple<br />

connotations. In the context<br />

of temimot for sefirat<br />

ha’omer, it means whole. In<br />

the context of tamim tihiyeh,<br />

it means innocent or pure.<br />

R. Aharon Kotler, Mishnat<br />

Rabbi Aharon Al HaTorah,<br />

Mishpatim, notes that<br />

innocence and purity were<br />

key components of accepting<br />

the Torah. The Gemara,<br />

Shabbat 88a, records a<br />

conversation between a<br />

Tzduki (Sadducee) and<br />

Rava. The Tzduki criticizes<br />

Rava’s nation for being<br />

foolish for accepting the<br />

Torah before listening to<br />

what was in it. What if the<br />

Torah would have been too<br />

hard to keep? Rava responds<br />

that we walk with temimut<br />

and lovingly accept the fact<br />

that God won’t demand<br />

of us anything we can’t<br />

fulfill. R. Kotler notes that<br />

Rava’s attitude toward the<br />

acceptance of the Torah is<br />

the attitude that the Torah<br />

expects from all us as part of<br />

the mitzvah of tamim tihiyeh.<br />

Torah To Go Editors<br />

did not simply continue the Torah<br />

obligation despite the lack of the Beis<br />

HaMikdash; rather, they mandated<br />

counting as part of a different, broader<br />

obligation to remember the Beis<br />

HaMikdash, a mitzvah that may not in<br />

its totality be time dependent.<br />

Another avenue to pursue is the<br />

possibility that sefiras ha-omer has the<br />

properties of a time-bound mitzvah,<br />

but is nonetheless somehow imposed<br />

upon women by textual declaration<br />

(as is the case with Kiddush and<br />

matzah on Pesach night). To this end,<br />

attention is drawn to the verse 17 that<br />

obligates both the counting of the<br />

omer and the bringing of the omer:<br />

these are to happen on the second<br />

day of Pesach, identified in the Torah<br />

as mimacharas haShabbos. R Eliyahu<br />

Shlesinger 18 notes that the Torah does<br />

not use a numerical date to place the<br />

obligation, distancing the mitzvah<br />

from a time period linguistically if<br />

not practically. The Avnei Nezer 19<br />

suggests that the linking to Pesach<br />

attaches the mitzvah of sefirah to the<br />

obligations of Pesach; as women are<br />

obligated in those, perhaps they also<br />

are included in sefirah. R. Avraham<br />

David Horowitz 20 suggests that since<br />

the bringing of the omer permits the<br />

eating of chadash, which is otherwise<br />

a prohibition, the whole package can<br />

be considered a negative mitzvah<br />

rather than a positive one, and women<br />

should be obligated for that reason.<br />

Others suggest that the general<br />

exemption of time-bound<br />

commandments does indeed stem<br />

from the character of being timebound<br />

(rather than that of being<br />

simply an identifying element, as<br />

suggested above), and within that<br />

perspective find reason to differentiate<br />

here. For example, the position of the<br />

Abudraham and the Kol Bo is that the<br />

exemption is due to the concern that<br />

mitzvos that demand attention at a<br />

certain time will detract from family<br />

responsibilities. If so, some suggest,<br />

a mitzvah such as sefiras ha-omer,<br />

which is performed quickly with a<br />

simple verbal declaration, might be<br />

excluded from this category, or at<br />

least be an appropriate candidate for<br />

voluntary performance. 21<br />

Many of the above approaches<br />

share a fundamental difficulty. The<br />

Ramban, whose words provoke the<br />

entire discussion, does not say that<br />

sefiras ha-omer is an exception, but<br />

that it is simply not a mitzvas aseh<br />

shezman grama. Accordingly, the most<br />

fitting explanation would be one that<br />

addresses that element directly. The<br />

Turei Even 22 provides a prominent<br />

example of this kind of approach.<br />

Building on the related example of<br />

bikkurim, he asserts that a mitzvah is<br />

only in this category when it could<br />

have by its nature been performed<br />

at any time, but the Torah imposed<br />

a limited timeframe. However, if<br />

the limitation is a response to a<br />

temporal reality, that is not called<br />

zman gerama. In this case, one can<br />

only count the days of the omer when<br />

they are actually happening (which<br />

is itself prompted by the bringing of<br />

the omer). Similarly, the Sridei Eish 23<br />

expresses it by stating that the timing<br />

here is not the timeframe for the<br />

mitzvah, but rather the mitzvah itself.<br />

This notion may have particular<br />

relevance to the mitzvah of sefiras<br />

ha-omer. It is possible to argue<br />

that the entire mitzvah of counting<br />

the omer is to take the existing<br />

calendar and superimpose upon it<br />

a new framework, one that doesn’t<br />

mark time by any of the standard<br />

milestones, but rather by the<br />

perspective of anticipating the giving<br />

16<br />

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • The Benjamin and Rose Berger CJF Torah To-Go Series • Pesach 5776

of the Torah. 24 Thus, this mitzvah<br />

does not happen within time; rather,<br />

it transforms the nature of time<br />

itself. A specific day is no longer<br />

just a Tuesday, or a date in Iyar, but<br />

is identified as a step toward the<br />

receiving of the Torah. It becomes,<br />

in essence, a new vantage point from<br />

which all else can be perceived. The<br />

mitzvah is, in essence, not to let time<br />

define us, but for us to define the time.<br />

Within that context, it is worth noting<br />

that a crucial word in the Torah’s<br />

commandment of sefiras ha-omer<br />

is “temimos,” meaning perfect or<br />

complete, a word that has had major<br />

impact on the practical application<br />

of this mitzvah. This word, in other<br />

forms, appears elsewhere in the<br />