Alice Moore Dunbar-Nelson: “The Praline Woman”

Posted: February 2, 2014 | Author: Zócalo Poets | Filed under: Alice Moore Dunbar-Nelson, Creole: American (Louisiana), English: Nineteenth-century Black-American Southern Dialect | Tags: Black History Month |Comments Off on Alice Moore Dunbar-Nelson: “The Praline Woman”Alice Moore Dunbar-Nelson(1875-1935)

“The Praline Woman”

(from: The Goodness of St. Rocque and Other Short Stories, published in 1899)

[ On title page: “To my best comrade – My husband [Paul Laurence Dunbar]” ]

.

Editor’s Note:

French settlers brought the Praline recipe to Louisiana where both sugar cane and pecan trees were plentiful. During the 19th century, chefs in New Orleans substituted pecans for the originally-used almonds, and added cream to thicken the confection. They thus created what became known throughout the American South as the Praline. Pralines have a creamy consistency, similar to fudge. They are most often made combining brown sugar, butter, and cream or buttermilk in a pot on medium-high heat, and stirring constantly until most of the water has evaporated and the mass reaches a thick texture of a brownish colour. The mixture then cools down and hardens somewhat, then is ready to eat.

.

The Creole people of Louisiana are descended from 18th-century colonial settlers of French – and sometimes Spanish – descent, with those of African descent via American slavery. Many Creoles in the 19th century were mixed-race people. This also included Native-American ancestry in some families. The word Creole itself has many different meanings, depending on which country, culture, and language where it is in use – throughout The Americas.

.

A note on the language employed by Dunbar-Nelson:

The author has created a hybrid language of her own here, combining Black-American Southern Dialect with Louisiana (French-based) Creole (primarily translated into ‘accented’ English) – so that her English-speaking readers might enjoy reading what for most would be a narrative of home-grown “exotica”.

. . .

“The Praline Woman”

.

The praline woman sits by the side of the Archbishop’s quaint little old chapel on Royal Street, and slowly waves her latanier fan over the pink and brown wares.

“Pralines, pralines. Ah, ma’amzelle, you buy? S’il vous plait, ma’amzelle, ces pralines, dey be fine, ver’ fresh.

“Mais non, maman, you are not sure?

“Sho’, chile, ma bébé, ma petite, she put dese up hissef. He’s hans’ so small, ma’amzelle, lak you’s, mais brune. She put dese up dis morn’. You tak’ none? No husban’ fo’ you den!

“Ah, ma petite, you tak’? Cinq sous, bébé, may le bon Dieu keep you good!

“Mais oui, madame, I know you étrangér. You don’ look lak dese New Orleans peop’. You Lak’ dose Yankee dat come down ‘fo’ de war.”

Ding-dong, ding-dong, ding-dong, chimes the Cathedral bell across Jackson Square, and the praline woman crosses herself.

“Hail, Mary, full of grace–

“Pralines, madame? You buy lak’ dat? Dix sous, madame, an’ one lil’ piece fo’ lagniappe fo’ madame’s lil’ bébé. Ah, c’est bon!

“Pralines, pralines, so fresh, so fine! M’sieu would lak’ some fo’ he’s lil’ gal’ at home? Mais non, what’s dat you say? She’s daid! Ah, m’sieu, ‘t is my lil’ gal what died long year ago. Misèrè, misère!

“Here come dat lazy Indien squaw. What she good fo’, anyhow? She jes’ sit lak dat in de French Market an’ sell her filé, an’ sleep, sleep, sleep, lak’ so in he’s blanket. Hey, dere, you, Tonita, how goes you’ beezness?

“Pralines, pralines! Holy Father, you give me dat blessin’ sho’? Tak’ one, I know you lak dat w’ite one. It tas’ good, I know, bien.

“Pralines, madame? I lak’ you’ face. What fo’ you wear black? You’ lil’ boy daid? You tak’ one, jes’ see how it tas’. I had one lil’ boy once, he jes’ grow ‘twell he’s big lak’ dis, den one day he tak’ sick an’die. Oh, madame, it mos’ brek my po’ heart. I burn candle in St. Rocque, I say my beads, I sprinkle holy water roun’ he’s bed; he jes’ lay so, he’s eyes turn up, he say ‘Maman, maman,’ den he die! Madame, you tak’ one. Non, non, no l’argent, you tak’ one fo’ my lil’ boy’s sake.

“Pralines, pralines, m’sieu? Who mak’ dese? My lil’ gal, Didele, of co’se. Non, non, I don’t mak’ no mo’.

Po’ Tante Marie get too ol’. Didele? She’s one lil’ gal I’dopt. I see her one day in de strit. He walk so; hit col’ she shiver, an’ I say, ‘Where you gone, lil’ gal?’ and he can’ tell. He jes’ crip close to me, an’ cry so! Den I tak’ her home wid me, and she say he’s name Didele. You see dey wa’nt nobody dere. My lil’ gal, she’s daid, of de yellow fever; my lil’ boy, he’s daid, po’ Tante Marie all alone. Didele, she grow fine, she keep house an’ mek’ pralines. Den, when night come, she sit wid he’s guitar an’ sing:

“‘Tu l’aime ces trois jours,

Tu l’aime ces trois jours,

Ma coeur à toi,

Ma coeur à toi,

Tu l’aime ces trois jours!’

“Ah, he’s fine gal, is Didele!

“Pralines, pralines! Dat lil’ cloud, h’it look lak’ rain, I hope no.

“Here come dat lazy I’ishman down de strit. I don’t lak’ I’ishman, me, non, dey so funny. One day one I’ishman, he say to me, `Auntie, what fo’ you talk so?’ and I jes’ say back, ‘What fo’ you say “Faith an’ be jabers”?’ ‘Non, I don’t lak I’ishman, me!

“Here come de rain! Now I got fo’ to go. Didele, she be wait fo’ me. Down h’it come! H’it fall in de Meesseesip, an’ fill up– up–so, clean to de levee, den we have big crivasse, an’ po’ Tante Marie float away. Bon jour, madame, you come again? Pralines! Pralines!“

. . .

Source for the short story above: the online archives of The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture (Harlem, New York City)

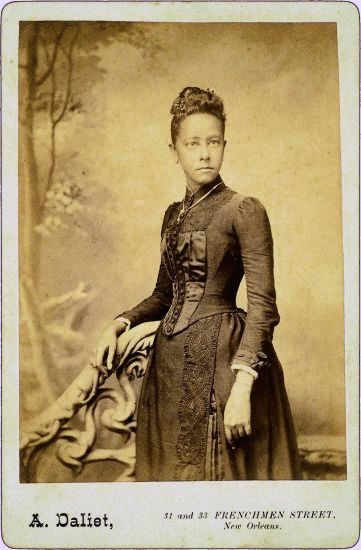

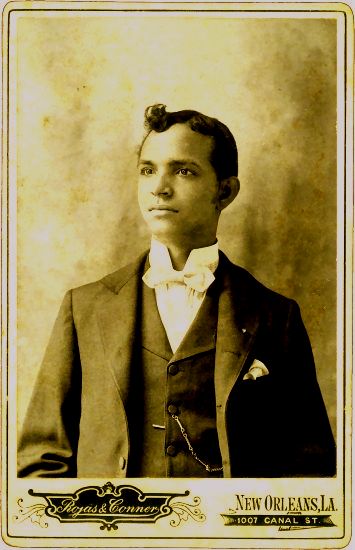

Photographs: A 19th-century Creole woman, New Orleans / A 19th-century Creole man, New Orleans

. . . . .