The opening page of Rhode Island blacksmith “Nailer Tom” Hazard’s diary includes an entry for June 21, 1778, during the American Revolutionary War. At the time, the British occupied Newport. Hazard records a typical voyage of a flag, a transport vessel that was authorized to sail by American and British military authorities. The ship hauled off that morning from “Tom Robinsons whaf” at Newport and anchored off Fort Point by nightfall. The next morning, they set sail again, and arrived off Warwick Point around sunset.

A Black man, free or enslaved, it is not known, had died on board the vessel. A party rowed out from the ship toward the shore. Nailer Tom records the event in what would be the Quaker’s customary, terse, matter-of-fact manner: “George Coggishall[1], Negro man died on Board, we Buried him on the beach, the Son was in the clips.”[2]

This small incident recorded during the colonial era is one of but many circumstances in which many Black individuals, considered mere property, were buried in innumerable, now anonymous places of Rhode Island and the rest of New England. While the quick burial on a beach was the fate of many slaves who died conveniently near an island or peninsula, those who arrived and labored on plantations were buried in designated plots on the property, or in larger, designated areas known only to locals as “the slave burial ground”, or “old indian burial ground’, as existing indigenous gravesites were also employed for use as slave burial grounds.

Burial Point lies just south of Mill Cove at the entrance to Mill Creek in North Kingstown (Robert Geake)

In later public cemeteries, the lots where enslaved persons were buried expanded into the “potter plots” of the 19th and 20th centuries. As lands were sold within the urban areas, both family and slave plots within towns and cities were dug up and the remains and gravestones moved into the public cemetery. There, enslaved persons were further separated from white burial grounds, or in some cases, forgotten completely.

Rhode Island was foremost in the population of enslaved people per capita in New England during the colonial period. While there are some known burial sites for the enslaved in the state, other traces are hidden among the remaining woods and suburban sprawl, as well as those of which there is now no visible trace remaining.

By 1760, Rhode Island vied with North Carolina in holding a similar number of enslaved laborers in the colonies. During the peak of plantation activity, the greatest population of these resided on the so called Narragansett Plantations in what is now South County.

In many cases, even after manumission in the last quarter of the 18th century, former field hands or domestic enslaved people continued to work on the farms where they had lived.

When they died, they were buried in the same lots with others who had never gained their freedom. Even if they had left the plantation and earned a living on their own, if their estate did not set aside funds a burial plot, they often were often consigned to the burial ground on the plantation where they had been held captive.

Author Glenn A Knoblock, in his African American Historic Burial Grounds and Gravesites of New England, notes that “New England slave owners seem to have given the enslaved some measure of latitude and freedom in their burial practices.” He adds:

The body of an enslaved individual would have been washed and prepared for burial by a family member or other individual with special training (as was the case in African society)and watched over at night prior to its burial in a day or two.[3]

In places such as North Kingstown and Newport, where a large black community of free and enslaved people had already endured for generations, the organizing of funerals was conducted by an “undertaker,” a term more specific to the tasks of arranging the memorial service and burial of the deceased, most often in partnership with the church sexton.

Again, Knoblock shows that the practices of the enslaved were often similar to their masters:

For the enslaved and free alike in early New England, a proper African funeral service was considered important so that the deceased could live properly after death, a failure to do so meaning that the deceased might become a wandering ghost that could hurt or harm the living.[4]

The sprawling grounds of Cocumscussoc in North Kingstown, better known for its mid-18th century Georgian manor house called “Smith’s Castle,” held an indigenous burial ground at a site close by a cove and the mouth of what was then called Sawmill Creek. Long known to locals, the burial site was used for the enslaved persons who lived and worked the plantation for many years, and may also have seen additional burials of indigenous people and domestic enslaved persons from the community.

The site was listed as “the burying point” on an 1802 survey, and officially documented in 1883 by George Harris in his handwritten book Anciente Burial Grounds of Olde Kingstowne. Harris counted 72 large graves and 8 smaller graves within the plot, and speculated that there may have been other stones, which were removed. All of these were crude markers for the men, women, and children who spent their lives working at Cocumscussoc, but also likely at other nearby farms, based on the high number of graves at the burial point.

An old stone dock, merely referenced at the time of the Harris map as being built sometime before 1800, jutted out from the point to a deep channel. It was a place that a neighbor, Harriett Spink Smith, frequently visited. The long-time North Kingstown resident kept a near lifelong diary of happenings in the town, writing wistfully as she revisited the site as an elderly woman:

Nov. 1888 – The old Indian Burying Place, I crossed or passed once more. There must have been nearer 200 than 100 graves in the early days. But now it having been out “to the commons” so long, most of the rough stones broken down. “Tony, son of Tony and Amey Moffatt,” aged 6 years, died in 1764, I think. His engraved head stone flat on ground.[5]

Smith’s diary refers to what was likely one of the oldest slave burial grounds in Rhode Island, as the plantation was owned by the Smith/Updike family from 1651 to 1813. Just inland from “the old burying point” lies the Aryault-Updike and Congdon burial lots, both fenced in with iron rails and granite posts dating from the 19th century. A triangular stone, much repaired, is a marker for the grave of Richard Smith, the founder of Smith’s Castle.

It is unknown if any of the nine enslaved men, children, and one woman whom Richard Smith, Jr. owned during his transitioning of the trading post to a working plantation are buried here. He had manumitted them in his will, after his death in 1692. Still, most of the enslaved people who died at Cocumscussoc during that time and through the next three generations of ownership would likely have been buried at this site.

The slave burial ground was leveled in the early 20th century when the nearby Devil’s Foot ledge was quarried for its granite. The State needed the granite brought to Newport for projects, and had a road constructed to the site of the old dock, which they then improved and used to load the granite onto ships for transport.[6]

Many other “slave lots” were recorded to be in a run-down and overgrown condition by James N. Arnold and George J. Harris in the 1880’s as they compiled the first farm-by-farm survey of private cemeteries in the region. Their works were especially useful to the Rhode Island Genealogical Society’s modern efforts to update the status of these historic cemeteries in South Kingstown, Exeter, Westerly, Newport, Warwick, and Providence.

The Monument to the enslaved persons of the Waterman family (Courtesy of the Rhode Island Historical Cemetery Commission)

Among the other plantation owners in South County, the Gardiners were a prominent family. Nearly all were descendants of Squire Nicholas Gardner (1738-1815). The Gardner/Stanton enslaved burial ground, which originally lay on land in both North and South Kingstown, contains many of the graves of the family’s former enslaved persons. A description of the now lost burial plot written by James N. Arnold in 1880 reads:

A short distance north of the old house . . . is a colored burial yard- graves that have no protection and marked with rude stones only. In this yard are buried two well-known old darkies, servants formerly of Squire Nicholas Gardner who gave them a horse on his decease.[7]

It is unknown whether these two “well-known” Black men were the former enslaved laborers who had served in the Revolutionary War. In the years after the American victory their wartime service was often acknowledged in the communities where they lived, and in the obituaries published after their deaths.[8]

Primus Gardner served as a private in Captain Dexter’s company in the First Rhode Island Regiment which included formerly enslaved men who earned their freedom by enlisting in the regiment for the duration of the war. He died during the war on October 20, 1780. Rutter Gardner served in the regiment with Captain Lewis’ company. He appears to have served out his time with the regiment and likely was injured or became ill during his time of service. He is listed as “sick” in North Kingstown in March of 1779, and was discharged from service in April of that year. His illness or injuries seem to have continued to plague him, for on March 28, 1785, Hezekiah Babcock submitted a bill to the town of Hopkinton for the “boarding and nursing of Rutter Gardner, a negro man who formerly belonged to Nicholas Gardner of Exeter, and a late soldier in the Rhode Island Continental Regiment.”[9]

“Here Lieth Edward Negro Servant to Henry Collins, died Febry 16th 1730 in ye 21st year of his age. He was faithfull and well beloved of his Master.” God’s Little Acre, Newport (Christian McBurney)

Another enslaved laborer, Hercules Gardner, enlisted in the “Black” Regiment and thereby earned his freedom. He served in Captain Thomas Cole’s company. Eventually, he was transferred to the “Corps of Invalids”, a unit of soldiers in the Continental Army needing to recover from illness or wounds and afforded light duty.

Another dozen enslaved persons of other members of the Gardner family appear on the rolls of the regiment in Forgotten Patriots, a Daughters of the American Revolution, a publication that compiles the names of African American and indigenous soldiers who served in the American Army during the Revolutionary War. Whether for three months in the militia or state regiment, or three years or the duration of the war, each had served time in the cause to earn his own freedom, and for the independence of their country.[10]

The Babcock family slave lot was examined by Arnold on October 6, 1880, on “land owned by Mrs. Randall” [now Tuckertown Park outside Wakefield]. It is said that north of the Randall barn was an old slave burial ground that has disappeared and that is said to have contained the graves of persons enslaved by the white Babcock family.

More veterans lay in this cemetery. One of Hezekiah Babcock’s enslaved named Caesar Babcock enlisted in the local militia in 1775 in his master’s stead. He did the same in 1778 when the call came for more recruits. According to his pension application, “In the summer of that year was on the Island of Rhode Island where in an action with the enemy he saw a drummer by the name of Card killed by a shot in the breast while very near him.”[11] This action was likely during the Battle of Rhode Island on August 29, 1778 at Portsmouth.

In his pension application, Babcock stated that he had seen nearly a year-and-a-half of service, well past the six-month requirement to qualify for a pension. As there was little documentation however, his pension request was rejected. In response, two fellow soldiers from his old regiment wrote to testify that they had served with Caesar. The minister of the Baptist church in Newport wrote to vouch for the two men who had written in support, despite “Being aware that the statements of ‘negroes’ we sometimes regard with a degree of suspicion . . . .”

Caesar’s former mistress, Martha Babcock, wrote to the pension department:

Caesar was a slave to my said husband before the Revolutionary War and Caesar served as a soldier in the militia for my said husband and went to the Island of Rhode Island with the army commanded by General Sullivan to act against the British [meaning the Battle of Rhode Island in August 1778].[12]

None of these efforts could dissuade the pension committee. Caesar never received a pension or official recognition until his name was included on the monument at Patriots Park in Portsmouth, which celebrates the role of Black soldiers who served in the Revolutionary War.

Other enslaved men owned by the Babcock family who served in the First Rhode Island regiment included Primus Babcock, who enlisted in the regiment at the age of 38 and served for the remainder of the war. He returned to Hopkinton and used his skill as a cobbler to make a living.

The graves of these veterans, and other graves of black soldiers of the Revolutionary War, were mostly left unmarked and unadorned by wreaths. By the time of the marking of the Revolutionary War Graves by the Daughters of the American Revolution (D.A.R.) in 1890, many of the resting places of these slaves turned free servants and laborers had already been neglected for decades. Largely for that reason, a monument to the men of color who served in the American Revolution was erected in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, within the site of the Battle of Rhode Island in which the First Rhode Island Regiment was engaged in the field for the first time.

By contrast to these family slave lots nestled among Rhode Island’s rural areas, the loss of urban plots came early. With the destruction of houses for new development, any remains from adjacent servant or slave lots were removed and often deposited in the far flung corners of common burial grounds.

Newport’s Common Burying Ground on Farewell Avenue in Newport holds the largest number of African-American graves in the state. The city was a bustling commercial seaport during the colonial period, and many of the graves in “God’s Little Acre” as it is now known, are those men enslaved by Newport merchants, or those of the many who were brought Newport to work as apprentices in the shipbuilding industry, as carpenters, rope makers, furniture craftsmen, or stone masons.[13]

A significant number of the historical structures still standing in Newport, and in other cities that date from colonial times, were constructed in part, by these craftsman, both enslaved and free.

Providence’s North Burial Ground began as a common burying ground in the 1660s. It added the graves of indigent inhabitants to a corner of the land that had once been an indigenous burial site, but was still also used as a common for grazing cattle and sheep. This area was formally declared a burial ground in 1700, and opened to all citizens, from the prominent to the poor.

With the popular effort in the mid 1800’s to transform such burial grounds into landscaped parks, the North Burial Ground was transformed into a place of beauty for those who wished to be interred in such a setting. But the effort also marked the creation of the distinct separation between the wealthy, the middle-class, and the poor. For the latter, a “potters field” was created. It lies not just beyond those graves of more prominent citizens, but in fact, across a bridge traversing an abandoned stretch of canal on a thin strip of land below the lanes of a busy interstate highway.

Colonial era graves of some enslaved persons had been allowed to remain where they had been originally interred. In 1964, however, many others were removed to give the state a slice of the cemetery land through which the newly constructed I-95 would pass. The old stones were laid out face up, just outside the potter’s field. Here, lie the stones of Eve, the wife of Prince Cushing (1730-1780), Hannah Mar(s), who died a free woman in 1818; the small stone of two-year-old Primus Tillinghast (1748-1750), and the gravestone of Robert Millet, a former enslaved man from Fayetteville, N.C. who died in Providence on September 4, 1823. Some thirty-eight other stones also lie exposed to the elements. A large granite monument acknowledges their removal from the cemetery grounds, but contains none of the names of those carved on the disintegrating stones.

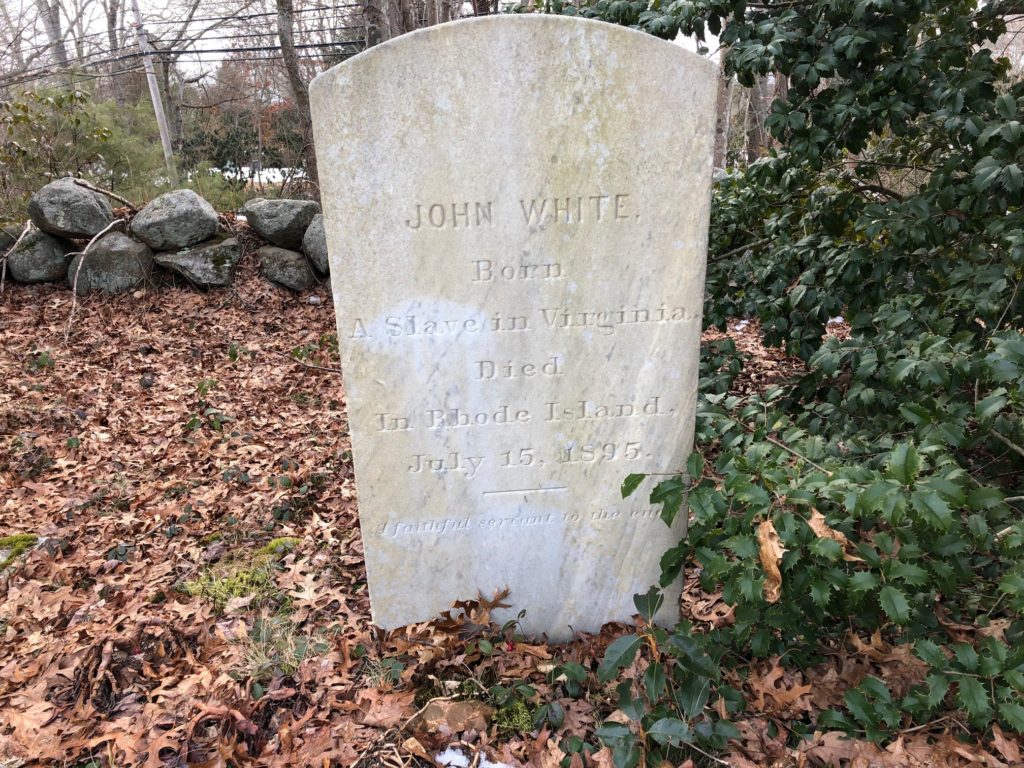

On occasion, a long-standing black person in the community would be recognized with a headstone in the village cemetery. One such person was John White, who was a slave in pre-Civil War Virginia. After he was emancipated, likely after the close of the Civil War, he left the South and settled in the black community of Kingston, Rhode Island, where he became a fixture, working in the local marble shop, and often reflecting on the days before he gained his freedom. His tombstone is in the southwest corner of the Old Fernwood Cemetery, long associated with the Kingston Congregational Church. It reads simply, “Born a Slave in Virginia Died in Rhode Island July 15, 1895.”[14] It is likely that white admirers paid for the stone and decided on its wording.

Gravestone for John White, “Born a Slave in Virginia, Died in Rhode Island, July 15, 1895, A Faithful Servant to the End.” Old Fernwood Cemetery, Kingston (Christian McBurney)

Two gravestones of domestic enslaved persons from that time period remain in the Newman Cemetery in East Providence. A cemetery long associated with the Newman Congregational Church, around which it lays, the burial ground is one of the oldest in the state. Because it is in an area that was once part of Rehoboth, many of that town’s earliest residents are interred in the older part of the cemetery.

The graves of two enslaved persons lie close to each other, even though each was owned by a separate family. Other enslaved and “colored” graves were likely once nearby. I discovered one, the gravestone of Anna Bowen, a long-lived enslaved woman of Colonel Jabez Bowen whose inscription reads: “Thou was a good master, I was a good slave. I now rest from my labor and sleep in my grave.”

Anna Bowen died at the age of eighty. Faithfulness and longevity seemed to have counted a great deal as to whether or not a household enslaved person was recognized with a memorial marker.

Just a few feet away lies another grave of a domestic enslaved person who had been the property of John Hunt, another prominent citizen of East Providence. Hunt had established the early Hunt Mill along the Ten Mile River as it snaked through the town.

Perhaps the most remarkable remembrance in stone of a domestic enslaved person or servant in the state can be found in the elegant Swan Point Cemetery of Providence. Lying on the side of a hill that holds an elegant memorial is a narrow slate stone from an earlier era, on which is carved:

Walker, a native of the Sandwich Islands

brought from Owhu by B.D. Jones in August 1804,

died in 1814, being about 18 years

He was a faithful and affectionate servant

Walker was a native of the Hawaiian islands. It appears, but is not certain, that Walker was enslaved. If true, this means that despite Rhode Island’s ban on the importation of enslaved individuals, Jones, like other merchants and slave traders of the period, found ways to circumnavigate the law. A successful merchant with at least one vessel at his disposal, Jones may have registered his young enslaved child as a “cabin boy” for the journey back to Providence, but once here he became a “house boy” or personal servant at the merchant’s home.

This episode also illustrates that at times, an involuntary servant was viewed with affection by the white family who owned the servant. Walker was the exception from most family slaves, for his stone, if not his remains, were moved with the family plot nearly thirty years after his death. It is one of the few memorials to an enslaved person (assuming he was enslaved) that was not left behind to be forgotten.

Notes:

[1] No George Coggeshall appears in Newport or Washington County in the Rhode Island census of 1774, so we may assume that George was one of the enslaved persons held by the white Coggeshall family of Newport. The census for Newport showed Nathanial Coggeshall having nine persons of color in his household; Billings Coggeshall, six; James Coggeshall, three; and Elisha Coggeshall, three. It is probably the case that most of the persons of color, George Coggeshall among them, were enslaved. See 1774 Census of the Inhabitants of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, http://newhorizons, R.genalogicalservices.com/1774-ri-colonial-census.htm [2] Hazard, Caroline, ed., Nailer Tom’s Diary otherwise The Journal of Thomas B. Hazard of Kingstown, Rhode Island 1778-1840 (Boston, MA,: The Merrymount Press, 1930), p. 3. [3] Knoblock, Glenn A., African American Historic Burial Grounds and Gravesites of New England (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2016) p. 65. [4] Ibid. p. 69. [5] See Geake, Robert A. A Cocumscussoc Reader (2017), p. 22. [6] A popular 1992 guide to graveyards of the town makes no mention of any existing or lost slave lots. Mention by Fitts, in his research for his 1995 thesis on the Narragansett Planters at Brown University, seems to be the first mention of the burial ground at Cocumscussoc since Harris’s recording. Later publication of “Captive at Cocumscussoc” by former Cocumscussoc Association president Neil Dunay in 2016, provided a map and updated information about the site, as did this author in “A Cocumscussoc Reader” in 2017, in which several excerpts from Harriet Smith’s journal describing the site were published. [7] Quoted in Rhode Island Genealogical Society, “North Kingstown Historical Cemeteries,” p. 179. [8] Geake, Robert and Lorén Spears, From Slaves to Soldiers: The 1st Rhode Island Regiment in the American Revolution (Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2016), pp. 118-20. [9] Hopkington, R.I., Town Probate Records, TC 2:156. [10] Grundset, Eric ed., Forgotten Patriots: African American and American Indian Patriots in the Revolutionary War (Washington, D.C.: National Society Daughters of the American Revolution, 2008), p. 215. [11] Caesar Babcock Revolutionary War Pension Application, RI, No. 339, National Archives. [12] Crowder, Jack Daniel, African Americans and American Indians in the Revolutionary War (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co. 2019), pp. 16-17. [13] Preservation Society of Newport, “God’s Little Acre”, online at http://newportmansions.org [14] McBurney, Christian M., A History of Kingston, R.I., 1700-1900 (Kingston, RI: Pettaquamscutt Historical Society, 2004), pp. 279 and 358.