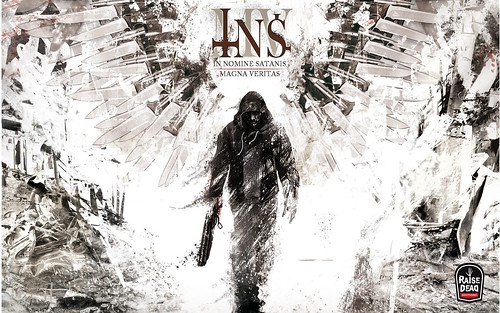

IN SHORT… INS / MV was a bit of an iconic game for me. I “missed” it in the 90s when I started playing and was largely consumed by other games. I recently discovered that a 5th edition, with a lighter setting and ruleset than prior editions, had been published in 2015. I decided to try it out as a one-shot with a few folks (with whom I regularly play). The challenge was to convey the key points of the setting from on a French-only core book and rules to a group of non-French-speaking players… But we managed! It resulted in a pretty fun game, action driven and cinematic.

# # #

THE MEDIUM

We ended up running a 4-hour game, with 4 players — 3 of which I had played with multiple times. Voice on Discord. VTT on Let’s role.

THE BACKGROUND

I had typed up a quick summary of the setting, to seed the general ideal for the players.

Things used to be simple in the times of the Great Game. Heavens vs. Hell. God vs. Satan. Angels vs. Demons.

We had structure. Orders would come from above, and we would carry them on. Usually, it would entail destroying each other on Earth. But not always. Sometimes, things were not subtle. Like “Project 0” – releasing a global virus to wipe humanity back to its population of Anno 0. I’m not sure which side sponsored this… Sometimes, they were more subtle. Like “Project pope-in-the-hole” – saving the future pope from falling into a manhole while visiting New York. Again, not sure if it was us or them.

There were rules. Don’t let yourself be caught by humans, or clean up the mess. Serve your Lord. Obey the hierarchy. Don’t expose the Great Game to humans. Evangelize your creed. Destroy your enemies. We had a boss, and there was no messing around. We had to carry out the orders…

There were affinities though. I was a demon. My boss was Vapula. Scary dude. We were into the tech side of things. I wasn’t there when he nudged the guy who invented the gunpowder. But I was the guardian demon of Mark Zuckerberg during his time at Harvard. Good guy. Love what he has done.

A few years ago, everything changed. There must have been a reboot of the systems. All of us, angels and demons alike, lost our connection to the hierarchy. More annoyingly we lost our awareness as angels and demons, and started living a lull inside our human physical incarnation. Little by little, we reclaimed our true nature and regained some of our memories and powers. We found a few of our own and formed groups. There are rumors of some of the old bosses making contact. In the meantime, we do what we can to advance our agenda. And we try to avoid raising attention – demons, angels or humans, some exterminators are aware of what we are, and when we step outside the lines, destruction rains on us…

The worst thing is : we no longer know for sure that we go back home when we die on Earth…

We are the lost generation of Heavens and Hell.

THE FICTION

The characters were quickly done, and yet quite diverse and interesting. An angel using his wealth to fight the Devil, while enjoying the finer things money can buy on Earth. A janitor treating all animals on Earth — humans and cockroaches alike — as creatures of God to protect. A psychiatric nurse using his profession and access to mental institutions to find demons to exercise. And a military officer hunting down them more aggressively, one bullet at a time.

I ran a published scenario of INS / MV 5th edition : “La ruée vers l’ordure” — a pun on the gold rush being a garbage rush. In short, the players had to stop the inauguration of a chemical factory whose director, a demon, had plans to unload toxic waste through the water system of a small city. Further, the demons had managed to set suspicions on two powerful angels, on site for different reasons, and get them to attack each other, with the group of players in the middle, as diversion

The story was very investigative in nature, with a 1h infiltration and final fight scene at the factory at the end, and an epilogue hinting to a higher order villain in the background.

ONE SCENE

What I think was a very INS / MV scene occurred when the group had to defuse the tension between the two powerful angels, going at each other throat. (The players, at that point, wrongly suspected both of them to be demons.) A powerful angel punched a player’s character through the wall in a very comic-like cinematic scene, before the police arrived to arrest folks and pick up the broken body of the character (who was already starting to regenerate).

THE SYSTEM

The INS / MV 5E system is quite intuitive. Roll 3d6 and count success against the characteristic level for 1, 2 or 3 successes. (111 is God’s intervention and 666 is Satan’s, but unfortunately neither occurred.) I did have to make, on the fly, some rules for group and extended rolls, which weren’t specified in the core rule. I always find it a bit odd when these very typical resolution problems are not explicitly addressed in the core book.

6 responses to “In nomine satanis / magna veritas”

Hi Denis, and welcome! This is a great post, and I hope some of the other francophone participants here can add their thoughts. The game has been mentioned in some seminars, and I’m often irritated that my only direct knowledge comes from the American re-design called In Nomine. It retains the “d666” resolution, so at least I know about that.

Which leads to my specific interest in commenting. One of my best routes to understanding play is failed resolution: how often, and what happens. Did anything outright fail during play (no successes), and if so, what happened? I.e., how did the circumstances and situation change?

I don’t have a specific point or insight in mind, only to form a better vision of the play-experience.

Thanks Ron for the read and the great question. I totally agree with you that failure resolution is always a very telling part of the resolution system. When I do a one-shot of a new game, I try to run the “rules as written” to test the designer’s intent. In this case, I noticed three things. 1/ No mention of a “golden rule”. 2/ A very prescriptive mention of why there are no opposition rolls. 3/ No mention that a failure is not a failure. So I took it just as that : when you fail, you just don’t succeed, and there is no encouraged flexibility in the system. (My two twists described in the original post were more “accelerations” of multiple rolls than mechanical changes.)

We had two significant fails. (Along with minor ones, or combat “you miss” ones.) First, on an investigative roll (reading the mind of an NPC in a coma) – and I didn’t give actionable clues, but instead a brief description of the atmosphere and general setting of the attack the NPC had suffered, which added color. Second, on a negotiation roll (trying to convince the police not to arrest PCs and their allies after a mess) – and this resulted in losing a powerful ally (who went to prison for the night), forcing a PC to find a way to escape custody, and overall forcing the group to be clever about their final approach.

What’s very interesting in your question as I think more about it is the following. I think I have got complacent with the PbtA / FitD “succeed at a cost” as my default way to handle failure. However, maybe I should curb this habit. This play had plenty of “no success failures”, and the walls didn’t crumble… In fact, it can be more interesting to handle failure as a non-success. The (worthy) challenge for the GM in these situations is to help “turn a roll failure into a narrative success”. And sometimes it’s not easy, and it ends up with an awkward “you slip on a banana peel as you run after the goblin” and some eye rolls, and that’s life…

Curious about your thoughts on this topic if you have documented it somewhere already.

It’s a big topic! An early or preliminary post was Monday Lab: Roll to know, and the primary or origin-post is Monday Lab: Whoops. Some follow-ups include Monday Lab: Probable cause, No easy task, and We both fail. The concept as developed in these posts, and various discussions along the way, is now applied across a lot of the coursework too.

I don’t want to launch into a big lecture, especially since you’re evidently putting a lot of the pieces together on your own, in even just one reply. So, briefly, to stay specific to your post, the key function (if that’s the right word) that’s revealed is to shape the problems and context for the next “wave” of play. If characters don’t know a certain thing, then their actions and attention take place without it, as well as various other entities’ actions and attention being enabled or negatively affected due to the same thing.

Here the conversation breaks down into abstractions because I wasn’t at the table and don’t know the fiction at hand in any meaningful way. It’s not a difficult concept, though. If “Bob” doesn’t know that “the deal goes down at midnight,” then the deal may well indeed go down at midnight, and subsequent play occurs in the context of that deal having been completed, which, for Bob or someone Bob cares about, may well be a terrible new context.

Here’s the important bit, though. Whether a failed “roll to know” (or whatever resolution by any means) is deemed genuinely to shape the circumstances of subsequent play, or, alternately, that play must halt and wiggle about to get back into the “right shape,” i.e., the circumstances which someone deems appropriate for play to continue. One version of wiggling in this way is to soften or basically ignore the failure as such; another is to concoct various opportunities or circumstances that turn it into a mere delay or detour; and of course, the blunt instrument of simply lying and saying it didn’t happen (“ignoring the dice for the sake of ‘fun’/’the story,’” et cetera).

A huge sector of role-playing culture and especially publishing took that second path in the very late 1980s, which is the origin of such stupidities as “roll vs. role” and the unique, genuinely nauseating distortions of the word “story” that we continue to live with today.

I did say “briefly,” didn’t I … anyway, even the instance you’re talking about here, especially the failed negotiation roll, shows your awareness of this issue during play. I can’t say, and I really don’t want to pry, whether the loss of the ally turned into a real shaper of circumstances, “do not pass Go” as it were, or into a swerve that deviated from your comfort zone for what would and should happen and was brought back there eventually. This isn’t an interrogation. What matters is the chance to isolate the topic and to reflect on it, when and how you want.

Super interesting question, Ron.

So, having watched the first video (and will go through the others), reflecting upon these two rolls and your question. I think the answer is that I turned the roll failure into a success from a narrative point of view, but not a fiction point of view… And it didn’t hit me until now.

In the first instance, I set the difficult high from the beginning because I *sort of* didn’t want the player to succeed in the first place (although I was justified by the rules to do so). It would have open a very accelerated path to the end villain quickly, and changed the storyline quite a bit. And thinking back about it, it would have been a *great* and fun idea… I just got cold feet about managing it. In the second instance, reality is that I adjusted down the combat difficulty taking into account their powerful ally wouldn’t be there, instead of letting them run and solve the challenge of being overwhelmed by the opposition, now that they had lost a precious ally.

So I did manage to turn the failure into a cogent narrative *sequitur* that didn’t look like a bump in the road to the players. But I did miss an opportunity to let the fiction develop truly based on the decisions of the players. Even though they didn’t know it or see it. (In this case, I didn’t have the issue of meta-knowledge.)

That raises an interesting question, using a funny analogy: if a magician’s sleight of hand is so perfect that nobody can see, is the magician performing “real magic”? Probably not…!

Or in RPG terms: if the GM’s narrative skills are so smooth that nobody can see the patches in the storyline, even with failed rolls, is the GM really producing “fiction”? Probably not either… Not in the way we aspire to in a social game.

Except that I don’t believe in magic. But I do “believe in fiction”! And these moments in a game where it’s being woven at the table in some sort of fun state of grace by everyone. And thinking (probably too deeply about it), these may have been missed opportunities here I’m talking about.

In any event. Very fun questions. And looking forward to spending some time with the videos I haven’t watched yet.

I may contribute with some context about the game and play culture around.

INS/MV is an unavoidable game for any french speaker who played rpg without being totally isolated from a community of roleplayers during the 90s. I was introduced to it that time, when the 3rd edition got out, with very few modification through the editions except for the last one (the 5th), which is described here.

The French version has a very different feeling that the american one – it’s a humorous social commentary in the vibes of Pratchett and Geiman “Good Omens”, or something like the “Paranoïa” RPG. Every archangel has a humorous quote, such as Haagenti, demon prince of gluttony, “They should eat journalists during starvation crisis in third world countries, there are plenty of them there during these times.”

It was generally played as casual one-shots, like “hey let’s do something fun tonight insted of playing Warhammer, yeah let’s play INS/MV” (note the european vibe of that typical sentence).

The game itself is clearly a product of its time – preplanned outcomes, basically books of fun descriptions of the history of relationships between archangels and demon princes, a long arc / metaplot. As an example, the fourth edition 2 tome scampaign “Fire & Ice”, where the characters will be caught in the war between two twin demon princes, cannot be fully understood if you haven’t played or read the various 2nd and 3rd edition “adventures”. It fits into the Vampire the Masquerade problems of being novels or super railroady scenarios.

This edition is a bit different. It wasn’t meant to be published. It’s basically the edition that the original creator of the game, Croc, was playing with his own table. Some of his friend convinced him to publish it as it is. So the corebook is mainly a product of play. I haven’t played it myself but I played the various edition before, casually, and tried to GM the 4th edition but stopped before it came out.

I’ve read a lot of the modules for the various previous edition of that game, and it’s clearly presented as a sequence of scene to pass through, with a predefined outcome to bring on. Despite of this, I remember that the notion of “failure” was clearly on the table in the play culture I’ve been in contact with. It actually happened a lot of times: failing the mission. Once it happened, and depending on how the group would handle this, you could have “business as usual” with hindrances (“you’ve fucked up the mission so you have a dick in your forehead for that one”), or it would open up play, with the next scenario taking the failure in account.

I’ve never seen the game being played without the use of a published adventure, though.

I remember an interesting property of the 111 or 666. If you were an angel, getting a 111 was good – you have a divine intervention – and getting a 666 is bad, Satan himself interfere. If you were a demon, it was the opposite (playing demon was super rare, everyone one played angel, mainly because angels were meaner than demons. The Skinhead gang worshiping Archangel Laurent being a classical trope). Getting of this number is basically, by the rules, introducing a Deus Ex Machina. Some GM treated this in the humorous style that comes with the game “So you’re chasing that demon in this extra small unknown city of La Bourboule and you fall into the pool of that house … just in front of God who is drinking a Mojito”. But some of them treated it as a “it was just all part of the Big Game” – the Big Game is the setting being God and Satan’s war (in fact a game they play so God doesn’t get bored of life). And those results could radically change the situation. You were doing a trivial thing, but now it was part of God’s plan, and the GM makes a new situation from that.

Thanks for this. I did know 5th edition was quite different from the rest. But I really enjoyed reading your account of the “color” of INS / MV of the mainstream editions at the table. I sort of wish I had played it back then…