Last year in the run-up to the big Celts exhibition at the British Museum, project curator Rosie Weetch blew my mind open with the following discovery:

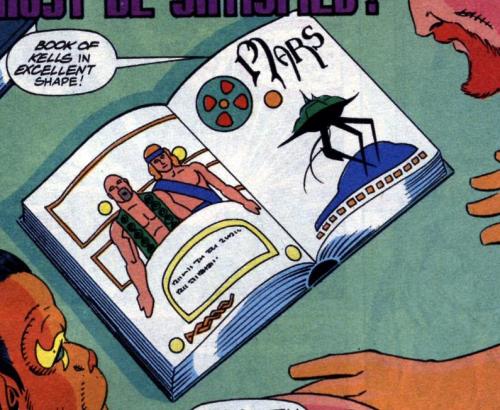

With this foresight we can now protect the Book of Kells during the second invasion from Mars. Thanks Marvel Comics! pic.twitter.com/Dxj5ERzijQ

— Rosie Weetch (@rosieweetch)July 22, 2015

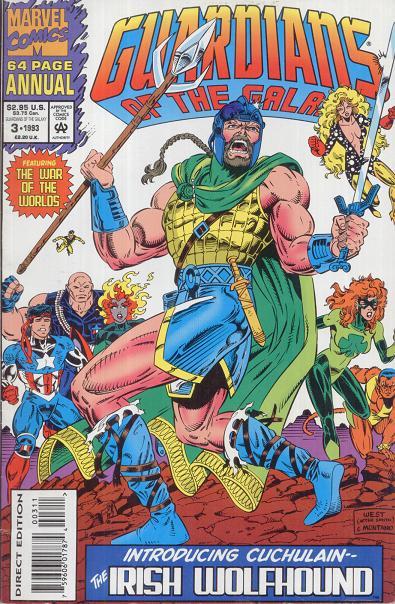

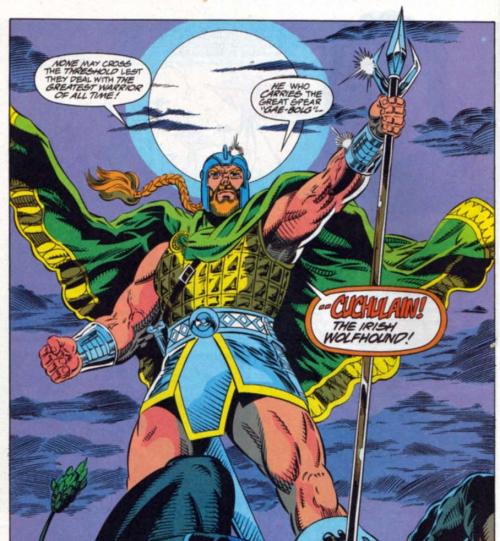

This is a page from the Guardians of the Galaxy Annual vol. 1 #3 (1993) which introduced a new old character into the Marvel Universe: Cuchulain, AKA Cú Chulainn, Hound of Culann, hero of the 8th-century Táin Bó Cuailnge and protagonist of the Ulster Cycle of early Irish mythology. I was lucky enough to be sent a copy by my friend and pop culture archaeologist Mark Hall, and I will proceed to nerd out about it here.

Marvel have never shied away from appropriating mythological figures and gods into their comics, and Cú Chulainn is a great fit, as his character is known from the (effectively serialised) early Irish literature. He is one of the original action heroes, trained in martial arts on the Isle of Skye in the Fortress of Shadows by the badass warrior queen Scáthach (you can’t make this stuff up). There are several more recent comic book adaptations of this figure; it is fairly begging to be made into a film.

But GotG’s Cuchulain is rather less exciting. He never becomes a major character, appearing only in four issues in 1993-94. His character page on the Marvel Database is brief, and includes the rather laconic view that “Cuchulain’s only limitation is his ignorance of the 31st century as he’s spent all his time in Ireland’s fields.”

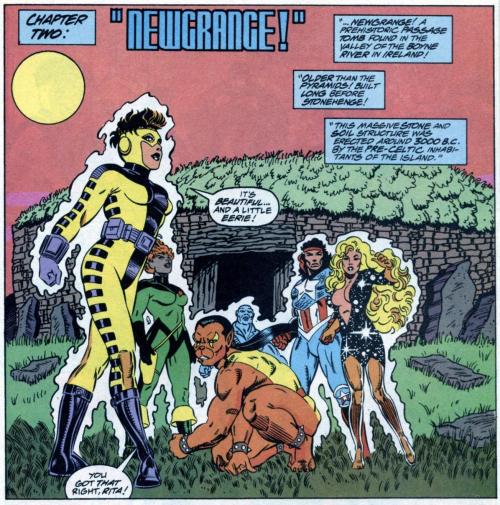

But his debut appearance is worth some archaeological consideration: despite taking place in the distant future, it manages to combine the Book of Kells, the passage tomb of Newgrange and Captain America’s shield. This is so incredible I hardly know where to start.

So let’s start by taking this seriously.

Playing with time in the Marvel Universe

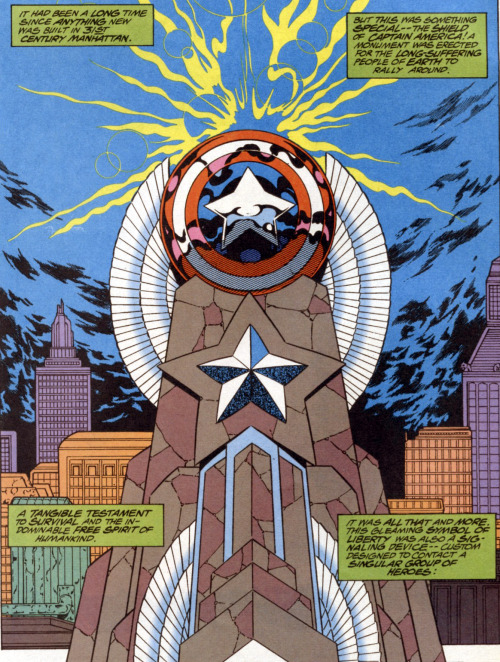

The comic opens with a vision of 31st-century Manhattan. We see a new monument incorporating the shield of Captain America, by then a precious relic more than a thousand years old. The monument takes the form of a sort of pedestalled cairn, combining futuristic geometric forms with the generically ancient yet vaguely Celtic grammar of erecting a commemorative pile of stones. I was pleased to learn that this is just one of many appearances of Cap’s shield through time: the artefact apparently has a long afterlife throughout the Marvel Universe. Here, it stands for an intangible Americanness bound up in high-minded notions of liberty and justice, but ironically in a martial, weaponised form. In this particular future, it is being used to inspire a benighted human race laid low by a Martian invasion a thousand years earlier. I do love a good Dark Age story.

The plot (such as it is) revolves around a quest to find the 9th-century Book of Kells, the famous illuminated manuscript produced on Iona and masterpiece of Insular art. However, like any sci-fi macguffin, its importance to the story is vague at best. The Guardians are summoned by the president of the United States to find the lost manuscript in order to inspire people to read again (?).Years before the cult film Idiocracy, the story is framed with a future America in which there is 90% illiteracy caused by addiction to something called Realitee-vee. We learn later on that this is a TV broadcast that comes with an addictive mind-altering gas, developed by (of course) Doctor Doom. While this can hardly be called prophetic, it is hard to resist the fortuitous resemblance to the phrase ‘reality TV’ which would become a staple of low culture in the late 90s with shows like Survivor and Big Brother. The clouds were already gathering though: the first season of MTV’s The Real World aired in 1992. DOOOOM! [shakes fist]

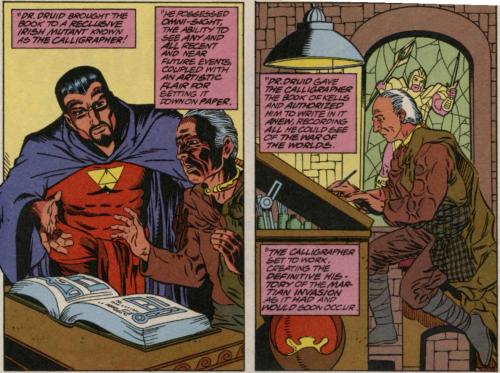

Back to the Book of Kells. We are told that when the United States fell to a Martian invasion in the 20th century, a retired Avenger called Doctor Druid decided to steal the Book from Trinity College for safekeeping. Unfortunately, instead of protecting the priceless artefact, Doctor Druid employed a psychic called The Calligrapher to ‘update’ the manuscript with the story of the Martian invasion. Never mind that it is a gospel book, so it’d be quite a strange update, following the Gospel of John with a Martian attack.

Said Calligrapher is a walking mishmash of Celticity, wearing a Highlander’s great kilt and an Iron Age gold torc, illuminating manuscripts before a stained glass image of Cuchulain. He exists for all of three frames before being inevitably killed by Martians, but not before secreting the Book of Kells away and (as we soon find out) mailing a clue to the New York City Public Library (odd, since it was presumably levelled along with the rest of America by this point).

Handily, in the 31st century the American government has a ‘Literary Corps’ who have been busy excavating the site of the old NYC Library where they found a single leaf of paper (just the one?) which happens to be the very clue left by The Calligrapher. It is a drawing of three spirals, which our hero Major Victory, in his role as ‘team historian’, connects with the megalithic art on the entrance stone of the Neolithic passage tomb at Newgrange in Ireland, and so off they go.

So far, the story has a lot to offer archaeologists, from the long biography of Captain America’s shield to the ethical conundrum of preserving antiquities like the Book of Kells in wartime. There is even an excavation, sadly not depicted. And while the figure of the Calligrapher is hopelessly anachronistic, one could equally argue that he is an embodiment of the non-linearity of time, a liminal figure who stands above and outside of chronology. Only such a shamanic figure would be allowed to update/vandalise the Book of Kells in this way. The story is playing with time, merging real-world artefacts with the modern mythologies of the Marvel Universe, using archaeology as a mediating trope to fuse them. The timeplay only ramps up once the setting changes to an actual archaeological site.

Enter the Wolfhound

The Guardians now head to Newgrange and are immediately impressed by the Neolithic tomb’s ‘overpowering spirituality.’ They try to walk into the passage tomb to claim the Book of Kells hidden within, but are instead assaulted by ‘the greatest warrior of all time…Cuchulain! The Irish Wolfhound!’

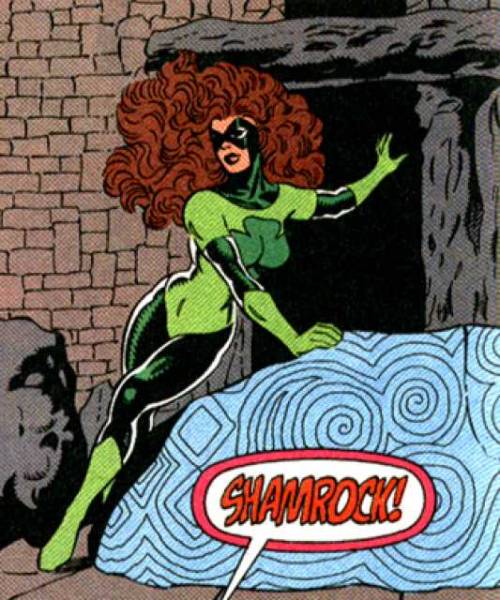

Hijinx ensue in which the Guardians unleash several politically incorrect slurs against the legendary Irish warrior as they try and punch their way past him. The fight is only stopped by the arrival of two more superheroes, a Michael McDonald lookalike called Hollywood, and a curvy Irish lass named Shamrock because it had presumably been a late night in the writers’ room and they were tired. In an image I’ll have to fit into an archaeology lecture someday, Shamrock is introduced slinking around the famous Newgrange entrance stone.

After several pages of punching, all the characters now kiss and make up long enough to get some badly-needed exposition. Turns out Shamrock’s backstory is dark as fuck, involving the Irish War of Independence, kidnapping and patricide. Her powers – the ability to influence luck in her favour, because again the writers got their knowledge of Irish people from the back of a Lucky Charms box – are based in a dark secret. At some point in her already troubled childhood, Shamrock’s body became a repository for the troubled souls of all those who have died in war. She used her luck-powers to become a superhero, but never really stuck with it, probably because using her powers involved calling forth the restless dead spirits that haunt her every move.

As if that weren’t torture enough, during the Martian invasion she was informed by Doctor Druid that the poltergeists she hosts will also cause her to live forever, in what sounds like a living hell. But this made her a useful patsy, and at this point Doctor Druid passed off his stolen goods to her by appointing her the new guardian of the Book of Kells. To help assuage the crushing loneliness of immortality while inhabited by countless troubled spirits and hiding out in an empty Neolithic tomb, the Druid’s last act was to incarnate one of these ghosts to be her eternal companion: none other than the hero Cuchulain. I need a stiff drink.

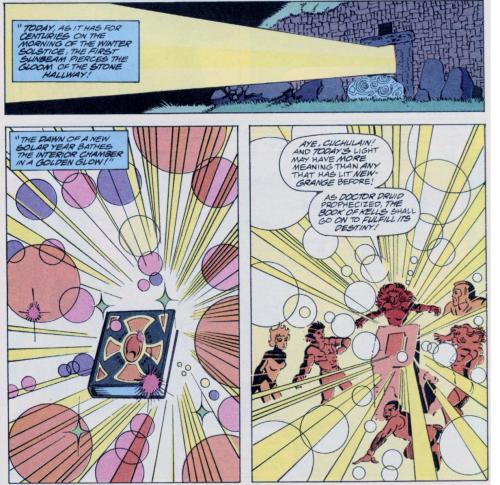

Thankfully, the mood is rather lightened by the arrival by a demon called Samhain, who wants to destroy the book for its ‘biblical propaganda’ and inexplicably chose the moment in which there are no fewer than nine superheroes in attendance to strike. Of course, he is dutifully cast out by Shamrock, but not before we get a glimpse at the stone altar in the heart of Newgrange where the Book of Kells is kept.

Then the winter solstice shines on the book, signalling a new hope for humankind after a thousand year Dark Age. With little ceremony, Shamrock casually hands Major Victory the priceless manuscript and walks off into the sunset with Cuchulain. They intend to ‘follow in the footsteps of [their] Celtic ancestors …and attempt to reintroduce civilisation.’ Cuchulain, who has taken a serious backseat in the third act, would return for another three issues of GotG where he gets to do some more punching and sleep with Yellowjacket.

Newgrange and Kells as pop culture archaeology

There is no defending this comic; more time was spent meticulously drawing the contours of our heroes’ asses and boobs than justifying the need for this holiday to Ireland. Yet a good few pages are devoted to introducing the Book of Kells and its biography down to its current display at Trinity College. The comic also manages to fold in several salient aspects of Newgrange, though they are rather incidental to the action going on around them: the megalithic art, the tomb’s alignment on the winter solstice and its legendary connection to Cú Chulainn. This story is an artefact in its own right, a testament to the reach of at least a basic understanding of archaeological matters. It’s like the stories of Newgrange and Kells rang out from the ancient past, and this comic is just one distant echo.

It hardly matters how much they get right or wrong; it is more important to note the Marvelisation of Irish heritage. Both Newgrange and the Book of Kells are huge money-spinners, heavily marketed as tourist attractions and with a wealth of pop culture re-imaginings to their name; The Secret of Kells might be the best early medieval movie ever made. A more recent example is the Star-Warsification of Skellig Michael; our most enchanting modern myths are given their resonance by successfully incorporating elements of the ancient past. In short, there are some archaeological artefacts and monuments which become so iconic that there is no longer any point in policing their interpretation, as we spend our careers making them accessible to inspire just such imaginings. They are archaeology as pop culture, and each iteration in movies, novels and comics reaffirms their place in the public imagination.

The comic also attempts some archaeology of its own, imagining the future histories of contemporary events and the artefacts that bear them witness. In this universe, artefacts do have the agency that archaeologists like to ascribe to things. In some ways, Marvel is busy building its own mythological cosmos by reflecting on the way real-world objects and places like Kells and Newgrange intrude into the present.

It may be playful, but as Cornelius Holtorf has pointed out, playing (in) the past can be as meaningful as subjecting it to scientific analysis. If for no other reason, timeplay like this is how new archaeologists are made. We all have a pop culture origin story; I certainly never recovered from reading Tolkien at a young age. Surely this comic didn’t give rise to a generation of Celticists, but it is surprisingly fun to play in this world for a while.

Larger versions of all images available here

Follow us on @AlmostArch

Notes

eluneth liked this

eluneth liked this jericho-b liked this

devilsurvivor2 liked this

devilsurvivor2 liked this jash-snash liked this

pastafangirl liked this

bigkingkahuna liked this

ceallach-declare liked this

stardustsgalaxies liked this

say0chan liked this

king-of-zeroes liked this

dogecream-sundae liked this

tainbocuailnge reblogged this from derpcakes

lunasilverhart reblogged this from derpcakes

lunasilverhart liked this

ritsufan777 liked this

kurozu501 liked this

kurozu501 liked this joshnekuu liked this

derpcakes reblogged this from almostarchaeology

derpcakes reblogged this from almostarchaeology  derpcakes liked this

derpcakes liked this gaebulga liked this

almostarchaeology posted this