The Illustrated Press

Until the 1850s, newspapers featured few images. In the eighteenth century there might be a small woodcut here to signify an incoming ship or runaway slave, another there accompanying a property for sale, but nothing directly related to news events. Into the first decades of the nineteenth century, the banner at the top of the front page was usually the most elaborate—if not the only—illustration in a newspaper. And as printers shifted to faster revolving presses in those early decades of the century, they actually used even fewer images than they had in years past.

During the 1830s and 1840s, some American daily penny newspapers began to occasionally include wood engravings related to news events, particularly the New York Herald, which, in 1845, printed the first-ever full-page pictorial cover in a daily newspaper when it covered Andrew Jackson’s funeral procession. But by 1850 it, too, realized that the wood engraving process was too lengthy and expensive to make profitable and ceased to include images. (Lithography was a cheaper and quicker image process, but it could not be produced on the same press as handset movable type.)

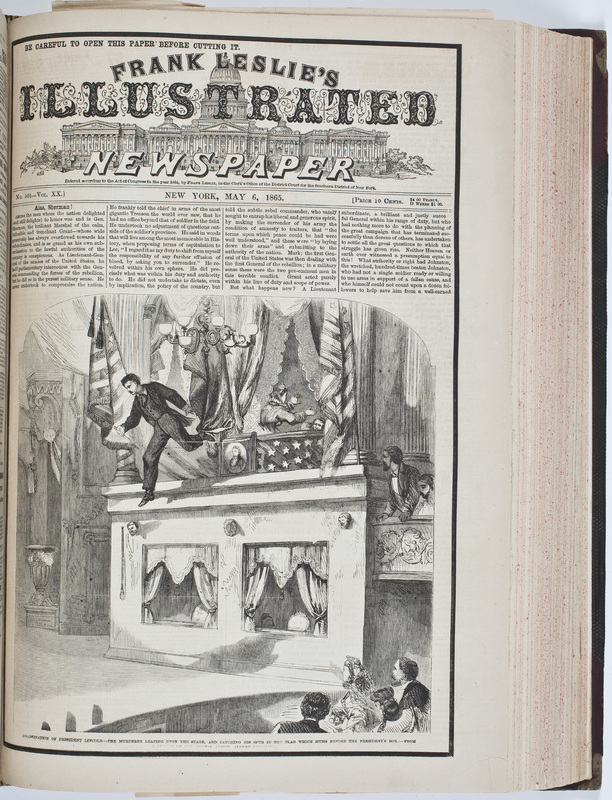

In the early 1850s, a handful of American illustrated newspapers cropped up, but due to a combination of economic and technical production difficulties, they either barely survived or folded altogether. The engravers weren’t skilled enough or fast enough, the production was too costly, and by the time the finished blocks made it to press, their subject matter was no longer news. It was not until 1855, when an English immigrant named Henry Carter (alias Frank Leslie) began his own illustrated newspaper, that the United States saw its first commercial success in the illustrated press arena. Developments in transportation, printing technology, and the literary and pictorial market, as well as Leslie’s six years of experience in the engraving department at the London Illustrated News, all combined to make Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper a success. Still, these factors alone were not enough. Instability remained the norm for the first few years until the debate over slavery and the commencement of the Civil War solidified the desire and need for an illustrated press to satisfy an expanded middle class hungry for news and knowledge.

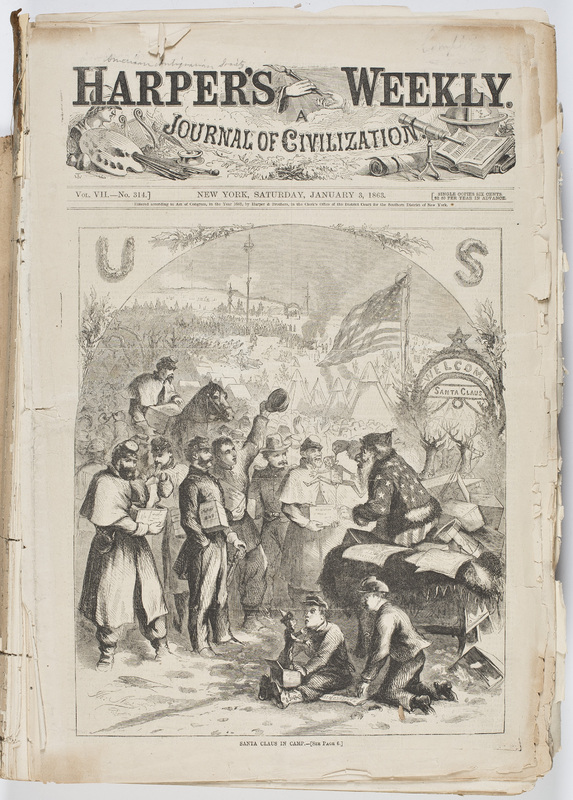

"Santa Claus in Camp," from Harper's Weekly, January 3, 1863. Harper’s Weekly became such a mainstay of popular news culture during the Civil War, that the newspaper could make references to its own popularity within its illustrations. Copies of Harper’s are among the presents Santa Claus is handing out to the war-weary soldiers stuck in camp for Christmas.

By the start of the Civil War, other illustrated weeklies had also joined the field, Harper’s Weekly chief among them. When the genteel Harper Brothers firm established Harper’s Weekly in 1857, it attempted to retain its respectable reputation, staying above the fray and above reproach, focusing more on literature for a broad reading public than news. Frank Leslie’s, in contrast, purposely focused on news events and topics appealing to a wider, more varied, and often less-genteel audience.

Though during the antebellum years Leslie’s tried to cover events in a nonpartisan way and Harper’s attempted to avoid controversial topics altogether, neither newspaper could ignore the mounting sectional crisis. Despite worries about losing Southern readership, after the conflict began both papers switched to a strong pro-Union stance and found a wider audience in a Northern populace now invested in war. Throughout the war, Leslie’s and Harper’s, as well as the New York Illustrated News, became staples for a Northern public eager for news and ways to visualize the conflict. They were also a lifeline to soldiers, who had a lot of downtime in camp and were always looking for reading material. The weeklies provided entertainment as well as news. Some soldiers subscribed to the illustrated papers and others received copies distributed by the United States Sanitary Commission, but most bought them at a marked-up price directly from newsagents who followed the troops.

Unlike photography, which, due to its long exposure time and difficult development process could not capture action or spread new images widely and quickly, the pictorial press was able to deliver images of an event into people’s homes within a week. This was made possible by dispatching special artists—a small and particularly dashing subset of the “bohemian brigade”—to follow the armies and sketch battles, encampments, and other events of interest. They would send sketches back to the papers, which then had draftsmen and engravers turn the sketches into woodblock engravings for printing. Improved methods of completing the wood engravings, including breaking large engravings into small blocks so that multiple artists could work on the same illustration simultaneously, also helped to expedite the process.

In the South, the state of the illustrated press was vastly different. Before hostilities began, the New York weeklies held a wide Southern readership. After the start of the war, the South was cut off from Northern publications, just as it was from an array of other commodities. To fill this void, and to offer a Southern perspective on the war, the Richmond publishing firm of Ayers and Wade established the Southern Illustrated News in 1862. Though it managed to last for two years, it was in fact barely illustrated, featuring only one or two illustrations an issue, and it was perpetually plagued by a shortage of paper, ink, presses, and above all, engravers.

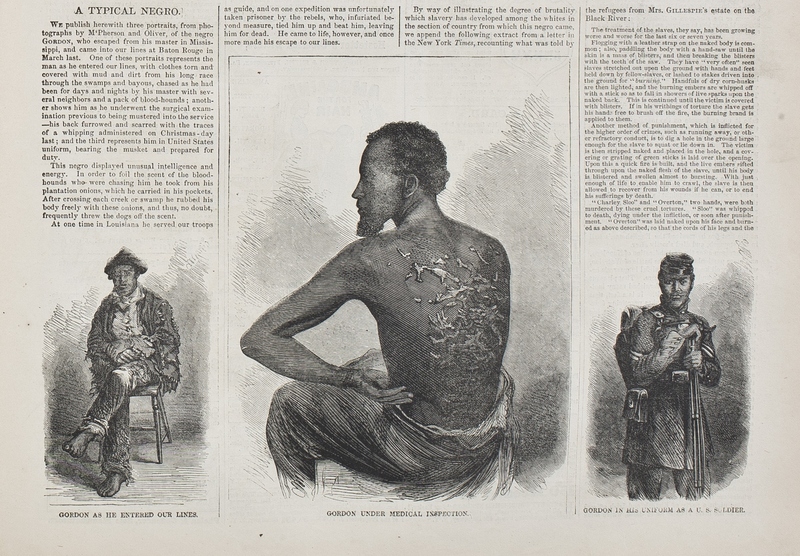

Nonetheless, some copies of Northern illustrated papers did manage to reach the South. In some cases, the Southern papers chose to respond to specific articles published in the Northern press, such as in the case of “A Typical Negro,” which the Southern press found particularly inaccurate and offensive.

The reaction to this article also speaks to the ways in which the Northern press’s depictions of African Americans changed over the course of the war. Though in the antebellum years the papers tried to take a neutral stance or avoid slavery altogether, as the war went on they began to support emancipation and the recruitment of black troops. Visually, they traded highly caricatured depictions of African Americans for illustrations that praised the bravery and eagerness of the new troops.

The items below serve as a representative issue from each publication to give a sense of the illustrated press and how it morphed over the course of the war. In the issues seen here, Harper's Weekly covers the beginning of the war, the Southern Illustrated News the middle, and Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper the war’s end.