Anton Veenstra's Textile Blog

my textile career from 1975

Category Archives: textile, tapestry, heritage buttons

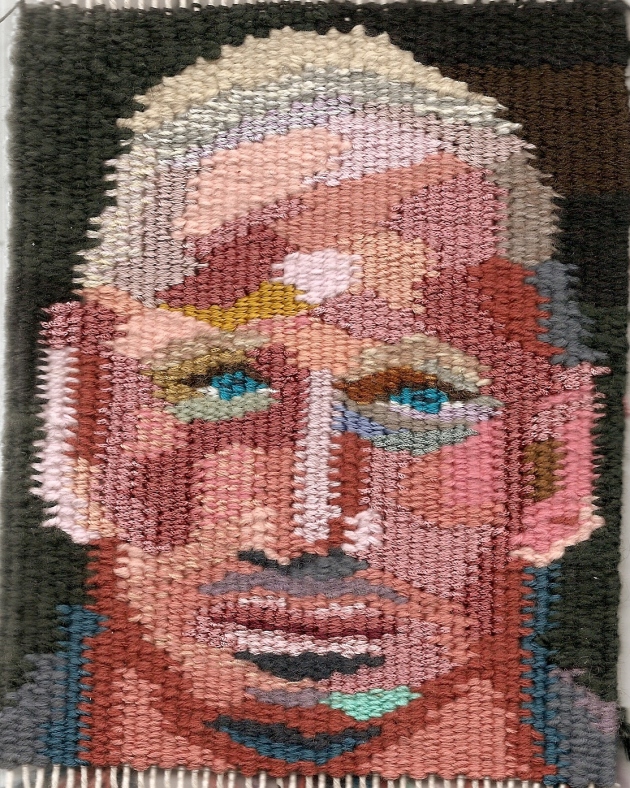

face of the times

A colleague on FB posted a bunch of photos of artwork from her travels around Europe. Among them were some really inspirational portraits from the Italian Renaissance. If you were a journo measuring business confidence you need look no further than the commissioned face artists put on the business community. That’s what the Medici family were doing by commissioning the artists of their time.

To take another tack momentarily, a senior artist in Sydney, Ken Unsworth, has a work on show at the Art Gallery of NSW; it’s a nest of river rocks, each wrapped three ways and suspended by three wires. To see the work is to marvel at, as he describes it, the inter-weaving of wires, that suspend the rocks. It’s a beautiful, serene work. I’m inspired, & find many points of similarity with my button work. But the historical lesson I would draw is that painters seem to have lost confidence in the potential of their medium; I can understand why. Modernism has made a series of violently new modes of expression available to us. After Cezanne, Van Gogh, Picasso, culminating in the Dutchman doing post-Abstract Expressionist portraits of the “American woman” in the USA, De Kooning, what’s left to do?

Post-Modernism at least allows us the choice of new materials, new protocols of working, new frames of reference. I’m used to old farts critiquing my work as NOT portraiture; the positive spin of which insight is that the gestures & mark-making necessary now looks thin and flat. After all those absinthe-soaked swirls of thick paint by Van Gogh, we need NEW & different, at least to honour the extremity of expression for which he gave his sanity and life.. My choice of combinations of two media: woven tapestry & button assemblage allows me this possibility; tapestry has a monumentality. It carries this as its DNA; you know just by looking at it, that the weaver has had to carry & juggle the design concept of the work non-stop through to the work’s completion; monumentality is how I would describe the impact. Button work is flat, yes textured, yes carrying mini-narratives. My balance of the flatness is to ensure that the buttons used carry a maximum wattage of light, diaphanous. Together, they have a unique impact.

The age we live in has achieved extraordinary greatness; it remains to be seen if collectively we, as a global culture, can survive our local pettiness, insularities, competitiveness, not to mention overpopulation, war, super viruses, global warming. If we survive & go forward, we need a better artform than just throwaway mass media imagery to reflect ourselves.

social commentary

Tapestry and social protest.

It was at university, during a first year English literature lecture that the concept of “universality” was explained. An author attempted to reach the widest audience, to do so he assumed a persona that you could easily relate to. What resulted was the cliche “a dead, white, middle class male”. By upbringing, I was anything but that; my mother had arrived in a strange southern land a European refugee and I had been born behind a wire fence. I grew up a “reffo kid”, classmates chanted “go back to where you came from” in the playground. I realised I was “ethnic” while they were ordinary. Later as I grew into my adult identity, I confronted societal homophobia, plus the effects of childhood abuse by a catholic pedophile priest. I recount this not for brownie points, but as things to confront in my art.

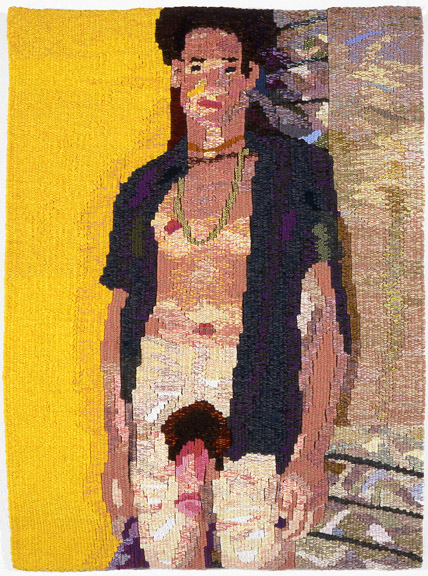

As a gay man invisibility was the reverse of universality; nowhere could I find my own kind, people who had gone before, clear accounts of their feelings, their needs, their struggles. We were all underground. However by the mid 1970’s, women were demanding equal rights, indigenous peoples struggled for a place, and migrants and refugees sought an identity. The mainstream male enjoyed beer and cricket, and thought about little else.

I settled on a textile medium, having written adolescent poetry for a decade, but found words a barrier to communication. The 1970’s was a decade when counterculture people were experimenting in all directions; the first tapestry I wove exuded a strong visceral impact; I was certain it could TELL A STORY. My earliest works were self portraits, and images of plants, birds and animals, in other words a mirror of my world with my reflection in a corner examining it all. Soon I began to create homoerotic images, not to shock outsiders, although that soon seemed inevitable, but to assert the qualities of the homintern, the gay brotherhood, gay liberation. As an example, when the Object Gallery produced the second Gay Mardi Gras show which included my work, Material Boys Unzipped in 1999, a critic remarked about the genital size of Odalisk, while a fellow craftsperson’s reaction to the work was that it contained exactly the right combination of joyous colour that a tapestry should have.

I began to realise that colour, texture and luminosity were the triangulation of my art practice; however, as all tapestry weavers will admit, there is one huge drawback to the medium. If the focus of your inspiration is a detail near the top of the cartoon, in other words, possibly six months of weaving away, the drudgery can grind away at the enthusiasm with which the work began. Often the will to complete it quickly dissipates and the work is abandoned. One solution I arrived at was experimenting with a different textile medium, that allowed the freedom painters had, to begin anywhere on the surface of the work. This was to create a mosaic which I called an “assemblage” of buttons sewn with upholsterer’s thread onto stretched canvas.

I had exhibited, in an expression of solidarity, during the annual Sydney Gay & Lesbian Mardi Gras, now an international event; people sometimes bought my work from those venues, but even feedback became sparse. I decided that mostly women collected textile work, and they had no desire to collect homoerotica. I decided on a new direction, enrolled at COFA the College of Fine Arts in Paddington, Sydney in 2000 to undertake my Master of Design Honours degree. My thesis would be my parents’ postwar migration and my own experience growing up in a migrant household. My birth in a detention camp, I felt, equipped me to understand the experience of successive waves of refugees to Australia: the Vietnamese in the 1970’s, Iraqis and Afghanis in recent years. Looking at my mother’s Slovenian folk culture, her country having been once part of the Ottoman empire, led to other insights. Visually, the Slovenian national flower, the mini carnation with fretted petals was also to be found depicted on the tilework of Turkish mosques and on their textiles.

This was a convenient link to Edward Said’s concept of “orientalism” and its recent manifestation in the wars between the west and Islamic culture. I assumed no particular stance in this area at first; I had travelled widely in the middle east in 1979: Egypt, Jordan, Syria and Turkey, as well as countries from which Islam had retreated: Greece, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria. I greatly admired the second generation of folk tapestries from Wissa Wassef, the Iranian carpet menders outside the El Azhar mosque in Cairo with their exquisite silk yarns, an opium-addicted worker sitting in the Han Halili souk, sewing appliqued buntings that decorated the streets in preparation for the visit of the Israeli President Begin.

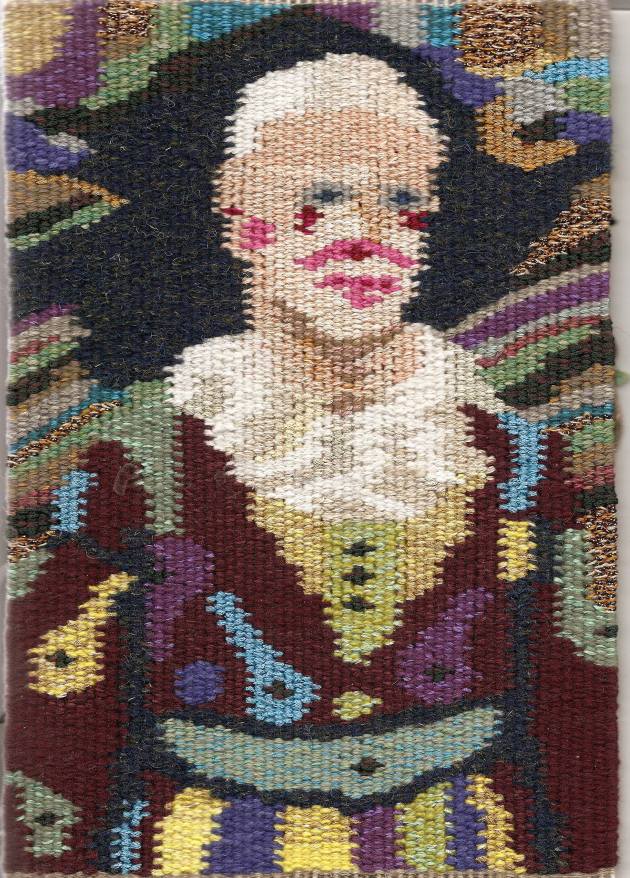

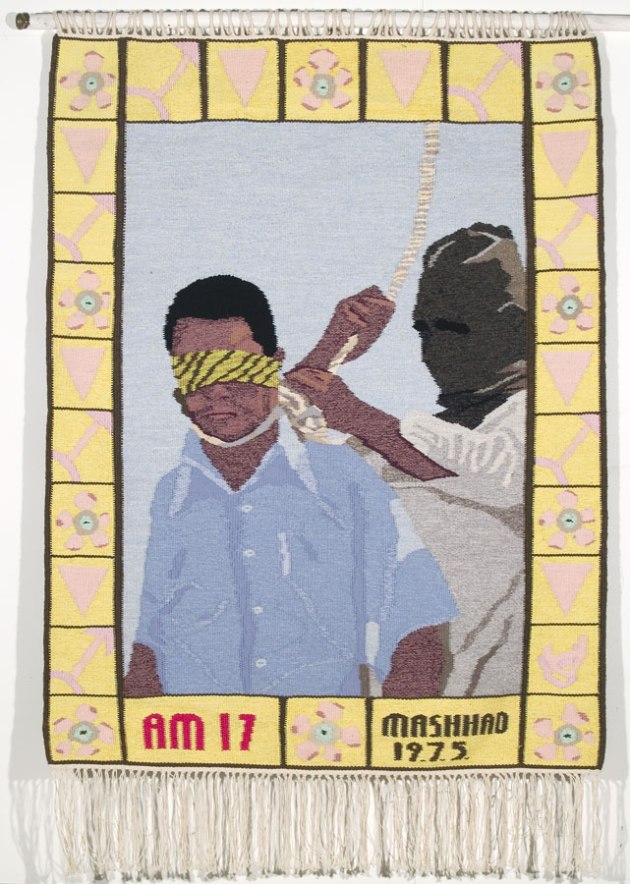

My protest came later, when I read of the honour killings and arrests of women and gay men by the “chastity police” of Iran, the foregone conclusion of sentencing by the Ayatollahs in the courts and the casual executions from cherry pickers in the market places of “religion cities” like Mashhad. I commemorated the execution of two youths on a carpet called the Hanging Garden. I have yet to come to terms with avid onlookers compulsively filming the event on their mobile phones. However, before we point the finger of indignation, it should be said that public execution was enjoyed as entertainment in the time of Queen Elizabeth 1. There, witches and sodomites were hanged or burned, the original meaning of the word “faggot” being a gay man wrapped in a bundle of sticks as fuel for the witch’s pyre. I personally feel that fundamentalism whether Abrahamic, catholic or other is a latter day version of the Inquisition, with suitably modern punishments like aversion therapy.

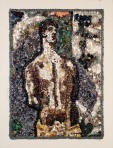

I remain determined to critique such babarities in my work; tapestry was once the triumphal celebration of the conqueror; now, it is capable of conveying the personal narrative of the marginalised. One of my recent tapestries is a portrait of a clown in a turn of last century English circus; I was determined to express the young man’s poise, his admirable dignity while dressed in colourful absurdity; I was intent on avoiding caricature. This continues my on-again off-again series of portraits, which includes two images of Gareth Thomas, a Welsh footballer who achieved national prominence, all the while struggling to come to terms with his homosexuality. They are simply head & shoulder shots which show the harmony of massive strength and inner peace. In this I have arrived at an understanding of a younger gay audience’s rejection of overt sexual imagery; perhaps the yet unresolved catastrophe of the Aids epidemic has played its part in this. I suspect it is a way a younger gay community is building links with wider communities on neutral grounds.

My impatience as a young weaver has disappeared with the maturity that time brings; the first step towards a solution had been to allow slits along adjacent vertical colour areas; these soon became unfortunate gaps once the work was cut from the loom. One day, while giving a talk at Newcastle University I saw the Swedish weaver Annika Eckdahl at work on a very large piece. Her technique was to use an interlocking join along adjacent vertical colour areas. Once a youthful impatience to weave quickly was overcome, it proved a satisfying method of creating shape, pattern and texture. In a Susan Maffei + Archie Brennan workshop in Sydney, the latter had admonished his class against weaving too quickly. After all, packing the weft around the row of warps involves the patient dance of the bobbin point, nothing else allows the yarn to sit flat on the surface. Textile artist Diana Wood Conroy has exhorted fellow weavers to make a virtue from what seems a chore; “Our work is a slow revolution”, she says.

Byline: Born to Dutch + Slovenian parents, I completed my Master of Design [Hons] degree at COFA in 2003. I contributed to socially critical art events: The Blake Prize for Religious Art [From Refugee to Citizen, the Compassionate Society] 2007; The New Social Commentary at Warnambool Gallery in 2006 [The Hanging Garden] and 2008 [Authorised to Instruct, a critique of catholic clerical pedophilia]. I weave tapestry and construct button assemblages or mosaics. For a more comprehensive examination of the above issues, please refer to my blog. http://antonveenstratextiles.com

form following function

BILLBOARD LED WHITEBOARD

My view of the agora is the busy urban square or piazza, a marketplace driven by commercial concerns. My work is a dialogue between the artisan and the industrial; in my urban scape the prototype is a black, found industrial object, displayed against a studio whiteboard, that becomes the inspiration for a billboard image, surrounded by led lights. For me, tapestry was the billboard imagery of previous eras. Here, its warp rows resemble the pixel lines of an electronic display.

My view of the agora is the busy urban square or piazza, a marketplace driven by commercial concerns. My work is a dialogue between the artisan and the industrial; in my urban scape the prototype is a black, found industrial object, displayed against a studio whiteboard, that becomes the inspiration for a billboard image, surrounded by led lights. For me, tapestry was the billboard imagery of previous eras. Here, its warp rows resemble the pixel lines of an electronic display.

Imaging and display are the means of persuasion used by market forces; every aspect is calculated and controlled. The media I employ in my combine are woven tapestry, button assembly and a found object. The modernism of the tapestry reappears in the column of street signs, an ancestral totemic pole of vintage buttons, minimal and faux-primitive. By employing several generations of buttons, my intention is to draw attention to their design development. I use pearlshell for its natural luminescence, compared to the surreal glow of the buttons framing the tapestry. The initial reaction of industrial technology was to imitate nature, then to create ever more startling effects of colour texture and luminosity.

My editor’s impulse was to provide a right bottom edge to the whiteboard, and also consolidate the columnar on the left vertical.

pointillist buttons

My catalogue of button assembly, comprising works of whimsy and the grand statements.

I want to compare and contrast the textures and techniques I’ve invented. Also my antecedents, from living with a couple of central Australian indigenous dot paintings by the community elder Clifford Possum Tjappaljari, to visiting the major exhibition of the French Nabi fauve painter Andre Derain, at the Art Gallery of NSW, where his amazing bridge paintings were collected in a room, and the show culminated in the Dance of Joy painting, that easily overshadowed the dance paintings of Matisse. Also my love of the impeccably realist but simultaneously intensely expressionist work of Van Gogh in Otterloo, Holland.

I need to examine the importance of patterned mark-making for me, perhaps an occasional sense that tapestry was unable to be a successful vehicle for this activity, which led me to explore the colour, texture and luminosity of buttons, their integrity and autonomous presence, greater even than wefts in tapestry, as each button sits alongside others but nevertheless presents its story, its origins. Its material origin becomes a deciding factor in how it manages to present colour, texture, luminosity: cellulose, bakelite, plastic or pearl-shell, each behaves differently.

button narrative

The Tamworth Textile Triennial has been dismantled, having clocked up a bigger attendance than any previous Tamworth Textile show. It is being packed up, and sent to the next destination, RMIT Melbourne in early Feb 2012. I am fine tuning my ideas for that show; it promises to be an event.

Tonight on SBS there was an ideas panel presented by Anton Enis looking at a very successful show SBS put together earlier in 2011 called Go Back to Where You Came From. It was about refugees and our, Australian reaction to them. There were focussed insights among the audience: one person described the Australian audience as multi-focal; many people argued that labelling people as “racist” was not useful. Another person said that some sections of Australian society considered themselves as “outside”; they never saw themselves represented on Australian TV. A young person working in the multi-cultural bureaucracy, and with digital media in mind, said that people being able to share their narrative was important.

Nobody simply asked whether so many refugees sewing their lips together indicated a successful govt policy. I am mulling over my own position and what I want to say. I’m sorry I did not interact with more people at the opening and next day, before my talk. Tho I know why, the effort of transplanting oneself by car over six hours of travel is exhausting, disconcerting, depleting, disorienting. I don’t drive, so my companion and driver took all of the physical burden. Nevertheless the journey took its toll.

Completing blog chapters on the two works exhibited was helpful, also the two jpgs of the work at an advanced stage then the severely revised version, with the stripped down fencing pattern, the re-highlit toy, proved an eye-opener. I was told that some curators still consider my craft somewhat of an outsider’s art object. That limited and retrograde viewpoint needs to be firmly binned.

But working with buttons has become a very sensitising process. Having taken the wrong turns in my Sailor Boy work, this has taught me to listen more carefully to the promptings of my intuition. The texture, colour and luminosity of buttons contributes so immensely to the final work. The autonomy of each unit contributes so much, period style, background, origin of manufacture add to the narrative.

As Dion Fortune said about another matter, the buttons teach me that there are no bad or wrong pieces; apt placement, context is all.

retro 2 my family

On the decade anniversary of my mother’s death, I decided to return to academia, to complete a studio based thesis on the migration of my family to Australia after World War 2 had ended. My mother had gone to work in Germany and was declared a displaced person when the fighting ceased. I used her ID photo taken by the International Refugee Organisation in my art work. My father was doubly orphaned in his preteens, he decided to enlist in the Dutch army and was shipped to Batavia to fight the insurrection. He was awarded the service medal, the star for order and peace, the ereteken voor orde en vrede.

My father was doubly orphaned in his preteens, he decided to enlist in the Dutch army and was shipped to Batavia to fight the insurrection. He was awarded the service medal, the star for order and peace, the ereteken voor orde en vrede.

The above works complete my family narrative with my parents’ transit from Bathurst through Cowra [where I was born] to Scheyville Migrant camp. We were then released, our status changed to that of citizens, dad found local employment, we lived in a stone house outside Pitt Town, on the bank of the Hawkesbury River. My immediate visual improvement was to acquire a sailor suit [in honour of the PopEye cartoon?]; this features in my two button works that follow.

Mum, 30 cms H X W, 2008.

Mum, Cowra, 80 cms H X 50 cms W, 2000.

Baby Photo, 30 cms H X W, 2008.

Scheyville, 60 cms H X 40 cms W, 2000.

Scheyville 2, 80 cms H X 60 cms W, 2007.

Dad, 75 cms H X 30 cms W, 2007.

retrospective 1 mardi gras themes

I’d like to present my work of the last 15 years or so. The following pieces are similar to what preceded, shown in 2 Sydney solo shows and 2 Mardi Gras themed shows at the Object Galleries at Customs House, Age of Consent 1999, reviewed by Bruce James in the Sydney Morning Herald, and Material Boys Unzipped 2000, which then toured nationally [Vic, Tas, Qld].![[adam] & steve](https://antonveenstratextiles.files.wordpress.com/2011/11/adam-steve.jpg?w=150&h=150)

[Adam] “& Steve”, uses a magnetic resonance image, the rib, to comment on fundamentalist based criticism of same sex unions. 30 cms H X W, 2006.

Desiring This, 2001, 95 cms H X W, [Desiring this man’s scope and that man’s art.]

Odalisk in the Object Galleries show Material Boys 2000, was reviewed by Ben Genocchio of the Australian, as a witty take on Ingres. 90 cms H X 60 cms W, 1999.

No country for old men, was my belated contribution to the Sydney Aids quilt project. I combined tapestry pieces, buttons, objects and print. 6 ft H X 3 ft W, 2008.

Harlequin, 2005 uses de-constructed Harris tweed yard, I dismembered a man’s jacket, bought in a vintage shop. Yes, its surface is hairy, it’s a bear of a work with a good heart. 45 cms H X W, 2005.

Manly Faery, 30 cms H X W, buttons and objects, quotes the 1980’s Australian Crawl song Reckless, As the Manly Ferry cuts its way to Circular Quay. Circular Quay as the historians will narrate, was the site of Capt Phillip’s landing inside Sydney Harbour. It is by default the culture precinct with the Museum of Contemporary Art and the fabulous House of White Sails, the Sydney Opera House. 30 cms H X W, 2007.

Dragon Bite, woven in 2002, entirely in the beautiful city of Ljubljana, capitol of my mother’s country of birth Slovenia. The dragon, emblem of the city, features as exquisite wrought iron detail on the bridge in the old city, designed by that amazing renaissance man Jose Plecnik. The fallen figure of course is a homage to El Greco’s Laocoon. 30 cms H X W, 2003.

Diver, 1982, was acquired by the Sydney Textile Museum as the 1983 annual award. It is based on the Bronski Beat song Small Town Boy. When it was shown at the Craft Australia Expo Sydney Centrepoint in 1983 it reminded an eastern European viewer of Lenin. She was unamused. 80 cms H X 50 cms W.

An unexhibited work, You Bloody Poofs R Awol, Snarls Sarge, is a flashback to cadet training at boarding school, dies ires, annus horribilis. We had gathered in the late afternoon, when our sarge noticed two school mates creep out of the bush, wearing broad cheeky grins. He interpreted their absence angrily. 95 cms H X W, 2007.

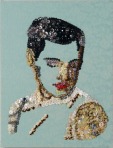

There is a beautiful photo of Elvis enlisting and being given an innoculation shot. His white tshirt is lifted to the shoulder, he looks fragile, delicate. 60 cms H X 40 cms W, 2007.

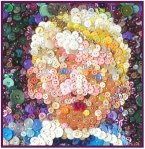

Michael Jackson, 30 cms H X W, 2008.

kiss my hand to the stars

Both Gerard Manley Hopkins and Walt Whitman influenced me as a late teenager. Whitman had an shambling ordinariness I could not hope to emulate; it takes great confidence to befriend suspicious straight guys. I don’t have the anaesthetic of voice or manner. Also an ABC radio dramatisation based on a phrase of Whitman’s, “bare-breasted knight”, gave his work an unreal spicy naughtiness. Hopkins was wreathed in his difficult language; I attempted to study him for the High School Certificate of 1967 but gave up. He was in a bracket with Percy Bysse Shelley and George Herbert, another “dry” difficult poet, with a similar need to be swept away by divine attention. Instead I opted for the group the rest of my class were plodding through: Donne, Wordsworth, Keats. When I gave up my solitary library study and returned to class to resume the uninterrupted dialogue with my English teacher I was welcomed back by relieved classmates.

But to read passages from Hopkins’ tour de force The Wreck of the Deutschland is to realise that Hopkins had taken up Keats’ challenge. The “mists of mellow fruitfulness” or even more cloying, from St Agnes’ Eve “tinct with cinnamon” becomes “a lush-kept plush-capped sloe”. Hopkins bypasses the sentimental deliberations; he is just as wrapt with the sensuosity of nature, but his language describes the experience with jerky astringent rhythms that took the English 50 years to appreciate. Then of course he had to be “translated” by that drunken swaggering, spiritual but not religious Welshman Dylan Thomas. But even Welsh musicality cannot match “the swoon of a heart that the sweep and the hurl of thee trod Hard down with a horror of height” or “I kiss my hand to the stars, lovely-asunder Starlight, wafting him out of it; and glow, glory in thunder”.

The words are rollicking, they deliberately swagger us out of a post-Shakespearean iambic pentameter, whose de dah de dah is insidious. Hopkins when he has freed us from singsong makes us appreciate a particularly tactile drywall of syllables. Stonework because Hopkins’ phrases in both sound and feel are made of nature; slices of organic naturalness comprise his work. Drywall because the mortar of accepted usage is absent, only the ear gives it balance. Even long after I had stopped writing poetry Hopkins’ massed slabs of words were palpable. I had only to move this sense of fitting forms together into a visual mode to explain the kinetic electricity of a lot of my gestural work. Take Attendant, for example. The atmospheric turbulence, like the gambolling of Chinese dragons, occurs beside the sitter’s ear and gives his poise an understory.

Later I transposed this need to arrange gestures into the scumble of button work.

Later I transposed this need to arrange gestures into the scumble of button work.

reffo kid

When my exhibition called Karantanija was advertised at the Marrickville Council run Chrissie Cotter Gallery in Pidcock Street Camperdown, the Slovenian reporter at SBS radio interviewed me. The word Karantanija is sacred to Slovenian hearts. In the year 639 a group of knights formed a round table administration of their Duchy. As a democracy it was not long lasting but sufficiently impressed the founding fathers of the USA that one of them on a fact-finding Grand Tour borrowed from their constitution.

I had just come back from my own Euro-exploration of Ljubljana, the capital, Bled and Murska Subota, my mother’s area of origin. I consulted the curators of the Slovene Ethnographic Museum and found in the foyer documentation of the design process for the flag of the newly declared Republic of Slovenia. It personally intrigued me, given the difficulty Australians experienced both in deciding on the shape of our nationhood and the details of the flag.

Though born in an internment camp for post World War Two refugees I feel privileged to be descended from two cultures, second and third tier sized compared with the UK, France and Germany, but both no-nonsense, entrepreneurial, rational and compassionate entities. My contribution to the mix is a new world Candide attitude.

I remember discovering the national parliament building in the centre of Ljubljana, its curious facade adorned with nude male gilded sculpture. I accosted the security guard at the entrance about viewing the proceedings. He was incredulous that I should want to do so; I asked him whether it contained the democratic process and wasn’t its essence the concept of being seen, being scrutinised, being critiqued.

When I broached this with the migrations curator at the Ethnographic Museum, we both remembered that under Tito’s socialist rule, citizens participated in the process of government both from their domestic and work situations. Your apartment building had a committee as well as your place of work. The curator thought that since democratisation, most people just wanted a breather from over-involvement, the space to be apathetic capitalists for awhile. Later in Sydney I met a current member of the Slovenian parliament; he was amused by the anecdote.