In this post, Steph takes an in-depth look at revenants; the troublesome undead who might get up to all manner of mischief and malevolent pastimes.

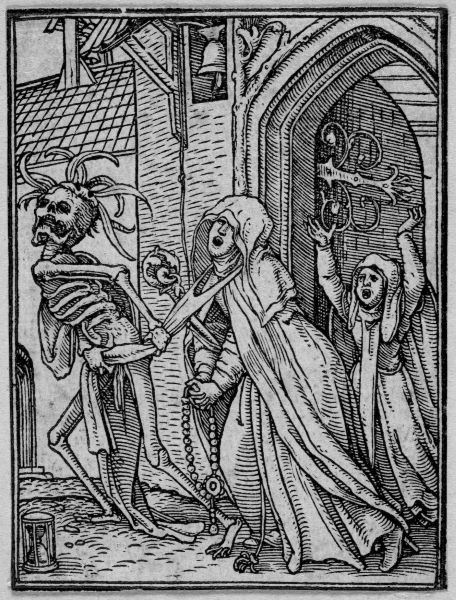

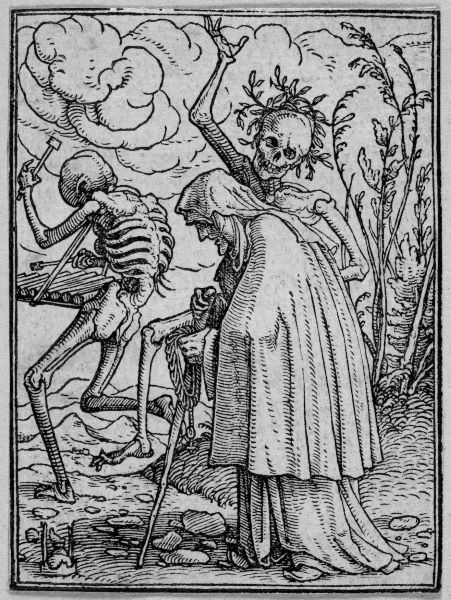

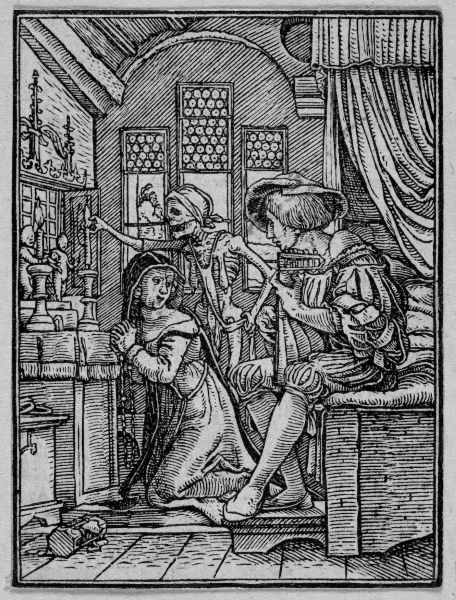

Here at the Whitworth we’re fortunate enough to have some woodcut prints credited to the blockcutter Hans Lützelberger. They’re from the Dance of Death series, a series consisting of forty-one woodcuts often attributed to Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/8–1543), for which Hans Lützelberger created some of the blocks. The prints show skeletal representations of death leading people from various walks of life to the end that ultimately awaits us all. Some of the skeletal figures seem to be quite mischievous, whereas others seem to border on cruel. Although the series has similarities with earlier works which fall into in the danse macabre genre, a popular genre during the late Middle Ages, this series of prints is more Early Modern than Medieval and no one is dancing here except Death.

Some of the living people in these prints are more accepting of their fate than others and others still are completely unaware of what is about to happen. The Abbess, who you’d think would be more prepared and perhaps even content to leave an earthly life behind, looks terrified. The danse macabre is a theme which reminds us that, regardless of your status in life, no one lives forever. But what about the dead who return? Although these prints do not depict revenants as such, they’re the closest thing we have to them in our collections. These comic yet sinister representations of death reminded me of some of the things people thought the undead got up to in parts of Europe during the Middle Ages, which I’d like to share with you today.

The Returned

During the Middle Ages the idea that the dead might return to visit the living was certainly present but not all folk beliefs were written down. A rather disturbing and perhaps one of the more well-documented examples of medieval beliefs in the dead coming back to trouble the living is the phenomena of the revenant.

The French ‘revenir‘ translates to ‘to come back/ return’. ‘Revenant’ can be used as a noun for ‘ghost’. The revenants of medieval folklore are usually a bit more substantial than our idea of ghosts. Revenants were often described as having physically left their graves, although they were not always visible to everyone at all times, and they might nearly crush people with their weight. Many were presented as reanimated corpses who physically interacted with the living and their spaces. To the men writing down accounts of revenants, such stories of the dead rising and walking again might confirm the Christian belief in the Resurrection.

Stories about revenants sometimes implied that they had been quite wicked in life, which perhaps left them open to corruption, or occasionally the wrath of a saint, even in death. Some accounts simply stated that the cause of the revenant problem was uncertain, even when their desciption of the revenant’s character paints a less than flattering picture. Sometimes a revenant was laid to rest close to or on a significant date for Christians, which may explain why some revenants were supposedly walking about without any explicit explanation as to what they had been like in life. Others were said to have died during horrible events which prevented them from being able to rest and, rather than being actively malevolent, merely acted as a warning to the living of their imminent death.

Although we might be tempted to make comparisons with zombies, the folklore presents revenants as having a bit more going on upstairs than your average zombie today. The figure of the zombie, according to some, originated in Haiti and today it is mostly portrayed as little more than a ravenous corpse, often both vector and victim of disease in popular culture. The gory, modern zombie is fairly removed from any links to the Transatlantic slave trade but is itself enslaved by the thing that drives it to chow down on former friends and family. Some revenants were seemingly possessed by spirits but, regardless of how they were reanimated, there’s often a sense that some sort of intelligence is still actively at play; something in the revenant is deliberately causing mischief, perhaps enjoying it even.

The Mischievous Undead?

What made revenants so monstrous if they didn’t try to feast on the living? They might knock on the dwellings of former neighbours and order them to come out or call them by name, before moving on to the next house in the worst game of knock-a-door-run ever. This sounds pretty mischievous but, although it may appear funny to us, there are some really sinister elements to these tales. Anyone a revenant decided to target in this way could become ill and die. Tales featuring revenants also indicate that some of them were believed to have a real propensity for violence and some were said to be the cause of outbreaks of disease that wiped out whole villages although, unlike zombies, they were not victims of the disease themselves. Other tales are both more humorous and bizarre. There are tales which feature a revenant catching their wife in the act of being unfaithful and one revenant seems to have been pretty happy to jump into bed with just about anyone in order to scare the life out of them!

Certain revenants are said to have been able to figure out the best way to harass their friends and family when particular options were closed off to them. According to William of Newburgh, writing in the 12th century, a man who died in Buckingham and was laid to rest ‘on the eve of the Lord’s Ascension’ rose the next night.[1] William says that the revenant climbed into bed with his wife, nearly crushing her with his tremendous weight. He subjected her to the same terrifying ordeal the next night and would have done the same again the night after but this time she was ready for him; she enlisted the help of others to guard her. Their shouting put him off trying to scare his wife again, so he made do with trying to scare his own brothers ‘in a similar manner’ but they, too, had surrounded themselves with neighbours.[2]

Realising he wasn’t going to inflict his mischief on humans at night, the revenant ‘rioted among the animals’.[3] He also started to bother the living during the day, when he was ‘visible only to a few’.[4] Eventually the revenant’s family and neighbours made the archdeacon aware of their problem, who in turn notified the Bishop of Lincoln. The bishop consulted with others, who claimed that such occurrences were not all that uncommon in England and suggested burning the revenant. This suggestion was unpalatable to the bishop, who instead produced a letter of absolution which was then placed on the revenant’s chest. After that, the revenant’s wanderings ceased.

Not all revenants played ghastly versions of juvenile games. Some revenants went to church! A tale recorded in the Chronicon Thietmari of the bishop Thietmar of Merseburg during the 11th century relates how a priest in Deventer was understandably horrified to discover the dead attending mass at night in a church which had fallen into disrepair. He sought advice from a bishop who, as the tale goes, wasn’t particularly helpful; the bishop instructed the priest to prevent the dead from entering the church. When the priest tried to follow the bishop’s order for the first time, the dead merely threw him out of the building.

Perhaps it wasn’t very Christian of them to lay hands on a man of God but they were clearly very intent on attending their version of mass. The bishop, when told about their response, repeated his orders. When the priest waited for the dead to appear in the church for a second time, it would be the last time he tried to stop them. The story goes that the dead noticed him hiding in the church and he met with a grisly end. No, they didn’t eat his brain! That’s not how the medieval undead roll. Instead they placed him on the altar and burned him. This tale contains echoes of Pre-Christian Slavic practices with regard to the idea of burning of something as an offering; historian Nancy Caciola notes that Thietmar himself also refers to older customs.[5] This brings up the question of just exactly how Christian these particular revenants are supposed to be; unlike the revenant William of Newburgh describes as being put to rest with a bishop’s letter of absolution, this ungodly congregation are impervious to the efforts of a man of God.

Some revenants had an ability to shapeshift. In one story related by Abbot Geoffrey of Burton Abbey during the 12th century, two men who invoked the wrath of Saint Modwenna died. They returned at dusk to a village where they had tried to stir up trouble against the Abbey the saint was interred in. Ocassonally they were seen carrying their coffins on their backs, at other times they walked as bears and other animals. Both an evil spirit and the saint they had offended were implicated as causes of their nightly wandering.

The Demise of the Undead?

So, apart from getting a letter of absolution from a bishop and placing it on the deceased’s chest, how could you tackle the problem of the walking dead?

Revenant folklore appears to have had a fair amount of similarities with the old folklore surrounding vampires before vampires had a sensual literary and on-screen makeover; vampires, like revenants, might try to crush or squeeze people as they slept and were said to cause epidemics. Some methods for getting rid of revenants are not too dissimilar to how people handled suspected vampires. Cutting off the head of a revenant, sometimes accompanied by other forms of dismemberment, could do the trick. So could removing the heart and burning the corpse.

Burials in which the deceased have been dismembered have been found in England dating back to before the Norman Conqest. A variety of explanations have been suggested for such treatment of the deceased in Anglo-Saxon deviant burials, some of which focus on the idea that people may have been trying to control or limit the power of the deceased in some way by actively trying to punish/ shame the deceased in death for any offences they may have committed or by trying to stop them from troubling the living. Some Anglo-Saxon deviant burials have been proposed by some scholars as evidence for old customs of the sort discussed in later revenant stories concerning beliefs in how to prevent the dead from rising. The explanations listed above are by no means the only explanations suggested for various kinds of deviant burials.

We may not recognise our monsters as being completely the same as the revenants of Medieval Europe but as societies and their religious beliefs change, so can some of their monsters. We can reimagine the undead to fit our own needs, although some of our anxieties have not changed much over the centuries. The undead never really died; during the 18th century, which we often think of as being a time for the death of superstition, there were stories of alleged vampires attacking the living in Europe and in 1762 the Cock Lane Ghost caused uproar in London. It was during the last years of 19th century that Bram Stoker gave us Dracula, who refuses to stay dead no matter how many times he has been staked through the heart. In the 1970s London became the imagined haunt of another, less distinguished, vampire; the press stirred up a frenzy over alleged sightings of the Highgate Vampire.

Given the popularity of various books, films and TV series; the undead are not going anywhere anytime soon. We’re still trying to vanquish our own version of the undead, too, albeit usually for recreational purposes; some paintball venues take their games up a notch by offering a zombie paintball experience. Today’s zombies also feature in popular video games, allowing you to hunt them from the comfort of your own home.

Footnotes

[1] Extract from William of Newburgh’s History of English Affairs in Scott G Bruce (editor), The Penguin Book of the Undead (New York, 2016), pp. 129-130.

[2] Extract from William of Newburgh’s History of English Affairs in Bruce (ed.), The Penguin Book of the Undead, p.130.

[3] Extract from William of Newburgh’s History of English Affairs in Bruce (ed.), The Penguin Book of the Undead, p.130.

[4] Extract from William of Newburgh’s History of English Affairs in Bruce (ed.), The Penguin Book of the Undead, p.130.

[5] Nancy Mandeville Caciola, ‘Revenants, Resurrection and Burnt Sacrifice’, Preternature: Critical and Historical Studies on the Preternatural, Vol 3, No 2, (2014), pp. 322-326.

Resources

http://gallerysearch.ds.man.ac.uk/Detail/1064

http://gallerysearch.ds.man.ac.uk/Detail/10566

http://gallerysearch.ds.man.ac.uk/Detail/2295

Historic England, News: New Archaeological Evidence Throws Light on Efforts to Resist “the Living Dead” in Medieval England. Published 3rd April 2017. https://historicengland.org.uk/whats-new/news/archaeological-evidence-living-dead-in-mediaeval-england/

Extract from Chronicon Thietmari in Scott G Bruce (editor), The Penguin Book of the Undead (New York, 2016), pp.119-121.

Extract from the writings of Abbot Geoffrey of Burton on the accounts of miracles attributed to Saint Modwenna, in Scott G Bruce (editor), The Penguin Book of the Undead (New York, 2016), pp. 122-126.

Extract from Walter Map’s treatise ‘On the Trifles of the Courtiers’ in Scott G Bruce (editor), The Penguin Book of the Undead (New York, 2016), pp.127.128.

Extract from William of Newburgh’s History of English Affairs in Scott G Bruce (editor), The Penguin Book of the Undead (New York, 2016), pp. 129-130.

Paul Barber, Vampires, Burial and Death: Folklore and Reality, Yale University Press (London, 1998).

Winston Black, ‘Animated corpses and bodies with power in the scholastic age’, in Joëlle Rollo-Koster (editor), Death in Medieval Europe: Death Scripted and Death Choreographed (London, 2017), pp. 71-92.

Sarah Juliet Lauro, The Transatlantic Zombie: Slavery, Rebellion and Living Death (London, 2015).

Nancy Mandeville Caciola, ‘Revenants, Resurrection and Burnt Sacrifice’, Preternature: Critical and Historical Studies on the Preternatural, Vol 3, No 2, (2014), pp. 311-338.

Nancy Mandeville Caciola, ‘’Night is conceded to the dead’: Revenant Congregations in the Middle Ages’, in Louise Nyholm Kallestrup and Raisa Maria Toivo (editors), Contesting Orthodoxy in Medieval and Early Modern Europe: Heresy, Magic and Witchcraft (London, 2017), pp.17-34.

Mike Mariani, ‘The Tragic, Forgotten History of Zombies’, The Atlantic (2015) [https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2015/10/how-america-erased-the-tragic-history-of-the-zombie/412264/]

Mark Hildebrandt, ‘Medieval Ghosts: the Stories of the Monk of Byland’, in Maria Fleischhack and Elmar Schenkel (editors), Ghosts- or the (Nearly) Invisible: Spectral Phenomena in Literature and the Media (2016), pp. 13-23.

Sarah Iles Johnson, ‘Many (Un) Happy Returns: Ancient Greek Concepts of a Return from Death and their Later Counterparts’, in Bradley N. Rice (author), Frederick S Tappenden (editor) and Carly Daniel Hughes (editor), Coming Back to Life: The Permeability of Past and Present, Mortality and Immortality, Death and Life in the Ancient Mediterranean, p.17-36.Montreal: McGill University Library, 2017. eBook. Accessed January 20, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvmx3k11.

Peter Parshall, ‘Hans Holbein’s “Pictures of Death”’, Studies in the History of Art (2001), Vol. 60, Symposium Papers XXXVII: Hans Holbein: Paintings, Prints and Reception (2001), pp. 82-95.

Andrew Reynolds, Anglo-Saxon Deviant Burial Customs (Oxford, 2009).

Charles West, ‘Revenants Revisited’, available on his Turbulent Priests blog [http://turbulentpriests.group.shef.ac.uk/revenants-revisited/], accessed January 19, 2021.

Zombie is a good term for describing the revenant. The word is much antique than the voodoo meaning, and is technically “walking corpse”. Some zombies of the African folklore were much similar to the european revenant, like the Nzambi and other corporeal ghosts. So, for me, revenants are zombies. In real life, they were people mistaken to be death and buried alive.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Megaraptor97! I did not know that! I’m definitely going to look into the Nzambi and other corporeal ghosts in African folklore now for a bit of light bedtime reading 🙂

LikeLike

It´s sad, because they never have gotten a big tread in mythology and folklore. Wikipedia mentioned them only a few times. Here are a picture of the creature. A monster who aproacches very close as a doppelganger of the Nzambi is the Baykok. It´s like the same myth. Only the fact that the Baykok is form the Objiwa tradition.

LikeLike

The modern zombie, like the revenant, can be consider a kind of vampire. Romero took the inspiration from I am Legend (Richard Matheson), and the legend of the Ghoul. That´s why the creature is complete non-zombie in the voodoo sense. The voodoo zombie never was a blood drinker, or flesh eater. The modern zombie is linked with the revenant, nachtzerer, craqueuhhe, gashadokuro, draugar, and many more undead corpses. The sentien zombies from Breathers and In the Flesh are much closer to the revenant. The frontiers were broken, and now new kinds of living dead will rise in the mass media.

LikeLike