As many readers are aware, I spend a lot of time (too much time?) thinking about arboreal alligator lizards in the genus Abronia. These squamates are fascinating for a litany of reasons. They are physically striking animals, they possess an air of mystery due to their secretive tree-dwelling behavior, and they live in remote, inaccessible “sky islands” of habitat. We have much to learn, and this makes them an exciting group to study.

A sampler of Mexican species of Abronia From top: A. bogerti, A. taeniata, and A. graminea.

The 29 described species of Abronia are also emerging conservation flagships for imperiled Mesoamerican cloud forests. Most major mountain ranges between central Mexico and western Honduras support their own unique, range-restricted Abronia. Some species, in fact, are known to science from just a single cloud forest peak. Allopatric speciation is thus considered the dominant pattern in their evolutionary radiation—in any given forest, on any given mountain, you’ll find just one Abronia species.

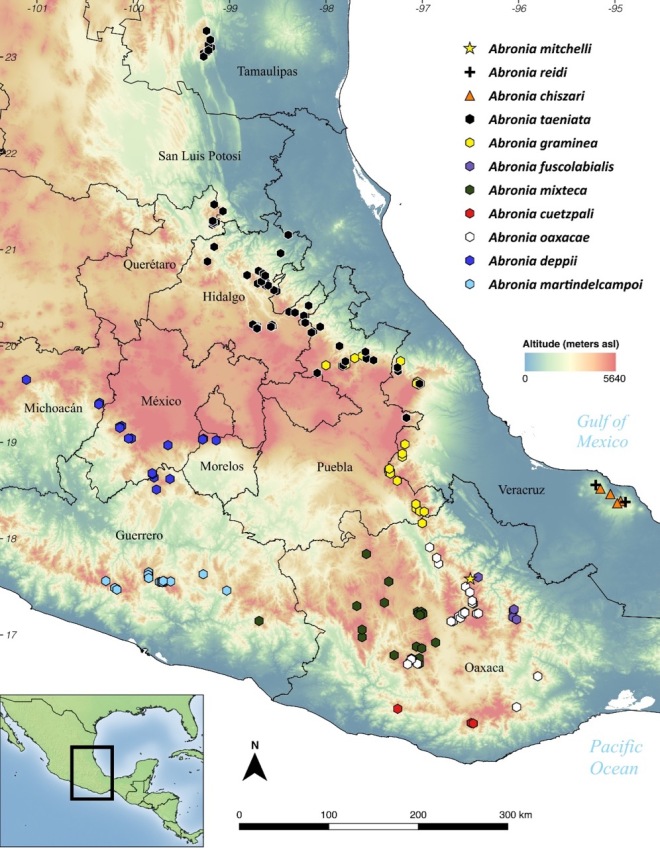

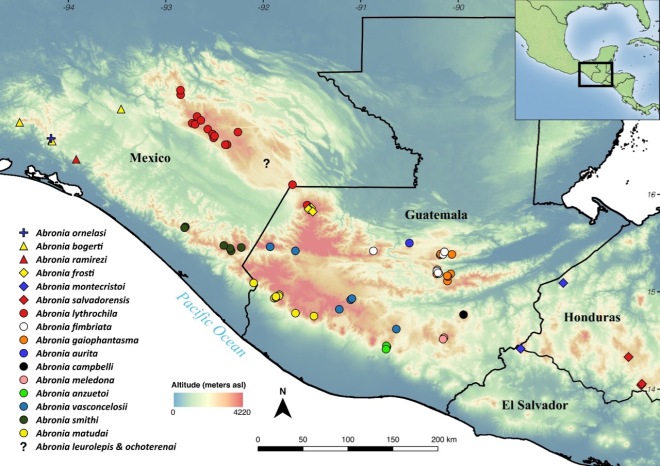

Or at least, that was the conventional wisdom until recently. Things are changing. The acquisition of new field data has taught us that about one-third of Abronia actually occur in sympatry with a congener. The maps below provide a big-picture overview.

But let’s explore what’s happening in these maps more closely. In eastern Mexico’s Sierra Madre Oriental, there is a 100-km zone of sympatry between A. graminea and A. taeniata. Reduced morphological differentiation in this zone, together with ongoing genetic work, suggests the possibility of gene flow; conversely, one or both taxa might harbor as-yet unidentified cryptic species-level lineages—the exact story remains unclear. Farther to the south in the Mexican state of Oaxaca, there are remarkable reports of A. mixteca and A. oaxacae (or at least, animals morphologically consistent with those two species) being found on the same tree. Elsewhere in Mexico, on opposite sides of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, members of the Scopaeabronia clade are paired with members of the Abaculabronia clade. Available records indicate that the two largest volcanoes in Los Tuxtlas support both A. chiszari and A. reidi, and that Cerro Baúl in the Chimalapas highlands supports both A. bogerti and A. ornelasi in overlapping elevation bands. Turning to Guatemala, recent sampling has shown that the distantly-related A. frosti and A. lythrochila occur within 5 km of each other on the same flank of the Sierra de Los Cuchumatanes. Farther to the east, a 50-km arc of Guatemala’s Sierra de Xucaneb mountains is occupied by populations of both A. fimbriata and A. gaiophantasma. Suspected, but as-yet unconfirmed sympatry may also exist between A. fuscolabialis/A. mitchelli and A. cuetzpali/A. oaxacae in different regions of Oaxaca, Mexico.

Now hold on a minute, you might be saying. Sympatry is one thing. But what about syntopy, where multiple species occupy the exact same spot (in this case, the exact same trees)?

The answer is that out of the six confirmed sympatric species pairs, syntopy has actually only been documented in two: A. mixteca/A. oaxacae and A. fimbriata/A. gaiophantasma. So, many sympatric Abronia might still plausibly be considered niche-segregated, due to the heterogeneous forest mosaic on Mesoamerican mountains. Countering that argument, however, is growing evidence that individual Abronia species can inhabit a wider range of elevations and forest microhabitats than previously believed. For instance, in the past two years A. taeniata has been found at the bizarrely low elevations of 125 and 300 m in Hidalgo, Mexico. These and other observations emphasize that slope, aspect, soil composition, and prevailing moisture-bearing winds all combine to create a wondrously complex patchwork of montane forest niches. Elevation alone can’t explain things perfectly. Coupled with field sampling difficulties, this situation continues to challenge efforts to draw accurate, fine-scale conclusions about where Abronia exist on the landscape.

Suffice it to say, the biogeographic story of Abronia evolutionary diversification and habitat occupancy has become a lot more problematic lately. Nonetheless, we can apply these lessons to help resolve, or at least draw attention to, some troublesome taxonomic situations in the Abronia Tree of Life. Stay tuned for an upcoming post exploring one such case.

You and I have talked briefly about this before, but the graminea/taeniata situation makes me wonder about the possibility of gene flow. Are they supposed to be sister taxa? How diagnosable are they with respect to one another?

We’d love to get feedback from anyone with experience with these lizards. The variation in dorsal coloration is wild!

LikeLike

Great questions! Some colleagues and I reviewed the taxonomic history of these two species, and analyzed their morphology across the zone of sympatry, in a recent paper available here: http://www.herpconbio.org/Volume_13/Issue_1/Clause_etal_2018.pdf.

The short answers are:

(1) Yes, they are likely sister taxa

(2) They are not easily diagnosable in the zone of sympatry, but are much more diagnosable elsewhere in their geographic range.

I do not have the genetic data, and so cannot speak to to the possibility of gene flow with any authority. But I know that it is being worked on.

As with most Abronia, we are in desperate need of more physical samples, without which we cannot rigorously answer these or other questions. But samples are slow to accumulate. I’ll reiterate one of the central messages of our paper…please, please, please collect a physical sample (when permits allow) of any Abronia that you might encounter at a novel locality.

LikeLike

Sounds like it could be a cool hybridization/admixture study! Reminds me a little of the weirdness in the Sceloporus formosus group in Mexico (which also needs attention).

LikeLike

Not to mention the weirdness in the S. torquatus group (e.g., S. minor – polychromatism aside, seems there is some polymorphism in dorsal scalation between pop’s from different regions). Work continues on the formosus group, yes?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very cool read. Anxious for more Abronia developments. Thanks for these great maps, AGC!

LikeLike

Thank you, Jackson!

LikeLike