THE MONOTONY OF DARBY CRASHISM

by Chris R. Morgan

The first show the Germs played was at Hollywood’s Orpheum Theater in April of 1977. They were to open for the nascent Weirdoes, who picked the Germs because they were even more nascent, having only just formed that month with no rehearsals, no songs, and no knowledge of their instruments. Their set lasted 10 minutes before they were removed from the stage. The band, with guitarist Pat Smear, bassist Lorna Doom, and drummer Donna Rhia, blared feedback at the audience (which included The Damned) while singer Darby Crash wrapped himself in licorice whips, that soon melted, and slathered himself in salad dressing and peanut butter on top of that. For a later show, the band would tell their friends to bring food of their own; during a rendition of The Archies’ “Sugar, Sugar,” they poured bags of sugar on the audience.

In every regional scene one was likely to know at least one band purely by reputation. Even if its members were not the most proficient musicians, and their songs were rudimentary at best, their shows were not to be missed. They were more social experiment or life sculpture than musical act, demolishing the invisible wall between spectator and spectacle, along with actual walls. Seattle had The Mentors (among others), San Francisco had Flipper, Detroit had The Meatmen, Austin had Scratch Acid (among others), and DC had No Trend. One band for my cohort was The Ultimate Warriors, from Nazareth, PA. When they played our town’s recreation center in 2000, they (or their entourage) donned luchador costumes and other wrestling-themed gear and wreaked havoc in the pit. I believe they also brought fruit as the venue smelled of bananas after they played. They are now Pissed Jeans.

Within this ilk the Germs were very much among their number, even their ancestor. Even at their best they never played technically well. Slash writer Claude Bessy described their debut single “Forming” as “beyond music … inexplicably brilliant in bringing monotony to new heights.” But at the same time, the Germs were able to shake off their “joke band” status, in part because getting constantly banned from venues was a net negative, but also because something more powerful was at hand. By September 1977, the Germs were headlining shows with massive turnouts. As Geza X recalled later, “it was the buzz on the Germs as a social force more than a musical one that caused a line to form outside The Masque for the first time.”

Darby Crash (née Bobby Pyn, née Jan Paul Beahm)[1] was born and raised in the Los Angeles area. His childhood was one of routine instability. He lost a brother to a heroin overdose. His mother struggled with minimum wage jobs, often working nights. The closest thing he had to a father figure was a stepfather who died when he was 13. His education, which he neglected, included an experimental program that combined Werner Erhard’s est with Scientology. Darby was precocious, however, with his mother carving out sections of her stringent budget to appease his voracious intellectual appetite with books and a typewriter. He developed interests in Nietzsche, Charles Manson, Herman Hesse, Hitler, and Oswald Spengler. Typical interviews included the following: “Fascism is not a philosophy. It’s a way of life. Fascist is totally extreme right. We’re not extreme right. Maybe there’s a better word for it that I haven’t found yet, but I’m still going to have complete control.” And: “I can respect Hitler for being a genius in doing what he did, but not for killing off innocent people. [His genius] lies in his speech. What he could do with words.”

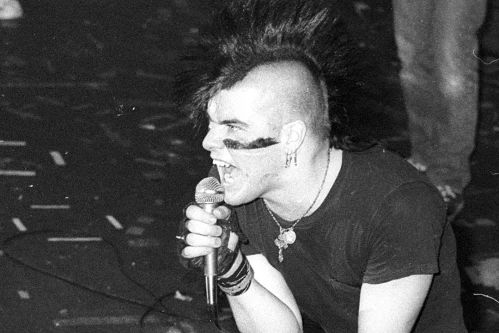

Darby Crash’s vocal style relied on barely annunciated snarls and screeches. Perhaps you’d rather not imagine a cat being processed by a wood chipper, but that is the image conjured for me whenever I hear him. Yet the words were there. Indeed, the quality of Darby’s lyrics was a surprise even to those who liked the band. “Standing in the line we’re aberrations/Defects in a defect’s mirror/And we’ve been here all the time real fixations/Hidden deep in the furor,” goes the first verse of “What We Do is Secret.” But so, too, was the personal charisma to which chaos and music alike were subsumed.

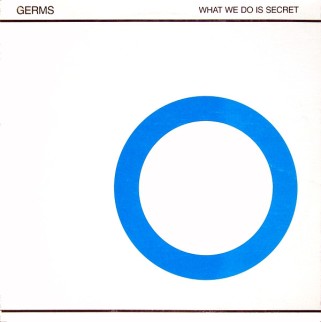

“I completely control a number of people’s lives,” Darby Crash said. “Look around for the little girls wearing CRASH TRASH T-shirts and people like that.” Darby had a gift for branding. In a way, the Germs became a serious enterprise for him not with the refinement of their artistry but with the aesthetic identity he crafted around it. “Everything works in circles,” he said. “[L]ike something you’ve done maybe eight years ago, but all of a sudden it feels like you’re in the same place doing the exact same thing.” They adopted as a symbol of a clean blue circle, to match Darby’s eye color, which appeared on their merchandise, flyers, and recordings. Germs fans were collectively called “Circle One,” who wore “Germs burns” on their wrists, which came from a cigarette. “I think we should make a new shape for flags. Round flags.”

Darby’s proposals did not stop there. He dreamed of putting “allies in key positions,” in such places as the postal service and newspaper presses who, with little more than flicking a rubber band, could jam the gears of society and bring it to its knees. When appearing on a radio show, Darby rang off a series of satellite numbers that would allow anyone to make long distance calls for free. He became obsessed with L. Ron Hubbard and, according to the Screamers’ K.K. Barrett, “talked about how religion was just basically a funnel for lost souls.” “Darby Crash completely resocialized me,” F-Word singer Rik L. Rik recalled. “He taught me to question everything and how to make up my own mind by evaluating reality and drawing my own conclusions. … He did this for everybody he came in contact with. It was a whole retraining program.”

Darby’s proposals did not stop there. He dreamed of putting “allies in key positions,” in such places as the postal service and newspaper presses who, with little more than flicking a rubber band, could jam the gears of society and bring it to its knees. When appearing on a radio show, Darby rang off a series of satellite numbers that would allow anyone to make long distance calls for free. He became obsessed with L. Ron Hubbard and, according to the Screamers’ K.K. Barrett, “talked about how religion was just basically a funnel for lost souls.” “Darby Crash completely resocialized me,” F-Word singer Rik L. Rik recalled. “He taught me to question everything and how to make up my own mind by evaluating reality and drawing my own conclusions. … He did this for everybody he came in contact with. It was a whole retraining program.”

These ambitions were quickly derailed; first by Darby’s abrupt sabbatical in London, which broke up the band, and then by his death at age 22 by intentional heroin overdose once he returned. It is on this morbid crux that Darby’s legacy is balanced. As he’d often voice his intention of dying young, sometimes at the exact age when he did, I can’t say it is altogether unfair—but it is also too simple.

Darby returned from London in 1980 sporting a Mohawk haircut and face paint. He’d met and become enamored with Adam and the Ants, much to the bewilderment of his friends. Indeed, when Adam and the Ants were doing an in-store appearance at Tower Records around the same time, Black Flag disrupted the proceedings, throwing around their trademark flyers reading “BLACK FLAG KILLS ANTS ON CONTACT.” The Hermosa Beach-based band formed a year before the Germs, and promoted a stripped-down version of punk that favored brutality over—or rather, in addition to—chaos. The Hollywood scene did not appreciate it as it attracted a more aggressive police response and repelled their female fan base. But like Darby Crash, Black Flag’s Greg Ginn had his own ambitions, involving hours-long daily practices, endless touring, and sustaining his own record label. Darby never even held a job. Ginn’s efforts helped make hardcore a national concern, eclipsing the more nuanced Hollywood scene. Ultimately the flag shape was to be deconstructed rather than changed outright.

Whether longevity was ever a possibility for the Germs, its undesirability is less arguable. Darby Crash was a genius. He was among the first to understand that this youth phenomenon was more than a temporal market demographic. He understood that its adherents’ idealism and energy could be concentrated into an overwhelming counterattack against the predominant culture, so long, of course, as their cry came from his voice. “Whatever it is people like that have in them that enables them to attract a following, he had it in him,” Pat Smear said. “I’m talking about some guy coming from a log cabin and ending up being president of the USA.” Darby Crash was the earliest, and perhaps the only, self-made cult of personality in punk, at least the cult that was focused on an individual. His vision of punk was ceremonial, historical, and abstract, but it was not ethical.

Not that Darby Crash should be forgotten. He was too right and too wrong in equal measure to be damned either to obscurity or infamy. And the path he chose made his gifts too evident after more than half a lifetime of deprivation. Whether or not punk’s more ethical turn was the correct one is a debate that may never be settled. Nor should it be, for punk is in all respects a movement against monotony. It is also a movement that, having embraced Darby Crash’s world-historic call to greatness, was quite efficient in finding it disappointing at best. Punks have travelled too many shapeless roads and found too many permutations of themselves along the way to abide by the dull logic of a circle.

1 For background of this piece, I am indebted to this article, these books, and the liner notes to this album.